Absinthe

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Drink

Absinthe (also absinth) ( IPA English: [ˈæbsɪnθ] IPA French: [ap.sɛ̃t]) is a distilled, highly alcoholic, anise- flavored spirit derived from herbs including the flowers and leaves of the medicinal plant Artemisia absinthium, also called wormwood. Although it is sometimes incorrectly called a liqueur, absinthe is not bottled with added sugar and is therefore classified as a liquor or spirit.

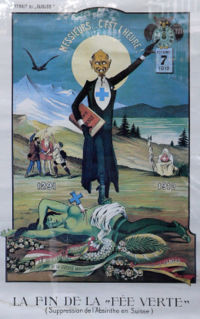

Absinthe is often referred to as la Fée Verte ('The Green Fairy') because of its coloring — typically pale or emerald green, but sometimes clear or in rare cases rose red. Due to its high proof and concentration of oils, absintheurs (absinthe drinkers) typically add three to five parts ice-cold water to a dose of absinthe, which causes the drink to turn cloudy (called 'louching'); often the water is used to dissolve added sugar to decrease bitterness. This preparation is considered an important part of the experience of drinking absinthe, so much so that it has become ritualized, complete with special slotted absinthe spoons and other accoutrements. Absinthe's flavor is similar to anise-flavored liqueurs, with a light bitterness and greater complexity imparted by multiple herbs.

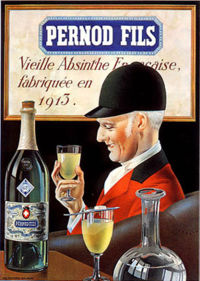

Modern absinthe originated in Switzerland as an elixir but is better known for its popularity in late 19th and early 20th century France, particularly among Parisian artists and writers whose romantic associations with the drink still linger in popular culture. In its heyday, the most popular brand of absinthe worldwide was Pernod Fils. At the height of this popularity, absinthe was portrayed as a dangerously addictive, psychoactive drug; the chemical thujone was blamed for most of its deleterious effects. By 1915, it was banned in a number of European countries and the United States. Even though it was vilified, no evidence shows it to be any more dangerous than ordinary alcohol. A modern absinthe revival began in the 1990s, as countries in the European Union began to reauthorize its manufacture and sale.

Etymology

The French word absinthe can refer either to the liquor or to the actual wormwood plant (grande absinthe being Artemisia absinthium, and petite absinthe being Artemisia pontica). The word derives from the Latin absinthium, which is in turn a stylization of the Greek αψινθιον (apsinthion). Some claim that the word means 'undrinkable' in Greek, but it may instead be linked to the Persian root spand or aspand, or the variant esfand, which may have been, rather, Peganum harmala, a variety of rue, another famously bitter herb. That this particular plant was commonly burned as a protective offering may suggest that its origins lie in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root *spend, meaning 'to perform a ritual' or 'make an offering'. Whether the word was a borrowing from Persian into Greek, or rather from a common ancestor, is unclear.

Absinth (without the 'e') is a spelling variation of absinthe often seen in central Europe. Because so many Bohemian-style products use it, many groups see it as synonymous with bohemian absinth, even though that is not always the case.

Production

The main herbs used are grande wormwood, florence fennel and green anise, often called the 'holy trinity'. Many other herbs may be used as well, such as hyssop, melissa, star anise and petite wormwood (Artemisia pontica or Roman wormwood). Various recipes also include angelica root, Sweet Flag, dittany leaves, coriander, veronica, juniper, nutmeg, and various mountain herbs.

The simple maceration of wormwood in alcohol without distillation produces an extremely bitter drink, due to the presence of the water-soluble absinthine, one of the most bitter substances known. Authentic recipes call for distillation after a primary maceration and before the secondary or 'coloring' maceration. The distillation of wormwood, anise, and Florence fennel first produces a colorless distillate that leaves the alembic at around 82% alcohol. It can be left clear, called a Blanche or la Bleue (used for bootleg Swiss absinthe), or the well-known green colour of the beverage can be imparted either artificially or with chlorophyll by steeping petite wormwood, hyssop, and melissa in the liquid. After this process, the resulting product is reduced with water to the desired percentage of alcohol. Over time and exposure to light, the chlorophyll breaks down, changing the color from emerald green to yellow green to brown. Pre-ban and vintage absinthes are often of a distinct amber colour as a result of this process.

Non-traditional varieties are made by cold-mixing herbs, essences or oils in alcohol, with the distillation process omitted. Often called 'oil mixes', these types of absinthe are not necessarily bad, though they are generally considered to be of lower quality than properly distilled absinthe and often carry a distinct bitter aftertaste.

Alcohol makes up the majority of the drink and its concentration is extremely high, between 45% and 89.9%, though there is no historical evidence that any commercial vintage absinthe was higher than 74%. Given the high strength and low alcohol solubility of many of the herbal components, absinthe is usually not imbibed 'straight' but consumed after a fairly elaborate preparation ritual.

Historically, there were five grades of absinthe: ordinaire, demi-fine, fine, supérieure and Suisse (which does not denote origin), in order of increasing alcoholic strength and production quality. While a supérieure and Suisse would always be naturally colored and distilled; ordinaire and demi-fine could be artificially colored and made from oil extracts. These were only naming guidelines and not an industry standard. Most absinthes contain between 60% and 75% alcohol. It is said to improve materially with storage. In the late 19th century, cheap brands of absinthe were occasionally adulterated by profiteers with copper, zinc, indigo plant, or other dyes to impart the green colour, and with antimony trichloride to produce or enhance the louche effect (see below). It is also thought that the use of cheaper industrial alcohol and poor distillation technique by the manufacturers of cheaper brands resulted in contamination with methanol, fusel alcohol, and similar unwanted distillates. This addition of toxic chemicals is quite likely to have contributed to absinthe's reputation as a hallucination-inducing or otherwise harmful beverage.

Hausgemacht absinthe

German for homemade (often abbreviated HG), also called clandestine, hausgemacht absinthe is home distilled by hobbyists and thus illegal in most countries. Mainly for personal use and not for sale, clandestine absinthe is produced in small quantities allowing experienced distillers to select the best herbs and fine tune each batch. Clandestine production got a major boost after the ban of absinthe when small producers went underground, especially in Switzerland. Although the Swiss produced both vertes and blanches before the ban, clear absinthe (known as La Bleue) became popular as it was easier to hide. Though the Swiss ban was recently lifted, many clandestine distillers have yet to become legal; the authorities believe high taxes on alcohol and the mystique of being underground has kept many from seeking a license. Those that have become legal often still use the 'clandestine' moniker on their products. HG absinthe should not be confused with absinthe kits.

Absinthe kits

There are numerous recipes for homemade absinthe floating around on the Internet, many of which revolve around soaking or mixing a kit or store-bought herbs and wormwood extract with high-proof liquor such as vodka or Everclear. Even though these do-it-yourself kits have gained in popularity, it is simply not possible to produce absinthe without distillation. Absinthe distillation, like the production of any fine liquor, is a science and an art in itself and requires expertise and care to properly manage.

Besides being unpleasant to drink and a pale impression of authentic distilled absinthe, these homemade concoctions can sometimes be poisonous. Many of these recipes call for the usage of liberal amounts of wormwood extract or essence of wormwood in the hopes of increasing the believed psychoactive effects. Consuming essential oils will not only fail to produce a high, but can be very dangerous. Wormwood extract can cause renal failure and death due to excessive amounts of thujone, which in large quantities acts as a convulsive neurotoxin. Essential oil of wormwood should never be consumed straight.

Preparation

Traditionally, absinthe is poured into a glass over which a specially designed slotted spoon is placed. A sugar cube is then deposited in the bowl of the spoon. Ice-cold water is poured or dripped over the sugar until the drink is diluted 3:1 to 5:1. During this process, the components that are not soluble in water, mainly those from anise, fennel and star anise, come out of solution and cloud the drink; the resulting milky opalescence is called the louche (Fr. 'opaque' or 'shady', IPA [luʃ]). The addition of water is important, causing the herbs to 'blossom' and bringing out many of the flavours originally overpowered by the anise. For most people, a good quality absinthe should not require sugar, but it is added according to taste and will also thicken the mouth-feel of the drink.

With increased popularity, the absinthe fountain, a large jar of ice water on a base with spigots, came into use. It allowed a number of drinks to be prepared at once, and with a hands-free drip patrons were able to socialize while louching a glass.

Although many bars served absinthe in standard glasses, a number of glasses were specifically made for absinthe, having a dose line, bulge or bubble in its lower portion to mark how much absinthe should be poured into it (often around 1 oz (30 ml)).

Czech, or Bohemian, absinth

Often called Bohemian-style, Czech-style, anise-free absinthe or just absinth (without the 'e'), Bohemian absinth is produced mainly in the Czech Republic where it gets its Bohemian designation. It contains little to no anise, fennel or other herbs normally found in the more traditional absinthes produced in countries such as France and Switzerland, and can be extremely bitter. Often the only similarities with its traditional counterpart are the use of wormwood and a high alcohol content; for all intents and purposes, it should be considered a completely different product. In most cases, Bohemian-style absinths are not processed by distillation, but are rather high-proof alcohol or vodka which has been cold-mixed with herbal extracts and artificial coloring. Not all absinth produced in the Czech Republic is in the Bohemian style, and there has been a resurgence of traditional absinthe to compete better with the growing world market.

Absinthe (with anise) has been consumed in Czech lands (then part of Austria-Hungary) since the turn of the 20th century, notably by Czech artists, some of whom had an affinity for France, frequenting Prague's Cafe Slavia. Its wider appeal is uncertain. Contemporary Czech producers claim absinth has been produced in the Czech Republic since the 1920s, and that their brands use the same eighty-year-old recipes (e.g. in case of the Hills company, '98% the same'), but there is no independent evidence to support these claims. Since there are currently few legal definitions for absinthe, producers have taken advantage of its romantic associations and psychoactive reputation to market their products under a similar name. Many Bohemian-style producers heavily market thujone content, exploiting the many myths and half truths that surround thujone even though none of these types of absinth contain enough thujone to cause any noticeable effect.

The Czech- or Bohemian-style absinth lacks many of the oils in absinthe that create the louche, and a modern ritual involving fire was created to take this into account. In this ritual, absinth is added to a glass and a sugar cube on a spoon is placed over it. The sugar cube is soaked in absinth then set on fire. The cube is then dropped into the absinth setting it on fire, and water is added until the fire goes out, normally a 1:1 ratio. The crumbling sugar can provide a minor simulation of the louche seen in traditional absinthe, and the lower water ratio enhances effects of the high-strength alcohol.

It is sometimes claimed that this ritual is old and traditional; however, this is false. This method of preparing absinth was in fact first used by Czech manufacturers in the late 1990s and used as a marketing tool, but has since been accepted by many as historical fact, largely because this method has filtered its way into several contemporary movies. Amongst many of the more traditional absinthe enthusiasts, this method of preparing absinthe is looked down upon, and it can negatively affect the flavor of traditional absinthe.

There are a few Czech products that claim to have levels of thujone, which would make them illegal to sell in Europe, as well as the rest of the world. Some of the most expensive Czech products go to the extent of macerating wormwood in the bottle quite similar to an absinthe kit. There is no historical basis for a high thujone level which in fact lends an overwhelming bitterness. Absinthe connoisseurs consider these drinks to be overpriced marketing gimmicks with no historical relationship to real absinthe.

History

The precise origin of absinthe is unclear, although there is evidence of absinthe in several ancient cultures. According to popular legend, however, modern absinthe began as an all-purpose patent remedy created by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Couvet, Switzerland, around 1792 (the exact date varies by account). Ordinaire's recipe was passed on to the Henriod sisters of Couvet, who sold absinthe as a medicinal elixir. In fact, by other accounts, the Henriod sisters may have already been making the elixir before Ordinaire's arrival. In either case, one Major Dubied in turn acquired the formula from the sisters and, in 1797, with his son Marcellin and son-in-law Henry-Louis Pernod, opened the first absinthe distillery, Dubied Père et Fils, in Couvet. In 1805 they built a second distillery in Pontarlier, France, under the new company name Maison Pernod Fils.

Absinthe's popularity grew steadily until the 1840s, when absinthe was given to French troops as a fever preventative. When the troops returned home, they brought their taste for absinthe with them, and it became popular at bars and bistros.

By the 1860s, absinthe had become so popular that in most cafés and cabarets 5 p.m. signalled l’heure verte ('the green hour'). Still, it remained expensive and was favored mainly by the bourgeoisie and eccentric Bohemian artists. By the 1880s, however, the price had dropped significantly, the market expanded, and absinthe soon became the drink of France; by 1910 the French were consuming 36 million litres of absinthe per year.

Ban

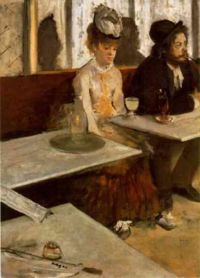

Spurred by the temperance movement and winemakers' associations, absinthe was publicized in connection with several violent crimes supposedly committed under the influence of the drink. This, combined with rising hard liquor consumption due to the wine shortage in France during the 1880s and 1890s, effectively labelled absinthe a social menace. Its critics said that "Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal, provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country." Edgar Degas' 1876 painting L'Absinthe (Absinthe) (now at the Musée d'Orsay) epitomized the popular view of absinthe 'addicts' as sodden and benumbed; Émile Zola described their serious intoxication in his novel L'Assommoir.

Absinthe was banned as early as 1898 in the Congo Free State (later Belgian Congo).

The Lanfray murders were the last straw for absinthe. In 1905, it was reported that Jean Lanfray murdered his family and attempted to kill himself after drinking absinthe. The fact that he was an alcoholic who had drunk considerably after the two glasses of absinthe in the morning was forgotten, and the murders were blamed solely on absinthe. A petition to ban absinthe in Switzerland was quickly signed by over 82,000 people.

Soon thereafter (in 1906), Belgium and Brazil banned the sale and redistribution of absinthe. In Switzerland, the prohibition of absinthe was even written into the constitution in 1907, following a popular initiative. The Netherlands came next, banning absinthe in 1909, followed by the United States in 1912 and France in 1915. Around the same time, Australia banned the liquor too. The prohibition of absinthe in France led to the growing popularity of pastis and ouzo, anise-flavored liqueurs that do not use wormwood. Although Pernod moved their absinthe production to Spain, where absinthe was still legal, slow sales eventually caused it to close down. In Switzerland, it drove absinthe underground. Evidence suggests small home clandestine distillers have been producing absinthe since the ban, focusing on La Bleues as it was easier to hide a clear product. Many countries never banned absinthe, which eventually led to its revival.

Modern revival

In the 1990s an importer, BBH Spirits, realized that there was no UK law prohibiting the sale of absinthe (as it was never banned there) other than the standard regulations governing alcoholic beverages. Hill's Liquere, a Czech Republic distillery founded in 1920, began manufacturing Hill's Absinth, a Bohemian-style absinth, which sparked a modern resurgence in absinthe's popularity.

It had also never been banned in Spain or Portugal, where it continues to be made. Likewise, the former Spanish and Portuguese New World colonies, especially Mexico, allow the sale of absinthe and it has retained popularity through the years.

France never repealed its 1915 law, but in 1988 a law was passed to clarify that only beverages that do not comply with European Union regulations with respect to thujone content, or beverages that call themselves 'absinthe' explicitly, fall under that law. This has resulted in the re-emergence of French absinthes, now labelled spiritueux à base de plantes d'absinthe ('wormwood-based spirits'). Interestingly, as the 1915 law regulates only the sale of absinthe in France but not its production, many manufacturers also produce variants destined for export which are plainly labelled 'absinthe'. La Fée Absinthe, launched in 2000, was the first brand of absinthe distilled and bottled in France since the 1915 ban, initially mainly for export from France, but now one of over twenty French 'spiritueux ... d'absinthe' available in Paris and other French cities.

In December 2000, Australia reclassified it from a prohibited product to a restricted product, requiring a special permit to import or sell absinthe, though it is still available in most bottle shops.

In the Netherlands, this law was successfully challenged by the Amsterdam wine seller Menno Boorsma in July 2004, making absinthe once more legal. Belgium, as part of an effort to simplify its laws, removed its absinthe law on the first of January 2005, citing (as did the Dutch judge) European food regulations as sufficient to render the law unnecessary (and indeed, in conflict with the spirit of the Single European Market).

In Switzerland, the constitutional ban on absinthe was repealed in 2000 during a general overhaul of the national constitution, but the prohibition was written into ordinary law instead. Later that law was also repealed, so from March 2, 2005, absinthe is again legal in its country of origin, after nearly a century of prohibition. Absinthe is now not only sold in Switzerland, but is once again distilled in its Val-de-Travers birthplace, with Kubler and La Clandestine Absinthe among the first new brands to emerge, albeit with an underground heritage.

It is once again legal to produce and sell absinthe in practically every country where alcohol is legal, the major exception being the United States. It is not, however, illegal to possess or consume absinthe in the United States. Despite the legal status of absinthe containing thujone, it can, however, be obtained in a small number of establishments around the United States, notably one in New Orleans, but typically locating those establishments is only achieved via word of mouth.

The only other countries where it is believed that absinthe may not be sold are Denmark, Singapore and Norway. The Norway prohibition is due to the fact that the law forbids the sale of alcohol stronger than 60 percent by volume, which is applicable to most kinds of absinthe.

Cruise ship mystery

In January 2006, a widely published Associated Press wire service article echoed the press' sensationalistic absinthe scare of a century earlier. It was reported that on the night he disappeared, George Allen Smith IV (a Greenwich, Connecticut, man who in July 2005 vanished from aboard the Royal Caribbean's Brilliance of the Seas while on his honeymoon cruise) and other passengers drank a bottle of absinthe. The story noted the modern revival and included quotes from various sources suggesting that absinthe remains a serious and dangerous hallucinogenic drug:

"In large amounts, it would certainly make people see strange things and behave in a strange manner," said Jad Adams, author of the book 'Hideous Absinthe: A History of the Devil in a Bottle'. "It gives people different, unusual ideas that they wouldn't have had of their own accord because of its stimulative effect on the mind."

Absinthe is banned in the United States because of harmful neurological effects caused by a toxic chemical called thujone, said Michael Herndon, spokesman for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The story also noted: "Defenders of the drink say it is safe and its harmful effects a myth." Jad Adams and Ted Breaux were interviewed on MSNBC about this issue. Ted Breaux had this to say:

One thing we know is that absinthe, old and new, does not contain a lot of thujone. And what we know, from certain scientific studies, which have been published in the past year or so, is that, first of all, thujone is not present in any absinthe in sufficient concentration to cause any type of deleterious effects in humans.

Controversy

It was thought that excessive absinthe drinking led to effects which were specifically worse than those associated with overindulgence in other forms of alcohol—which is bound to have been true for some of the less-scrupulously adulterated products, creating a condition called absinthism. Undistilled wormwood essential oil contains a substance called thujone, which is a convulsant and can cause renal failure in extremely high doses, and the supposed ill effects of the drink were blamed on that substance in 19th century studies. Many of these studies were flawed, such as a study by Dr. Magnan in 1869 that exposed a guinea pig to large doses of pure wormwood oil vapor and another to alcohol vapors. The guinea pig exposed to wormwood had seizures while the other did not. Based on this it was concluded absinthe was more dangerous than alcohol. These studies were further taken advantage of as the French word for wormwood is 'absinthe', and it was incorrectly stated that absinthe, the drink, had caused these problems.

Past reports estimated thujone levels in absinthe as high, possibly up to 350 mg/kg. More recent studies have shown that very little of the thujone present in wormwood actually makes it into a properly distilled absinthe, even one recreated using historical recipes and methods. Most proper absinthes, both vintage and modern, are naturally within the EU limits. A recent French distiller has had to add pure essential oil of wormwood to make a 'high thujone' variant of his product. It can remain in higher amounts in oils produced by other methods than distillation, or when wormwood is macerated and not distilled, especially when the plant stems are used, where thujone content is the highest. Tests on mice show an LD50 of around 45 mg thujone per kg of body weight, much higher than what is contained in absinthe and the high amount of alcohol would kill a person many times over before the thujone became a danger. Although direct effects on humans are unknown, many have consumed thujone in higher amounts than present in absinthe through non-controversial sources like common sage and its oil, which can be up to 50% thujone. Long term effects of low wormwood consumption in humans is unknown as well.

The effects of absinthe have been described by artists as mind opening and even hallucinogenic and by prohibitionists as turning good people mad and desolate. Both are exaggerations. Sometimes called 'secondary effects', the most commonly reported experience is a 'clear-headed' feeling of inebriation - a 'lucid drunk', said to be caused by the thujone. The placebo effect and individual reaction to the herbs make these secondary effects subjective and minor compared to the psychoactive effects of alcohol.

A study in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol concluded that a high concentration of thujone in alcohol has negative effects on attention performance. It slowed down reaction time, and subjects concentrated their attention in the central field of vision. Medium doses did not produce an effect noticeably different from plain alcohol. The high dose of thujone in this study was larger than what one can get from current beyond-EU-regulation 'high thujone' absinthe before becoming too drunk to notice, and while the effects of even this high dose were statistically significant in a double blind test, the test subjects themselves could still not reliably identify which samples were the ones containing thujone. As most people describe the effects of absinthe as a more lucid and aware drunk, this suggests that thujone alone is not the cause of these effects. The deleterious effects of absinthe as well as its hallucinogenic properties are a persistent myth often repeated in modern books and scientific journals with no evidence for either.

Cultural impact

The legacy of absinthe as a mysterious, addictive, and mind-altering drink continues to this day. Absinthe has been seen or featured in fine art, movies, video, music and literature. The modern absinthe revival has had an effect on its portrayal. It is often shown as an unnaturally glowing green liquid which is set on fire before drinking, even though traditionally neither is true.

Historical

Numerous artists and writers living in France during the late 19th and early 20th centuries were noted absinthe drinkers and featured absinthe in their works. These include Vincent van Gogh, Édouard Manet, Guy de Maupassant, Arthur Rimbaud and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Later authors and artists would draw from this cultural well including Pablo Picasso, Oscar Wilde and Ernest Hemingway.

Modern

The mystery and illicit quality surrounding the popular view of absinthe has played into modern music, movies and television shows. These depictions vary in their authenticity, often applying dramatic license to depict the drink as everything from aphrodisiac to poison.

Regulations

Currently, most countries do not have a legal definition of absinthe (unlike, for example, Scotch whisky or cognac). Therefore, manufacturers can label a product 'absinthe' or 'absinth', regardless of whether it matches the traditional definition. Due to many countries never banning absinthe, not every country has regulations specifically governing it.

Australia and New Zealand

Bitters can contain a maximum 35 mg/kg thujone, other alcoholic beverages can contain a maximum 10 mg/kg of thujone. In Australia, import and sales require a special permit.

Canada

In Canada, liquor laws are the domain of the provincial governments. British Columbia has no limits on thujone content; Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia allow 10 mg/kg thujone, Québec allows 3 mg per kg (according to the SAQ) and all other provinces do not allow the sale of absinthe containing thujone (although, in Saskatchewan, one can purchase any liquor available in the world upon the purchase of a minimum of one case, usually 12 bottles x 750ml or 8 x 1L). The individual liquor boards must approve each product before it may be sold on shelves, and currently, only Hill's Absinth, Elie-Arnaud Denoix, Pernod, Absente, Versinthe and, in limited release, La Fée Absinthe are approved. Other brands may appear in the future.

European Union

The European Union permits a maximum thujone level of 10 mg/kg in alcoholic beverages with more than 25% ABV, and 35 mg/kg in alcohol labelled as bitters. Member countries regulate absinthe production within this framework. Sale of absinthe is permitted in all EU countries unless they further regulate it.

France

In addition to EU standards, products explicitly called 'absinthe' cannot be sold in France, although they can be produced for export. Absinthe is now commonly labelled as spiritueux à base de plantes d'absinthe ('wormwood-based spirits'). France also regulates Fenchone, a chemical in the herb fennel, to 5 mg/l. This makes many brands of Swiss absinthe illegal without reformatting.

Switzerland

To be legally sold, absinthe must be distilled and either uncolored or naturally colored. In Switzerland, the sale and production of absinthe was prohibited from 1908 to 2005.

United States

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "The importation of Absinthe and any other liquors or liqueurs that contain Artemisia absinthium is prohibited." This runs contrary to FDA regulations, which allow Artemisia species in foods or beverages, but those that contain Artemisia species, white cedar, oak moss, tansy or Yarrow, must be thujone free. Other herbs that contain thujone have no restrictions. For example, sage and sage oil (which can be almost 50% thujone) are on the FDA's list of substances generally recognized as safe.

The prevailing consensus of interpretation of United States law and regulations among American absinthe connoisseurs is that it is probably legal to purchase such a product for personal use in the U.S. It is prohibited to sell items meant for human consumption which contain thujone derived from Artemisia species. (This derives from a Food and Drug Administration regulation, as opposed to a DEA regulation.) Customs regulations specifically forbid the importation of 'absinthe'. Absinthe can be and occasionally is seized by United States Customs if it appears to be for human consumption and can be seized inside the U.S. with a warrant.

A faux-absinthe liquor called Absente, made with southern wormwood ( Artemisia abrotanum) instead of regular wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), is sold legally in the United States and does not contain thujone.

Vanuatu

The Absinthe (Prohibition) Act 1915, passed in the New Hebrides, has never been repealed, and is included in the 1988 Vanuatu consolidated legislation, and contains the following all-encompassing restriction: The manufacture, importation, circulation and sale wholesale or by retail of absinthe or similar liquors in Vanuatu shall be prohibited.