Pollution

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Environment

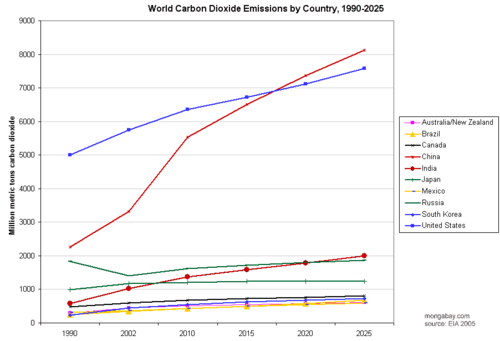

Pollution is the release of environmental contaminants. The U.S., Russia, Mexico, China and Japan are the world leaders in air pollution emissions; however, Canada is the number two country on a per capita basis. The major forms of pollution include:

- air pollution, the release of chemicals and particulates into the atmosphere. Common examples include carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), and nitrogen oxides produced by industry and motor vehicles. Ozone and smog are created as nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons react to sunlight.

- water pollution via surface runoff and leaching to groundwater.

- Soil contamination occurs when chemicals are released by spill or underground storage tank leakage. Among the most significant soil contaminants are hydrocarbons, heavy metals, MTBE, herbicides, pesticides and chlorinated hydrocarbons.

- radioactive contamination, added in the wake of 20th-century discoveries in atomic physics. (See alpha emitters and actinides in the environment.)

- noise pollution, which encompasses roadway noise, aircraft noise, industrial noise as well as high-intensity sonar.

- light pollution, includes light trespass, over-illumination and astronomical interference.

- visual pollution, which can refer to the presence of overhead power lines, motorway billboards, scarred landforms (as from strip mining), open storage of junk or municipal solid waste.

Effects on human health

Pollutants can cause disease, including cancer, lupus, immune diseases, allergies, and asthma. Higher levels of background radiation have led to an increased incidence of cancer and mortality associated with it worldwide. Some illnesses are named for the places where specific pollutants were first formally implicated. One example is Minamata disease, which is caused by organic mercury compounds.

Adverse air quality can kill many organisms including humans. Ozone pollution can cause respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, throat inflammation, chest pain and congestion. Water pollution causes approximately 14,000 deaths per day, mostly due to contamination of drinking water by untreated sewage in developing countries. Oil spills can cause skin irritations and rashes. Noise pollution induces hearing loss, high blood pressure, stress and sleep disturbance.

Regulation and monitoring

United States

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established threshold standards for air pollutants to protect human health on January 1, 1970. One of the ratings chemicals are given is carcinogenicity. In addition to the classification "unknown", designated levels range from non-carcinogen, to likely and known carcinogen. But some scientists have said that the concentrations which most of these levels indicate are far too high and the exposure of people should be less. In 1999, the United States EPA replaced the Pollution Standards Index (PSI) with the Air Quality Index (AQI) to incorporate new PM2.5 and Ozone standards.

Passage of the Clean Water Act amendments of 1977 required strict permitting for any contaminant discharge to navigable waters, and also required use of best management practices for a wide range of other water discharges including thermal pollution.

Passage of the Noise Control Act established mechanisms of setting emission standards for virtually every source of noise including motor vehicles, aircraft, certain types of HVAC equipment and major appliances. It also put local government on notice as to their responsibilities in land use planning to address noise mitigation. This noise regulation framework comprised a broad data base detailing the extent of noise health effects.

The U.S. has a maximum fine of US$25,000 for dumping toxic waste. However, many large manufacturers decline to dispute violations, as they can easily afford this small fine. The state of California Cal/EPA Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) has maintained an independent list of substances with product labeling requirements as part of Proposition 65 since 1986.

Europe

Generally the European countries lagged significantly behind the United States in meaningful environmental regulation, including air quality standards, water quality standards, soil contamination cleanup, indoor air quality and noise regulations. Despite this, European pollution output is far lower than that of the USA. In the year 2000, UK Air Quality Regulations were established and they were further amended in 2002. There has also been British harmonization with EU regulations.

The EU is presently entertaining use of the carcinogen MTBE as a widespread gasoline additive, a chemical which has been in the process of phaseout in the U.S. for over a decade.

The United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, it took until the 1840s to bring onto the statute books legislation to control water pollution. It was extended to all rivers and coastal water by 1961. However, currently the clean up of historic contamination is controlled under a specific statutory scheme found in Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (Part IIA), as inserted by the Environment Act 1995, and other ‘rules’ found in regulations and statutory guidance. The Act came into force in England in April 2000.

Pollution of controlled waters

The second part of the statutory definition of contaminated land covers where polluting material is entering or likely to enter controlled waters. The statutory guidance provides that the likelihood of the entry of the contaminant is to be assessed on the balance of probabilities. The definition of contaminated land within Part IIA (in relation to pollution of controlled waters), in that the contamination will need to be deemed to be significant.

There is currently no guidance available on what may, or may not, be significant pollution of controlled waters except that one that is based upon risk is considered to be appropriate. This approach has already been taking place throughout the industry and widely accepted by the regulators as a means of assessing the significance of groundwater contamination. As such pollutant linkages with respect to ground and surface water targets/receptors are considered in a similar manner to that for significant harm.

Soil contamination

Two sources of published generic guidance are currently commonly used in the UK:

- The Contaminated Land Exposure Assessment (CLEA) Guidelines

- The Dutch Standards.

Guidance by the Inter Departmental Committee for the Redevelopment of Contaminated Land (ICRCL) has been formally withdrawn by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), for use as a prescriptive document to determine the potential need for remediation or further assessment. Therefore, no further reference is made to these former guideline values.

Other generic guidance that may be referred to (to put the concentration of a particular contaminant in context), include the United States EPA Region 9 Preliminary Remediation Goals (US PRGs), the US EPA Region 3 Risk Based Concentrations (US EPA RBCs) and National Environment Protection Council of Australia Guideline on Investigation Levels in Soil and Groundwater.

The CLEA model published by DEFRA and the Environment Agency (EA) in March 2002 sets a framework for the appropriate assessment of risks to human health from contaminated land, as required by Part IIA of the Environmental Protection Act 1990. As part of this framework, generic Soil Guideline Values (SGVs) have currently been derived for ten contaminants to be used as “intervention values”. These values should not be considered as remedial targets but values above which further detailed assessment should be considered.

Three sets of CLEA SGVs have been produced for three different land uses, namely:

- residential (with and without plant uptake)

- allotments

- commercial/industrial

It is intended that the SGVs replace the former ICRCL values. It should be noted that the CLEA SGVs relate to assessing chronic (long term) risks to human health and do not apply to the protection of ground workers during construction, or other potential receptors such as groundwater, buildings, plants or other ecosystems. The CLEA SGVs are not directly applicable to a site completely covered in hardstanding, as there is no direct exposure route to contaminated soils.

To date, the first ten of fifty-five contaminant SGVs have been published, for the following: arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, inorganic mercury, nickel, selenium ethyl benzene, phenol and toluene. Draft SGVs for benzene, naphthalene and xylene have been produced but their publication is on hold. Toxicological data (Tox) has been published for each of these contaminants as well as for benzo[a]pyrene, benzene, dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs, naphthalene, vinyl chloride, 1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane and 1,1,1,2 tetrachloroethane, 1,1,1 trichloroethane, tetrachloroethene, carbon tetrachloride, 1,2-dichloroethane, trichloroethene and xylene. The SGVs for ethyl benzene, phenol and toluene are dependent on the soil organic matter (SOM) content (which can be calculated from the total organic carbon (TOC) content). As an initial screen the SGVs for 1% SOM are considered to be appropriate.

Groundwater

The Water Supply Regulations (WSR) 1989 value, the UK Freshwater Environmental Quality Standards (FEQS), Dutch Intervention Values (DIV), World Health Organisation (WHO) Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality 2004 and USEPA Drinking Water Advisory are used in the UK as initial conservative screening values to assess whether groundwater contamination requires further assessment in terms of the wider groundwater/surface water environment. Where further assessment is considered necessary, this is undertaken qualitatively or quantitatively (if considered necessary or appropriate)on a Site specific basis using the Environment Agency (EA) Spreadsheets associated with R & D Paper 20, “Methodology for the Derivation of Remedial Targets for Soil and Groundwater to Protect Water Resources, Version 2.2” or similar.

China

China's rapid industrialization has substantially increased pollution. China has some relevant regulations: the 1979 Environmental Protection Law, which was largely modelled on U.S. legislation. But the environment continues to deteriorate. Twelve years after the law, only one Chinese city was making an effort to clean up its water discharges. This indicates that China is about 30 years behind the U.S. schedule of environmental regulation and 10 to 20 years behind Europe.

International

The Kyoto Protocol is an amendment to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), an international treaty on global warming. It also reaffirms sections of the UNFCCC. Countries which ratify this protocol commit to reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide and five other greenhouse gases, or engage in emissions trading if they maintain or increase emissions of these gases. A total of 141 countries have ratified the agreement. Notable exceptions include the United States and Australia, who have signed but not ratified the agreement. The stated reason for the United States not ratifying is the exemption of large emitters of greenhouse gases who are also developing countries, like China and India.

History

Prehistory

Humankind has had some effect upon the natural environment since the paleolithic era during which the ability to generate fire was acquired. In the iron age, the use of tooling led to the practice of metal grinding on a small scale and resulted in minor accumulations of discarded material probably easily dispersed without too much impact. Human wastes would have polluted rivers or water sources to some degree. However, these effects could be expected predominantly to be dwarfed by the natural world.

Ancient cultures

The first advanced civilizations of China, Egypt, Persia, Greece and Rome increased the use of water for primitive industrial processes, increasingly forged metal and created fires of wood and peat for more elaborate purposes (for example, bathing, heating). Still, at this time the scale of higher activity did not disrupt ecosystems or greatly alter air or water quality.

Middle Ages

The dark ages and early Middle Ages were a great boon for the environment, in that industrial activity fell, and population levels did not grow rapidly. Toward the end of the Middle Ages populations grew and concentrated more within cities, creating pockets of readily evident contamination. In certain places air pollution levels were recognizable as health issues, and water pollution in population centers was a serious medium for disease transmission from untreated human waste.

Since travel and widespread information were less common, there did not exist a more general context than that of local consequences in which to consider pollution. Foul air would have been considered a nuissance and wood, or eventually, coal burning produced smoke, which in sufficient concentrations could be a health hazard in proximity to living quarters. Septic contamination or poisoning of a clean drinking water source was very easily fatal to those who depended on it, especially if such a resource was rare. Superstitions predominated and the extent of such concerns would probably have been little more than a sense of moderation and an avoidance of obvious extremes.

First recognition

But gradually increasing populations and the proliferation of basic industrial processes saw the emergence of a civilization that began to have a much greater collective impact on its surroundings. It was to be expected that the beginnings of environmental awareness would occur in the more developed cultures, particularly in the densest urban centers. The first medium warranting official policy measures in the emerging western world would be the most basic: the air we breathe.

King Edward I of England banned the burning of sea-coal by proclamation in London in 1272, after its smoke had become a problem. But the fuel was so common in England that this earliest of names for it was acquired because it could be carted away from some shores by the wheelbarrow. Air pollution would continue to be a problem there, especially later during the industrial revolution, and extending into the recent past with the Great Smog of 1952. This same city also recorded one of the earlier extreme cases of water quality problems with the Great Stink on the Thames of 1858, which led to construction of the London sewerage system soon afterward.

It was the industrial revolution that gave birth to environmental pollution as we know it today. The emergence of great factories and consumption of immense quantities of coal and other fossil fuels gave rise to unprecedented air pollution and the large volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the growing load of untreated human waste. Chicago and Cincinnati were the first two American cities to enact laws ensuring cleaner air in 1881. Other cities followed around the country until early in the 20th century, when the short lived Office of Air Pollution was created under the Department of the Interior. Extreme smog events were experienced by the cities of Los Angeles and Donora, Pennsylvania in the late 1940s, serving as another public reminder.

Modern awareness

Pollution began to draw major public attention in the United States between the mid-1950s and early 1970s, when Congress passed the Noise Control Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Bad bouts of local pollution helped increase consciousness. PCB dumping in the Hudson River resulted in a ban by the EPA on consumption of its fish in 1974. Long-term dioxin contamination at Love Canal starting in 1947 became a national news story in 1978 and led to the Superfund legislation of 1980. Legal proceedings in the 1990s helped bring to light Chromium-6 releases in California--the champions of whose victims, such as Erin Brockovich, became famous. The pollution of industrial land gave rise to the name brownfield, a term now common in city planning. DDT was banned in most of the developed world after the publication of " Silent Spring".

The development of nuclear science introduced radioactive contamination, which can remain lethally radioactive for hundreds of thousands of years. Lake Karachay, named by the Worldwatch Institute as the "most polluted spot" on earth, served as a disposal site for the Soviet Union thoroughout the 1950s and 1960s. Nuclear weapons continued to be tested in the Cold War, sometimes near inhabited areas, especially in the earlier stages of their development. The toll on the worst-affected populations and the growth since then in understanding about the critical threat to human health posed by radioactivity has also been a prohibitive complication associated with nuclear power. Though extreme care is practiced in that industry, the potential for disaster suggested by incidents such as those at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl pose a lingering specter of public mistrust. One legacy of nuclear testing before most forms were banned has been significantly raised levels of background radiation.

International catastrophes such as the wreck of the Amoco Cadiz oil tanker off the coast of Brittany in 1978 and the Bhopal industrial disaster in 1984 have demonstrated the universality of such events and the scale on which efforts to address them needed to engage. The borderless nature of the atmosphere and oceans inevitably resulted in the implication of pollution on a planetary level with the issue of global warming. Most recently the term persistent organic pollutant (POP) has come to describe a group of chemicals such as PBDEs and PFCs among others. Though their effects remain somewhat less well understood owing to a lack of experimental data, have been detected in various ecological habitats far removed from industrial activity such as the arctic, demonstrating bioaccumulation after only a relatively brief period of widespread use.

Growing evidence of local and global pollution and an increasingly informed public over time have given rise to environmentalism and the environmental movement, which generally seek to limit human impact on the environment.

Perspectives

The earliest precursor of pollution generated by life forms would have been a natural function of their existence. The attendant consequences on viability and population levels fell within the sphere of natural selection. These would have included the demise of a population locally or ultimately, species extinction. Processes that were untenable would have resulted in a new balance brought about by changes and adaptations. At the extremes, for any form of life, consideration of pollution is superseded by that of survival.

For mankind, the factor of technology is a distinguishing and critical consideration, both as an enabler and an additional source of byproducts. Short of survival, human concerns include the range from quality of life to health hazards. Since science holds experimental demonstration to be definitive, modern treatment of toxicity or environmental harm involves defining a level at which an effect is observable. Common examples of fields where practical measurement is crucial include automobile emissions control, industrial exposure (eg OSHA PELs), toxicology (eg LD50), and medicine (eg medication and radiation doses).

"The solution to pollution is dilution", is a dictum which summarizes a traditional approach to pollution management whereby sufficiently diluted pollution is not harmful. It is well-suited to some other modern, locally-scoped applications such as laboratory safety procedure and hazardous material release emergency management. But it assumes that the dilutant is in virtually unlimited supply for the application or that resulting dilutions are acceptable in all cases.

Such simple treatment for environmental pollution on a wider scale might have had greater merit in earlier centuries when physical survival was often the highest imperative, human population and densities were lower, technologies were simpler and their byproducts more benign. But these are often no longer the case. Furthermore, advances have enabled measurement of concentrations not possible before. The use of statistical methods in evaluating outcomes has given currency to the principle of probable harm in cases where assessment is warranted but resorting to deterministic models is impractical or unfeasible. In addition, consideration of the environment beyond direct impact on human beings has gained prominence.

Yet in the absence of a superseding principle, this older approach predominates practices throughout the world. It is the basis by which to gauge concentrations of effluent for legal release, exceeding which penalties are assessed or restrictions applied. The regressive cases are those where a controlled level of release is too high or, if enforceable, is neglected. Migration from pollution dilution to elimination in many cases is confronted by challenging economical and technological barriers.

Controversy

Industry and concerned citizens have battled for decades over the significance of various forms of pollution. Salient parameters of these disputes are whether:

- a given pollutant affects all people or simply a genetically vulnerable set.

- an effect is only specific to certain species.

- whether the effect is simple, or whether it causes linked secondary and tertiary effects, especially on biodiversity

- an effect will only be apparent in the future and is presently negligible.

- the threshold for harm is present.

- the pollutant is of direct harm or is a precursor.

- employment or economic prosperity will suffer if the pollutant is abated.

Blooms of algae and the resultant eutrophication of lakes and coastal ocean is considered pollution when it is caused by nutrients from industrial, agricultural, or residential runoff in either point source or nonpoint source form (see the article on eutrophication for more information).

Heavy metals such as lead and mercury have a role in geochemical cycles and they occur naturally. These metals may also be mined and, depending on their processing, may be released disruptively in large concentrations into an environment they had previously been absent from. Just as the effect of anthropogenic release of these metals into the environment may be considered 'polluting', similar environmental impacts could also occur in some areas due to either autochthonous or historically 'natural' geochemical activity.

Carbon dioxide, while vital for photosynthesis, is sometimes referred to as pollution, because raised levels of the gas in the atmosphere affect the Earth's climate. See global warming for an extensive discussion of this topic. Disruption of the environment can also highlight the connection between areas of pollution that would normally be classified separately, such as those of water and air. Recent studies have investigated the potential for long-term rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide to cause slight but critical increases in the acidity of ocean waters, and the possible effects of this on marine ecosystems.