Édouard Manet

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Artists

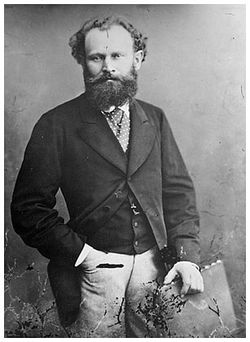

| Édouard Manet | |

portrait by Nadar |

|

| Birth name | Édouard Manet |

| Born | January 23, 1832 Paris |

| Died | April 30, 1883 Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Field | Painting |

| Famous works | The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe), 1863 Olympia , 1863 |

Édouard Manet ( January 23, 1832 – April 30, 1883) was a French painter. One of the first nineteenth century artists to approach modern-life subjects, he was a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism. His early masterworks The Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia engendered great controversy, and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism—today these are considered watershed paintings that mark the genesis of modern art.

Biography

Early life

Édouard Manet was born in Paris in 1832 to an affluent and well connected family. His mother, Eugénie-Desirée Fournier, was the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince, Charles Bernadotte, from whom the current Swedish monarchs are descended. His father, Auguste Manet, was a French judge who expected Édouard to pursue a career in law. His uncle, Charles Fournier, encouraged him to pursue painting and often took young Manet to the Louvre.

From 1850 to 1856, after failing the examination to join the navy, Manet studied under the academic painter Thomas Couture. In his spare time he copied the old masters in the Louvre.

He visited Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, during which time he absorbed the influences of the Dutch painter Frans Hals, and the Spanish artists Diego Velázquez and Francisco José de Goya.

In 1856, he opened his own studio. His style in this period was characterized by loose brush strokes, simplification of details, and the suppression of transitional tones. Adopting the current style of realism initiated by Gustave Courbet, he painted The Absinthe Drinker (1858-59) and other contemporary subjects such as beggars, singers, Gypsies, people in cafés, and bullfights. After his early years, he rarely painted religious, mythological, or historical subjects; examples include his Christ Mocked, now in the Art Institute of Chicago, and Christ with Angels, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Music in the Tuileries

Music in the Tuileries is an early example of Manet's painterly style, inspired by Hals and Velázquez, and it is a harbinger of his life-long interest in the subject of leisure.

While the picture was not regarded as finished by some, the suggested atmosphere imparts a sense of what the Tuileries gardens were like at the time; one may imagine the music and conversation.

Here Manet has depicted his friends, artists, authors, and musicians who take part, and he has included a self-portrait among the subjects.

Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe)

A major early work is The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe). The Paris Salon rejected it for exhibition in 1863, but he exhibited it at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the rejected) later in the year. Emperor Napoleon III had initiated The Salon des Refusés, after the Paris Salon rejected more than 4,000 paintings in 1863.

The painting's juxtaposition of fully-dressed men and a nude woman was controversial, as was its abbreviated, sketch-like handling—an innovation that distinguished Manet from Courbet. At the same time, Manet's composition reveals his study of the old masters, as the disposition of the main figures is derived from Marcantonio Raimondi's engraving Urteil des Paris (c. 1515) after his copy from a drawing by Raphael.

Scholars also cite as an important precedent for Manet's painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, The Tempest which is a famous Renaissance painting by Italian master Giorgione (around 1508). It is housed in the Gallerie dell'Accademia of Venice, Italy. The mysterious and enigmatic painting also features a fully dressed man and a nude female in a rural setting. The man is standing to the left and gazing to the side, apparently at the woman; a partially nude woman, who is sitting in a landscape, and is breastfeeding a baby. While darkening clouds and distant lightening herald an approaching storm. The relationship between the two figures is unclear.

Olympia

As he had in Luncheon on the Grass, Manet again paraphrased a respected work by a Renaissance artist in the painting Olympia ( 1863), a nude portrayed in a style reminiscent of early studio photographs, but whose pose was based on Titian's Venus of Urbino ( 1538).

The painting was controversial partly because the nude is wearing some small items of clothing such as an orchid in her hair, a bracelet, a ribbon around her neck, and mule slippers, all of which accentuated her nakedness. This modern Venus' body is thin, counter to prevailing standards; thin women were not considered attractive at the time, and the painting's lack of idealism rankled. A fully-dressed servant is featured, exploiting the same juxtaposition as in Luncheon on the Grass.

Manet's Olympia also was considered shocking because of the manner in which the subject acknowledges the viewer. She defiantly looks out as her servant offers flowers from one of her male suitors. Although her hand rests on her leg, hiding her pubic area, the reference to traditional female virtue is ironic; a notion of modesty is notoriously absent in this work. The alert black cat at the foot of the bed strikes a rebellious note in contrast to that of the sleeping dog in Titian's portrayal of the goddess in his Venus of Urbino. Manet's uniquely frank (and largely unpopular) depiction of a self-assured prostitute was rejected by the Paris Salon of 1863. At the same time, his notoriety translated to popularity in the French avant-garde community.

As with Luncheon on the Grass, the painting raised the issue of prostitution within contemporary France and the roles of women within society.

Life and times

The roughly painted style and photographic lighting in these works was seen as specifically modern, and as a challenge to the Renaissance works Manet copied or used as source material. His work is considered 'early modern', partially because of the black outlining of figures, which draws attention to the surface of the picture plane and the material quality of paint.

He became friends with the Impressionists Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro, through another painter, Berthe Morisot, who was a member of the group and drew him into their activities. The grand niece of the painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Morisot's paintings first had been accepted in the Salon de Paris in 1864 and she continued to show in the salon for ten years.

Manet became the friend and colleague of Berthe Morisot in 1868. She is credited with convincing Manet to attempt plein air painting, which she had been practicing since she had been introduced to it by another friend of hers, Camille Corot. They had a reciprocating relationship and Manet incorporated some of her techniques into his paintings. In 1874, she become his sister-in-law when she married his brother, Eugene.

Unlike the core Impressionist group, Manet maintained that modern artists should seek to exhibit at the Paris Salon rather than abandon it in favour of independent exhibitions. Nevertheless, when Manet was excluded from the International exhibition of 1867, he set up his own exhibition. His mother worried that he would waste all his inheritance on this project, which was enormously expensive. While the exhibition earned poor reviews from the major critics, it also provided his first contacts with several future Impressionist painters, including Degas.

Although his own work influenced and anticipated the Impressionist style, he resisted involvement in Impressionist exhibitions, partly because he did not wish to be seen as the representative of a group identity, and partly because he preferred to exhibit at the Salon. Eva Gonzalès was his only formal student.

He was influenced by the Impressionists, especially Monet and Morisot. Their influence is seen in Manet's use of lighter colors, but he retained his distinctive use of black, uncharacteristic of Impressionist painting. He painted many outdoor ( plein air) pieces, but always returned to what he considered the serious work of the studio.

Throughout his life, although resisted by art critics, Manet could number as his champions Émile Zola, who supported him publicly in the press, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Charles Baudelaire, who challenged him to depict life as it was. Manet, in turn, drew or painted each of them.

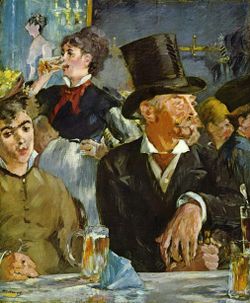

Cafe scenes

Manet's paintings of cafe scenes are observations of social life in nineteenth century Paris. People are depicted drinking beer, listening to music, flirting, reading, or waiting. Many of these paintings were based on sketches executed on the spot. He often visited the Brasserie Reichshoffen on boulevard de Rochechourt, upon which he based At the Cafe in 1878. Several people are at the bar, and one woman confronts the viewer while others wait to be served. Such depictions represent the painted journal of a flâneur. These are painted in a style which is loose, referencing Hals and Velázquez, yet they capture the mood and feeling of Parisian night life. They are painted snapshots of bohemianism, urban working people, as well as some of the bourgeoisie.

In Corner of a Cafe Concert, a man smokes while behind him a waitress serves drinks. In The Beer Drinkers a woman enjoys her beer in the company of a friend. In The Cafe Concert, shown at right, a sophisticated gentleman sits at a bar while a waitress stands resolutely in the background, sipping her drink. In The Waitress, a serving woman pauses for a moment behind a seated customer smoking a pipe, while a ballet dancer, with arms extended as she is about to turn, is on stage in the background.

Manet also sat at the restaurant on the Avenue de Clichy called Pere Lathuille's, which had a garden as well as the dining area. One of the paintings he produced here was, At Pere Lathuille's, in which a man displays an unrequited interest in a woman dining near him.

In Le Bon Bock, a large, cheerful, bearded man sits with a pipe in one hand and a glass of beer in the other, looking straight at the viewer.

Paintings of social activities

Manet also painted the upper class enjoying more formal social activities. In Masked ball at the Opera, Manet shows a lively crowd of people enjoying a party. Men stand with top hats and long black suits while talking to women with masks and costumes. He included portraits of his friends in this picture.

Manet depicted other popular activities in his work. In Racing at Longchamp, an unusual perspective is employed to underscore the furious energy of racehorses as they rush toward the viewer. In Skating Manet shows a well dressed woman in the foreground, while others skate behind her. Always there is the sense of active urban life continuing behind the subject, extending outside the frame of the canvas.

In View of the International Exhibition, soldiers relax, seated and standing, prosperous couples are talking. There is a gardener, a boy with a dog, a woman on horseback—in short, a sample of the classes and ages of the people of Paris.

Politics

The Prints and Drawings Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest) has a watercolour/ gouache (The Barricade) by Manet depicting a summary execution of Communards by Versailles troops based on a lithograph of the Execution of Maximilian. The Execution was one of Manet's largest paintings, and judging by the full-scale preparatory study, one which the painter regarded as most important. Its subject is the execution by Mexican firing squad of a Hapsburg emperor, who had been installed by Napoleon III. As an indictment of formalized slaughter it looks back to Goya, and anticipates Picasso's Guernica.

In January 1871 Manet traveled to Oloron-Sainte-Marie in the Pyrenees. In his absence his friends added his name to the "Féderation des artistes" (see: Courbet) of the Paris Commune. Manet stayed away from Paris, perhaps, until after the Semaine sanglante. In a letter to Berthe Morisot at Cherbourg (June 10,1871) he writes :" We came back to Paris a few days ago...".(the semaine sanglante ended on 28 May).

On 18 March 1871 he wrote to his (confederate) friend Félix Braquemond in Paris about his visit to Bordeaux, the provisory seat of the French National Assembly of the Third French Republic where Emile Zola introduced him to the sites: " I never imagined that France could be represented by such doddering old fools, not excepting that little twit Thiers..." (some colorful language unsuitable at social events followed, see "Manet by himself" 1991/2004). If this could be interpreted as support of the Commune a following letter to Braquemond ( March 21, 1871) expressed his idea more clearly: "Only party hacks and the ambitious, the Henrys of this world following on the heels of the Milliéres, the grotesque imitators of the Commune of 1793..." He knew the communard Lucien Henry to have been a former painters model and Millière, an insurance agent. "What an encouragement all these bloodthirsty caperings are for the arts! But there is at least one consolation in our misfortunes: that we're not politicians and have no desire to be elected as deputies". (the letters are published in Julliet Wilson-Bareau ed "Manet by himself" UK: Times Warner, 2004)

Paris

Manet depicted many scenes of the streets of Paris in his works. The Rue Mosnier Decked with Flags depicts red, white, and blue pennants covering buildings on either side of the street--another painting of the same title features a one-legged man walking with crutches. Again depicting the same street, but this time in a different context, is Rue Monsnier with Pavers, in which men repair the roadway while people and horses move past.

The Railway, widely known as The Gare Saint-Lazare, was painted in 1873. The setting is the urban landscape of Paris in the late nineteenth century. Using his favorite model in his last painting of her, a fellow painter, Victorine Meurent, also the model for Olympia and the Luncheon on the Grass, sits before an iron fence holding a sleeping puppy and an open book in her lap, next to her is a little girl with her back to the painter, who watches a train pass beneath them.

Instead of choosing the traditional natural view as background for an outdoor scene, Manet opts for the iron grating which “boldly stretches across the canvas” (Gay 106). The only evidence of the train is its white cloud of steam. In the distance, modern apartment buildings are seen. This arrangement compresses the foreground into a narrow focus. The traditional convention of deep space is ignored.

When the painting was first exhibited at the official Paris Salon of 1874:

"Visitors and critics found its subject baffling, its composition incoherent, and its execution sketchy. Caricaturists ridiculed Manet’s picture, in which only a few recognized the symbol of modernity that it has become today”(Dervaux 1).

The painting is currently displayed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C..

Late works

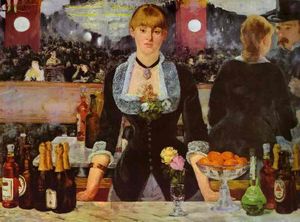

He completed painting his last major work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Le Bar aux Folies-Bergère), in 1882 and it hung in the Salon that year.

In 1875, a French edition of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven included lithographs by Manet and translation by Mallarmé.

In 1881, with pressure from his friend Antonin Proust, the French government awarded Manet the Légion d'honneur.

Private life

In 1863 Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch-born piano teacher of his own age with whom he had been romantically involved for approximately ten years. Leenhoff initially had been employed by Manet's father, Auguste, to teach Manet and his younger brother piano. She also may have been Auguste's mistress. In 1852, Leenhoff gave birth, out of wedlock, to a son, Leon Koella Leenhoff.

After the death of his father in 1862, Manet married Suzanne. Eleven-year-old Leon Leenhoff, whose father may have been either of the Manets, posed often for Manet. Most famously, he is the subject of the Boy with a Sword in 1861.

Death

Manet died of untreated syphilis, which he contracted in his forties. The disease caused him considerable pain and partial paralysis from locomotor ataxia in the years prior to his death.

His left foot was amputated because of gangrene, an operation followed eleven days later by his death. He died at the age of fifty-one in Paris in 1883, and is buried in the Cimetière de Passy in the city.

In 2000, one of his paintings sold for over $20 million.