Vanadium

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Chemical elements

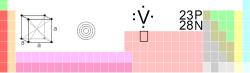

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, Symbol, Number | vanadium, V, 23 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical series | transition metals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, Period, Block | 5, 4, d | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silver-grey metal |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic mass | 50.9415 (1) g/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d3 4s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 11, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 6.0 g·cm−3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Liquid density at m.p. | 5.5 g·cm−3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2183 K (1910 ° C, 3470 ° F) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3680 K (3407 ° C, 6165 ° F) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 21.5 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 459 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat capacity | (25 °C) 24.89 J·mol−1·K−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | cubic body centered | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 2, 3, 4, 5 ( amphoteric oxide) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 1.63 (Pauling scale) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies ( more) |

1st: 650.9 kJ·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 1414 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 2830 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | 135 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius (calc.) | 171 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 125 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ??? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | (20 °C) 197 nΩ·m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | (300 K) 30.7 W·m−1·K−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | (25 °C) 8.4 µm·m−1·K−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound (thin rod) | (20 °C) 4560 m/s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 128 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 47 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 160 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.37 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 7.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 628 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 628 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7440-62-2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Selected isotopes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| References | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vanadium ( IPA: /vəˈneɪdiəm/) is a chemical element in the periodic table that has the symbol V and atomic number 23. A rare, soft and ductile element, vanadium is found combined in certain minerals and is used mainly to produce certain alloys. It is one of the 26 elements commonly found in living things.

Notable characteristics

Vanadium is a soft and ductile, silver-grey metal. It has good resistance to corrosion by alkalis, sulfuric and hydrochloric acid. It oxidizes readily at about 933 K. Vanadium has good structural strength and a low fission neutron cross section, making it useful in nuclear applications. Although a metal, it shares with chromium and manganese the property of having valency oxides with acid properties.

Common oxidation states of vanadium include +2, +3, +4 and +5. A popular experiment with ammonium vanadate NH4VO3, reducing the compound with zinc metal, can demonstrate colorimetrically all four of these vanadium oxidation states. A +1 oxidation state is rarely seen.

Applications

Approximately 80% of vanadium produced is used as ferrovanadium or as a steel additive. Other uses:

- In such alloys as:

- specialty stainless steel, e.g. for use in surgical instruments and tools.

- rust resistant and high speed tool steels.

- mixed with aluminium in titanium alloys used in jet engines and high-speed airframes

- Vanadium steel alloys are used in axles, crankshafts, gears, and other critical components.

- It is an important carbide stabilizer in making steels.

- Because of its low fission neutron cross section, vanadium has nuclear applications.

- Vanadium foil is used in cladding titanium to steel.

- Vanadium-gallium tape is used in superconducting magnets (175,000 gauss).

- Vanadium pentoxide V2O5 is used as a catalyst in manufacturing sulfuric acid (via the contact process) and maleic anhydride. It is also used in making ceramics.

- Glass coated with vanadium dioxide VO2 can block infrared radiation (and not visible light) at a specific temperature.

- Electrical fuel cells and storage batteries such as vanadium redox batteries.

- Added to corundum to make simulated Alexandrite jewelry.

- Vanadate electrochemical conversion coatings for protecting steel against rust and corrosion

History

Vanadium was originally discovered by Andrés Manuel del Río (a Spanish mineralogist) in Mexico City, in 1801. He called it "brown lead" (now named vanadinite). Through experimentation, its colors reminded him of chromium, so he named the element panchromium. He later renamed this compound erythronium, since most of the salts turned red when heated. The French chemist Hippolyte Victor Collet-Descotils incorrectly declared that del Rio's new element was only impure chromium. Del Rio thought himself to be mistaken and accepted the statement of the French chemist that was also backed by Del Rio's friend Baron Alexander von Humboldt.

In 1831, Sefström of Sweden rediscovered vanadium in a new oxide he found while working with some iron ores and later that same year Friedrich Wöhler confirmed del Rio's earlier work. Later, George William Featherstonhaugh, one of the first US geologists, suggested that the element should be named "rionium" after Del Rio, but this never happened.

Metallic vanadium was isolated by Henry Enfield Roscoe in 1867, who reduced vanadium(III) chloride VCl3 with hydrogen. The name vanadium comes from Vanadis, a goddess in Scandinavian mythology, because the element has beautiful multicolored chemical compounds.

Biological role

In biology, a vanadium atom is an essential component of some enzymes, particularly the vanadium nitrogenase used by some nitrogen-fixing micro-organisms. Vanadium is essential to ascidians or sea squirts in vanadium chromagen proteins. The concentration of vanadium in their blood is more than 100 times higher than the concentration of vanadium in the seawater around them. Rats and chickens are also known to require vanadium in very small amounts and deficiencies result in reduced growth and impaired reproduction.

Administration of oxovanadium compounds has been shown to alleviate diabetes mellitus symptoms in certain animal models and humans. Much like the chromium effect on sugar metabolism, the mechanism of this effect is unknown.

Mineral supplement in drinking water

Vanadium pentoxide V2O5 is marketed in Japan as a good mineral health supplement naturally occurring in drinking water. The source of this drinking water is mainly the slopes of Mount Fuji. The water's vanadium pentoxide content ranges from about 80 to 130 μg/liter. It is marketed as being effective against diabetes, eczema, and obesity. There is no mention of its toxicity in the marketing of these products.

Occurrence

Vanadium is never found unbound in nature but it does occur in about 65 different minerals among which are patronite VS4, vanadinite Pb5(VO4)3Cl, and carnotite K2(UO2)2(VO4)2.3H2O. Vanadium is also present in bauxite, and in carbon containing deposits such as crude oil, coal, oil shale and tar sands. Vanadium has also been detected spectroscopically in light from the Sun and some other stars.

Much of the vanadium metal being produced is now made by calcium reduction of V2O5 in a pressure vessel. Vanadium is usually recovered as a by-product or co-product, and so world resources of the element are not really indicative of available supply.

Isolation

Vanadium is available commercially and production of a sample in the laboratory is not normally required. Commercially, routes leading to metallic vanadium as main product are not usually required as enough is produced as byproduct in other processes.

In industry, heating of vanadium ore or residues from other processes with salt NaCl or sodium carbonate Na2CO3 at about 850°C gives sodium vanadate NaVO3. This is dissolved in water and acidified to give a red solid which in turn is melted to form a crude form of vanadium pentoxide V2O5. Reduction of vanadium pentoxide with calcium gives pure vanadium. An alternative suitable for small scales is the reduction of vanadium pentachloride VCl5 with hydrogen or magnesium. Many other methods are also in use.

Industrially, most vanadium is used as an additive to improve steels. Rather than proceed via pure vanadium metal it is often sufficient to react the crude of vanadium pentoxide V2O5 with crude iron. This produces ferrovanadium suitable for further work.

Compounds

Vanadium pentoxide V2O5 is used as a catalyst principally in the production of sulfuric acid. It is the source of vanadium used in the manufacture of ferrovanadium. It can be used as a dye and colour-fixer.

Vanadyl sulfate VOSO4, also called vanadium(IV) sulfate oxide hydrate, is used as a relatively controversial dietary supplement, primarily for increasing insulin levels and body-building. Whether it works for the latter purpose has not been proven, and there is some evidence that athletes who take it are merely experiencing a placebo effect.

Vanadium(IV) chloride VCl4 is a soluble form of vanadium that is commonly used in the laboratory. V(IV) is the reduced form of V(V), and commonly occurs after anaerobic respiration by dissimilatory metal reducing bacteria. VCl4 reacts violently with water.

Toxicity of vanadium compounds

The toxicity of vanadium depends on its physico-chemical state; particularly on its valence state and solubility. Pentavalent VOSO4 has been reported to be more than 5 times as toxic as trivalent V2O3 (Roschin, 1967). Vanadium compounds are poorly absorbed through the gastrointestinal system. Inhalation exposures to vanadium and vanadium compounds result primarily in adverse effects to the respiratory system (Sax, 1984; ATSDR, 1990). Quantitative data are, however, insufficient to derive a subchronic or chronic inhalation.

There is little evidence that vanadium or vanadium compounds are reproductive toxins or teratogens. There is also no evidence that any vanadium compound is carcinogenic; however, very few adequate studies are available for evaluation. Vanadium has not been classified as to carcinogenicity by the U.S. EPA (1991a).

Isotopes

Naturally occurring vanadium is composed of one stable isotope 51V and one radioactive isotope 50V with a half-life of 1.5×1017 years. 24 artificial radioisotopes have been characterized (in the range of mass number between 40 and 65) with the most stable being 49V with a half-life of 330 days, and 48V with a half-life of 15.9735 days. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives shorter than an hour, the majority of them below 10 seconds. In 4 isotopes, metastable excited states were found (including 2 metastable states for 60V).

The primary decay mode before the most abundant stable isotope 51V is electron capture. The next most common mode is beta decay. The primary decay products before 51V are element 22 (titanium) isotopes and the primary products after are element 24 (chromium) isotopes.

Precautions

Powdered metallic vanadium is a fire hazard, and unless known otherwise, all vanadium compounds should be considered highly toxic. Generally, the higher the oxidation state of vanadium, the more toxic the compound is. The most dangerous one is vanadium pentoxide.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set an exposure limit of 0.05 mg/m3 for vanadium pentoxide dust and 0.1 mg/m3 for vanadium pentoxide fumes in workplace air for an 8-hour workday, 40-hour work week.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has recommended that 35 mg/m3 of vanadium be considered immediately dangerous to life and health. This is the exposure level of a chemical that is likely to cause permanent health problems or death.