Crusades

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Pre 1900 Military; Religious disputes

| Crusades |

|---|

| First – People's – German – 1101 – Second – Third – Fourth – Albigensian – Children's – Fifth – Sixth – Seventh – Shepherds' – Eighth – Ninth – Aragonese – Alexandrian – Nicopolis – Northern – Hussite – Varna |

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns conducted in the name of Christendom and usually sanctioned by the Pope. They were military campaigns of a religious character typically characterized as being waged against pagans, heretics, Muslims or those under the ban of excommunication. When originally conceived, the aim was to recapture Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Muslims while supporting the Byzantine Empire against the " ghazwat" of the Seljuq expansion into Anatolia. The fourth crusade however was diverted and resulted in the conquest of Constantinople. Later crusades were launched against various targets outside of the Levant for a mixture of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the Aragonese Crusade, and the Northern Crusades.

Beyond the medieval military events, the word "crusade" has evolved to have multiple meanings and connotations. For additional meanings, see usage of the term "crusade" below and/or the dictionary definition.

Historical context

- It is necessary to look for the origin of a crusading ideal in the struggle between Christians and Muslims in Spain and consider how the idea of a holy war emerged from this background. — Norman F. Cantor

Western European origins

The origins of the crusades lie in developments in Western Europe earlier in the Middle Ages, as well as the deteriorating situation of the Byzantine Empire in the east, due to a new wave of Turkish Muslim attacks. The breakdown of the Carolingian Empire in the later 9th century, combined with the relative stabilisation of local European borders after the Christianisation of the Vikings, Slavs, and Magyars, had as one side-effect produced a large class of armed warriors whose energies were misplaced fighting one another and terrorizing the local populace. The Church tried to stem this violence with the Peace and Truce of God movements, which was somewhat successful, but trained warriors always sought an outlet for their violence and opportunities for territorial expansion were becoming less attractive for large segments of the nobility. One exception was the Reconquista in Spain and Portugal, which at times occupied Iberian knights and some mercenaries from elsewhere in Europe in the fight against the Islamic Moors, who had attacked and successfully overrun most of the Iberian Peninsula over the preceding two centuries.

In 1009, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah sacked the pilgrimage hospice in Jerusalem and destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. al-Hakim's successors allowed it to be rebuilt later by the Byzantine emperor, but this event was remembered in Europe and may have helped spark the crusades. In 1063, Pope Alexander II had given papal blessing to Iberian Christians in their wars against the Muslims, granting both a papal standard (the vexillum sancti Petri) and an indulgence to those who were killed in battle. Pleas from the Byzantine Emperors, now threatened under by the Seljuks, thus fell on ready ears. These occurred in 1074, from Emperor Michael VII to Pope Gregory VII and in 1095, from Emperor Alexius I Comnenus to Pope Urban II.

The Crusades were, in part, an outlet for an intense religious piety which rose up in the late 11th century among the lay public. A crusader would, after pronouncing a solemn vow, receive a cross from the hands of the pope or his legates, and was thenceforth considered a "soldier of the Church". This was due in part to the Investiture Controversy, which had started around 1075 and was still on-going during the First Crusade. Christendom had emerged as a political conception that supposed the union of all peoples and sovereigns under the direction of the pope and had been greatly affected by the Investiture Controversy; as both sides tried to marshal public opinion in their favour, people became personally engaged in a dramatic religious controversy. The result was an awakening of intense Christian piety and public interest in religious affairs. This was further strengthened by religious propaganda, advocating Just War in order to retake the Holy Land, which included Jerusalem (where the death, resurrection and ascension into heaven of Jesus took place according to Christian theology) and Antioch (the first Christian city), from the Muslims. All of this eventually manifested in the overwhelming popular support for the First Crusade, and the religious vitality of the 12th century.

Middle Eastern situation

This background in the Christian West must be contrasted with that in the Muslim East. Muslim presence in the Holy Land goes back to the initial Arab conquest of Palestine in the 7th century. This did not interfere much with pilgrimage to Christian holy sites or the security of monasteries and Christian communities in the Holy Land of Christendom, and western Europeans were not much concerned with the loss of far-away Jerusalem when, in the ensuing decades and centuries, they were themselves faced with invasions by Muslims and other hostile non-Christians, such as the Vikings and Magyars. However, the Muslim armies' successes were putting strong pressure on the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire.

The turning point in western attitudes towards the east came in the year 1009, when the Fatimid caliph of Cairo, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, had the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem destroyed. His successor permitted the Byzantine Empire to rebuild it under stringent circumstances, and pilgrimage was again permitted, but many reports began to circulate in the West about the cruelty of Muslims toward Christian pilgrims; these accounts from returning pilgrims then played an important role in the development of the crusades later in the century.

After the First Crusade

On a popular level, the first crusades unleashed a wave of impassioned, personally felt pious Christian fury that was expressed in the massacres of Jews that accompanied the movement of the Crusader mobs through Europe, as well as the violent treatment of "schismatic" Orthodox Christians of the east. The violence against the Orthodox Christians culminated in the sack of Constantinople in 1204, in which most of the Crusading armies took part. It should be noted, however that during many of the attacks on Jews, local Bishops and Christians made attempts to protect Jews from the mobs that were passing through. Jews were often offered sanctuary in churches and other Christian buildings, but the mobs broke in and killed them anyway.

The 13th century crusades never expressed such a popular fever, and after Acre fell for the last time in 1291, and after the extermination of the Occitan Cathars in the Albigensian Crusade, the crusading ideal became devalued by Papal justifications of political and territorial aggressions within Catholic Europe.

The last crusading order of knights to hold territory were the Knights Hospitaller. After the final fall of Acre, they took control of the island of Rhodes, and in the sixteenth century, were driven to Malta. These last crusaders were finally unseated by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798.

A list of the crusades

A traditional numbering scheme for the crusades gives us nine during the 11th to 13th centuries, as well as other smaller crusades that are mostly contemporaneous and unnumbered. There were frequent "minor" crusades throughout this period, not only in Palestine, but also in the Iberian Peninsula and central Europe, against not only Muslims, but also Christian heretics and personal enemies of the Papacy or other powerful monarchs. Such "crusades" continued into the 16th century, until the Renaissance and Reformation when the political and religious climate of Europe was significantly different to that of the Middle Ages. The following is a list of crusades.

First Crusade 1095–1099

Full article: First Crusade

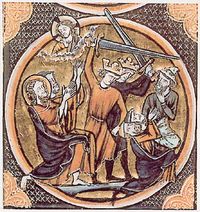

After Byzantine emperor Alexius I called for help with defending his empire against the Seljuk Turks, in 1095 at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to join a war against the Turks, a war which would count as full penance. Crusader armies managed to defeat two substantial Turkish forces at Dorylaeum and at Antioch, finally marching to Jerusalem with only a fraction of their original forces. In 1099, they took Jerusalem by assault and massacred the population. As a result of the First Crusade, several small Crusader states were created, notably the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Crusade of 1101

Full article: Crusade of 1101

Following this crusade there was a second, less successful wave of crusaders. This is known as the crusade of 1101 and may be considered an adjunct of the first crusade.

Second Crusade 1145–1149

Full article: Second Crusade

After a period of relative peace, in which Christians and Muslims co-existed in the Holy Land, Muslims conquered the town of Edessa. A new crusade was called for by various preachers, most notably by Bernard of Clairvaux. French and German armies, under the Kings Louis VII and Conrad III respectively, marched to Jerusalem in 1147, but failed to accomplish any major successes, and indeed endangered the survival of the Crusader states with a strategically foolish attack on Damascus. By 1150, both leaders had returned to their countries without any result.

Third Crusade 1189–1192

Full article: Third Crusade

Also known as the Kings' Crusade. In 1187, Saladin, Sultan of Egypt, recaptured Jerusalem. Pope Gregory VIII called for a crusade, which was led by several of Europe's most important leaders: Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor. Frederick drowned in Cilicia in 1190, leaving an unstable alliance between the English and the French. Philip left, in 1191, after the Crusaders had recaptured Acre from the Muslims. The Crusader army headed down the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. They defeated the Muslims near Arsuf and were in sight of Jerusalem. However, the inability of the Crusaders to thrive in the locale due to inadequate food and water resulted in an empty victory. Richard left the following year after establishing a truce with Saladin. On Richard's way home, his ship was wrecked and he ended up in Austria, where his enemy, Duke Leopold, captured him. The Duke delivered Richard to Emperor Henry VI, who held the King for ransom. By 1197, Henry felt himself ready for a Crusade, but he died in the same year of malaria. Richard I died during fighting in Europe and never returned to the Holy Land.

Fourth Crusade 1201–1204

Full article: Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade was initiated in 1202 by Pope Innocent III, with the intention of invading the Holy Land through Egypt. The Venetians, under Doge Enrico Dandolo, gained control of this crusade and diverted it first to the Christian city of Zara ( Zadar), then to Constantinople, where they attempted to place a Byzantine exile on the throne. After a series of misunderstandings and outbreaks of violence, the Crusaders sacked the city in 1204.

Albigensian Crusade

Full article: Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade was launched in 1209 to eliminate the heretical Cathars of southern France. It was a decades-long struggle that had as much to do with the concerns of northern France to extend its control southwards as it did with heresy. In the end, both the Cathars and the independence of southern France were exterminated.

Children's Crusade

Full article: Children's Crusade

The Children's Crusade is a series of possibly fictitious or misinterpreted events of 1212. The story is that an outburst of the old popular enthusiasm led a gathering of children in France and Germany, which Pope Innocent III interpreted as a reproof from heaven to their unworthy elders. The leader of the French army, Stephen, led 30,000 children. The leader of the German army, Nicholas, led 7,000 children. None of the children actually reached the Holy Land; they were either sold as slaves, settled along the route to Jerusalem, or died of hunger during the journey.

Fifth Crusade 1217–1221

Full article: Fifth Crusade

By processions, prayers, and preaching, the Church attempted to set another crusade on foot, and the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) formulated a plan for the recovery of the Holy Land. In the first phase, a crusading force from Hungary, Austria joined the forces of the king of Jerusalem and the prince of Antioch to take back Jerusalem. In the second phase, crusader forces achieved a remarkable feat in the capture of Damietta in Egypt in 1219, but under the urgent insistence of the papal legate, Pelagius, they proceeded to a foolhardy attack on Cairo, and an inundation of the Nile compelled them to choose between surrender and destruction.

Sixth Crusade 1228–1229

Full article: Sixth Crusade

Emperor Frederick II had repeatedly vowed a crusade, but failed to live up to his words, for which he was excommunicated by the Pope in 1228. He nonetheless set sail from Brindisi, landed in Palestine and through diplomacy he achieved unexpected success, Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem being delivered to the Crusaders for a period of ten years.

Seventh Crusade 1248–1254

Full article: Seventh Crusade

The papal interests represented by the Templars brought on a conflict with Egypt in 1243, and in the following year a Khwarezmian force summoned by the latter stormed Jerusalem. The Crusaders were drawn into battle at La Forbie in Gaza. The Crusader army and its Bedouin mercenaries were outnumbered by Baibars' force of Khwarezmian tribesmen and were completely defeated within forty-eight hours. This battle is considered by many historians to have been the death knell to the Kingdom of Outremer. Although this provoked no widespread outrage in Europe as the fall of Jerusalem in 1187 had done, Louis IX of France organized a crusade against Egypt from 1248 to 1254, leaving from the newly constructed port of Aigues-Mortes in southern France. It was a failure and Louis spent much of the crusade living at the court of the Crusader kingdom in Acre. In the midst of this crusade was the first Shepherds' Crusade in 1251.

Eighth Crusade 1270

Full article: Eighth Crusade

The eighth Crusade was organized by Louis IX in 1270, again sailing from Aigues-Mortes, initially to come to the aid of the remnants of the Crusader states in Syria. However, the crusade was diverted to Tunis, where Louis spent only two months before dying. The Eighth Crusade is sometimes counted as the Seventh, if the Fifth and Sixth Crusades are counted as a single crusade. The Ninth Crusade is sometimes also counted as part of the Eighth.

Ninth Crusade 1271–1272

Full article: Ninth Crusade

The future Edward I of England undertook another expedition in 1271, after having accompanied Louis on the Eighth Crusade. He accomplished very little in Syria and retired the following year after a truce. With the fall of Antioch (1268), Tripoli (1289), and Acre (1291), the last traces of the Christian rule in Syria disappeared.

Northern Crusades (Baltic and Germany)

Full article: Northern Crusades

The Crusades in the Baltic Sea area and in Central Europe were efforts by (mostly German) Christians to subjugate and convert the peoples of these areas to Christianity. These Crusades ranged from the 12th century, contemporaneous with the Second Crusade, to the 16th century.

Between 1232 and 1234, there was a crusade against the Stedingers. This crusade was special, because the Stedingers were not heathens or heretics, but fellow Roman Catholics. They were free Frisian farmers who resented attempts of the count of Oldenburg and the archbishop Bremen-Hamburg to make an end to their freedoms. The archbishop excommunicated them and the pope declared a crusade in 1232. The Stedingers were defeated in 1234.

Other crusades

Crusade against the Tatars

In the 14th century, Khan Tokhtamysh combined the Blue and White Hordes forming the Golden Horde. It seemed that the power of the Golden Horde had begun to rise, but in 1389, Tokhtamysh made the disastrous decision of waging war on his former master, the great Tamerlane. Tamerlane's hordes rampaged through southern Russia, crippling the Golden Horde's economy and practically wiping out its defenses in those lands.

After losing the war, Tokhtamysh was then dethroned by the party of Khan Temur Kutlugh and Emir Edigu, supported by Tamerlane. When Tokhtamysh asked Vytautas the Great for assistance in retaking the Horde, the latter readily gathered a huge army which included Lithuanians, Ruthenians, Russians, Mongols, Moldavians, Poles, Romanians and Teutonic knights.

In 1398, the huge army moved from Moldavia and conquered the southern steppe all the way to the Dnieper River and northern Crimea. Inspired by their great successes, Vytautas declared a 'Crusade against the Tatars' with Papal backing. Thus, in 1399, the army of Vytautas once again moved on the Horde. His army met the Horde's at the Vorskla River, slightly inside Lithuanian territory.

Although the Lithuanian army was well equipped with cannons, it could not resist a rear attack from Edigu's reserve units. Vytautas hardly escaped alive. Many princes of his kin—possibly as many as 20—were killed (as for example, Stefan Musat, Prince of Moldavia and two of his brothers, while a fourth was badly injured ), and the victorious Tatars besieged Kiev. "And the Christian blood flowed like water, up to the Kievan walls," as one chronicler put it. Meanwhile, Temur Kutlugh died from the wounds received in the battle, and Tokhtamysh was killed by one of his own men.

Crusades in the Balkans

To counter the expanding Ottoman Empire, several crusades were launched in the XV. century. The most notable are:

- the Crusade of Nicopolis (1396) organized by Sigismund of Luxemburg king of Hungary culminated in the Battle of Nicopolis. It is often called the last of the crusades.

- the Crusade of Varna (1444) led by the Polish-Hungarian king Władysław Warneńczyk ended in the Battle of Varna

- and the Crusade of 1456 organized to lift the Siege of Belgrade led by John Hunyadi and Giovanni da Capistrano

The Aragonese Crusade

The Aragonese Crusade or Crusade of Aragón was declared by Pope Martin IV against the King of Aragón, Peter III the Great, in 1284 and 1285.

The Alexandrian Crusade

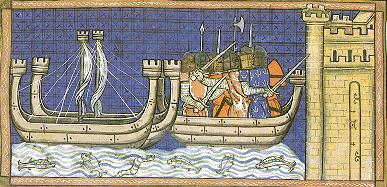

The Alexandrian Crusade of October 1365 was a minor seaborne Crusade against Muslim Alexandria led by Peter I of Cyprus. His motivation was at least as commercial as religious. It had limited success.

The Hussite Crusade

The Hussite Crusade(s), also known as the " Hussite Wars," or the "Bohemian Wars," involved the military actions against and amongst the followers of Jan Hus in Bohemia in the period 1420 to circa 1434. The Hussite Wars were arguably the first European war in which hand-held gunpowder weapons such as muskets made a decisive contribution. The Hussite warriors were basically infantry, and their many defeats of larger armies with heavily armoured knights helped effect the infantry revolution. In the end, it was an inconclusive war.

The Swedish Crusades

The Swedish conquest of Finland in the Middle Ages has traditionally been divided into three "crusades": the First Swedish Crusade around 1155 CE, the Second Swedish Crusade about 1249 CE and the Third Swedish Crusade in 1293 CE.

The first crusade is purely legendary, and according to most historians today, never took place as described in the legend and did not result in any ties between Finland and Sweden. For the most part, it was made up in the late 13th century to date the Swedish rule in Finland further back in time. No historical record has also survived describing the second one, but it probably was done and ended up in the concrete conquest of southwestern Finland. The third one was against Novgorod, and is properly documented by both parties of the conflict.

According to archaeological finds, Finland was largely Christian already before the said crusades. Thus the "crusades" can rather be seen as ordinary expeditions of conquest whose main target was territorial gain. The expeditions were dubbed as actual crusades only in the 19th century by the national-romanticist Swedish and Finnish historians.

Historical perspectives on the Crusades

Western versus Eastern interpretation

Western and Eastern historiography present variously different views on the Crusades, in large part because "crusade" invokes dramatically opposed sets of associations - "crusade" as a valiant struggle for a supreme cause, and "crusade" as a byword for barbarism and aggression. This contrasting view is not recent, as Christians have in the past struggled with the tension of military activity and teachings of Christ to "love ones enemies" and to "turn the other cheek". For these reasons, the crusades have been controversial even among contemporaries.

Western sources speak of both heroism, faith and honour (emphasized in chivalric romance), but also of acts of brutality. Islamic and Orthodox Christian chroniclers tell stories of barbarian savagery and brutality.

Likewise, some modern historians in the west express moral outrage - for example Steven Runciman, the leading western historian of the Crusades for much of the 20th century, ended his history with a resounding condemnation:

- "High ideals were besmirched by cruelty and greed.. the Holy War was nothing more than a long act of intolerance in the name of God".

1908 Catholic Encyclopedia perspective

One traditional Catholic perspective is presented in the 1908 version of the Catholic Encyclopedia. This viewpoint sees the Crusades as defensive wars against Muslim aggression and "Mohammedan tyranny" . The 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia summarizes its traditional Roman Catholic viewpoints on the legacy of the Crusades:

| Notwithstanding their final overthrow, the Crusades hold a very important place in the history of the world... It must be said that the advantages thus acquired by the popes were for the common safety of Christendom. From the outset the Crusades were defensive wars and checked the advance of the Mohammedans who, for two centuries, concentrated their forces in a struggle against the Christian settlements in Syria; hence Europe is largely indebted to the Crusades for the maintenance of its independence." [Catholic Encyclopedia ] |

It should be noted that this viewpoint is not the only viewpoint on the Crusades to be found in the Roman Catholic tradition.

Eastern Orthodoxy

Like Muslims, Eastern Orthodox Christians also see the Crusades as attacks by "the barbarian West", but centered on the sack of Constantinople in 1204. Many relics and artifacts taken from Constantinople are still in the West, in the Vatican and elsewhere. Disagreement currently exists between modern Turks and Greeks over the claimant rights to the Greek Horses on the facade of St. Mark's in Venice. The Greeks argue that the frieze is inherently part of Greek culture and identity, similar to the "Elgin" Marbles and the Turks counter that the freize originated from what is now modern-day Istanbul. A picture of Turkish popular history of the Crusades can be assembled by compiling text of official Turkish brochures on Crusader fortifications in the Aegean coast and coastal islands.

Countries of Central Europe, despite the fact that they also belonged to Western Christianity, were the most skeptical about the idea of Crusades. Many cities in Hungary were sacked by passing bands of Crusaders; Polish Prince Leszek I the White refused to join a Crusade, allegedly because of the lack of mead in Palestine. Later on, Poles were themselves subject to conquest from the Crusaders (see Teutonic Order), and therefore championed the notion that pagans have the right to live in peace and have property rights to their lands (see Pawel Wlodkowic).

Popular reputation in Western Europe

In Western Europe, the Crusades have traditionally been regarded by laypeople as heroic adventures, though the mass enthusiasm of common people was largely expended in the First Crusade, from which so few of their class returned. Today, the " Saracen" adversary is crystallized in the lone figure of Saladin; his adversary Richard the Lionheart is, in the English-speaking world, the archetypical crusader king, while Frederick Barbarossa (illustration, below left) and Louis IX fill the same symbolic niche in German and French culture. Even in contemporary areas, the crusades and their leaders were romanticized in popular literature; the Chanson d'Antioche was a chanson de geste dealing with the First Crusade, and the Song of Roland, dealing with the era of the similarly romanticized Charlemagne, was directly influenced by the experience of the crusades, going so far as to replace Charlemagne's historic Basque opponents with Muslims. A popular theme for troubadours was the knight winning the love of his lady by going on crusade in the east.

In the 14th century, Godfrey of Bouillon was united with the Trojan War and the adventures of Alexander the Great against a backdrop for military and courtly heroics of the Nine Worthies who stood as popular secular culture heroes into the 16th century, when more critical literary tastes ran instead to Torquato Tasso and Rinaldo and Armida, Roger and Angelica. Later, the rise of a more authentic sense of history among literate people brought the Crusades into a new focus for the Romantic generation in the romances of Sir Walter Scott in the early 19th century. Crusading imagery could be found even in the Crimean War, in which the United Kingdom and France were allied with the Muslim Ottoman Empire, and in World War I, especially Allenby's capture of Jerusalem in 1917 (illustration, below right).

In Spain, the popular reputation of the Crusades is outshone by the particularly Spanish history of the Reconquista. El Cid is the central figure.

Legacy of the Crusades

The Crusades had profound and lasting historical impacts.

Europe

The Crusades have been remembered relatively favourably in western Europe (countries which were, at the time of the Crusades, Roman Catholic countries). (Nonetheless, there have certainly been many vocal critics of the Crusades in Western Europe since the renaissance.)

Politics and culture

The Crusades had an enormous influence on the European Middle Ages. At times, much of the continent was united under a powerful Papacy, but by the 14th century, the development of centralized bureaucracies (the foundation of the modern nation-state) was well on its way in France, England, Burgundy, Portugal, Castile, and Aragon partly because of the dominance of the church at the beginning of the crusading era.

Although Europe had been exposed to Islamic culture for centuries through contacts in Iberian Peninsula and Sicily, much knowledge in areas such as science, medicine, and architecture, was transferred from the Islamic to the western world during the crusade era.

The military experiences of the crusades also had their effects in Europe; for example, European castles became massive stone structures, as they were in the east, rather than smaller wooden buildings as they had typically been in the past.

In addition, the Crusades are seen as having opened up European culture to the world, especially Asia:

| The Crusades brought about results of which the popes had never dreamed, and which were perhaps the most, important of all. They re-established traffic between the East and West, which, after having been suspended for several centuries, was then resumed with even greater energy; they were the means of bringing from the depths of their respective provinces and introducing into the most civilized Asiatic countries Western knights, to whom a new world was thus revealed, and who returned to their native land filled with novel ideas... If, indeed, the Christian civilization of Europe has become universal culture, in the highest sense, the glory redounds, in no small measure, to the Crusades." [Catholic Encyclopedia ] |

Along with trade, new scientific discoveries and inventions made their way east or west. Arabic advances (including the development of Algebra, optics, and refinement of engineering) made their way west and sped the course of advancement in European universities that led to the Renaissance in later centuries.

The invasions of German crusaders prevented formation of the large Lithuanian state incorporating all Baltic nations and tribes. Lithuania was destined to become small country and forced to expand to the East looking for resources for wars with crusaders.

Trade

The need to raise, transport and supply large armies led to a flourishing of trade throughout Europe. Roads largely unused since the days of Rome saw significant increases in traffic as local merchants began to expand their horizons. This was not only because the Crusades prepared Europe for travel, but rather that many wanted to travel after being reacquainted with the products of the Middle East. This also aided in the beginning of the Renaissance in Italy, as various Italian city-states from the very beginning had important and profitable trading colonies in the crusader states, both in the Holy Land and later in captured Byzantine territory.

Increased trade brought many things to Europeans that were once unknown or extremely rare and costly. These goods included a variety of spices, ivory, jade, diamonds, improved glass-manufacturing techniques, early forms of gun powder, oranges, apples, and other Asian crops, and many other products.

Wider geo-political effects

Despite the ultimate defeat in the Middle East, the Crusaders were successful in regaining the Iberian Peninsula permanently and slowed down the military expansion of Islam.

The successful international coordination of Crusading forces from different countries, and the reduction (not cessation) in fighting between Christian monarchs that the crusading ideal encouraged, allowed Christian Europe to remain strong in the face of Muslim military expansionism. It is therefore likely that a considerable part of modern Christian Europe (particularly Spain, Portugal, and the Balkans) would be Muslim today had the Crusades not occurred, and it is furthermore possible that Christianity might have been largely replaced by Islam throughout Europe. (This is one traditional Roman Catholic perspective: See below.)

The achievement of preserving Christian Europe must not, however, ignore the eventual fall of the Christian Byzantine Empire, which was in large part due to the Fourth Crusade's extreme aggression against Eastern Orthodox Christianity, largely at the instigation of the infamous Enrico Dandolo, the Doge of Venice and financial backer of the Fourth Crusade. The Byzantine lands had been a stable Christian state since the fourth century. After the Crusaders took Constantinople in 1204, the Byzantines never again had as large or strong a state and finally fell in 1453.

Taking into account the fall of the Byzantines, the Crusades could be portrayed as the defence of Roman Catholicism against the violent expansion of Islam, rather than the defence of Christianity as a whole against Islamic expansion. On the other hand, the Fourth Crusade could be presented as an anomaly. It is also possible to find a compromise between these two points of view, specifically that the Crusades were Roman Catholic campaigns which primarily sought to fight Islam to preserve Catholicism, and secondarily sought to thereby protect the rest of Christianity; in this context, the Fourth Crusade's crusaders could have felt compelled to abandon the secondary aim in order to retain Dandolo's absolutely essential logistical support in achieving the primary aim. Even so, the Fourth Crusade was condemned by the Pope of the time, and is now generally remembered throughout Europe as a disgraceful failure.

Islamic world

The crusades had profound but localized effects upon the Islamic world, where the equivalents of "Franks" and "Crusaders" remained expressions of disdain. Muslims traditionally celebrate Saladin, the Kurdish warrior, as a hero against the Crusaders. In the 21st century, some in the Arab world, such as the Arab independence movement and Pan-Islamism movement, continue to call Western involvement in the Middle East a "crusade". The Crusades were regarded by the Islamic world as cruel and savage onslaughts by European Christians.

Jewish community

The Crusaders' atrocities against Jews in the German and Hungarian towns, later also in those of France and England, and in the massacres of Jews in Palestine and Syria have become a significant part of the history of anti-Semitism, although no Crusade was ever declared against Jews. These attacks left behind for centuries strong feelings of ill will on both sides. The social position of the Jews in western Europe was distinctly worsened, and legal restrictions increased during and after the Crusades. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III and formed the turning-point in medieval anti-Semitism.

The Crusading period brought with it many narratives from Jewish sources. Among the better-known Jewish narratives are the chronicles of Solomon Bar Simson and Rabbi Eliezer bar Nathan, The Narrative of the Old Persecutions by Mainz Anonymous, and Sefer Zekhirah, and The Book of Remembrance, by Rabbi Ephraim of Bonn.

The Caucasus

In the Caucasus mountains of Georgia, in the remote highland region of Khevsureti, a tribe called the Khevsurs are thought to possibly be direct descendants of a party of crusaders, who got separated from a larger army and have remained in isolation with some of the crusader culture intact. Into the 20th century, relics of armor, weaponry and chain mail were still being used and passed down in such communities. Russian serviceman and ethnographer Arnold Zisserman who spent 25 years (1842–67) in the Caucasus, believed the exotic group of Georgian highlanders were descendants of the last Crusaders based on their customs, language, art and other evidence. American traveler Richard Halliburton (1900–1939) saw and recorded the customs of the tribe in 1935.

Etymology and use of the term "crusade"

The crusades were never referred to as such by their participants. The original crusaders were known by various terms, including fideles Sancti Petri (the faithful of St. Peter) or milites Christi (knights of Christ). They saw themselves as undertaking an iter, a journey, or a peregrinatio, a pilgrimage, though pilgrims were usually forbidden from carrying arms. Like pilgrims, each crusader swore a vow (a votus), to be fulfilled on successfully reaching Jerusalem, and they were granted a cloth cross (crux) to be sewn into their clothes. This "taking of the cross", the crux, eventually became associated with the entire journey; the word "crusade" (coming into English from the French croisade, the Italian crociata, or the Portuguese cruzada) developed from this.

Since the 17th century, the term "crusade" has carried a connotation in the West of being a righteous campaign, usually to "root out evil", or to fight for a just cause. In a non-historical common or theological use, "crusade" has come to have a much broader emphatic or religious meaning —substantially removed from "armed struggle."

In a broader sense, "crusade" can be used, always in a rhetorical and metaphorical sense, to identify as righteous any war that is given a religious justification.

Ardent activists may also refer to their causes as "crusades," as in the "Crusade against Adult Illiteracy," or a "Crusade against Littering." In recent years, however, the use of "crusade" as a positive term has become less frequent in order to avoid giving offense to Muslims or others offended by the term. The term may also sarcastically or pejoratively characterize the zealotry of agenda promoters, for example with the monicker "Public Crusader" or the campaigns "Crusade against abortion," and the "Crusade for prayer in public schools."