Sugar

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Food and agriculture

In non-scientific use, the term "sugar" means sucrose (also called "table sugar" or "saccharose") — a white crystalline solid disaccharide. Humans most commonly use sucrose as their sugar of choice for altering the flavor and properties (such as mouthfeel, preservation, and texture) of beverages and food. Commercially-produced table sugar comes either from sugar-cane or from sugar-beet.

In science, sugar refers to any monosaccharide or disaccharide. Monosaccharides (also called "simple sugars"), such as glucose, store energy which biological cells use and consume. In a list of ingredients, any word that ends with "ose" probably denotes a sugar.

In culinary terms, the foodstuff known as sugar delivers one of the primary taste sensations, that of sweetness.

Etymology

The English word "sugar" may ultimately originate from the Sanskrit word sharkara or śarkarā, which means "sugar" or "pebble". It probably came to English by way of the French, Spanish and/or Italians who derived their word for sugar from the Arabic al sukkar (whence the Portuguese word açucar, the Spanish word azúcar, the Italian word zucchero, the Old French word zuchre and the contemporary French word sucre). The Arabs in turn presumably derived their word from the Persian shakar, derived from the original Sanskrit. Compare the OED.

Note that the English word jaggery (coarse brown Indian sugar) has similar ultimate etymological origins.

Production

Table sugar (sucrose) comes from plant sources. Two important sugar crops predominate: sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) and sugar beets (Beta vulgaris), in which sugar can account for 12% to 20% of the plant's dry weight. Some minor commercial sugar crops include the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), sorghum (Sorghum vulgare), and the sugar maple (Acer saccharum). In the financial year 2001/ 2002, worldwide production of sugar amounted to 134.1 million tonnes.

The first production of sugar from sugar-cane took place in India. Alexander the Great's companions reported seeing "honey produced without the intervention of bees" and it remained exotic in Europe until the Arabs started cultivating it in Sicily and Spain. Only after the Crusades did it begin to rival honey as a sweetener in Europe. The Spanish began cultivating sugar-cane in the West Indies in 1506 (and in Cuba in 1523). The Portuguese first cultivated sugar-cane in Brazil in 1532.

Most cane-sugar comes from countries with warm climates, such as Brazil, India, China and Australia. In 2001/2002 developing countries produced over twice as much sugar as developed countries. The greatest quantity of sugar comes from Latin America, the United States, the Caribbean nations, and the Far East.

Beet-sugar comes from regions with cooler climates: northwest and eastern Europe, northern Japan, plus some areas in the United States (including California). In the northern hemisphere, the beet-growing season ends with the start of harvesting around September. Harvesting and processing continues until March in some cases. The availability of processing-plant capacity, and the weather both influence the duration of harvesting and processing - the industry can lay up harvested beet until processed, but frost-damaged beet becomes effectively unprocessable.

The European Union (EU) has become the world's second-largest sugar exporter. The Common Agricultural Policy of the EU sets maximum quotas for members' production to match supply and demand, and a price. Europe exports excess production quota (approximately 5 million tonnes in 2003). Part of this, "quota" sugar, gets subsidised from industry levies, the remainder (approximately half) sells as "C quota" sugar at market prices without subsidy. These subsidies and a high import tariff make it difficult for other countries to export to the EU states, or to compete with the Europeans on world markets.

The U.S. sets high sugar prices to support its producers, with the effect that many former consumers of sugar have switched to corn syrup (beverage-manufacturers) or moved out of the country (candy-makers).

The cheap prices of glucose syrups produced from wheat and corn (maize) threaten the traditional sugar market. In combination with artificial sweeteners, drink manufacturers can produce very low-cost products.

Cane

Cane-sugar producers crush the harvested vegetable material, then collect and filter the juice. They then treat the liquid (often with lime (calcium oxide)) to remove impurities and then neutralize it with sulfur dioxide. Boiling the juice then allows the sediment to settle to the bottom for dredging out, while the scum rises to the surface and for skimming off. In cooling the liquid crystallises, usually in the process of stirring, to produce sugar crystals. Centrifuges usually remove the uncrystallised syrup. The producers can then either sell the resultant sugar, as is, for use; or process it further to produce lighter grades. This processing may take place in another factory in another country.

Beet

Beta vulgaris |

Beet-sugar producers slice the washed beets, then extract the sugar with hot water in a " diffuser". An alkaline solution (" milk of lime" and carbon dioxide from the lime kiln) then serves to precipitate impurities (see carbonatation). After filtration, evaporation concentrates the juice to a content of about 70% solids, and controlled crystallisation extracts the sugar. A centrifuge removes the sugar crystals from the liquid, which gets recycled in the crystalliser stages. When economic constraints prevent the removal of more sugar, the manufacturer discards the remaining liquid, now known as molasses.

Sieving the resultant white sugar produces different grades for selling.

Cane versus beet

Little perceptible difference exists between sugar produced from beet and that from cane. Tests can distinguish the two, and some tests aim to detect fraudulent abuse of EU subsidies or to aid in the detection of adulterated fruit-juice.

The production of sugar results in residues which differ substantially depending on the raw materials used and on the place of production. While cooks often use cane molasses in food, humans find molasses from sugar beet unpalatable, and it therefore ends up mostly as industrial fermentation feedstock, or as animal-feed. Once dried, either type of molasses can serve as fuel for burning.

Culinary sugars

So-called Raw sugars comprise yellow to brown sugars made from clarified cane-juice boiled down to a crystalline solid with minimal chemical processing. Raw sugars result from the processing of sugar-beet juice, but only as intermediates en route to white sugar. Types of raw sugar available as a specialty item outside the tropics include demerara, muscovado, and turbinado. Mauritius and Malawi export significant quantities of such specialty sugars. Manufacturers sometimes prepare raw sugar as loaves rather than as a crystalline powder, by pouring sugar and molasses together into molds and allowing the mixture to dry. This results in sugar-cakes or loaves, called jaggery or gur in India, pingbian tong in China, and panela, panocha, pile, and piloncillo in various parts of Latin America. Truly raw sugar is unheated, made from sugar cane grown on farms in South America, and very difficult to find.

Mill white sugar, also called plantation white, crystal sugar, or superior sugar, consists of raw sugar where the production process does not remove colored impurities, but rather bleaches them white by exposure to sulfur dioxide. This is the most common form of sugar in sugarcane growing areas, but does not store or ship well; after a few weeks, its impurities tend to promote discoloration and clumping.

Blanco directo, a white sugar common in India and other south Asian countries, comes from precipitating many impurities out of the cane juice by using phosphatation — a treatment with phosphoric acid and calcium hydroxide similar to the carbonatation technique used in beet-sugar refining. In terms of sucrose purity, blanco directo is more pure than mill white, but less pure than white refined sugar.

White refined sugar has become the most common form of sugar in North America as well as in Europe. Refined sugar can be made by dissolving raw sugar and purifying it with a phosphoric acid method similar to that used for blanco directo, a carbonatation process involving calcium hydroxide and carbon dioxide, or by various filtration strategies. It is then further decolorized by filtration through a bed of activated carbon or bone char depending on where the processing takes place. Beet sugar refineries produce refined white sugar directly without an intermediate raw stage. White refined sugar is typically sold as granulated sugar, which has been dried to prevent clumping.

Granulated sugar comes in various crystal sizes — for home and industrial use — depending on the application:

- Coarse-grained sugars, such as sanding sugar (nibbed sugar or sugar nibs) find favour for decorating cookies (biscuits) and other desserts.

- Normal granulated sugars for table use: typically they have a grain size about 0.5 mm across

- Finer grades result from selectively sieving the granulated sugar

- caster sugar (0.35 mm), commonly used in baking

- superfine sugar, also called baker's sugar, berry sugar, or bar sugar — favored for sweetening drinks or for preparing meringue

- Finest grades

- Powdered sugar, 10X sugar, confectioner's sugar (0.060 mm), or icing sugar (0.024 mm), produced by grinding sugar to a fine powder. The manufacturer may add a small amount of anti-caking agent to prevent clumping — either cornstarch (1% to 3%) or tri- calcium phosphate.

Retailers also sell sugar cubes or lumps for convenient consumption of a standardised amount.

Brown sugars derive from the late stages of sugar refining, when sugar forms fine crystals with significant molasses-content, or by coating white refined sugar with a cane molasses syrup. Their colour and taste become stronger with increasing molasses-content, as do their moisture-retaining properties. Brown sugars also tend to harden if exposed to the atmosphere, although proper handling can reverse this.

Chemistry

Biochemists regard sugars as relatively simple carbohydrates. Sugars include monosaccharides, disaccharides, trisaccharides and the oligosaccharides - containing 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more monosaccharide units respectively. Sugars contain either aldehyde groups (-CHO) or ketone groups (C=O), where there are carbon-oxygen double bonds, making the sugars reactive. Most sugars conform to (CH2O)n where n is between 3 and 7. A notable exception, deoxyribose, as its name suggests, has a "missing" oxygen atom. As well as being classified by their reactive group, sugars are also classified by the number of carbons they contain. Derivatives of trioses (C3H6O3) are intermediates in glycolysis. Pentoses ( 5 carbon sugars) include ribose and deoxyribose, which are present in nucleic acids. Ribose is also a component of several chemicals that are important to the metabolic process, including NADH and ATP. Hexoses (6 carbon sugars) include glucose which is a universal substrate for the production of energy in the form of ATP. Through photosynthesis plants produce glucose which is then converted for storage as an energy reserve in the form of other carbohydrates such as starch, or as in cane and beet as sucrose.

Many pentoses and hexoses can form ring structures. In these closed-chain forms, the aldehyde or ketone group is not free, so many of the reactions typical of these groups cannot occur. Glucose in solution exists mostly in the ring form at equilibrium, with less than 0.1% of the molecules in the open-chain form.

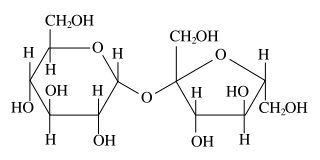

Monosaccharides in a closed-chain form can form glycosidic bonds with other monosaccharides, creating disaccharides (such as sucrose) and polysaccharides (such as starch). Enzymes must hydrolyse or otherwise break these glycosidic bonds before such compounds will metabolise. After digestion and absorption the principal monosaccharides present in the blood and internal tissues are: glucose, fructose, and galactose.

The prefix "glyco-" indicates the presence of a sugar in an otherwise non-carbohydrate substance. Note for example glycoproteins, proteins to which one or more sugars are connected.

Simple sugars include sucrose, fructose, glucose, galactose, maltose, lactose and mannose. Disaccharides occur most commonly as sucrose (cane or beet sugar - made from one glucose and one fructose), lactose (milk sugar - made from one glucose and one galactose) and maltose (made of two glucoses). These disaccharides have the formula C12H22O11.

Hydrolysis can convert sucrose into a syrup of fructose and glucose, producing invert sugar. This resulting syrup is sweeter than the original sucrose, and is useful for making confections because it does not crystalize as easily and thus produces a smoother finished product.

History

The process of making sugar by evaporating juice from sugarcane developed in India around 500 BC. Sugarcane, a tropical grass, probably originated in New Guinea. During prehistoric times its culture spread throughout the Pacific Islands and into India. By 200 BC producers in China had begun to grow it too. Westerners learned of sugarcane in the course of military expeditions into India. Nearchos, one of Alexander the Great's commanders, described it as "a reed that gives honey without bees".

Originally, people chewed the cane raw to extract its sweetness. Sugar refining developed in the India, Middle East and China, where sugar became a staple of cooking and desserts. Early refining methods involved grinding or pounding the cane in order to extract the juice, and then boiling down the juice or drying it in the sun to yield sugary solids that resembled gravel. The Sanskrit word for "sugar" (sharkara), also means "gravel". Similarly, the Chinese use the term "gravel sugar" ( Traditional Chinese: 砂糖) for table sugar.

Sugar later spread to other areas of the world through trade.

The history of cane sugar in the West

The Arabs and Berbers introduced sugar to Western Europe when they conquered the Iberian peninsula in the 8th century AD. Crusaders also brought sugar home with them after their campaigns in the Holy Land, where they encountered caravans carrying "sweet salt".

The 1390s saw the development of a better press, which doubled the juice obtained from the cane. This permitted economic expansion of sugar plantations to Andalucia and to the Algarve. The 1420s saw sugar-production extended to the Canary Islands, Madeira and the Azores.

In August 1492 Christopher Columbus stopped at Gomera in the Canary Islands, for wine and water, intending to stay only four days. He became romantically involved with the Governor of the island, Beatrice de Bobadilla, and stayed a month. When he finally sailed she gave him cuttings of sugarcane, which became the first to reach the New World.

The Portuguese took sugar to Brazil. Hans Staden, published in 1555, writes that by 1540 Santa Catalina Island had 800 sugar-mills and that the north coast of Brazil, Demarara and Surinam had another 2000. Approximately 3000 small mills built before 1550 in the New World created an unprecedented demand for cast iron gears, levers, axles and other implements. Specialist trades in mold making and iron casting were inevitably created in Europe by the expansion of sugar. Sugar mill construction is the missing link of the technological skills needed for the Industrial Revolution that is recognized as beginning in the first part of the 1600s.

After 1625 the Dutch carried sugarcane from South America to the Caribbean islands — from Barbados to the Virgin Islands. The years 1625 to 1750 saw sugar become worth its weight in gold. Prices declined slowly as production became multi-sourced, especially through British colonial policy. Sugar-production increased in mainland North American colonies, in Cuba, and in Brazil. African slaves became the dominant plantation-workers as they proved resistant to the diseases of malaria and yellow fever. European indentured servants remained in shorter supply, susceptible to disease and overall forming a less economic investment. (European diseases such as smallpox had reduced the numbers of local Native Americans.)

With the European colonization of the Americas, the Caribbean became the world's largest source of sugar. These islands could supply sugar-cane using slave-labor and produce sugar at prices vastly lower than those of cane sugar imported from the East. Thus the economies of entire islands such as Guadaloupe and Barbados became based on sugar production. By 1750 the French colony known as Saint-Domingue (subsequently the independent country of Haiti) became the largest sugar-producer in the world. Jamaica too became a major producer in the 18th century. Sugar-plantations fueled a demand for manpower; between 1701 and 1810 ships brought nearly one million slaves to work in Jamaica and in Barbados.

During the eighteenth century, sugar became enormously popular and the sugar-market went through a series of booms. The heightened demand and production of sugar came about to a large extent due to a great change in the eating habits of many Europeans. For example, they began consuming jams, candy, tea, coffee, cocoa, processed foods, and other sweet victuals in much greater numbers. Reacting to this increasing craze, the islands took advantage of the situation and began harvesting sugar in extreme amounts. In fact, they produced up to ninety percent of the sugar that the western Europeans consumed. Of course some islands were more successful than others when it came to producing the product. For instance, Barbados and the British Leewards can be said to have been the most successful in the production of sugar because it counted for 93% and 97% respectively of each island’s exports.

Planters later began developing ways to boost production even more. For example, they began using more animal manure when growing their crops. They also developed more advanced mills and began using better types of sugar-cane. Despite these and other improvements, the prices of sugar reached soaring heights, especially during events such as the revolt against the Dutch and the Napoleonic wars. Sugar remained in high demand, and the islands' planters knew exactly how to take advantage of the situation.

As Europeans established sugar-plantations on the larger Caribbean islands, prices fell, especially in Britain. The previous luxury product began, by the eighteenth century, to be commonly consumed by all levels of society. At first most sugar in Britain was used in tea, but later candies and chocolates became extremely popular. Sugar was commonly sold in solid cones and required a sugar nip, a pliers-like tool, to break off pieces.

Sugar-cane quickly exhausts the soil, and growers pressed larger islands with fresher soil into production in the nineteenth century. In this century, for example, Cuba rose to become the richest land in the Caribbean (with sugar as its dominant crop) because it was the only major island that was free of mountainous terrain. Instead, nearly three-quarters of its land formed a rolling plain which was ideal for planting crops. Cuba also prospered above other islands because they used better methods when harvesting the sugar crops. They had been introduced to modern milling methods such as water mills, enclosed furnaces, steam engines, and vacuum pans. All these technologies increased their productivity.

After the Haïtian Revolution established the independent state of Haiti, sugar production in that country declined and Cuba replaced Saint-Domingue as the world's largest producer.

Long established in Brazil, sugar production spread to other parts of South America, as well as to newer European colonies in Africa and in the Pacific.

The rise of beet sugar

In 1747 the German chemist Andreas Marggraf identified sucrose in beet root. This discovery remained a mere curiosity for some time, but eventually his student Franz Achard built a sugarbeet-processing factory at Cunern in Silesia, under the patronage of Frederick William III of Prussia (reigned 1797 - 1840). While never profitable, this plant operated from 1801 until it suffered destruction during the Napoleonic Wars (ca 1802 - 1815).

Napoleon, cut off from Caribbean imports by a British blockade and at any rate not wanting to fund British merchants, banned sugar imports in 1813. The beet-sugar industry that emerged in consequence grew, and today, sugar-beet provides approximately 30% of world sugar production.

While no longer grown by slaves, sugar from developing countries has an on-going association with workers earning minimal wages and living in extreme poverty. Cuba continued as a large producer of sugar until the late 20th century, when the collapse of the Soviet Union took away its export market and the industry collapsed.

In the developed countries, the sugar industry relies on machinery, with a low requirement for manpower. A large beet-refinery producing around 1,500 tonnes of sugar a day needs a permanent workforce of about 150 for 24-hour production.

Mechanization

Beginning in the late 18th century, sugar production became increasingly mechanized. The steam engine first powered a sugar mill in Jamaica in 1768, and soon thereafter, steam replaced direct firing as the source of process heat.

In 1813 the British chemist Edward Charles Howard invented a method of refining sugar which involved boiling the cane juice not in an open kettle, but in a closed vessel heated by steam and held under partial vacuum. At reduced pressure, water boils at a lower temperature, and this development both saved fuel and reduced the amount of sugar lost through caramelization. Further gains in fuel efficiency came from the multiple-effect evaporator, designed by the African-American engineer Norbert Rillieux perhaps as early as the 1820s, although the first working model dates from 1845. This system consisted of a series of vacuum pans, each held at a lower pressure than the previous one. The vapors from each pan were used to heat the next, and little heat wasted. Today, multiple-effect evaporators are employed widely in many industries for evaporating water.

The process of separating the sugar from the molasses also received mechanical attention: David Weston first applied the centrifuge to this task in Hawaii in 1852.

Sugar as food

Originally a luxury, sugar eventually became sufficiently cheap and common to influence standard cuisine. Britain and the Caribbean islands have cuisines where sugar usage has become particularly prominent.

Sugar forms a prominent element in confectionery and desserts. Cooks use it as a food preservative as well as for sweetening.

Health concerns

Whereas rotting teeth once seemed the most prominent health hazard from the use of sugar, first the growth in the usage of rum (a sugar-cane derivative) and then the predominance of concerns about diabetes and obesity gradually came to prominence.

In 2003, four United Nations agencies, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), commissioned a report compiled by a panel of 30 international experts. The panel stated that the total of free sugars (all monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods by manufacturers, cooks or consumers, plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups and fruit juices) should not account for more than 10% of the energy-intake of a healthy diet, while carbohydrates in total should represent between 55% and 75% of the energy-intake (table 6, page 56 of the WHO Technical Report Series 916, Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases). However, the Sugar Association of the United States of America insists that other evidence indicates that a quarter of human food and drink intake can safely consist of sugar.

Argument continues as to the value of extrinsic sugar (sugar added to food) compared to that of intrinsic sugar (sugars - seldom sucrose - naturally present in food). Adding sugar to food particularly enhances taste, but has the perceived drawback of boosting calories.

In the United States, a scientific/health debate has started over the causes of a steep rise in obesity in the general population — and one view posits increased carbohydrate consumption in recent decades as a major factor.

Sugar economics

In many industrialized countries, sugar has become one of the most heavily-subsidized agricultural products. The European Union, the United States, and Japan all maintain elevated price-floors for sugar through subsidizing domestic production and imposing high tariffs on imports. In recent years, sugar prices in these countries have exceeded prices on the international market by up to three times.

Within international trade bodies, especially in the World Trade Organization, the " G20" countries led by Brazil have argued that because these sugar markets essentially exclude cane-sugar imports, the G20 sugar-producers receive lower prices than they would under free trade. While both the European Union and United States maintain trade agreements whereby certain developing and less-developed countries (LDCs) can sell certain quantities of sugar into their markets, free of the usual import tariffs, countries outside these preferred trade régimes have complained that these arrangements violate the " most favoured nation" principle of international trade.

In 2004, the WTO sided with a group of cane-sugar exporting nations (led by Brazil) and ruled the EU sugar-régime and the accompanying ACP-EU Sugar Protocol (whereby a group of African, Caribbean, and Pacific countries receive preferential access to the European sugar market) illegal. In response, the European Commission proposed on 22 June 2005 a radical reform the EU sugar regime, cutting prices by 39% and eliminating all EU sugar exports. The African, Caribbean, Pacific and Least developed country sugar-exporters have reacted with dismay to the EU sugar proposals, arguing for a fairer reform of the EU regime which would foster development and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals.

Small quantities of sugar, especially speciality grades of sugar, reach the market as ' fair trade' commodities; the fair-trade system produces and sells these products with the understanding that a larger-than-usual fraction of the revenue will support small farmers in the developing world.