Latin alphabet

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Linguistics

| Latin alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type: | Alphabet | |

| Languages: | Latin and Romance languages; most languages of Europe; Romanizations exist for practically all known languages. | |

| Time period: | ~700 B.C. to the present | |

| Parent writing systems: | Proto-Canaanite alphabet Phoenician alphabet Greek alphabet Old Italic alphabet Latin alphabet |

|

| Sister writing systems: | Cyrillic Coptic Runic/Futhark |

|

| Unicode range: | See Unicode Latin | |

| ISO 15924 code: | Latn | |

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. See IPA chart for English for an English-based pronunciation key. | ||

| History of the Alphabet |

|---|

|

Middle Bronze Age 19–15th c. BC

|

| Meroitic 3rd c. BC |

| Complete genealogy |

The Latin alphabet, also called the Roman alphabet, is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world today. Apart from Latin itself, the alphabet was adapted to the direct descendants of Latin (the Romance languages), Germanic, Celtic and some Slavic languages from the Middle Ages, and finally to most languages of Europe. With the age of colonialism and Christian proselytism, the alphabet was spread overseas, and applied to Austronesian languages, Vietnamese, Hausa, Swahili, Tagalog and many others.

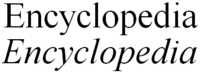

In modern usage, the term Latin alphabet is used for any straightforward derivation of the alphabet used by the Romans. These variants may drop letters (e.g. the Italian alphabet) or add letters (e.g. the Danish alphabet) to or from the classical Roman script, and of course many letter shapes have changed over the centuries — such as the lower-case letters which the Romans would not have recognized. The Latin alphabet evolved from the Greek alphabet which is based upon the Phoenician alphabet.

Evolution

| A | B | C | D | E | F | Z |

| H | I | K | L | M | N | O |

| P | Q | R | S | T | V | X |

It is generally held that the Latins adopted the western variant of the Greek alphabet in the 7th century BC from Cumae, a Greek colony in southern Italy. Roman legend credited the introduction to one Evander, son of the Sibyl, supposedly 60 years before the Trojan war, but there is no historically sound basis to this tale. From the Cumae alphabet, the Etruscan alphabet was derived and the Latins finally adopted 21 of the original 26 Etruscan letters.

Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the Z was dropped and a new letter G was placed in its position. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters was short-lived, but after the conquest of Greece in the first century BC the letters Y and Z were, respectively, adopted and readopted from the Greek alphabet and placed at the end. Now during the classical Latin period, the alphabet contained 23 letters:

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en |

| Latin pronunciation ( IPA) | /aː/ | /beː/ | /keː/ | /deː/ | /eː/ | /ef/ | /geː/ | /haː/ | /iː/ | /kaː/ | /el/ | /em/ | /en/ |

| Letter | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ex | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation ( IPA) | /oː/ | /peː/ | /kʷuː/ | /er/ | /es/ | /teː/ | /uː/ | /eks/ | /iː 'graika/ | /'zeːta/ |

The Latin names of some of the letters are disputed. In general, however, the Romans did not use the traditional (Semitic-derived) names as in Greek: the names of the stop consonant letters were formed by adding /eː/ to the sound (except for C, K, and Q which needed different vowels to distinguish them) and the names of the continuants consisted either of the bare sound, or the sound preceded by /e/. The letter Y when introduced was probably called hy /hyː/ as in Greek (the name upsilon being not yet in use) but was changed to i Graeca ("Greek i") as Latin speakers had difficulty distinguishing /i/ and /y/ . Z was given its Greek name, zeta. For the Latin sounds represented by the various letters see Latin spelling and pronunciation; for the names of the letters in English see English alphabet.

Roman cursive script, also called majuscule cursive and capitalis cursive, was the everyday form of handwriting used for writing letters, by merchants writing business accounts, by schoolchildren learning the Roman alphabet, and even emperors issuing commands. A more formal style of writing was based on Roman square capitals, but cursive was used for quicker, informal writing. It was most commonly used from about the 1st century BC to the 3rd century, but it probably existed earlier than that.

Medieval and later developments

It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter J (representing non-syllabic I) and the letters U and W (to distinguish them from V) were added.

The lower case ( minuscule) letters developed in the Middle Ages from New Roman Cursive cursive writing, first as the uncial script, and later as minuscule script. The old capital Roman letters were retained for formal inscriptions and for emphasis in written documents. The languages that use the Latin alphabet generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and for proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalised; whereas Modern English of the 18th century had frequently all nouns capitalised, in the same way that Modern German is today, e.g. "All the Sisters of the old Town had seen the Birds".

Spread of the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet spread from Italy, along with the Latin language, to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Roman Empire, including Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half of the Empire, and as the western Romance languages, including Spanish, French, Catalan, Portuguese and Italian, evolved out of Latin they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet. With the spread of Western Christianity the Latin alphabet spread to the peoples of northern Europe who spoke Germanic languages, displacing their earlier Runic alphabets, as well as to the speakers of Baltic languages, such as Lithuanian and Latvian, and several (non- Indo-European) Finno-Ugric languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian. During the Middle Ages the Latin alphabet also came into use among the peoples speaking West Slavic languages, including the ancestors of modern Poles, Czechs, Croats, Slovenes, and Slovaks, as these peoples adopted Roman Catholicism; the speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted both Orthodox Christianity and the Cyrillic alphabet.

As late as 1492, the Latin alphabet was limited primarily to the languages spoken in western, northern and central Europe. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of eastern and southern Europe mostly used the Cyrillic alphabet, and the Greek alphabet was still in use by Greek-speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic alphabet was widespread within Islam, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Over the past 500 years, the Latin alphabet has spread around the world. It spread to the Americas, Australia, and parts of Asia, Africa, and the Pacific with European colonization, along with the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, and Dutch languages. In the late eighteenth century, the Romanians adopted the Latin alphabet; although Romanian is a Romance language, the Romanians were predominantly Orthodox Christians, and until the nineteenth century the Church used the Cyrillic alphabet. Vietnam, under French rule, adapted the Latin alphabet for use with the Vietnamese language, which had previously used Chinese characters. The Latin alphabet is also used for many Austronesian languages, including Tagalog and the other languages of the Philippines, and the official Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets. In 1928, as part of Kemal Atatürk's reforms, Turkey adopted the Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing the Arabic alphabet. Most of Turkic-speaking peoples of the former USSR, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azeri, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and others, used the Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s. In the 1940s all those alphabets were replaced by Cyrillic. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, several of the newly-independent Turkic-speaking republics adopted the Latin alphabet, replacing Cyrillic. Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan have officially adopted the Latin alphabet for Azeri, Uzbek, and Turkmen, respectively. In the 1970s, the People's Republic of China developed an official transliteration of Mandarin Chinese into the Latin alphabet, called Pinyin, although use of the Pinyin has been very rare outside educational and tourism purposes.

West Slavic and most South Slavic languages use the Latin alphabet rather than the Cyrillic, a reflection of the dominant religion practiced among those peoples. Among these, Polish uses a variety of diacritics and digraphs to represent special phonetic values, as well as the l with stroke - ł - for a sound which was originally the so-called dark L, although it has become similar to w in modern varieties of the language. Czech uses diacritics as in Dvořák — the term háček (caron) originates from Czech. Croatian and the Latin version of Serbian use carons in č, š, ž, an acute in ć and a bar in đ. The languages of Eastern Orthodox Slavs generally use the Cyrillic alphabet instead, which is more closely based on the Greek alphabet. The Serbian language uses the two alphabets.

Extensions

In the course of its use, the Latin alphabet was adapted for use in new languages, sometimes representing phonemes not found in languages that were already written with the Roman characters. To represent these new sounds, extensions were therefore sometimes created. They were made by adding diacritics to existing letters, by joining multiple letters together to make ligatures, by creating completely new forms, or by assigning a special function to pairs or triplets of letters. These new forms are given a place in the alphabet by defining a collating sequence, which is often language-dependent.

Diacritics

A diacritic, in some cases also called an accent mark, is a small symbol which can appear above or below a letter, or in some other position, such as the umlaut mark used in the German symbols Ä, Ö, Ü. Its main usage is to change the phonetic value of the letter to which it is added, but it may also be used to modify the pronunciation of a whole word or syllable, or to distinguish between homographs. The value of diacritics is language-dependent.

Ligatures

A ligature is a fusion of two or more ordinary letters into a new glyph. Examples are Æ from AE, Œ from OE, ß (the German eszett) from ſʒ, the Dutch IJ from I and J (Note that ij is capitalised as IJ, never Ij), and the abbreviation & from Latin et "and". The ſs pair is simply an archaic double s. The first glyph is the archaic medial form, and the second the final form.

Digraphs and trigraphs

A digraph is a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters combined. Examples in English are CH, SH, TH. A trigraph is made up of three letters, like SCH in German. In some languages, digraphs and trigraphs can be regarded as part of the alphabet, and independent letters in their own right.

New forms

Eth Ð ð and the Runic letters thorn Þ þ, and wynn Ƿ ƿ were added to the Old English alphabet. Eth and thorn were later replaced with th, and wynn with the new letter w. Although these three letters are no longer part of the English alphabet, eth and thorn are still used in the modern Icelandic alphabet.

Some West, Central and Southern African languages use a few additional letters which have a similar sound value to their equivalents in the IPA. For example, Ga uses the letters Ɛ ɛ, Ŋ ŋ and Ɔ ɔ and Adangme uses Ɛ ɛ and Ɔ ɔ. Hausa uses Ɓ ɓ and Ɗ ɗ for implosives and Ƙ ƙ for an ejective. Africanists have standardized these into the African reference alphabet.

Collation

In some cases, such as with the Swedish symbols Ä, Ö, modified letters are regarded as new individual letters in themselves, and often assigned a specific place in the alphabet for collation purposes, separate from that of the letter on which they are based. In other cases, such as with Ä, Ö, Ü in German, this is not done, letter-diacritic combinations being identified with their base letter. The same applies to digraphs. Different modified letters may be treated differently within a single language. For example, in Spanish the character Ñ is considered a letter in its own, and is sorted between N and O in dictionaries, but the accented vowels Á, É, Í, Ó, Ú are not separated from the unaccented vowels A, E, I, O, U.

Letters of the English alphabet

As used in modern English, the Latin alphabet consists of the following characters

| Majuscule Forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| Minuscule Forms (also called lowercase or small letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

In addition the ligatures, Æ (ash) from AE (e.g. " encyclopædia"), Œ ( oethel) from OE (e.g. " cœlom") can be used for some words derived from Latin and Greek, and diaeresis on the letter ö (e.g. "coöperate") is sometimes used to indicate the pronunciation of "oo". Outside professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures, ligatures and diaeresis are little used in modern English apart from on loan words.

Latin alphabet and international standards

By the 1960s it became apparent to the computer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Standards Organisation (ISO) encapsulated the Latin alphabet in their ( ISO/IEC 646) standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. As the United States held a preeminent position in both industries during the 1960s the standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 x 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 10646 ( Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 x 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin alphabet with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.

| The OSI basic Latin alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Gg | Hh | Ii | Jj | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Vv | Ww | Xx | Yy | Zz | |

| history • palaeography • derivations • diacritics • punctuation • numerals • Unicode • list of letters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||