French language

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Languages

| French français |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | IPA: [fʁɑ̃sɛ] | |

| Spoken in: | France, Switzerland,Canada,Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco, Morocco, Algeria,Tunisia, Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Niger, Senegal, Haiti, Lebanon, Martinique, Vietnam, Central Africa, Tchad, Madagascar, Cameroun, Gabon, and other countries. | |

| Region: | Africa, Europe, Americas, Pacific | |

| Total speakers: | 128 million native or fluent | |

| Ranking: | 9 | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Italic Romance Italo-Western Western Gallo-Iberian Gallo-Romance Gallo-Rhaetian Oïl French |

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language of: | 30 countries | |

| Regulated by: | Académie française (France) Office québécois de la langue française (Quebec, Canada) | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | fr | |

| ISO 639-2: | fre (B) | fra (T) |

| ISO/FDIS 639-3: | fra | |

|

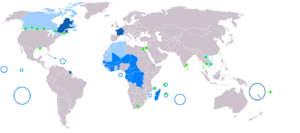

Dark blue: French-speaking; blue: official language; Light blue: language of culture; green: minority |

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. See IPA chart for English for an English-based pronunciation key. | ||

French is a Romance language spoken originally in France, Belgium, and Switzerland, and today by about 130 million people around the world as a mother tongue or fluent second language, with significant populations in 54 countries.

Descended from the Latin of the Roman Empire, its development was influenced by the native Celtic languages of Roman Gaul (particularly in pronunciation), and by the Germanic language of the post-Roman Frankish invaders. It has borrowed substantial amounts of vocabulary as well, historically from Ancient Greek in particular.

It is an official language in 41 countries, most of which form what is called in French La Francophonie, the community of French-speaking nations.

From the 18th century well into the 20th century, French was the leading international language of culture and diplomacy, and knowledge of French was considered a requirement for better-educated classes around the world as late as the 1970s. Due to this legacy -- and ongoing strenuous efforts by the French government -- it retains significant use today in international affairs despite its replacement by English as the "world language".

It is an official or administrative language of the African Union, the European Broadcasting Union, ESA, the European Union, FIA, FIFA, FINA, IHO, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, the International Court of Justice, the International Olympic Committee, the International Political Science Association, the International Secretariat for Water, Interpol, NATO, the UCI, the United Nations and all its agencies (including the Universal Postal Union), the World Anti-Doping Agency, and the World Trade Organization.

Geographic distribution

Legal status in France

Per the Constitution of France, French has been the official language since 1992 (although previous legal text have made it official since 1539, see ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts). France mandates the use of French in official government publications, public education outside of specific cases (though these dispositions are often ignored) and legal contracts; advertisements must bear a translation of foreign words.

Contrary to a common misunderstanding both in the American and British media, France does not prohibit the use of foreign words in websites nor in any other private publication, as that would violate the constitutional right of freedom of speech. The misunderstanding may have arisen from a similar prohibition in the Canadian province of Quebec which made strict application of the Charter of the French Language between 1977 and 1993, although these regulations addressed language used in advertising and the provision of commercial services offered within the province, not the language of private communication.

In addition to French, there are also a variety of languages spoken by minorities, though France has not signed the European Charter for Regional Languages yet.

Legal status in Canada

About 5.2% of the world's francophones are Canadian, and French is one of Canada's two official languages (the other being English). Various provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms deal with Canadians' right to access services in both languages. By law, the federal government must operate and provide services in both English and French, proceedings of the Parliament of Canada must be translated into both these languages, and all Canadian products must have bilingual labels. Overall, about 13% of Canadians have knowledge of French only, while 18% have knowledge of both English and French.

In contrast, over 80% of the population of Quebec speaks French (the largest French-speaking city besides Paris is Montréal). It has been the sole official language of Québec since 1974; this was reiterated in law with the 1977 adoption of the Charter of the French Language (popularly referred to as Bill 101), which guarantees that every person has a right to have the civil administration, the health and social services, corporations, and enterprises in Quebec communicate with him in French. Although some arrangements of the Charter allow the use of English in order to respect the freedoms and rights of Québec's anglophone minority (such as access to health and social services), French is widely promoted.

The provision of Bill 101 that has arguably had the most significant impact mandates French-language education unless a child's parents or siblings have received the majority of their own education in English within Canada. This measure has reversed a historical trend whereby a large number of immigrant children were sent to English schools. In so doing, Bill 101 has greatly contributed to the "visage français" (French face) of Montreal in spite of its growing immigrant population. Other provisions of Bill 101 have been ruled unconstitutional over the years, including those mandating French-only commercial signs, court proceedings, and debates in the legislature. Though none of these provisions are still in effect today, some continued to be on the books for a time even after courts had ruled them unconstitutional as a result of the government's decision to invoke the so-called notwithstanding clause of the Canadian constitution to override constitutional requirements. In 1993, the Charter was rewritten to allow signage in other languages so long as French was markedly "predominant."

The only other province that recognizes French as an official language is New Brunswick, which is officially bilingual like the nation as a whole. Outside of Québec, the highest number of francophones in North America reside in Ontario, whereas New Brunswick, home to the Acadians, has the highest percentage of francophones after Quebec. In Ontario, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Manitoba, French does not have full official status, although the provincial governments do provide full French-language services in all communities where significant numbers of francophones live. Canada's three northern territories ( Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut) all recognize French as an official language as well.

All provinces make some effort to accommodate the needs of their francophone citizens, although the level and quality of French-language service varies significantly from province to province. The Ontario French Language Services Act, adopted in 1986, guarantees French language services in that province where the francophone population exceeds 5% of the total population; this has the most effect in the north and east of the province, as well as in other larger centres such as Ottawa, Toronto, Hamilton, Mississauga, London, Kitchener, St. Catharines, Greater Sudbury and Windsor. However, the French Language Services Act does not confer the status of "official bilingualism" on these cities, as that designation carries with it implications which go beyond the provision of services in both languages. The City of Ottawa's language policy (by-law 2001-170) has two criteria which would allow employees to work in the language of choice and be supervised in the language of choice; this policy is being challenged by an organization called Canadians for Language Fairness. A law similar to the Ontario French Language Services Act came into effect in Nova Scotia in 2004.

Canada has the status of member state in the Francophonie, while the provinces of Québec and New Brunswick are recognized as participating governments. Ontario is currently seeking to become a full member on its own.

Other nations

French is an official language in Switzerland. It is spoken in the part of Switzerland called Romandie. In Belgium, it is the official language of the Walloon Region (excluding the East Cantons, which are German-speaking) and one of the two official languages of the capital, Brussels, along with Dutch. Officially Dutch and French have parity in Brussels. However, in practice the French language is more dominant among the city's residents. Conversely the Dutch language dominates among the city's largely non-resident (in Brussels) workforce. It should be noted that French is not an official language or even a recognised minority language in Flanders, although there are some districts in Belgium along linguistic borders that have special compromise linguistic regimes. It is one of the official languages in Luxembourg, along with German and Luxembourgish. It is also an official language, along with Italian, in Valle d'Aosta, Italy. It is the official language of the principality of Monaco and is spoken by a small minority in the principality of Andorra.

In the Americas, French is an official language of Haiti, although it is mostly spoken by the upperclass and well educated while Haitian Creole is more widely used. French is also the official language in France's overseas territories of French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Barthelemy, St. Martin, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. It is also an administrative language of Dominica and the U.S. states of Louisiana and Maine.

French is an official language of many African countries, many of them former French or Belgian colonies:

- Benin

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cameroon

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Comoros

- Congo (Brazzaville)

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Djibouti

- Equatorial Guinea (former colony of Spain)

- Gabon

- Guinea

- Madagascar

- Mali

- Mauritius

- Niger

- Rwanda

- Senegal

- Seychelles

- Togo

In addition, French is an administrative language of Mauritania and is commonly understood (though not official) in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia.

In Asia, French is an administrative language in Laos and Lebanon, and is used unofficially in parts of Cambodia, India ( Pondicherry, Mahé, Karikal and Yanam), Syria and Vietnam. But, French has official language status in Union Territory of Pondicherry along with the region's de facto Language Tamil.It is an official language in the French territories of Mayotte and Réunion both located in the Indian Ocean.

French is also an official language of the Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu, along with France's territories of French Polynesia, Wallis & Futuna and New Caledonia.

Regional varieties

- Acadian French

- African French

- Aostan French

- Belgian French

- Cajun French

- Canadian French

- Cambodian French

- Guyana French (see French Guiana)

- Indian French

- Jersey Legal French

- Lao French

- Levantine French

- Maghreb French (see also North African French)

- Meridional French

- Metropolitan French

- New Caledonian French

- Newfoundland French

- North American French

- Oceanic French

- Quebec French

- South East Asian French

- Swiss French

- Vietnamese French

- West Indian French

Derived languages

- Antillean Creole

- Chiac

- Haitian Creole

- Lanc-Patuá

- Mauritian Creole

- Michif

- Louisiana Creole French

- Réunionese Creole

- Seychellois Creole

- Tay Boi

History

Sound system

Although there are many French regional accents, only one version of the language is normally chosen as a model for foreign learners. This is the educated standard variety of Paris, which has no commonly used special name, but has been termed "français neutre".

- Voiced stops (i.e. /b d g/) are typically produced fully voiced throughout.

- Voiceless stops (i.e. /p t k/) are described as unaspirated; when preceding high vowels, they are often followed by a short period of aspiration and/or frication. They are never glottalised. They can be unreleased utterance-finally.

- Nasals: The velar nasal /ŋ/ occurs only in final position in borrowed (usually English) words: parking, camping, swing. The palatal nasal can occur in word initial position (e.g. gnon), but it is most frequently found in intervocalic, onset position or word-finally (e.g. montagne).

- Fricatives: French has three pairs of homorganic fricatives distinguished by voicing, i.e. labiodental /f/–/v/, dental /s/–/z/, and palato-alveolar /ʃ/–/ʒ/. Notice that /s/–/z/ are dental, like the plosives /t/–/d/, and the nasal /n/.

- French has one rhotic whose pronunciation varies considerably among speakers and phonetic contexts. In general it is described as a voiced uvular fricative as in “roue” wheel [ʁu]. Vowels are often lengthened before this segment. It can be reduced to an approximant, particularly in final position (e.g. “fort”) or reduced to zero in some word-final positions. For other speakers, a uvular trill is also fairly common, and an apical trill [r] occurs in some dialects.

- Lateral and central approximants: The lateral approximant /l/ is unvelarized in both onset (“lire”) and coda position (“il”). In the onset, the central approximants [w], [ɥ], and [j] each correspond to a high vowel, /u/, /y/, and /i/ respectively. There are a few minimal pairs where the approximant and corresponding vowel contrast, but there are also many cases where they are in free variation. Contrasts between /j/ and /i/ occur in final position as in /abɛj/ abeille “bee” vs. /abɛi/ abbaye “monastery”, “abbey”.

French pronunciation follows strict rules based on spelling, but French spelling is often based more on history than phonology. The rules for pronunciation vary between dialects, but the standard rules are:

- final consonants: Final single consonants, in particular s, x, z, t, d, n and m, are normally silent. (The final letters 'c', 'r', 'f', and 'l' however are normally pronounced.)

-

- When the following word begins with a vowel, though, a silent consonant may once again be pronounced, to provide a liaison or "link" between the two words. Some liaisons are mandatory, for example the s in les amants or vous avez; some are optional, depending on dialect and register, for example the first s in deux cents euros or euros irlandais; and some are forbidden, for example the s in beaucoup d'hommes aiment. The t of et is never pronounced and the silent final consonant of a noun is only pronounced in the plural and in set phrases like pied-à-terre.

- Doubling a final 'n' and adding a silent e at the end of a word (e.g. Parisien → Parisienne) makes it clearly pronounced. Doubling a final 'l' and adding a silent 'e' (e.g. "gentil" -> "gentille") adds an [j] sound.

- elision or vowel dropping: Some monosyllabic function words ending in a or e, such as je and que, drop their final vowel when placed before a word that begins with a vowel sound (thus avoiding a hiatus). The missing vowel is replaced by an apostrophe. (e.g. je ai is instead pronounced and spelt → j'ai). This gives for example the same pronunciation for "l'homme qu'il a vu" ("the man whom he saw") and "l'homme qui l'a vu" ("the man who saw him").

Orthography

- nasal " n" and " m". When "n" or "m" follows a vowel or diphthong, the "n" or "m" becomes silent and causes the preceding vowel to become nasalized (i.e. pronounced with the soft palate extended downward so as to allow part of the air to leave through the nostrils). Exceptions are when the "n" or "m" is doubled, or immediately followed by a non-silent vowel. The prefixes en- and em- are always nasalized. The rules get more complex than this but may vary between dialects.

- digraphs French does not introduce extra letters or diacritics to specify its large range of vowel sounds and diphthongs, rather it uses specific combinations of vowels, sometimes with following consonants, to show which sound is intended.

- gemination : Within words, double consonants are generally not pronounced as geminates in modern French (but you can hear geminates in the cinema or TV news as far as the 70's, and in very refined elocution they still may occur). For example, "illusion" is pronounced [ilyzjő] and not [illyzjõ]. But gemination does occur between words. For example, "une info" ("a news") is pronounced [ynẽfo], whereas "une nympho" ("a nympho") is pronounced [ynnẽfo].

- accents are used sometimes for pronunciation, sometimes to distinguish similar words, and sometimes for etymology alone.

-

- Accents that affect pronunciation:

- The acute accent (l'accent aigu), "é" (e.g., école— school), means that the vowel is pronounced /e/ instead of the default /ə/,

- The grave accent (l'accent grave), "è" (e.g., élève— pupil) means that the vowel is pronounced /ɛ/ instead of the default /ə/,

- The diaeresis (le tréma) (e.g. naïve— foolish, Noël— Christmas) as in English, specifies that this vowel is pronounced separately from the preceding one, not combined,

- The cedilla (la cédille) "ç" (e.g., garçon— boy) means that the letter c is pronounced /s/ in front of the hard vowels A, O, and U. ("c" is otherwise /k/ before a hard vowel.) C is always pronounced /s/ in front of the soft vowels E, I, and Y, thus ç is never found in front of soft vowels,

- The circumflex (l'accent circonflexe) "ê" (e.g., forêt— forest) shows that an e is pronounced /ɛ/ and that an o is pronounced /o/. In standard French it also signifies a pronunciation of /ɑ/ for the letter a, but this differentiation is disappearing. In the late 19th century, the circumflex was used in place of 's' where that letter was not to be pronounced. Thus, forest became forêt and hospital became hôpital.

- Accents that affect pronunciation:

-

- Accents with no pronunciation effect:

- The circumflex does not affect the pronunciation of the letters i or u, and in most dialects, a as well (the circumflex on i and u is no longer compulsory : boite, chaine, Ile-de-France). It usually indicates that an s came after it long ago, as in hôtel.

- All other accents are used only to distinguish similar words, as in the case of distinguishing the adverbs là and où ("there", "where") from the article la and the conjunction ou ("the" fem. sing. , "or") respectively.

- Accents with no pronunciation effect:

Grammar

French grammar shares several notable features with most other Romance languages, including:

- the loss of Latin's declensions

- only two grammatical genders

- the development of grammatical articles from Latin demonstratives

- new tenses formed from auxiliaries

French word order is Subject Verb Object, except when the object is a pronoun, in which case the word order is Subject Object Verb. Some rare archaisms allow for different word orders.

Vocabulary

The majority of French words derive from vernacular or "vulgar" Latin or were constructed from Latin or Greek roots. There are often pairs of words, one form being popular (noun) and the other one savant (adjective), both originating from Latin. Example:

- brother: frère / fraternel < from latin FRATER

- finger: doigt / digital < from latin DIGITVS

- faith: foi / fidèle < from latin FIDES

- cold: froid / frigide < from latin FRIGIDVS

- eye: œil / oculaire < from latin OCVLVS

- the city Saint-Étienne has as inhabitants the Stéphanois

In some examples there is a common word from "vulgar" Latin and a more savant word from classical Latin or even Greek.

- Cheval - Concours équestre - Hippodrome

The French words which have developed from Latin are usually less recognisable than Italian words of Latin origin because as French developed into a separate language from Vulgar Latin, the unstressed final syllable of many words was dropped or elided into the following word.

It is estimated that 12 percent (4,200) of common French words found in a typical dictionary such as the Petit Larousse or Micro-Robert Plus (35,000 words) are of foreign origin. About 25 percent (1,054) of these foreign words come from English and are fairly recent borrowings. The others are some 707 words from Italian, 550 from ancient Germanic languages, 481 from ancient Gallo-Romance languages, 215 from Arabic, 164 from German, 160 from Celtic languages, 159 from Spanish, 153 from Dutch, 112 from Persian and Sanskrit, 101 from Native American languages, 89 from other Asian languages, 56 from Afro-Asiatic languages, 55 from Slavic languages and Baltic languages, and 144—about three percent—from other languages (Walter & Walter 1998).

Numerals

The French counting system is partially vigesimal: twenty (vingt) is used as a base number in the names of numbers from 60-99. So for example, the French word for 80 is quatre-vingts, which literally means 4 times 20, and soixante-quinze (literally "sixty-fifteen") means 75. This is comparable to the archaic English use of "score", as in "fourscore and seven" (87), or "threescore and ten" (70). Danish is another language with a base 20 system for counting.

Belgian French and Swiss French are different in this respect. In Belgium and Switzerland 70 and 90 are septante and nonante. In Switzerland, depending on the local dialect, 80 can be: quatre-vingts (Geneva, Neuchâtel, Jura) or huitante (Vaud, Valais, Fribourg).. In Belgium, however, quatre-vingts is universally used.

Writing system

French is written using the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, plus five diacritics (the circumflex accent, acute accent, grave accent, diaeresis, and cedilla) and the two ligatures (œ) and (æ).

French spelling, like English spelling, tends to preserve obsolete pronunciation rules. This is mainly due to extreme phonetic changes since the Old French period, without a corresponding change in spelling. Moreover, some conscious changes were made to restore Latin orthography:

- Old French doit > French doigt "finger" (Latin digitum)

- Old French pie > French pied "foot" (Latin pedem)

As a result, it is difficult to predict the spelling on the basis of the sound alone. Final consonants are generally silent, except when the following word begins with a vowel. For example, all of these words end in a vowel sound: pied, aller, les, finit, beaux. The same words followed by a vowel, however, may sound the consonants, as they do in these examples: beaux-arts, les amis, pied-à-terre.

On the other hand, a given spelling will almost always lead to a predictable sound, and the Académie française works hard to enforce and update this correspondence. In particular, a given vowel combination or diacritic predictably leads to one phoneme.

The diacritics have phonetic, semantic, and etymological significance.

- grave accent (à, è, ù): Over a or u, used only to distinguish homophones: à ("to") vs. a ("has"), ou ("or") vs. où ("where"). Over an e, indicates the sound /ɛ/.

- acute accent (é): Over an e, indicates the sound /e/, the ai sound in such words as English hay or neigh. It often indicates the historical deletion of a following consonant (usually an s): écouter < escouter. This type of accent mark is called accent aigu in French.

- circumflex (â, ê, î, ô, û): Over an a, e or o, indicates the sound /ɑ/, /ɛ/ or /o/, respectively (the distinction a /a/ vs. â /ɑ/ tends to disappear in many dialects). Most often indicates the historical deletion of an adjacent letter (usually an s or a vowel): château < castel, fête < feste, sûr < seur, dîner < disner. By extension, it has also come to be used to distinguish homophones: du ("of the") vs. dû (past participle of devoir "to owe"; note that dû is in fact written thus because of a dropped e: deu). (See Use of the circumflex in French)

- diaeresis or tréma (ë, ï, ü): Indicates that a vowel is to be pronounced separately from the preceding one: naïve, Noël. Diaeresis on y only occurs in some proper names (such as l'Haÿ-les-Roses) and in modern editions of old French texts. The diaresis on ü appears only in one non proper name: Capharnaüm. Nevertheless, since the 1990 orthographic rectifications (which are not applied at all by most French people), the diaeresis in words containing guë (such as aiguë or ciguë) may be moved onto the u: aigüe, cigüe. Words coming from German retain the old Umlaut if applicable but use French pronunciation, such as kärcher (trade mark of a pressure washer).

- cedilla (ç): Indicates that an etymological c is pronounced /s/ when it would otherwise be pronounced /k/. Thus je lance "I throw" (with c = [s] before e), je lançais "I was throwing" (c would be pronounced [k] before a without the cedilla).

There are two ligatures, which have various origins.

- The ligature œ is a mandatory contraction of oe in certain words. Some of these are native French words, with the pronunciation /œ/ or /ø/, e.g. sœur "sister" /sœʁ/, œuvre "work [of art]" /œvʁ/. Note that it usually appears in the combination œu; œil is an exception. Many of these words were originally written with the digraph eu; the o in the ligature represents a sometimes artificial attempt to imitate the Latin spelling: Latin bovem > Old French buef/beuf > Modern French bœuf. Œ is also used in words of Greek origin, as the Latin rendering of the Greek diphthong οι, e.g. cœlacanthe "coelacanth". These words used to be pronounced with the vowel /e/, but in recent years a spelling pronunciation with /ø/ has taken hold, e.g. œsophage /ezɔfaʒ/ or/øzɔfaʒ/. The pronunciation with /e/ is often seen to be more correct. The ligature œ is not used in some occurrences of the letter combination oe, for example, when o is part of a prefix (coexister).

- The ligature æ is rare and appears in some words of Latin and Greek origin like ægosome, ægyrine, æschne, cæcum, nævus or uræus . The vowel quality is identical to é /e/.

Some attempts have been made to reform French spelling, but few major changes have been made over the last two centuries.