Spain

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Countries; European Countries

| Reino de España Kingdom of Spain |

|||||

|

|||||

| Motto: Plus Ultra (Latin: "Further Beyond") |

|||||

| Anthem: Marcha Real 1 (Spanish: "Royal March") |

|||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Madrid |

||||

| Official languages | Spanish. In some autonomous communities, Aranese, Basque, Catalan and Galician are co-official. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||

| - King | Juan Carlos I | ||||

| - Prime Minister | José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero | ||||

| Formation | 15th century | ||||

| - Dynastic union | 1516 | ||||

| - Unification | |||||

| - De facto | 1716 | ||||

| - De jure | 1812 | ||||

| Accession to EU | January 1, 1986 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 505,992 km² ( 51st) 195,364 sq mi |

||||

| - Water (%) | 1.04 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 1 January 2006 estimate | 44,395,286 ( 29th) | ||||

| - 2005 census | 44,108,530 | ||||

| - Density | 87,8/km² ( 106th) 220/sq mi |

||||

| GDP ( PPP) | 2005 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $1.029 trillion ( 9th) | ||||

| - Per capita | $26,320 ( 25th) | ||||

| HDI (2004) | 0.938 (high) ( 19th) | ||||

| Currency | Euro ( €)2 ( EUR) |

||||

| Time zone | CET3 ( UTC+1) | ||||

| - Summer ( DST) | CEST ( UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .es4 | ||||

| Calling code | +34 | ||||

| 1 Also serves as the Royal anthem. 2 Prior to 1999: Spanish Peseta. |

|||||

Spain, officially the Kingdom of Spain (Spanish: Reino de España, short form: ![]() España), is a country located in Southern Europe, with two small exclaves in North Africa (both bordering Morocco). Spain is a democracy which is organized as a parliamentary monarchy. It is a developed country with the ninth-largest economy in the world. It is the largest of the three sovereign nations that make up the Iberian Peninsula—the others are Portugal and the microstate of Andorra.

España), is a country located in Southern Europe, with two small exclaves in North Africa (both bordering Morocco). Spain is a democracy which is organized as a parliamentary monarchy. It is a developed country with the ninth-largest economy in the world. It is the largest of the three sovereign nations that make up the Iberian Peninsula—the others are Portugal and the microstate of Andorra.

To the west and to the south of Galicia, Spain borders Portugal. To the south, it borders Gibraltar (a British overseas territory) and, through its cities in North Africa ( Ceuta and Melilla), Morocco. To the northeast, along the Pyrenees mountain range, it borders France and the tiny principality of Andorra. It also includes the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea, the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean and a number of uninhabited islands on the Mediterranean side of the strait of Gibraltar, known as Plazas de soberanía, such as the Chafarine islands, the isle of Alborán, the "rocks" (peñones) of Vélez and Alhucemas, and the tiny Isla Perejil. In the northeast along the Pyrenees, a small exclave town called Llívia in Catalonia is surrounded by French territory.

The term Spain (España in Spanish) is derived from the Roman name for the region: Hispania.

History

Prehistory and Pre-Roman peoples in the Iberian Peninsula

The earliest records of hominids living in Europe to date has been found in the Spanish cave of Atapuerca which has become a key site for world Paleontology due to the importance of the fossils found there, dated roughly 1,000,000 years ago.

Modern humans in the form of Cro-Magnons began arriving in the Iberian Peninsula from north of the Pyrenees some 35,000 years ago. The more conspicuous sign of prehistoric human settlements are the famous paintings in the northern Spanish Altamira (cave), which were done ca. 15,000 BCE and are regarded, along with those in Lascaux, France, as paramount instances of cave art.

The earliest urban culture documented is that of the semi-mythical southern city of Tartessos, pre- 1100 BCE. The seafaring Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians successively settled along the Mediterranean coast and founded trading colonies there over a period of several centuries. Around 1100 BCE, Phoenician merchants founded the trading colony of Gadir or Gades (modern day Cádiz) near Tartessos. In the 9th century BCE the first Greek colonies, such as Emporion (modern Empúries), were founded along the Mediterranean coast on the East, leaving the south coast to the Phoenicians. The Greeks are responsible for the name Iberia, apparently after the river Iber ( Ebro in Spanish). In the 6th century BCE the Carthaginians arrived in Iberia while struggling first with the Greeks and shortly after with the Romans for control of the Western Mediterranean. Their most important colony was Carthago Nova (Latin name of modern day Cartagena).

The native peoples which the Romans met at the time of their invasion in what is now known as Spain were the Iberians, inhabiting from the Southwest part of the Peninsula through the Northeast part of it, and then the Celts, mostly inhabiting the north and northwest part of the Peninsula. In the inner part of the peninsula, where both groups were in contact, a mixed, distinctive, culture was present, the one known as Celtiberian.

Roman Empire and Germanic Invasions

The Romans arrived in the Iberian peninsula during the Second Punic war in the 2nd century BCE, and annexed it under Augustus after two centuries of war with the tenacious Celtic and Iberian tribes (from whom they copied the short sword known as falcata). These, along with the Phoenician, Greek and Carthaginian coastal colonies, became the province of Hispania. It was divided into Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior during the late Roman Republic; and, during the Roman Empire, Hispania Taraconensis in the northeast, Hispania Baetica in the south and Lusitania (province with capital in the city of Emerita Augusta) in the southwest.

Hispania supplied Rome with food, olive oil, wine and metal. The emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius and Theodosius I, the philosopher Seneca and the poets Martial, Quintilian and Lucan were born in Spain. The Spanish Bishops held the Council at Elvira in 306. The collapse of the Western Roman empire did not lead to the same wholesale destruction of Western classical society as happened in areas like Britain, Gaul and Germania Inferior during the Dark Ages, even if the institutions, infrastructure and economy did suffer considerable degradation. Spain's present languages, its religion, and the basis of its laws originate from this period. The centuries of uninterrupted Roman rule and settlement left a deep and enduring imprint upon the culture of Spain.

The first hordes of Barbarians to invade Hispania arrived in the 5th century, as the Roman empire decayed. The tribes of Goths, Visigoths, Swebians ( Suebi), Alans, Asdings and Vandals, arrived to Spain by crossing the Pyrenees mountain range. They were all of Germanic origin. This led to the establishment of the Swebian Kingdom in Gallaecia, in the northwest, and the Visigothic Kingdom elsewhere. (For a while, the Germans lived under their law while the much more numerous Spaniards continued more or less to live under Roman law.) The Visigothic Kingdom eventually encompassed the entire Iberian Peninsula with the Roman Catholic conversion of the Goth monarchs. The famous horseshoe arch, which was adapted and perfected by the later Muslim era builders was in fact originally an example of Visigothic art.

Muslim Iberia

In the 8th century, nearly all the Iberian peninsula, which had been under Visigothic rule, was quickly conquered (711–718), by mainly Berber Muslims (see Moors), who had crossed over from North Africa, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad. Visigothic Spain was the last of a series of lands conquered in a great westward charge by the Islamically inspired armies of the Umayyad empire. Indeed they continued northwards until they were defeated in central France at the Battle of Tours in 732. Astonishingly the invasion started off as an invitation from a Visigoth faction within Spain for support. But instead the Moorish army, having defeated King Roderic proceeded to conquer the peninsula for itself. The Roman Catholic populace, unimpressed with the constant internal feuding of the Visigothic leaders, often stood apart from the fighting, often welcoming the new rulers, thereby forging the basis of the distinctly Spanish-Muslim culture of Al-Andalus. Only three small counties in the mountains of the north of Spain managed to cling to their independence: Asturias, Navarra and Aragon, which eventually became kingdoms.

The Muslim emirate proved strong in its first three centuries; stopping Charlemagne's massive forces at Saragossa and, after a serious Viking attack, established effective defences. Indeed it became a terror in its own right to Christian neighbours, with its "al-jihad fil-bahr" (holy war at sea). Christian Spain struck back from its mountain redoubts by seizing the lands north of the Duero river, and the Franks were able to seize Barcelona (801) and the Spanish Marches), but save for these and some other small incursions in the north, the Christians were unable to make headway against the superior forces of Al-Andalus for several centuries. It was only in the 11th century that the break up of Al-Andalus led to the creation of the Taifa kingdoms, who attempted to outshine each other in art and culture and were often at war, became vulnerable to the consolidating power of Spain's Christian kingdoms.

The Moorish capital was Córdoba, in southern Spain. During this time large populations of Jews, Christians and Muslims lived in close quarters, and at its peak some non-Muslims were appointed to high offices under the some of the more lenient Muslim rulers. At its best it produced exquisite architecture and art, and Muslim and Jewish scholars played a major part in reviving the tradition of classical Greek philosophy, mathematics and science in Western Europe, whilst making their own contributions to it. However, there were restrictions on non-Muslims that grew after the death of Al-Hakam II in 976. Later invasions of stricter Muslim groups led to persecutions of non-Muslims, forcing some (including Muslim scholars) to seek safety in the then still relatively tolerant city of Toledo after its Christian reconquest in 1085.

Spanish society under Muslim rule became increasingly complex, partly because Islamic conquest did not involve the systematic conversion of the much larger conquered population to Islam. At the same time, Christians and Jews were recognized under Islam as "peoples of the book", and so given dhimmi status. Most importantly, the Islamic Berber and Arab invaders were a small minority, ruling over several million Christians. Thus, Christians and Jews were free to practise their religion, but faced certain restrictions and financial burdens. Conversion to Islam proceeded at a steadily increasing pace, as it offered social and economic and political advantages. Merchants, nobles, large landowners, and other local elites were usually among the first to convert. By the 11th century Muslims are believed to have outnumbered Christians in Al-Andalus.

The Muslim community in Spain was itself diverse and beset by social tensions. From the beginning, the Berber people of North Africa had provided the bulk of the armies, clashed with the Arab leadership from the Middle East. The Berbers, who were comparatively recent converts to Islam, resented the aristocratic pretensions of the Arab elite. They soon gave up attempting to settle the harsh lands of the north of the Meseta Central handed to them by the Arab rulers, and many returned to Africa during a Berber uprising against Arab rule. However, the Berbers later took over power and Muslim Spain fell under the rule of the Almoravid and then the Almohad dynasties, amongst others. Over time the relatively tiny number of Moors gradually increased with immigration and cross marriages. Large Moorish populations grew, most notably in the south in the Guadalquivir river valley, and in the east, along the fertile Mediterranean coastal plain and in the Ebro river valley.

Muslim Spain was wealthy and sophisticated at the height of the Islamic rule. Cordoba was the richest and most sophisticated city in all of Western Europe. It was not until the 12th century that western medieval Christendom began to reach comparable levels of sophistication, and this was due in part to the stimulus coming from Muslim Spain. Mediterranean trade and cultural exchange flourished. Muslims imported a rich intellectual tradition from the Middle East and North Africa, including knowledge of mathematics and science that they helped revive. Crops and farming techniques introduced by the Arabs, led to a remarkable expansion of agriculture, which had been in decline since Roman times. In towns and cities magnificent mosques, palaces, and other monuments were constructed. Outside the cities, the mixture of large estates and small farms that existed in Roman times remained largely intact because Muslim leaders rarely dispossessed landowners. The Muslim conquerors were relatively few in number and so they tried to maintain good relations with their subjects.

The relative social peace and splendour, which was already deteriorating ever since the late 10th century, broke down with the later, stricter, Muslim ruling sects of Almoravids and Almohads.

Roman, Jewish, and Muslim culture interacted in complex ways. A large part of the population gradually adopted Arabic. Arabic was the official language of government. Even Jews and Christians often spoke Arabic, while Hebrew and Latin were frequently written in Arabic script. These diverse traditions interchanged in ways that gave Spanish culture — religion, literature, music, art and architecture, and writing systems - a rich and distinctive heritage. However, as the 11th century drew to a close most of the north and centre of Spain was back under Christian control.

Fall of Muslim rule and Unification

The long period of expansion of the Christian kingdoms, beginning in 722 with the Muslim defeat in the Battle of Covadonga and the creation of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias, only eleven years after the Moorish invasion, is called the Reconquista. As early as 739 Muslim forces were driven out of Galicia, which came to host one of Christianity's holiest sites, Santiago de Compostela. Areas in the northern mountains and around Barcelona were soon captured by Frankish and local forces, providing a base for Spain's Christians. The 1085 conquest of the central city of Toledo largely completed the reconquest of the northern half of Spain.

In 1086 the Almoravids, an ascetic Islamic sect from North Africa, conquered the divided small Moorish states in the south and launched an invasion in which they captured the east coast as far north as Saragossa. By the middle of the 12th century the Almoravid empire had disintegrated. The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 heralded the collapse of the great Moorish strongholds in the south, most notably Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248. Within a few years of this nearly the whole of the Iberian peninsula had been reconquered, leaving only the Muslim enclave of Granada as a small tributary state in the south. Surrounded by Christian Castile but afraid of another invasion from Muslim northern Africa, it clung tenaciously to its isolated mountain splendour for two and half centuries. It came to an end in 1492 when Isabella and Ferdinand captured the southern city of Granada, the last Moorish city in Spain. The Treaty of Granada guaranteed religious tolerance toward Muslims while Spain's Jewish population of over 200,000 people was expelled that year. At Ferdinand's urging the Spanish Inquisition had been established in 1478. With a history of being invaded by three Islamic empires (Ummayad, Almoravid and Almohad), there was a fear that Muslims might assist yet another invasion. Also, Aragonese labourers were angered by landlords' use of Moorish workers to undercut them. A 1499 Muslim uprising, triggered by forced conversions, was crushed and was followed by the first of the expulsions of Muslims, in 1502. The year 1492 was also marked by the discovery of the New World. Isabella I funded the voyages of Christopher Columbus. Ferdinand and Isabella, as exemplars of the Renaissance New Monarchs, consolidated the modernization of their respective economies that had been pursued by their predecessors and enforced reforms that weakened the position of the great magnates against the new centralized crowns. In their contests with the French army in the Italian Wars, Spanish forces under Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba eventually achieved success, against the French knights, thereby revolutionizing warfare. The combined Spanish kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, long vibrant and expansive, emerged as a European great power.

The reconquest from the Muslims is one of the most significant events in Spanish history since the fall of the Roman Empire. Arabic quickly lost its place in southern Spain's life, and was replaced by Castilian. The process of religious conversion which started with the arrival of the moors was reversed from the mid 13th century as the Reconquista was advancing south: as this happened the Muslim population either fled or forcefully converted into Catholicism, mosques and synagogues were converted into churches.

With the union of Castile and Aragón in 1479 and the subsequent conquest of Granada in 1492 and Navarre in 1512, the word Spain (España, in Spanish) began being used only to refer to the new unified kingdom and not to the whole of Hispania (the term Hispania (from which España was originally derived) is Latin and the term Iberia Greek).

From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century

Until the late fifteenth century, Castile and León, Aragón and Navarre were independent states, with independent languages, monarchs, armies and, in the case of Aragon and Castile, two empires: the former with one in the Mediterranean and the latter with a new, rapidly growing one in the Americas. The process of political unification continued into the early 16th century. It was the unification of these separate Iberian empires that became the base of what is now referred to as the Spanish Empire.

By 1512, most of the kingdoms of present-day Spain were politically unified by the crown, although not as a modern, centralized state. In contemporary minds, "Spain" was a geographic term that was more or less synonymous with Iberia, not the present-day state called Spain.

During the 16th century, early Habsburg Spain (i.e. the reigns of Charles V, Philip II) became the most powerful state in Europe. The Spanish Empire covered most territories of South and Central America, Mexico, the south of North America, some of Eastern Asia (including the Philippines), the Iberian peninsula (including the Portuguese empire invaded by the Kingdom of Spain and the Duke of Alba in 1580), southern Italy, Sicily, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. It was the first empire about which it was said that the sun did not set. It was a time of daring explorations by sea and by land, the opening up of new trade routes across oceans, conquests and the beginning of European colonization. Not only did this lead to the arrival of ever increasing quantities of precious metals, spices and luxuries, and new agricultural plants, that had a great influence on the development of Europe, but the explorers, soldiers, sailors, traders and missionaries also brought back with them a flood of knowledge that radically transformed the European understanding of the world, ending conceptions inherited from medieval times. An example of this Renaissance intellectual transformation is to be seen in the influential School of Salamanca.

Of note during the 16th and 17th centuries was the cultural efflorescence now known as the Spanish Golden Age.

The middle and latter 17th century saw a grim decline and stagnation under the drifting leadership of the last Spanish Habsburgs. The lingering, "decline of Spain" after a long period of considerable growth was partly due to its successes in the 15th and 16th centuries that gave rise to the treasure fleets across the Atlantic and the Manila galleons across the Pacific, which, combined with the earlier political, social and military adaptations, made Spain the most powerful nation in Europe from the beginning of the 16th century until the middle of the 17th century.

Inflation in the 16th century, partly caused in Spain's case by the opening of the American silver mines from the mid 16th century, engendered a inflation that undermined Spanish trades and commerce (never very large in the Iberian Peninsula, which wasn't highly populated, thus much of the manufactures and finance were diverted to peripheral parts of the Empire - when related to the Peninsula, that is to say - like Flanders or third countries like The Netherlands, northern Italy and other nearby countries like England or the German speaking States).

The wars defending the Spanish empire against envious European rivals, internal successions and the European wars ( Eighty Years' War and Thirty Years' War) in fighting for the Habsburg's dynastic and religious interests ( Counter Reformation).

The Thirty Years' War must be accounted as an on and off but almost continuous conflict which drained Spanish resources into war in Central Europe thus heavily burdening the Empire's economy. A steep economic and demographic decline in the Empire's overly burdened and plague ridden lynchpin (Castile), vast grants of land to the Church and the Habsburg's restoration of power to a self-serving nobility, also undermined the empire.

Reasons for this war were both dynastic and religious. It should be stressed at this point, for a better understanding of the phenomenon, that the moral commitment of the Spanish Empire to the Catholic Church by that time was total and the Spanish Kings often waged war more in terms of genuine faith against the rising Protestantism rather than based in any national interest.

A fog of officially sanctioned orthodoxy gradually smothered a once vibrant and diverse intellectual life. The resentment of ordinary peasants and labourers found expression in implicating the nobility of Moorish ancestry and the churchmen of hypocrisy. The growing beggary forced many to live by their wits, increasing the popularity of picaresque literature. This 17th century stagnation was mirrored throughout Europe, as the growing global oceanic trade that had been pioneered by the Iberian countries, was increasingly diverted to North-Western Europe.

Controversy over succession to the throne consumed what had become an essentially leaderless country with a vast empire, and much of Europe, during the first years of the 18th century.

It was only after this war ended and a new dynasty—the French Bourbons—was installed that a true Spanish state was established when the absolutist first Bourbon king Philip V of Spain in 1707 dissolved the pro-parliamentary Aragon court and unified the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon into a single, unified Kingdom of Spain, abolishing many of the regional privileges and autonomies ( fueros) that had hampered Habsburg rule. The British abandoned the conflict after Utrecht (1713), which led to Barcelona's easy defeat by the " absolutists" in 1714. The National Day of Catalonia still commemorates this defeat.

Following the wars at its commencement the 18th century saw a long, slow recovery, with an expansion of the iron and steel industries in the Basque Country, a growth in ship building, some increase in trade and a recovery in food production and a gradual recovery of population in Castile. The new Bourbon monarchy drew on the French system in trying to modernize the administration and economy, in which it was more successful in the former than the latter. In the last two decades of the century, with the ending of Cadiz's royally granted monopoly, trade experienced rapid growth and even witnessed the initial steps of an industrialization of the textile industry in Catalonia. Spain's effective military assistance to the rebellious British colonies in the American War of Independence won it renewed international standing.

The early nineteenth century

The reformatory efforts of Charles III and his ministers led to a profound gap between partisans of the Enlightenment ( Afrancesados) and the partisans of the Old Spain. The subsequent war with France in 1793 ( French Revolutionary Wars) polarized the country in an apparent reaction against the Gallicised elites. The disastrous Spanish economic situation and the controversial relations with the juggernaut that was Napoleonic France led to the Mutiny of Aranjuez on March 17th 1808 and forced the abdication of the king in favour of Joseph Bonaparte. The abdication was masterminded by Napoleon, who distrusted the uncertain ally that was Spain under the House of Bourbon. The new foreign monarch was regarded with scorn. In May 2, 1808, the people of Madrid rose in arms in a nationalist uprising against the French army. A massively destructive and savagely cruel war known to the Spanish as the War of Independence and to the English as the Peninsular War followed. Napoleon was forced to personally intervene, bringing the Spanish army to its knees and driving the Anglo-Portuguese forces out, but triggering a massive guerrilla war as a result. The guerrillas and Wellington's Anglo-Portuguese army were effective, their actions, combined with Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, led to the ousting of the French from Spain in 1814, and the return of king Ferdinand VII.

Consequences of the Napoleonic rule in Spain

The French invasion had numerous consequences for Spain. The war proved disastrous for Spain's economy, reversing the improvements of the late 18th century. It also brought a political and territorial legacy, but would also leave a deeply divided country prone to great political instability for over a century. In 1812, the Liberal Courts of Cádiz redacted a Constitution, bringing to the country a new form of government, and one by which future monarchs would have to rule, more or less willingly. The power vacuum between 1808 and 1814 had enabled local juntas in the Spanish colonies in America to rule independently. Starting as early as 1809, the continent started freeing itself from Spanish rule; by 1825 with the exceptions of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, and a number of tiny Pacific Islands, Spain had lost all its colonies in Latin America.

Spanish-American War

At the end of the 19th century, Spain lost all of its remaining old colonies in the Caribbean and Asia-Pacific regions, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Philippines, and Guam to the United States after unwittingly and unwillingly being thrust into the Spanish-American War of 1898. In 1899 Spain sold its remaining Pacific possessions to Germany.

"The Disaster" of 1898, as the Spanish-American War was called, gave increased impetus to Spain's cultural revival ( Generation of '98) in which there was much critical self examination, and relieved it from the burden of its last major colonies. However, political stability in such a dispersed and variegated land, caught between pockets of modernity and large areas of extreme rural backwardness and strongly differentiated regional identities and deep divisions over legitimacy originating from the Napoleonic period, would elude the country for some decades yet, and was ultimately imposed only by a brutal dictatorship in 1939.

The 20th century

The 20th century initially brought little peace; Spain played a minor part in the scramble for Africa, with the colonization of Western Sahara, Spanish Morocco and Equatorial Guinea. However the area assigned to Spain was mostly abrupt terrain populated by warlike tribesmen with an age-old history of fighting outsiders. A poorly planned and led advance into the interior due to political pressure led to military disaster in Morocco in 1921. This contributed to discrediting the monarch and worsened political instability. A period of dictatorial rule under General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–1931) ended with the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic. The Republic offered political autonomy to the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia (where the autonomy did not have any effect due to the civil war) and gave voting rights to women.

In the elections in February 1936, the left-wing coalition Popular Front won a narrow victory over the right-wing National Front coalition, but tension continued to mount with the destruction of Church property and an increasing number of politically-motivated murders, including that of prominent right-wing leader José Calvo Sotelo. In July, a number of generals attempted a military takeover that they had been planning for months. The coup failed to topple the government and the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) ensued. After nearly three years of bitter struggle, Nationalist forces led by General Francisco Franco emerged victorious with the support of Germany and Italy. The Republican side was supported by the Soviet Union and Mexico, but was crucially left isolated through the British-led policy of Non-Intervention. The Spanish Civil War has been called the first battle of the Second World War. Spanish involvement in the Second World War was in fact a continuation of its civil war, as the ideological conflicts involved had much in common (but also some important differences), despite Franco's official policy of neutrality and non-belligerency during the years of Axis success. In 1940, Francisco Franco and his brother-in-law, the foreign minister, Ramón Serrano Súñer, met Adolf Hitler in Hendaye (then in German-occupied France) to discuss Spanish participation in World War II as part of the Axis. This short trip across the border was the only time Franco left Spain during his long dictatorship. No agreement was reached and Spain remained neutral though sympathetic.

Over a hundred thousand highly motivated Spanish Civil War veterans were to give both sides the benefit of their experience throughout the Second World War in Europe, the Eastern Front and North Africa. A number of the most effective forces in the French Resistance were Spanish as was the 9th Armoured Company that spearheaded Général Leclerc's 2nd Armoured Division's liberation of Paris. On the other side, about 40,000 Spaniards fought against the Soviet Union in the Wehrmacht's División Azul ( Blue Division).

The only legal party under Franco's regime was the Falange española tradicionalista y de las JONS formed in 1937 by the forcible fusion of the pseudo-fascist Falange and the monarchist Carlist movement. The party emphasized anti-Communism, Catholicism, nationalism, and imperial expansion and was one of the regime's major instruments of internal control.

After World War II, being one of few surviving authoritarian regimes in Western Europe, Spain was politically and economically isolated and was kept out of the United Nations until 1955, when it became strategically important for US president Eisenhower to establish a military presence in the Iberian peninsula. Eisenhower, signed a treaty with Franco in 1953 to build the military air base in Torrejón de Ardoz (this base had nuclear weapons) some 20km east of Madrid, the naval base of Rota, Cádiz (also with nuclear weapons in submarines), and the air bases of Morón de la Frontera, Seville, and Zaragoza. Franco’s opposition to Communism aided this opening to Spain. In the 1960s, Spain began to enjoy economic growth ( Spanish miracle) which gradually transformed it into a modern industrial economy with a thriving tourism sector. Growth continued well into the 1970s, with Franco's government going to great lengths to shield the Spanish people from the effects of the oil crisis.

Upon the death of General Franco in November 1975, his personally designated heir Prince Juan Carlos assumed the position of king and head of state. With the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978 and the arrival of democracy, some regions — Basque Country, Navarra— were given complete financial autonomy, and many — Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia and Andalusia— were given some political autonomy, which was then soon extended to all Spanish regions, resulting in what is regarded as the most decentralized territorial organization in Western Europe. In the Basque Country, moderate Basque nationalism coexists with radical nationalism supportive of the terrorist group ETA.

On January 1, 1999 Spain adopted the Euro as its national currency.

Ever since the current Constitution was passed in 1978, Spain has had 5 Presidentes del Gobierno (Prime Ministers) as of September 2006: Adolfo Suárez González (1977-1981) who won the election for the Unión de Centro Democrático ( UCD, now extinct), Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo Bustelo (1981-1982) also for the UCD (under his presidency there was an attempted coup d'état on 23 February 1981), Felipe González Márquez (1982-1996) who won four consecutive elections heading the Partido Socialista Obrero Español ticket ( PSOE), during his administrations Spain joined NATO and European Union) and then José María Aznar López (1996-2004) who won two consecutive elections for the Partido Popular (PP). Last in this list is current Presidente del Gobierno José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero ( 2004-Incumbent) again for the PSOE.

21st Century

In November 2002, the oil tanker Prestige sank near to the Galician coast, causing a huge oil spill. It has since been regarded as one of the worst environmental disasters in Spanish history.

On March 11 2004, a series of bombs exploded in commuter trains in Madrid, Spain. This act of terror killed 191 people and wounded 1,460 more, besides having a dramatic effect on the upcoming national elections. The 11 March 2004 Madrid train bombings had an adverse effect on the then-ruling conservative party Partido Popular (PP) which polls were giving as a likely winner of the elections, thus helping the election of Zapatero's Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). There were two nights of incidents around the PP headquarters, with PSOE accusing the PP of hiding the truth by saying that the incidents were caused by ETA. These incidents are still a cause of discussion, since some factions of the PP suggest that the elections were "stolen" by means of the turmoil which followed the terrorist bombing, which was, according to this point of view, backed or fuelled by the PSOE. These incidents did interfere with the last day of campaigning when, according to the Spanish electoral system regulations, any kind of political propaganda is prohibited and PP's candidate ( Mariano Rajoy) appeared in some newspapers as interior minister.

March 14 2004 saw the PSOE party elected into government, with Zapatero becoming the new PM of Spain. Since the PSOE's election victory Zapatero's government has withdrawn Spanish troops from Iraq and legalized same-sex marriages. He also presided over the Spanish Parliament's approval of the new (and controversial) Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia. Spain has experienced increasing immigration since the start of the twenty-first century.

Politics

Spain is a constitutional monarchy, with a hereditary monarch and a bicameral parliament, the Cortes Generales. The executive branch consists of a Council of Ministers presided over by the President of Government (comparable to a prime minister), proposed by the monarch and elected by the National Assembly following legislative elections.

The legislative branch is made up of the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados) with 350 members, elected by popular vote on block lists by proportional representation to serve four-year terms, and a Senate or Senado with 259 seats of which 208 are directly elected by popular vote and the other 51 appointed by the regional legislatures to also serve four-year terms.

Spain is, at present, what is called a State of Autonomies, formally unitary but, in fact, functioning as a highly decentralized Federation of Autonomous Communities, each one with slightly different levels of self-government. The little differences within this system are due to the fact that the devolution process from the centre to the periphery was a process initially thought to be asymmetrical, granting a higher degree of self government only to those autonomous governments ruled by nationalist parties (namely Catalonia and the Basque Country) who were much more vocal in the matter and seeking a more federalist kind of relationship with the rest of Spain. Conversely the rest of Autonomous Communities would have a lower self-government. This pattern of asymmetrical devolution has been described as a coconstitutionalism and the devolution process adopted by the United Kingdom since 1997 shares traits with it.

However, as years passed, the Autonomous Communities which in the beginning were thought to have a lower profile have caught up in terms of self-government with the nationalist ruled Autonomous communities and the gap in terms of self-government is not that wide anymore.

In the end, Spain is regarded as probably the most decentralized State in Europe at the present moment, with all of its different territories managing locally their Health and Education systems (just to mention some aspects of the public budget) and with some other territories (the Basque Country and Navarre) even managing their own public finances without hardly any presence of the Spanish central government in this regard or, in the case of Catalonia and the Basque Country, equipped with their own, fully operative and completely autonomous, police corps which widely replaces the State police functions in these territories (see Mossos d'Esquadra and Ertzaintza).

The Government of Spain has been involved in a long-running campaign against Basque Fatherland and Liberty ( ETA), a terrorist organization founded in 1959 in opposition to Franco and dedicated to promoting Basque independence through violent means. They consider themselves a guerrilla organization while they are actually listed as a terrorist organization by both the European Union and the United States in their watchlists on the matter. Although the current nationalist led Basque Autonomous government does not endorse any kind of violence, their different approaches as to how to terminate ETA and their different approaches to the separatist movement are a source of tension between the central and Basque governments.

Initially ETA targeted primarily Spanish security forces, military personnel and Spanish Government officials. As the security forces and prominent politicians improved their own security, ETA increasingly focused its attacks on the tourist seasons (scaring tourists was seen as a way of putting pressure on the government, given the sector's importance to the economy, although no tourists were injured) and local government officials in the Basque Country. The group carried out numerous bombings against Spanish Government facilities and economic targets, including a car bomb assassination attempt on then-opposition leader Aznar in 1995, in which his armored car was destroyed but he was unhurt. The Spanish Government attributes over 800 deaths to ETA during its campaign of rebellion.

On 17 May 2005, all the parties in the Congress of Deputies, except the PP, passed the Central Government's motion giving approval to the beginning of peace talks with ETA, without making political concessions and with the requirement that it give up its weapons. PSOE, CiU, ERC, PNV, IU-ICV, CC and the mixed group —BNG, CHA, EA y NB— supported it with a total of 192 votes, while the 147 PP parliamentarians objected. ETA declared a "permanent cease-fire" that came into force on March 24, 2006. In the years leading up to the permanent cease-fire, the government had had more success in controlling ETA, due in part to increased security cooperation with French authorities.

On February 20 2005, Spain became the first country to allow its people to vote on the European Union constitution that was signed in October 2004. The rules state that if any country rejects the constitution then the constitution will be declared void. Despite a very low participation (42%), the final result was very strongly in affirmation of the constitution, making Spain the first country to approve the constitution via referendum (Hungary, Lithuania and Slovenia approved it before Spain, but they did not hold referenda).

Geography

Mainland Spain is dominated by high plateaus and mountain ranges such as the Pyrenees or the Sierra Nevada. Running from these heights are several major rivers such as the Tajo, the Ebro, the Duero, the Guadiana and the Guadalquivir. Alluvial plains are found along the coast, the largest of which is that of the Guadalquivir in Andalusia, in the east there are alluvial plains with medium rivers like Segura, Júcar and Turia. Spain is bound to the south and east by Mediterranean Sea (containing the Balearic Islands), to the north by the Cantabrian Sea and to its west by the Atlantic Ocean, where the Canary Islands off the African coast are found.

Due to Spain's own geographical situation which allows only its northern part to be in the way of the Jet Stream's typical path and due to its own orographic conditions, its climate is extremely diverse. It can be roughly divided in the following areas:

- The Northern and Eastern Mediterranean coast (Catalonia, Northern half of the Land of Valencia and the Balearic islands): Warm to hot summers with relatively mild to cool winters. Precipitation averaging 600mm (23.6 in) a year. These show an average Mediterranean climate.

- The South East Mediterranean coast (Alicante, Murcia and Almería): Hot summers and mild to cool winters. Very dry, virtually sub-desertic, rainfall as low as 150mm (5.9 in) a year in the Cabo de Gata which is reported to be the driest place in Europe. These areas qualify mostly as Semiarid climate in terms of precipitation.

- Southern Mediterranean coast (Málaga area and Granada's coastal part): Warm summers, very mild winters. Average yearly temperatures close to 20 degrees Celsius (68 °F) and wet. Close to Subtropical climate.

- The Guadalquivir valley (Seville, Cordoba): Very hot and dry summers and mild winters. Relatively dry climate.

- South West Atlantic coast (Cadiz, Huelva): Pleasant summers, very mild and temperate winters. Relatively wet climate.

- The inner land plateau: Cold winters (depending mostly on altitude) and hot summers, close to the Continental climate. Relatively dry weather (400-600mm or 15.7 - 23.6 in per year).

- Ebro Valley (Zaragoza): Very hot summers, cold winters. Also close to the Continental climate. Dry in terms of precipitations.

- Northern Atlantic coast or " Green Spain" (Galicia, Asturias, Coastal Basque country): A very wet climate (averaging 1000mm. or 39.4 in a year, some spots over 1200mm. or 47.2 in), with mild summers and mild to cool winters. These show mostly an Oceanic climate.

- The Pyrenees: overall wet weather with cool summers and cold winters, the highest part of it has an Alpine climate.

- The Canary Islands: Subtropical climate in terms of temperature, being these mild and stable (18 °C to 24 °C; 64 °F to 75 °F) throughout the year. Desertic in the Eastern islands and moister in the westernmost ones. According to a study carried out by Thomas Whitmore, director of research on climatology at the Syracuse University (USA), the city of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria enjoys the best climate in the world.

At 194,884 mi² (504,782 km²), Spain is the world's 51st-largest country (after Thailand). It is comparable in size to Turkmenistan, and somewhat larger than the US state of California.

| Location | Record highs | Record lows | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (° C) | (° F) | (° C) | (° F) | |

| Mediterranean | ||||

| Murcia | 47.2°C | 117.0°F | −6.0°C | 21.2°F |

| Malaga | 44.2°C | 111.6°F | −3.8°C | 25.1°F |

| Valencia | 42.5°C | 108.5°F | −7.2°C | 19°F |

| Alicante | 41.4°C | 106.5°F | −4.6°C | 23.7°F |

| Palma of Mallorca | 40.6°C | 105.1°F | - | - |

| Barcelona | 39.8°C | 103.6°F | −10.0°C | 14°F |

| Girona | 41.7 | 107°F | −13.0°C | 8.6°F |

| The inner land | ||||

| Sevilla | 47.0°C | 116.6°F | −5.5°C | 22.1°F |

| Cordoba | 46.6°C | 115.9°F | - | - |

| Badajoz | 45.0°C | 113°F | - | - |

| Albacete | 42.6°C | 108.7°F | −24.0°C | −11.2°F |

| Zaragoza | 42.6°C | 108.7°F | - | - |

| Madrid | 42.2°C | 108.0°F | −14.8°C | 5.4°F |

| Burgos | 41.8°C | 107.2°F | −22.0°C | −7.6°F |

| Valladolid | 40.2°C | 104.4°F | - | - |

| Salamanca | - | - | −20.0°C | −4.0°F |

| Teruel | - | - | −19.0°C | −2.2°F |

| Northern Atlantic coast | (° C) | (° F) | (° C) | (° F) |

| Ourense | 45°C | 113°F | −9.0°C | 58.2°F |

| Bilbao | 42.0°C | 107.6°F | −8.6°C | 16.5°F |

| La Coruña | 37.6°C | 99.7°F | −4.8°C | 23.4°F |

| Gijón | 36.4°C | 97.5°F | −4.8°C | 23.4°F |

| The Canary Islands | ||||

| Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | 38.6°C | 102°F | 11.4 ° | 48.6°F |

Territorial disputes

Territories claimed by Spain

Spain has called for the return of Gibraltar, a small but strategic British overseas territory which lies near the Peninsula's southernmost tip, in the Eastern side of the Strait of Gibraltar. It was conquered during the War of the Spanish Succession in 1704 and was ceded to Britain in perpetuity in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. An overwhelming majority of Gibraltar's 30,000 inhabitants want to remain British, as they have repeatedly proven in referenda on the issue. The UN resolutions (2231 (XXI) and 2353 (XXII)) call on the UK and Spain to reach an agreement to resolve their differences over Gibraltar, while Spain does not recognize this border and so it is ordinarily kept under strict traffic scrutiny (in the recent past it was often closed as a means to put pressure to Gibraltar, since its economy is partially dependent on Spanish goods and workers which arrive there from the Spanish side).

Moreover, the exact tracing of the demarcation line established by the Treaty of Utrecht is disputed between both sides (Spain claims that the UK is also occupying a tract of land around the airport which was not originally included in the Treaty provisions).

Gibraltar is officially a non-self governing territory or colony according to the UN original definition; in this regard, article 103 of the UN Charter states, universally speaking, that the right of self-determination of the people from the non-self governing territory should be the paramount and overriding principle. To this, the Spanish position objects that it would overrule the only legal document available on the matter, the Treaty of Utrecht, which states that the area must return to Spain should the UK renounce to it.

Spanish territories claimed by other countries

Morocco claims the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla and the Vélez, Alhucemas, Chafarinas, and Perejil islands, all on the Northern coast of Africa. Morocco points out that those territories were obtained when Morocco could not do anything to prevent it and has never signed treaties ceding them, but Morocco did not yet exist in the 14th and 15th century when these places became Spanish possessions. Spain claims that these territories are integral parts of Spain and have been Spanish or linked to Spain since before the Islamic invasion of Spain in 711; the Ceuta area (including the islet of Perejil) returned to Spanish rule in 1415 and the rest did so only a few years after the conquest of Granada in 1492. Spain claims that Morocco's only claim on these territories is merely geographical. Parallelism with Egyptian ownership of the Sinai (in Asia) or Turkish ownership of Istanbul (in Europe) is often used to support the Spanish position.

Portugal does not recognize Spain's sovereignty over the territory of Olivenza. The Portuguese claim that the Treaty of Vienna (1815), to which Spain was a signatory, stipulated return of the territory to Portugal. Spain alleges that the Treaty of Vienna left the provisions of the Treaty of Badajoz (1801) intact.

Economy

Spain's mixed economy supports a GDP that on a per capita basis is 87% of that of the four leading West European economies. The centre-right government of former Prime Minister Aznar worked successfully to gain admission to the first group of countries launching the European single currency, the euro, on 1 January 1999. The Aznar administration continued to advocate liberalization, privatization, and deregulation of the economy and introduced some tax reforms to that end. Unemployment fell steadily both under the Aznar and Zapatero administration. It affects now 7.6% of the labor force (October 2006) having fallen from a high of 20% and above in the early 1990s. It also compares favourably to the other large European countries, most notably, Germany with an unemployment of approximately 12%. Growth of 2.4% in 2003 was satisfactory given the background of a faltering European economy, and has steadied since at an annualized rate of about 3.3% in mid 2005 and 3.5% in the first quarter and 3,7% in the second quarter of 2006. There is a widespread concern, however, that the growth is too concentrated upon a few sectors (mainly residential building and those related to it). The current Prime Minister Rodríguez Zapatero has pointed out as matters to be addressed during his administration plans to reduce government intervention in business, combat tax fraud, and support innovation, research and development, but also intends to reintroduce labour market regulations that had been scrapped by the Aznar government. Adjusting to the monetary and other economic policies of an integrated Europe — and reducing unemployment — will pose challenges to Spain over the next few years. According to World Bank GDP figures from 2005, Spain has the ninth largest economy in the world, after Canada, and the fifth largest in Europe, after Italy.

There is general concern that Spain's model of economic growth (based largely on mass tourism, the construction industry, and manufacturing sectors) is faltering and may prove unsustainable over the long term. The first report of the Observatory on Sustainability (Observatorio de Sostenibilidad) — published in 2005 and funded by Spain's Ministry of the Environment and Alcalá University — reveals that the country's per capita GDP grew by 25% over the last ten years, while greenhouse gas emissions have risen by 45% since 1990. Although Spain's population grew by less than 5% between 1990 and 2000, urban areas expanded by no less than 25% over the same period. Meanwhile, Spain's energy consumption has doubled over the last 20 years and is currently rising by 6% per annum. This is particularly worrying for a country whose dependence on imported oil (meeting roughly 80% of Spain's energy needs) is one of the greatest in the EU. Large-scale unsustainable development is clearly visible along Spain's Mediterranean coast in the form of housing and tourist complexes, which are placing severe strain on local land and water resources. Recent developments include the construction of reverse osmosis plants along the Spanish Costas, to probably meet over 1% of Spain's total water needs. Other perennial weak points of Spain's economy include one of the lowest rates of investment in Research and Development, and in education in the EU. This is particularly worrying, given that the country's generally poorly-trained workforce is no longer as competitive in price terms as it was several decades ago. As a result, many manufacturing jobs are going abroad — mainly to Eastern Europe and Asia.

On the brighter side, the Spanish economy is credited for having avoided the virtual zero growth rate of some of its largest partners in the EU (namely France and Germany) by the late 90's and beginning of the 21st century in a process which started with former Prime Minister Aznar's liberalization and deregulation reforms aiming to reduce the State's role in the market place. Thus, in 1997 Spain started an economic cycle -which keeps going as of 2006- marked by an outstanding economic growth, with figures around 3%, often well over this rate.

This has narrowed steadily the economic gap between Spain and its leading partners in the EU over this period. Hence, the Spanish economy has been regarded lately as one of the most dynamic within the EU, even able to replace the leading role of much larger economies like the aforementioned, thus subsequently attracting significant amounts of foreign investment.

Demographics

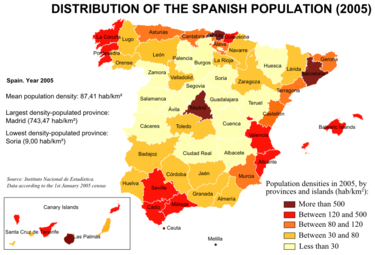

Spain's population density, at 87.8/km² (220/sq. mile), is lower than that of most Western European countries and its distribution along the country is very unequal. With the exception of the region surrounding the capital, Madrid, the most populated areas lie around the coast.

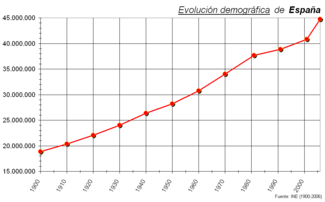

The population of Spain doubled during the twentieth century, due to the spectacular demographic boom by the 60's and early 70's. Then, after the birth rate plunged in the 80's and Spain's population became stalled, a new population increase started based initially in the return of many Spanish who emigrated to other European countries during the 70's and, more recently, it has been boosted by the large figures of foreign immigrants, mostly from Latin America (38.75% of them), Eastern Europe (16.33%), Maghreb (14.99%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (4.08%). Also some important pockets of population coming from other countries in the European Union are found (20.77% of the foreign residents), specially along the Mediterranean costas and Balearic islands, where many choose to live their retirement or even telework. However, the pattern of growth was extremely uneven due to large-scale internal migration from the rural interior to the industrial cities during the 60's and 70's. No fewer than eleven of Spain's fifty provinces saw an absolute decline in population over the century.

Immigration in Spain

According to the Spanish government there were 3.7 million foreign residents in Spain in 2005; independent estimates put the figure at 4.8 million or 11.1% of total population (Red Cross, World Disasters Report 2006). According to residence permit data for 2005, around 500,000 were Moroccan, another half a million were Ecuadorian, more than 200,000 were Romanians and 270,000 were Colombian. Other important foreign communities are British (6.09% of all the foreign residents), Argentine (6.10%), German (3.58%) and Bolivian (2.63%). In 2005, a regularization programme increased the legal immigrant population by 700,000 people. Since 2000 Spain has experienced high population growth as a result of immigration flows, despite a birth rate that is only half of the replacement level. This sudden and ongoing inflow of immigrants, particularly those arriving clandestinely by sea, has caused noticeable social tensions.

Spain currently is thought to have one of the highest immigration rates within the EU. This can be explained by a number of reasons including its geographical position, the porosity of its borders, the large size of its submerged economy and the strength of the agricultural and construction sectors which demand more low cost labour than can be offered by the national workforce.

On the other hand mass immigration has put downward pressure on the wages of Spanish born workers in construction and agriculture and in a number of service sector jobs at a time of soaring house and rental costs. This could aggravate social tensions in the event of economic deceleration.

Most populous metropolitan regions

- Madrid 5,646,572

- Barcelona 3,135,758

- Valencia 1,623,724

- Sevilla 1,317,098

- Málaga 1,074,074

- Bilbao 946,829

Identities

The Spanish Constitution of 1978, in its second article, recognizes historic entities ("nationalities“, a carefully chosen word in order to avoid the more politically loaded "nations") and regions, inside the unity of the Spanish nation. However, Spain's identity is for some people more an overlap of different regional identities than a sole Spanish identity. Indeed, some of the regional identities may be even in conflict with the Spanish one.

In particular, a large proportion of Catalans, Basques and Galicians, quite frequently identify, respectively, primarily with Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia, with Spain only second or not at all. For example, according to the last CIS survey, 44% of Basques identify themselves first as Basques (only 8% first as Spaniards); 40% of Catalans do so with Catalonia (20% identify firstly with Spain), and 32% Galicians with Galicia (9% with Spain).

Almost all communities have a majority of people identifying as much with Spain as with the Autonomous Community (except Madrid, where Spain is the primary identity, and Catalonia, Basque Country, Galicia, and the Balearics, where people tend to identify more with their Autonomous Community). It is this last feature of "shared identity" between the more local level or Autonomous Community and the Spanish level which makes the identity question in Spain complex and far from univocal.

Languages

The Spanish Constitution, although affirming the sovereignty of the Spanish Nation, recognizes historical nationalities.

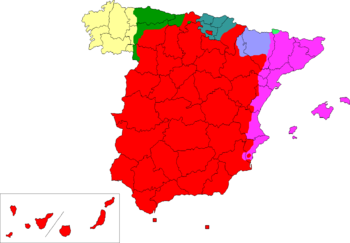

Castilian (called both español and castellano in the language itself) is an official language throughout Spain, but other regional languages are also spoken, and are the primary languages in some of their respective geographies. Without mentioning them by name, the Spanish Constitution recognizes the possibility of regional languages being co-official in their respective autonomous communities. The following languages are co-official with Spanish according to the appropriate Autonomy Statutes.

- Catalan (català) in Catalonia (Catalunya), the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears), parts of Valencia (València) (as Valencian)

- Basque (euskara) in Basque Country (Euskadi or País Vasco), and parts of Navarre (Nafarroa or Navarra). Basque is not known to be related to any other language.

- Galician (galego) in Galicia (Galicia or Galiza) and the occidental borders of Asturias and Leon.

- Occitan (the Aranese dialect). Spoken in the Val d'Aran in Catalonia.

Catalan, Galician, Aranese (Occitan) and Castilian are all descended from Latin and some of them have their own dialects, some championed as separate languages by their speakers. A particular case is Valencian, the name given to a variety of Catalan, that also has the co-official language status recognized in Autonomous Community of Valencia.

There are also some other surviving Romance minority languages: Asturian / Leonese, in Asturias and parts of Leon, Zamora and Salamanca, and the Extremaduran in Caceres and Salamanca, both descendants of the historical Astur-Leonese dialect; the Aragonese or fabla in part of Aragon; the fala, spoken in three villages of Extremadura; and some Portuguese dialectal towns in Extremadura and Castile-Leon. However, unlike Catalan, Galician, and Basque, these do not have any official status.

In the tourist areas of the Mediterranean costas and the islands, German and English are widely spoken by tourists, foreign residents and tourism workers. On the other side, recent African immigrants and large minority of their descendants speaks the official European languages of their homelands (whether standard Portuguese, English, French, or its Creoles.)

Minority groups

Since the 16th century, the most famous minority group in the country have been the Gitanos, a Roma group.

Spain harbours a number of black African-blooded people — who are descendants of populations from former colonies (especially Equatorial Guinea) but, much more important than those in numbers, immigrants from several Sub-Saharan and Caribbean countries who have been recently settling in Spain. There are also sizeable numbers of Asian-Spaniards, most of whom are Chinese, Filipino, Middle Eastern, Pakistani and Indian origins; Spaniards of Latin American descent are sizeable as well and a fast growing segment.

The important Jewish population of Spain was either expelled or forced to convert in 1492, with the dawn of the Spanish Inquisition. After the 19th century, some Jews have established themselves in Spain as a result of migration from former Spanish Morocco (actually Melilla enjoys the highest ratio of Jews in Spain), escape from Nazi repression and immigration from Argentina. The Spanish law allows Sephardi Jews to claim Spanish citizenship.

A sizeable and increasing number of Spanish citizens also descend from these communities, as Spain applies jus soli and provides special measures for immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries to obtain Spanish citizenship.

Religion

Roman Catholicism is the most popular religion in the country. According to several sources (CIA World Fact Book 2005, Spanish official polls and others), from 94% to 81% self-identify as Catholics, whereas around 6% to 19% identify with either other religions or none at all. It is important to note, however, that many Spaniards identify themselves as Catholics just because they were baptized, even though they may not be very religious.

Evidence of the secular nature of contemporary Spain can be seen in the widespread support for the legalization of same-sex marriage in Spain — over 70% of Spaniards support gay marriage according to a 2004 study by the Centre of Sociological Investigations. Indeed, in June 2005 a bill was passed by 187 votes to 147 to allow gay marriage, making Spain the third country in the European Union to allow same-sex couples to marry. This vote was split along conservative-liberal lines, with PSOE and other left-leaning parties supporting the measure and PP against it. Proposed changes to the divorce laws to make the process quicker and to eliminate the need for a guilty party are also popular.

There are also many Protestant denominations, all of them with less than 50,000 members, and about 20,000 Mormons. Evangelism has been better received among Gypsies than among the general population; pastors have integrated flamenco music in their liturgy. Taken together, all self-described "Evangelicals" slightly surpass Jehovah's Witnesses (105,000) in number. Other religious faiths represented in Spain include the Bahá'í Community.

The recent waves of immigration, especially during and after the 90's, have led to an increasing number of Muslims, who have about 1 million members. Muslims had ceased to live in Spain for centuries, ever since the Reconquista, when they were given the ultimatum of either convert to Catholicism or leave the country. By the 16th century, most of them had left the Spanish kingdom. However, the colonial expansion over Northern and Western Africa during the 19th and 20th centuries supposed that large numbers of Muslim populations (those in the Spanish Morocco and the Sahara Occidental) were again under Spanish administration, with a minority of them getting full citizenship. Nowadays, Islam is the second largest religion in Spain, after Roman Catholicism, accounting for approximately 3% of the total population. Hindus and Sikhs account for less than 0.3%.

Since the expulsion of the Sephardim in 1492, Judaism was practically nonexistent until the 19th century, when Jews were again permitted to enter the country. Currently there are around 50,000 Jews in Spain, all arrivals in the past century and accounting less than 1% of the total number of inhabitants. There are also many Spaniards (in Spain and abroad) who claim Jewish ancestry to the Conversos, and still practise certain customs. Spain is believed to have been about 8% Jewish on the eve of the Spanish Inquisition.

Over the past thirty years, Spain has become a more secularized society as the number of believers has decreased significantly. For those who do believe, the degree of accordance and practice to their religion is diverse.

International rankings

- Reporters Without Borders world-wide press freedom index 2002: Rank 40 out of 139 countries.

- The Economist Intelligence Units worldwide quality-of-life index 2005: Rank 10 out of 111 countries (above countries like the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and France)

- Nation Master's list by economic importance: Rank 9 of 25 countries, only surpassed by G-8 members (except Russia) and Australia.

- Nation Master's list by technological achievement: Rank 18 of 68 countries.

Neighbouring countries

|

North Atlantic Ocean | Bay of Biscay |  |

|

| Balearic Sea | ||||

North Atlantic Ocean |

Strait of Gibraltar |

Mediterranean Sea |

Other images

|

The Sagrada Familia by night, Barcelona

|

|||

|

Aran valley, Catalonia

|