German language

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Languages

| German Deutsch |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | IPA: [dɔʏ̯tʃ] | |

| Spoken in: | Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy ( South Tyrol), Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Switzerland and other countries. | |

| Region: | Central Europe, Western Europe | |

| Total speakers: | Native speakers: 120 million Second language: 22 million |

|

| Ranking: | 12 | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Germanic West Germanic High German German |

|

| Writing system: | Latin alphabet ( German variant) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language of: | Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Belgium, European Union. Regional or local official language in: Denmark, Italy, Romania (co-official language of Namibia until 1990). |

|

| Regulated by: | no official regulation | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | de | |

| ISO 639-2: | ger (B) | deu (T) |

| ISO/FDIS 639-3: | deu | |

|

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. See IPA chart for English for an English-based pronunciation key. | ||

German (Deutsch, [dɔʏ̯tʃ] ) is a West Germanic language and one of the world's major languages. Around the world, German is spoken by approximately 110 million native speakers and another 18 million non-native speakers.

Worldwide, German accounts for the most written translations into and from a language (according to the Guinness Book of Records).

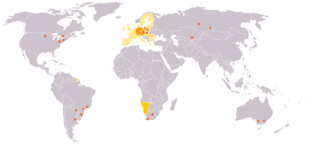

Geographic distribution

German is spoken primarily in Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, in two-thirds of Switzerland, in the South Tyrol province of Italy (in German, Südtirol), in the small East Cantons of Belgium, and in some border villages of the South Jutland County (in German, Nordschleswig, in Danish, Sønderjylland) of Denmark.

In Luxembourg (in German, Luxemburg), as well as in the French régions of Alsace (in German, Elsass) and parts of Lorraine (in German, Lothringen), the native populations speak several German dialects, and some people also master standard German (especially in Luxembourg), although in Alsace and Lorraine French has for the most part replaced the local German dialects in the last 40 years.

Some German-speaking communities still survive in parts of Romania, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and above all Russia and Kazakhstan, although forced expulsions after World War II and massive emigration to Germany in the 1980s and 1990s have depopulated most of these communities. It is also spoken by German-speaking foreign populations and some of their descendants in Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Scandinavia, Siberia.

Outside of Europe and the former Soviet Union, the largest German-speaking communities are to be found in the United States, Brazil and in Argentina where millions of Germans migrated in the last 200 years; but the great majority of their descendants no longer speak German. Additionally, German-speaking communities are to be found in the former German colony of Namibia, as well as in the other countries of German emigration such as Canada, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Venezuela (where Alemán Coloniero developed), South Africa, and Australia. See also Plautdietsch.

In the United States, the largest concentrations of German speakers are in Pennsylvania (Amish, Hutterites and some Mennonites speak Pennsylvania Dutch (a West Central German variety) and Hutterite German), Texas ( Texas German), Kansas ( Mennonites and Volga Germans), North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wisconsin and Indiana. Early twentieth century immigration was often to St. Louis, Chicago, New York, and Cincinnati. Most of the post-World War II wave are in the New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago urban areas, and in Florida. In Brazil the largest concentrations of German speakers are in Rio Grande do Sul (where Riograndenser Hunsrückisch was developed), Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Espírito Santo. Generally, German immigrant communities in the USA have lost their mother tongue more quickly than those who moved to South America, possibly because for German speakers, English is easier to learn than Portuguese or Spanish. But mainly, it was due to fervent anti-German sentiment in the United States before and after the World Wars, and the fear it caused in German-speakers of being attacked.

In Canada there are people of German ancestry throughout the country and especially in the west as well as in Ontario. There is a large and vibrant community in the city of Kitchener, Ontario.

In Mexico there are also large populations of German ancestry, mainly in the cities of: Mexico City, Puebla, Mazatlán, Tapachula, and larger populations scattered in the states of Chihuahua, Durango, and Zacatecas. Plautdietsch is a large minority language spoken in the north by the Mennonite communities, and is spoken by more than 200,000 people in Mexico, while standard German is spoken by the affluent German communities in Puebla, Mexico City & Quintana Roo.

German is the main language of about 96 million people in Europe (as of 2004), or 13.3% of all Europeans, being the second most spoken native language in Europe after Russian, above French (66.5 million speakers in 2004) and English (64.2 million speakers in 2004). German is the third most taught foreign language worldwide, also in the United States (after Spanish and French); it is the second most known foreign language in the EU (after English; see ) It is one of the official languages of the European Union, and one of the three working languages of the European Commission, along with English and French.

According to Global Reach (2004), 6.9% of the Internet population is German. According to Netz-tipp (2002), 7.7% of WebPages are written in German, making it second only to English. They also report that 12% of Google's users use its German interface.

Older statistics: Babel (1998) found somewhat similar demographics. FUNREDES (1998) and Vilaweb (2000) both found that German is the third most popular language used by websites, after English and Japanese.

History

The history of the German language begins with the High German consonant shift during the Migration period, separating South Germanic dialects from common West Germanic. The earliest testimonies of Old High German are from scattered Elder Futhark inscriptions, especially in Alemannic, from the 6th century, the earliest glosses ( Abrogans) date to the 8th and the oldest coherent texts (the Hildebrandslied, the Muspilli and the Merseburg Incantations) to the 9th century. Old Saxon at this time belongs to the North Sea Germanic cultural sphere, and Low Saxon should fall under German rather than Anglo-Frisian influence during the Holy Roman Empire.

As Germany was divided into many different states, the only force working for a unification or standardisation of German during a period of several hundred years was the general preference of writers trying to write in a way that could be understood in the largest possible area.

When Martin Luther translated the Bible (the New Testament in 1522 and the Old Testament, published in parts and completed in 1534) he based his translation mainly on this already developed language, which was the most widely understood language at this time. This language was based on Eastern Upper and Eastern Central German dialects and preserved much of the grammatical system of Middle High German (unlike the spoken German dialects in Central and Upper Germany that already at that time began to lose the genitive case and the preterit tense). In the beginning, copies of the Bible had a long list for each region, which translated words unknown in the region into the regional dialect. Roman Catholics rejected Luther's translation in the beginning and tried to create their own Catholic standard (gemeines Deutsch) — which, however, only differed from 'Protestant German' in some minor details. It took until the middle of the 18th century to create a standard that was widely accepted, thus ending the period of Early New High German.

German used to be the language of commerce and government in the Habsburg Empire, which encompassed a large area of Central and Eastern Europe. Until the mid-19th century it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. It indicated that the speaker was a merchant, an urbanite, not their nationality. Some cities, such as Prague (German: Prag) and Budapest ( Buda, German: Ofen), were gradually Germanised in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain. Others, such as Bratislava (German: Pressburg), were originally settled during the Habsburg period and were primarily German at that time. A few cities such as Milan (German: Mailand) remained primarily non-German. However, most cities were primarily German during this time, such as Prague, Budapest, Bratislava, Zagreb (German: Agram), and Ljubljana (German: Laibach), though they were surrounded by territory that spoke other languages.

Until about 1800, standard German was almost only a written language. At this time, people in urban northern Germany, who spoke dialects very different from Standard German, learnt it almost like a foreign language and tried to pronounce it as close to the spelling as possible. Prescriptive pronunciation guides used to consider northern German pronunciation to be the standard. However, the actual pronunciation of standard German varies from region to region.

Media and written works are almost all produced in standard German (often called Hochdeutsch in German) which is understood in all areas where German is spoken, except by pre-school children in areas which speak only dialect, for example Switzerland and Austria. However, in this age of television, even they now usually learn to understand Standard German before school age.

The first dictionary of the Brothers Grimm, the 16 parts of which were issued between 1852 and 1860, remains the most comprehensive guide to the words of the German language. In 1860, grammatical and orthographic rules first appeared in the Duden Handbook. In 1901, this was declared the standard definition of the German language. Official revisions of some of these rules were not issued until 1998, when the German spelling reform of 1996 was officially promulgated by governmental representatives of all German-speaking countries. Since the reform, German spelling has been in an eight-year transitional period where the reformed spelling is taught in most schools, while traditional and reformed spellings co-exist in the media. See German spelling reform of 1996 for an overview of the public debate concerning the reform with some major newspapers and magazines and several known writers refusing to adopt it.

The spelling reform of 1996 led to public controversy indeed to considerable dispute. Some state parliaments (Bundesländer) would not accept it (North Rhine Westphalia and Bavaria). The dispute landed at one point in the highest court which made a short issue of it, claiming that the states had to decide for themselves. After 10 years, intervention by the federal parliament finally led to official adoption just in time for the new school year of 2006. The cause of the controversy evolved around the question whether a language is part of the culture which must be preserved or a means of communicating information which has to allow for growth. German has no monopoly on this fundamental dilemma.

Classification and related languages

German is a member of the western branch of the Germanic family of languages, which in turn is part of the Indo-European language family.

Official status

Standard German is the only official language in Liechtenstein and Austria; it shares official status in Germany (with Danish, Frisian and Sorbian as minority languages), Switzerland (with French, Italian and Romansh), Belgium (with Dutch and French) and Luxembourg (with French and Luxembourgish). It is used as a local official language in German-speaking regions of Denmark, Italy, and Poland. It is one of the 20 official languages of the European Union.

It is also a minority language in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Namibia, Paraguay, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Tajikistan, Togo, the Ukraine and the United States.

German was once the lingua franca of central, eastern and northern Europe and remains one of the most popular foreign languages taught worldwide. 32% of citizens of the EU-15 countries say they can converse in German (either as a mother tongue or as a second/foreign language ). This is assisted by the widespread availability of German TV by cable or satellite.

Dialects

German dialects vs. varieties of standard German

In German linguistics, German dialects are distinguished from varieties of standard German.

- The German dialects are the traditional local varieties. They are traditionally traced back to the different German tribes. Many of them are hardly understandable to someone who knows only standard German, since they often differ from standard German in lexicon, phonology and syntax. If a narrow definition of language based on mutual intelligibility is used, many German dialects are considered to be separate languages (for instance in the Ethnologue). However, such a point of view is unusual in German linguistics.

- The varieties of standard German refer to the different local varieties of the pluricentric language standard German. They only differ slightly in lexicon and phonology. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional German dialects, especially in Northern Germany.

Dialects in Germany

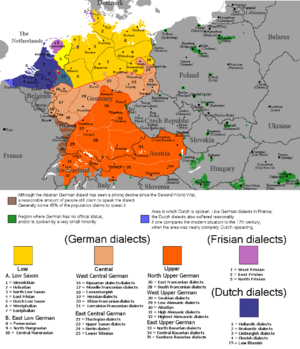

The variation among the German dialects is considerable, with only the neighbouring dialects being mutually intelligible. Some dialects are not intelligible to people who only know standard German. However, all German dialects belong to the dialect continuum of High German and Low Saxon languages. In the past (roughly until the end of the Second World War), there was a dialect continuum of all the continental West Germanic languages because nearly any pair of neighbouring dialects were perfectly mutually intelligible.

The German dialect continuum is traditionally divided into High German and Low German.

Low Saxon

Low Saxon varieties (spoken on German territory) are considered dialects of the German language by some, but a separate language by others. Sometimes, Low Saxon and Low Franconian are grouped together because both are unaffected by the High German consonant shift.

Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League. It was the predominant language in Northern Germany. This changed in the 16th century. In 1534, the Luther Bible, by Martin Luther was printed. This translation is considered to be an important step towards the evolution of the Early New High German. It aimed to be understandable to an ample audience and was based mainly on Central and Upper German varieties. The Early New High German language gained more prestige than Low Saxon and became the language of science and literature. Other factors were that around the same time, the Hanseatic league lost its importance as new trade routes to Asia and the Americas were established, and that the most powerful German states of that period were located in Middle and Southern Germany.

The 18th and 19th centuries were marked by mass education, the language of the schools being standard German. Slowly Low Saxon was pushed back and back until it was nothing but a language spoken by the uneducated and at home. Today, Low Saxon could be divided in two groups: Low Saxon varieties with a (reasonable/large/huge) standard German influx, and varieties of standard German with a Low Saxon influence ( Missingsch).

High German

High German is divided into Central German and Upper German. Central German dialects include Ripuarian, Moselle Franconian, Hessian, Thuringian, South Franconian, Lorraine Franconian and Upper Saxon. It is spoken in the southeastern Netherlands, eastern Belgium, Luxembourg, parts of France, and in Germany approximately between the River Main and the southern edge of the Lowlands. Modern Standard German is mostly based on Central German, but it should be noted that the common (but not linguistically correct) German term for modern Standard German is Hochdeutsch, that is, High German.

The Moselle Franconian varieties spoken in Luxembourg have been officially standardised and institutionalised and are therefore usually considered a separate language known as Luxembourgish.

Upper German dialects include Alemannic (for instance Swiss German), Swabian, East Franconian, Alsatian and Austro-Bavarian. They are spoken in parts of the Alsace, southern Germany, Liechtenstein, Austria, and in the German-speaking parts of Switzerland and Italy.

Wymysojer, Sathmarisch and Siebenbürgisch are High German dialects of Poland and Romania respectively. The High German varieties spoken by Ashkenazi Jews (mostly in the former Soviet Union) have several unique features, and are usually considered as a separate language, Yiddish. It is the only Germanic language that does not use the Latin alphabet as its standard script.

The dialects of German which are or were primarily spoken in colonies or communities founded by German speaking people resemble the dialects of the regions the founders came from. For example, Pennsylvania German resembles dialects of the Palatinate, and Hutterite German resembles dialects of Carinthia, while Venezuelan Alemán Coloniero is a Low Alemannic variant.

In Brazil the largest concentrations of German speakers ( German Brazilians) are in Rio Grande do Sul, where Riograndenser Hunsrückisch was developed, especially in the areas of Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Espírito Santo.

In the United States, the teaching of the German language to latter-age students has given rise to a pidgin variant which combines the German language with the grammar and spelling rules of the English language. It is often understandable by either party. The speakers of this language often refer to it as Amerikanisch or Amerikanischdeutsch, although it is known in English as American German. However, this is a pidgin, not a dialect. In the USA, in the Amana Colonies in the state of Iowa Amana German is spoken.

Standard German

In German linguistics, only the traditional regional varieties are called dialects, not the different varieties of standard German.

Standard German has originated not as a traditional dialect of a specific region, but as a written language. However, there are places where the traditional regional dialects have been replaced by standard German; this is the case in vast stretches of Northern Germany, but also in major cities in other parts of the country and to some extent in Vienna.

Standard German differs regionally, especially between German-speaking countries, especially in vocabulary, but also in some instances of pronunciation and even grammar. This variation must not be confused with the variation of local dialects. Even though the regional varieties of standard German are to a certain degree influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a pluricentric language.

In most regions, the speakers use a continuum of mixtures from more dialectical varieties to more standard varieties according to situation.

In the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, mixtures of dialect and standard are very seldom used, and the use of standard German is largely restricted to the written language. Therefore, this situation has been called a medial diglossia. Standard German is only spoken with people who do not understand the Swiss German dialects at all. It is expected to be used in school.

Grammar

German is an inflected language.

Noun inflection

German nouns inflect into:

- one of four declension classes (cases): nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative.

- one of three genders: masculine, feminine, or neuter. Word endings sometimes reveals grammatical gender for instance nouns ending in ...ung, ...schaft or ...eit are feminine in ...chen or ...lein are neuter; others are controversial (Ex. Becken = basin or Radio = radio) sometimes depending on the region in which it is spoken. To avoid a misunderstanding usually the sentence can be reorganized.

- two numbers: singular and plural

Although German is usually cited as an outstanding example of a highly inflected language, it should be noted that the degree of inflection is considerably less than in Old German, or in Icelandic today. The three genders have collapsed in the plural, which now behaves, grammatically, somewhat as a fourth gender. With four cases and three genders plus plural there are 16 distinct possible combinations of case and gender/number, but presently there are only six forms of the definite article used for the 16 possibilities. Inflection for case on the noun itself is required in the singular for strong masculine and neuter nouns in the genitive and sometimes in the dative. Both of these cases are losing way to substitutes in informal speech. The dative ending is considered somewhat old-fashioned in many contexts and often dropped, but it is still used in sayings and in formal speech or in written language. Weak masculine nouns share a common case ending for genitive, dative and accusative in the singular. Feminines are not declined in the singular. The plural does have an inflection for the dative. In total, seven inflectional endings (not counting plural markers) exist in German: -s, -es, -n, -ns, -en, -ens, -e.

In the German orthography, nouns and most words with the syntactical function of nouns are capitalised, which is supposed to make it easier for readers to find out what function a word has within the sentence. On the other hand, things get more difficult for the writer. This spelling convention is almost unique to German today (shared perhaps only by the closely related Luxembourgish language), although it was historically common in other languages (e.g., Danish), too.

Like most Germanic languages, German forms left-branching noun compounds, where the first noun modifies the category given by the second, for example: Hundehütte (eng. doghouse). Unlike English, where newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in open form with separating spaces, German (like the other German languages) nearly always uses the closed form without spaces, for example: Baumhaus (eng. tree house). Like English, German allows arbitrarily long compounds, but these are rare. (See also English compounds.)

The longest German word verified to be actually in (albeit very limited) use is Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz. There is even a child's game played in kindergartens and primary schools where a child begins the spelling of a word (which is not told) by naming the first letter. The next one tells the next letter, the third one tells the third and so on. The game is over when a child cannot think of another letter to be added to the word (see Ghost). Another popular child's game consists of building a noun compound. The first child starts with a noun or more commonly already a compound (Donaudampfschifffahrtskapitän (Danube Steamboat captain) is somewhat popular and infamous). The next child has to append another noun so that the compound still has a sensible meaning (Example: Donaudampfschifffahrtskapitän -> Donaudampfschiffahrtskapitänsmütze (Danube Steamboat captain's hat) -> Donaudampfschifffahrtskapitänsmützenfabrik (Danube Steamboat captain's hat factory, and so on). The game ends when the next child cannot think of a word to append that would yield a meaningful compound.

Verb inflection

Standard German verbs inflect into:

- one of two conjugation classes, weak and strong (like English).

(There is actually a third class, known as mixed verbs, which exhibit inflections combining features of both the strong and weak patterns.)

- three persons: 1st, 2nd, 3rd.

- two numbers: singular and plural

- three moods: Indicative, Subjunctive, Imperative

- two genera verbi: active and passive; the passive being composed and dividable into static and dynamic.

- two non-composed tenses (Present, Preterite) and four composed tenses (Perfect, Plusquamperfect, Future I, Future II)

- distinction between grammatical aspects is rendered by combined use of subjunctive and/or Preterite marking; thus: neither of both is plain indicative voice, sole subjunctive conveys second-hand information, subjunctive plus Preterite marking forms the conditional state, and sole Preterite is either plain indicative (in the past), or functions as a (literal) alternative for either second-hand-information or for the conditional state of the verb, when one of them may seem undistinguishable otherwise.

- distinction between perfect and progressive aspect is and has at every stage of development been at hand as a productive category of the older language and in nearly all documented dialects, but, strangely enough, is nowadays rigorously excluded from written usage in its present normalised form.

- disambiguation of completed vs. uncompleted forms is widely observed and regularly generated by common prefixes (blicken - to look, erblicken - to see [unrelated form: sehen - to see]).

There are also many ways to expand, and sometimes radically change, the meaning of a base verb through several prefixes. Examples: haften=to stick, verhaften=to imprison; kaufen=to buy, verkaufen=to sell; hören=to hear, aufhören=to cease.

Syntax

The word order is generally more rigid than in English except for nouns (see below). One word order is for a main and another for relative clauses. In normal positive sentences the inflected verb always has position 2; In questions, exclamations, and wishes, it always has position 1. In relative clauses the verb is supposed to occur at the very end. In speech some clauses are excused from this rule. For example in a subordinate clause introduced by the German word for "because" (weil) the verb quite often occupies the same order as in a main clause. Correct is ... weil ich pleite bin. (...because I'm broke). In the vernacular you hear ...weil ich bin pleite.. This may be caused by mixing weil with a second, alternative word for "because", denn, which confusingly is used with the main clause order (...denn ich bin pleite.).

Sentences using modal verbs separate the auxiliary putting the infinitive at the end. For example, the sentence in English "Should he go home?" would be rearranged in German to say "Should he home go?" (Soll er nach Hause gehen?). Thus in sentences with several subordinate or relative clauses verbs tend to gather at the end. The reader or listener then has the job of reconnecting these verbs individually to the subjects to which they belong. Compare the mental acrobatics to rearrange prepositions in the following English sentence: What did you bring that book that I don't like to be read to out of up for?

To ease the German syntax, a rule has been imposed to limit the number of infinitives at the end to two, placing the third infinitive or auxiliary verb that would have gone to the end to the beginning of the chain of verbs. In the sentence "Should he move into the house that he just had renovated?" would be rearranged to "Should he into that house move which he just had renovate let?". (Soll er in das Haus einziehen, das er gerade hat renovieren lassen?). If there are more than three, all others are relocated to the beginning of the chain. Needless to say the rule is not exclusively applied. Many native speakers spend their entire lives without ever using it outside of school at all. It's found in newspapers, radio or tv reports and in educated circles. Mostly the situation is avoided by reorganizing the sentence.

The position of a noun as a subject or object in a german sentence doesn't affect the meaning of the sentence as it would in English. In a declarative sentence in English if the subject does not occur before the predicate the sentence could well be misunderstood. In a headline, for example, "Man bites dog" it's clear who did what to whom. To exchange the place of the subject with that of the object changes the meaning completely. In other words the word order in a sentence conveys significant information. In German, nouns and articles are declined as in Latin thus indicating its case as nominative or accusative (among others). The above example in German would be Ein Mann beißt den Hund or Den Hund beißt ein Mann with exactly the same meaning. If the articles are omitted, which is sometimes done in headlines (Hund beißt Mann), it's like in English, the first noun is the subject. The noun following the predicate is the object.

Except for cases of emphasis adverbs of time have to appear in the third place in the sentence (just after the predicate). Otherwise the speaker would be recognised as non-German. For instance the German word order (in English) is: We're going tomorrow to town. (Wir gehen morgen in die Stadt.)

Many German verbs are separable meaning that the verb's prefix (often a preposition) is split off and moved to the end of the sentence, hence considered by some to be a "resultative particle", unique to the German language. For example, mitgehen meaning "to go with" would be split giving Gehen Sie mit? (Are you also going?). Although ending English sentences with a preposition is sometimes frowned upon, this construction is standard in German. For more info see Preposition stranding.

Lexicon

Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, although there are significant minorities of words derived from Latin, French, and most recently English (which, in English, is known as Germish or in German as Denglisch). At the same time, the effectiveness of the German language in forming rivals for foreign words from its inherited Germanic stem repertory is great. Thus, Notker Labeo was able to translate Aristotelian treatises in pure (Old High) German in the decades after the year 1000.

Still today, many low-key scholarlymovements try to promote the Ersatz (substitution) of virtually all foreign words with German alternatives: ancient, dialectal, or neologisms. It is claimed that this would also help in spreading modern or scientific notions among the less educated, and thus democratise public life, too. (Jurisprudence in Germany, for example, uses perhaps the “purest” tongue in terms of "Germanness" to be found today.)

The coining of new, autochthonous words, gave German a vocabulary of an estimated 40,000 words as early as the ninth century (in comparison, Latin, with a written tradition of nearly 2,500 years in an empire which ruled the Mediterranean, has grown to no more than 45,000 words today). The vocabulary of German is smaller than that of English, which has the largest lexicon of any language.

Writing system

Present

German is now written using the Latin alphabet. In addition to the 26 standard letters, German has three vowels with Umlaut, namely ä, ö and ü, as well as the Eszett or scharfes S (sharp "s") ß.

In German spelling before the reform of 1996, ß replaced ss after long vowels and diphthongs and before consonants, word-, or partial-word-endings. In reformed spelling, ß replaces ss only after long vowels and diphthongs. Since there is no capital "ß", in capitalised writing "ß" is always written as "SS" (example: Maßband (Tape measure) in normal writing, but MASSBAND in capitalised writing). In Switzerland, ß is not used at all.

Umlaut vowels (ä, ö, ü) can be circumscribed with ae, oe, and ue if the umlauts are not available on the keyboard used. In the same manner "ß" can be circumscribed as "ss". German readers understand those circumscriptions (although they look unusual), but they are avoided if the regular umlauts are available since "ae", "oe" and "ue" can in rare cases also mean a regular vowel with silent "e", in the manner of "ah", "oh" and "uh". This is often used in Westphalia, examples are the cities "Raesfeld" [ˡraːsfɛlt] and "Coesfeld" [ˡkoːsfɛlt] near Münster.

Unfortunately there is still no general agreement exactly where these Umlauts occur in the sorting sequence. Telephone directories treat them by replacing them with the base vowel followed by an "e", whereas dictionaries use just the base vowel. As an example in a telephone book "Ärzte" occurs after "Adressenverlage" but before "Anlagenbauer" (because "Ä" is replaced by "Ae"). In a dictionary "Ärzte" occurs after "Arzt" but before "Asbest" (because "Ä" is treated as "A").

Past

Until the early 20th century, German was mostly printed in blackletter typefaces (mostly in Fraktur, but also in Schwabacher) and written in corresponding handwriting (for example Kurrent and Sütterlin). These variants of the Latin alphabet are very different from the serif or sans serif Antiqua typefaces used today, and particularly the handwritten forms are difficult for the untrained to read. The printed forms however are claimed by some to be actually more readable when used for printing Germanic languages. The Nazis initially promoted Fraktur and Schwabacher since they were considered Aryan, although they later abolished them in 1941 by claiming that these letters were Jewish.

Phonology

Vowels

The German vowels A, O and U with or without umlauts are pronounced long or short depending normally upon what follows it in the syllable. If the vowel is at the end of a syllable or followed by a single consonant it is normally pronounced long (Ex. Hof = yard pronounced like the o in the English word "hope"). If it is followed by a double consonant like ff, ss or tt it is nearly always short (Ex. Hoffnung = Hope, pronounced similar to the first o in the English word "bottom"). A vowel followed by "st" is sometimes short (Ex. Posten = entry on an invoice) and sometimes long (Ex. Kloster = convent). These rules are unfortunately neither consistent nor universal. In central Germany (Hessen), for example, the o in the proper name "Hoffmann" is pronounced long as if the name were spelled "Hofmann". The combination "ch" is always treated as a single consonant. Thus when following a vowel the vowel should be pronounced long. In the combinations "ck" and "dt" the first letter is silent. It's only there to show that the preceding vowel should be pronounced short. This rule is not universally observed. According to the rule the e in the name Mecklenburg, for example, should be pronounced with short [ɛ] (like the English "e" in bet), but it is often pronounced with long [eː] (like the "ai" in a Scottish English pronunciation of bait). This is caused by the spelling traditions of Low German dialects, where "ck" was used to indicate a long vowel and occurs mainly in old names from this region. The word Städte (= cities), for example, is pronounced with a short vowel ([ˈʃtɛtə]) by some (Jan Hofer, ARD Television) and with a long vowel ([ˈʃtɛːtə]) by others (Marietta Slomka, ZDF Television).

The digraph ei is pronounced [ai] (e.g. meine = mine). The digraph ie is pronounced [iː] (e.g. diese = this), as is i followed by a single consonant (e.g. Berlin). However, the feminine suffix -in (e.g. Kanzlerin = female chancellor) is pronounced [ɪn], with a short vowel.

Umlaut ( ¨ )

- Ä: In its short form comes close to the e of the English word bed. Its long form has no equivalent in English but comes close to the /eir/ in "their".

- Ö: In its long form comes close to the ir sound in the English word "bird". (Ex. Brötchen = roll (to eat)).

- Ü: In its long form comes close to the yu sound in the English words "mule" or "music". (Ex. München = Munich). It is pronounced similarly to the French "u".

Consonants

- C standing alone is not a germanic letter. It never occurs at the beginning of a germanic word. In borrowed words together with "h" there is no single agreement on the pronunciation. It's pronounced either as the English "sh" in or as "k". (Ex. China( = China) or Chemie (= Chemistry).

- Ch occurs most often but has no equivalent in English. There are two slightly different ways of pronunciation in High German: After e and i it sounds a bit like the "h" in "huge", but is pronounced more sharply and strongly (Ex. mich = me). After a, o and u (dark vowels) it is as if you tried to pronounce k without cutting off the air above the tongue. (Ex. Rache = revenge). In western Germany (Rheinland) it is in any position pronounced as sch equivalent to the English sh in the word shoe. In this area distinguishing between such words as Kirchen (Churches) and Kirschen (cherries) is left up to the context.

- H is aspirated, as in "Home" at the beginning of a syllable. After a vowel it's silent and just lengthens the vowel. (Ex. Reh = Deer)

- W is pronounced as /v/ as in "Vacation" (Ex. Was = What)

- S is pronounced as /z/ as in "Zebra" (Ex. Sonne = Sun)

- Z is always pronounced as /ts/.

- F is pronounced as /f/ as in "Father".

- V is pronounced as /f/ in words of Germanic origin (Ex. Vater = Father) and as /v/ in other words (Ex. Evidenz = Evidence)

- ß is never used at the beginning of a word. It is pronounced as /s/ as in "see" (Ex. Schoß = lap).

The th sound common in English actually came from Anglo Saxon. It survived on the continent up to Old High German then disappeared with the consonant shifts about the 9th century.

Diphthongs

- AU occurs often and is pronounced as the English /au/ in house (Ex. Haus = house)

- EI is pronounced as /ai/ in "I" (Ex. mein = mine)

- AI is pronounced the same as their EI. (Ex. Mai = May)

- IE is pronounced as the long "i" of bee. (Ex. Tier = Animal)

- EU is pronounced as /oi/ in boy. (Ex. Treu = Loyal).

- ÄU is pronounced the same as their diphthong EU. (Ex. Fräulein = Miss)

Cognates with English

There are many German words that are cognate to English words. Most of them are easily identifiable and have almost the same meaning.

| German | Meaning of German word | English cognate |

|---|---|---|

| Abend | eve/evening | eve from Old E.æfen |

| auf | up | up |

| aus | out,up | out |

| beginnen, begann, begonnen | to begin, began, begun | to begin, began, begun |

| best- | best | best |

| Bett | bed | bed |

| Bier | beer | beer |

| Butter | butter | butter |

| essen | to eat | to eat |

| fallen, fiel, gefallen | to fall, fell, fallen | to fall, fell, fallen |

| Faust | fist | fist |

| Finger | finger | finger |

| Gott | God | God |

| haben | to have | to have |

| heit(suffix) | ity(latin suffix) | hood(suffix) |

| Haus | house | house |

| heißen | is called | hight |

| hören | to hear | hear |

| ist, war | is, was | is, was |

| Katze | cat | cat |

| kommen, kam, gekommen | to come, came, come | to come, came, come |

| Laus | louse | louse |

| Läuse | lice | lice |

| lachen | to laugh | to laugh |

| Maus | mouse | mouse |

| Milch | milk | milk |

| müssen | must | must |

| Mäuse | mice | mice |

| Nacht | night | night |

| Pfeife | pipe | pipe, fife |

| Schiff | ship | ship |

| schwimmen | to swim | to swim |

| singen, sang, gesungen | to sing, sang, sung | to sing, sang, sung |

| sinken, sank, gesunken | to sink, sank, sunk | to sink, sank, sunk |

| Sommer | summer | summer |

| springen, sprang, gesprungen | to jump, jumped, jumped | to spring, sprang, sprung |

| Tag | day | day |

| Wetter | weather | weather |

| Wille | will (noun) | will |

| wir, uns | we, us | we, us |

| Winter | winter | winter |

When these cognates have slightly different consonants, this is often due to the High German consonant shift.

There are cognates whose meanings in either language have changed through the centuries. It is sometimes difficult for both English and German speakers to discern the relationship. On the other hand, once the definitions are made clear, then the logical relation becomes obvious.

| German | Meaning of German word | English cognate | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| antworten | to answer | an-word | the cognate prefix Ger.'ant' is equal to Old E.'and-'〈"against"〉(→an).'wort'=word,'swer'=swear,so the suffix isn't cognate. |

| Baum | tree | beam | Both derive from West Germanic *baumoz meaning "tree". It is the English one which, in Anglo-Saxon and Old English, has radically changed its meaning several times. |

| bekommen | to get | to become | |

| drehen | to turn | to throw | cf. to "throw" (make) a pot by turning it on a wheel |

| ernten | to harvest | to earn | |

| fahren | to go | to fare | O.E. faran "to journey, to make one's way," from P.Gmc. *faranan (cf. Goth. faran, Ger. fahren), from PIE *por- "going, passage" |

| fechten | to fence (sport) | to fight | |

| Gift | poison | gift | the original meaning of Gift in German can still be seen in the german deflection Mitgift "dowry" |

| Hund | dog | hound | |

| kaufen | to buy | cheap, chapman | |

| Knabe (formal) | boy | knave | |

| Knecht | servant | knight | |

| Kopf | head | cup | Latin cuppa 'bowl'; cf. French tête, from Latin testa 'shell/bowl'. Here English kept the original Germanic word for "head" while German borrowed a Latin word (the native German word is Haupt, but now used for other purposes). The German word for cup, Tasse, is also of Latin (French) origin |

| machen | to do,to work | to make | |

| nehmen | to take | numb | sensation has been "taken away"; cf. German benommen, 'dazed' |

| raten | to guess, to advise | to read | cf. riddle, akin to German Rätsel |

| ritzen | to scratch | to write | |

| Schmerz | pain | smart | The verb smart retains this meaning |

| schlecht | bad | slight | Sense of Ger. cognate schlecht developed from "smooth, plain, simple" to "bad," and as it did it was replaced in the original senses by schlicht, a back-formation from schlichten "to smooth, to plane," a derivative of schlecht in the old sense. |

| stadt | a city | stead | |

| sterben | to die | to starve | |

| sich rächen | to take revenge | to wreak (havoc) | |

| Tisch | table | dish, desk | Latin discus |

| Vieh | cattle | fee | from O.E. 'feoh' "money, property, cattle" |

| Wald | forest | weald | |

| werden | to become | weird | see wyrd |

| werfen | to throw | to warp | |

| Zeit | time | tide | the root is re-used in German Gezeiten as Tiden ('tides') |

German and English also share many borrowings from other languages, especially Latin, French and Greek. Most of these words have the same meaning, while a few have subtle differences in meaning. As many of these words have been borrowed by numerous languages, not only German and English, they are called internationalisms in German linguistics.

| German | Meaning of German word | language of origin |

|---|---|---|

| Armee | army | French |

| Arrangement | arrangement | French |

| Chance | opportunity | French |

| Courage | courage | French |

| Chuzpe | chutzpah | Yiddish |

| Disposition | disposition | Latin |

| Feuilleton | feuilleton | French |

| Futur | future tense | Latin |

| Boje | buoy | Dutch |

| Genre | genre | French |

| Mikroskop | microscope | Greek |

| Partei | political party | French |

| Position | position | Latin |

| positiv | positive | Latin |

| Prestige | prestige | French |

| Psychologie | psychology | Greek |

| Religion | religion | Latin |

| Tabu | taboo | Tongan |

| Zigarre | cigar | Spanish |

| Zucker | sugar | Sanskrit, via Arabic |

Examples of German

| Translation | Phrase | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| German | Deutsch | /dɔɪ̯tʃ/ |

| Hello | Hallo | /ˈhaloː/ |

| I am called Hans. | Ich heiße Hans. | /ʔɪç haɪ̯sə hans/ |

| My name is Hans. | Mein Name ist Hans. | /maɪ̯n namə ʔɪst hans/ |

| Good morning | Guten Morgen | /ˈguːtən ˈmɔɐ̯gən/ |

| Good day | Guten Tag | /ˈguːtən taːk/ |

| Good evening | Guten Abend | /ˈguːtən ˈaːbənt/ |

| Good night | Gute Nacht | /ˈguːtə naχt/ |

| Good-bye | Auf Wiedersehen | /ʔaʊ̯f ˈviːdɐˌzeːn/ |

| Please | Bitte | /ˈbɪtə/ |

| You are welcome | Bitte | /ˈbɪtə/ |

| Thank you | Danke | /ˈdaŋkə/ |

| That | Das | /das/ |

| How much? | Wie viel? | /vi fiːl/ |

| Yes | Ja | /jaː/ |

| No | Nein | /naɪ̯n/ |

| I would like that, please | Ich möchte das, bitte | /ʔɪç mœçtə das ˈbɪtə/ |

| Where is the toilet? | Wo ist die Toilette? | /voː ʔɪst diː toa̯ˈlɛtə/ |

| Generic toast | Prosit Prost |

/ˈproːziːt/ /proːst/ |

| Do you speak English? | Sprechen Sie Englisch? | /ˈʃprɛçən ziː ˈʔɛŋlɪʃ/ |

| I don't understand | Ich verstehe nicht | /ʔɪç fɐˈʃteːə nɪçt/ |

| Excuse me | Entschuldigung | /ʔɛntˈʃʊldɪgʊŋ/ |

| I don't know | Ich weiß nicht | /ʔɪç vaɪ̯s nɪçt/ |

Names for German in other languages

Because of the turbulent history of both Germany and the German language, the names that other peoples have chosen to use to refer to it varies more than for most other languages.

In Italian the sole name for German is still tedesco, from the Latin teutiscum, meaning "vernacular".

Romanian used to use in the past the Slavonic term "nemţeşte", but "Germană" is now widely used. Hungarian "német" is also of Slavonic origin. The Arabic name for Austria, النمسا ("an-namsa"), is derived from the Slavonic term.

Note also that, although the Russian term for the language is немецкий (nemetskij), the country is Германия (Germaniya). However, in some other Slavic languages, as with Polish, the country name (Niemcy (pl)) is similar to the name of the language, (język) niemiecki.

A possible explanation for the use of "mute" (nemoj) to refer to German (and also to Germans) in Slavic languages is that Germans were the first people Slavic tribes encountered, with whom they could not communicate. The corresponding experience for the Germans was with the Volcae, whose name they subsequently also applied to the Slavs, see etymology of Vlach. Another less-attested possibility is that the Slavs first encountered a Germanic tribe called the Nemetes (which was mentioned by the Romans), and later meeting other Germans, applied the tribe's name "Nemetes" to all Germans.

Hebrew traditionally (nowadays this is not the case) used the Biblical term Ashkenaz (Genesis 10:3) to refer to Germany, or to certain parts of it, and the Ashkenazi Jews are those who originate from Germany and Eastern Europe and formerly spoke Yiddish as their native language, derived from Middle High German.

See also Names for Germany.