Kyoto Protocol

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Environment

|

|||

| Kyoto Protocol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Opened for signature | December 11, 1997 in Kyoto, Japan | ||

| Entered into force | February 16, 2005. | ||

| Conditions for entry into force | 55 parties and at least 55% CO2 1990 emissions by UNFCCC Annex I parties. | ||

| Parties | 166 countries and other governmental entities (as of October 2006) | ||

The Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is an amendment to the international treaty on climate change, assigning mandatory targets for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to signatory nations.

Description

The Kyoto Protocol is an agreement made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Countries that ratify this protocol commit to reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide and five other greenhouse gases, or engage in emissions trading if they maintain or increase emissions of these gases.

The Kyoto Protocol now covers more than 160 countries globally and over 55% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

At its heart, Kyoto establishes the following principles:

- Kyoto is underwritten by governments and is governed by global legislation enacted under the UN’s aegis

- Governments are separated into two general categories: developed countries, referred to as Annex 1 countries (who have accepted GHG emission reduction obligations); and developing countries, referred to as Non-Annex 1 countries (who have no GHG emission reduction obligations).

- Any Annex 1 country that fails to meet its Kyoto target will be penalized by having its reduction targets decreased by 30% in the next period.

- By 2008-2012, Annex 1 countries have to reduce their GHG emissions by around 5% below their 1990 levels (for many countries, such as the EU member states, this corresponds to some 15% below their expected GHG emissions in 2008). Reduction targets expire in 2013.

- Kyoto includes "flexible mechanisms" which allow Annex 1 economies to meet their GHG targets by purchasing GHG emission reductions from elsewhere. These can be bought either from financial exchanges (such as the new EU Emissions Trading Scheme) or from projects which reduce emissions in non-Annex 1 economies under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), or in other Annex-1 countries under the JI.

- Only CDM Executive Board-accredited Certified Emission Reductions (CER) can be bought and sold in this manner. Under the aegis of the UN, Kyoto established this Bonn-based Clean Development Mechanism Executive Board to assess and approve projects (“CDM Projects”) in Non-Annex 1 economies prior to awarding CERs. (A similar scheme called “Joint Implementation” or “JI” applies in transitional economies mainly covering the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe).

What this means in practice is that Non-Annex 1 economies have no GHG emission restrictions, but when a GHG emission reduction project (a “GHG Project”) is implemented in these countries, that GHG Project will receive Carbon Credits which can be sold to Annex 1 buyers.

The Kyoto linking mechanisms are in place for two main reasons:

- the cost of complying with Kyoto is prohibitive for many Annex 1 countries (especially those countries, such as Japan or the Netherlands for example, with highly efficient, low GHG polluting industries, and high prevailing environmental standards). Kyoto therefore allows these countries to purchase Carbon Credits instead of reducing GHG emissions domestically; and,

- this is seen as a means of encouraging Non-Annex 1 developing economies to reduce GHG emissions since doing so is now economically viable because of the sale of Carbon Credits.

All the Annex 1 economies have established Designated National Authorities to manage their GHG portfolios under Kyoto. Countries including Japan, Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain and many more, are actively promoting government carbon funds and supporting multilateral carbon funds intent on purchasing Carbon Credits from Non-Annex 1 countries. These government organizations are working closely with their major utility, energy, oil & gas and chemicals conglomerates to try to acquire as many GHG Certificates as cheaply as possible.

Virtually all of the Non-Annex 1 countries have also set up their own Designated National Authorities to manage the Kyoto process (and specifically the “CDM process” whereby these host government entities decide which GHG Projects they do or do not wish to support for accreditation by the CDM Executive Board).

The objectives of these opposing groups are quite different. Annex 1 entities want Carbon Credits as cheaply as possible, whilst Non-Annex 1 entities want to maximise the value of Carbon Credits generated from their domestic GHG Projects.

Objectives

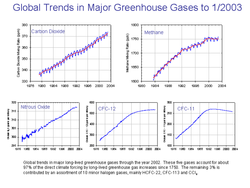

The objective is the "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system."

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted an average global rise in temperature of 1.4° C (2.5° F) to 5.8 °C (10.4° F) between 1990 and 2100). Current estimates indicate that even if successfully and completely implemented, the Kyoto Protocol will reduce that increase by somewhere between 0.02 °C and 0.28 °C by the year 2050 (source: Nature, October 2003).

Proponents also note that Kyoto is a first step as requirements to meet the UNFCCC will be modified until the objective is met, as required by UNFCCC Article 4.2(d).

Status of the agreement

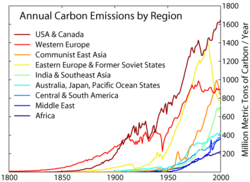

The treaty was negotiated in Kyoto, Japan in December 1997, opened for signature on March 16, 1998, and closed on March 15, 1999. The agreement came into force on February 16, 2005 following ratification by Russia on November 18, 2004. As of October 2006, a total of 166 countries and other governmental entities have ratified the agreement (representing over 61.6% of emissions from Annex I countries). Notable exceptions include the United States and Australia. Other countries, like India and China, which have ratified the protocol, are not required to reduce carbon emissions under the present agreement despite their relatively large populations.

According to article 25 of the protocol, it enters into force "on the ninetieth day after the date on which not less than 55 Parties to the Convention, incorporating Parties included in Annex I which accounted in total for at least 55% of the total carbon dioxide emissions for 1990 of the Parties included in Annex I, have deposited their instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession." Of the two conditions, the "55 parties" clause was reached on May 23, 2002 when Iceland ratified. The ratification by Russia on 18 November 2004 satisfied the "55%" clause and brought the treaty into force, effective February 16, 2005.

Details of the agreement

According to a press release from the United Nations Environment Programme:

- "The Kyoto Protocol is an agreement under which industrialised countries will reduce their collective emissions of greenhouse gases by 5.2% compared to the year 1990 (but note that, compared to the emissions levels that would be expected by 2010 without the Protocol, this target represents a 29% cut). The goal is to lower overall emissions of six greenhouse gases - carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, HFCs, and PFCs - calculated as an average over the five-year period of 2008-12. National targets range from 8% reductions for the European Union and some others to 7% for the US, 6% for Japan, 0% for Russia, and permitted increases of 8% for Australia and 10% for Iceland."

It is an agreement negotiated as an amendment to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, which was adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992). All parties to the UNFCCC can sign or ratify the Kyoto Protocol, while non-parties to the UNFCCC cannot. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted at the third session of the Conference of Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan.

Most provisions of the Kyoto Protocol apply to developed countries, listed in Annex I to the UNFCCC.

Common but differentiated responsibility

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed to a set of a "common but differentiated responsibilities." The parties agreed that

- The largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries;

- Per capita emissions in developing countries are still relatively low;

- The share of global emissions originating in developing countries will grow to meet their social and development needs.

In other words, China, India, and other developing countries were exempt from the requirements of the Kyoto Protocol because they were not the main contributors to the greenhouse gas emissions during the industrialization period that is believed to be causing today's climate change.

However, critics of Kyoto argue that China, India, and other developing countries will soon be the top contributors to greenhouse gases. Also, without Kyoto restrictions on these countries, industries in developed countries will be driven towards these non-restricted countries, thus there is no net reduction in carbon.

Financial commitments

The Protocol also reaffirms the principle that developed countries have to pay, and supply technology to other countries for climate-related studies and projects. This was originally agreed in the UNFCCC.

Emissions trading

Kyoto is a ‘cap and trade’ system that imposes national caps on the emissions of Annex I countries. On average, this cap requires countries to reduce their emissions 5.2% below their 1990 baseline over the 2008 to 2012 period. Although these caps are national-level commitments, in practice most countries will devolve their emissions targets to individual industrial entities, such as a power plant or paper factory. This is the case today in the EU, and other countries may follow suit in time.

This means that the ultimate buyers of Credits are often individual companies that expect their emissions to exceed their quota (their Assigned Amount Units, Allowances for short). Typically, they will purchase Credits directly from another party with excess allowances, from a broker, from a JI/CDM developer, or on an exchange.

National governments, some of whom may not have devolved responsibility for meeting Kyoto targets to industry, and that have a net deficit of Allowances, will buy credits for their own account, mainly from JI/CDM developers. These deals are occasionally done directly through a national fund or agency, as in the case of the Dutch government’s ERUPT programme, or via collective funds such as the World Bank’s Prototype Carbon Fund (PCF). The PCF, for example, represents a consortium of six governments and 17 major utility and energy companies on whose behalf it purchases Credits.

Since Carbon Credits are tradeable instruments with a transparent price, financial investors have started buying them for pure trading purposes. This market is expected to grow substantially, with banks, brokers, funds, arbitrageurs and private traders eventually participating. Emissions Trading PLC, for example, was floated on the London Stock Exchange's AiM market in 2005 with the specific remit of investing in emissions instruments.

Although Kyoto created a framework and a set of rules for a global carbon market, there are in practice several distinct schemes or markets in operation today, with varying degrees of linkages among them.

Kyoto enables a group of several Annex I countries to join together to create a so-called ‘bubble’, or a cluster of countries that is given an overall emissions cap and is treated as a single entity for compliance purposes. The EU elected to be treated as such a group, and created the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) as a market-within-a-market. The ETS’s currency is an EUA (EU Allowance). The scheme went into operation on 1 January 2005, although a forward market has existed since 2003.

The UK established its own learning-by-doing voluntary scheme, the UK ETS, which runs from 2002 through 2006. This market will exist alongside the EU’s scheme, and participants in the UK scheme have the option of applying to opt out of the first phase of the EU ETS, which lasts through 2007.

Canada and Japan will establish their own internal markets in 2008, and it is very likely that they will link directly into the EU ETS. Canada’s scheme will probably include a trading system for large point sources of emissions and for the purchase of large amounts of outside credits. The Japanese plan will probably not include mandatory targets for companies, but will also rely on large-scale purchases of external credits.

Next to the EU ETS, the most important sources of credits are the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and the Joint Implementation (JI) mechanism. The CDM allows the creation of new Carbon Credits by developing emission reduction projects in Non-Annex I countries, while JI allows project-specific credits to be converted from existing credits in Annex I countries. CDM projects produce Certified Emission Reductions (CERs), and JI projects produce Emission Reduction Units (ERUs). CERs are valid for meeting EU ETS obligations as of now, and ERUs will become similarly valid from 2008 (although individual countries may choose to limit the number and source of CER/JIs they will allow for compliance purposes starting from 2008). CERs/ERUs are overwhelmingly bought from project developers by funds or individual entities, rather than being exchange-traded like EUAs.

Since the creation of these instruments is subject to a lengthy process of registration and certification by the UN, and the projects themselves require several years to develop, this market is at this point almost completely a forward market where purchases are made at a deep discount to their equivalent currency, the EUA, and are almost always subject to certification and delivery (although up-front payments are sometimes made). According to IETA, the market value of CDM/JI credits transacted in 2004 was EUR 245m; it is estimated that more than EUR 620m worth of credits were transacted in 2005.

Several non-Kyoto carbon markets are already in existence as well, and these are likely to grow in importance and numbers in the coming years. These include the New South Wales Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) in the United States, the Chicago Climate Exchange, the State of California’s recent initiative to reduce emissions, the commitment of 131 US mayors to adopt Kyoto targets for their cities, and the State of Oregon’s emissions abatement program.

Taken together, these initiatives point to a series of linked markets, rather than a single carbon market. The common theme across most of them is the adoption of market-based mechanisms centered on Carbon Credits that represent a reduction of CO2 emissions. The fact that most of these initiatives have similar approaches to certifying their credits makes it conceivable that Carbon Credits in one market may in the long run be tradeable in most other schemes. This would broaden the current carbon market far more than the current focus on the CDM/JI and EU ETS domains. An obvious precondition, however, is a realignment of penalties and fines to similar levels, since these create an effective ceiling for each market.

Revisions

The protocol left several issues open to be decided later by the Conference of Parties (COP). COP6 attempted to resolve these issues at its meeting in the Hague in late 2000, but was unable to reach an agreement due to disputes between the European Union on the one hand (which favoured a tougher agreement) and the United States, Canada, Japan and Australia on the other (which wanted the agreement to be less demanding and more flexible).

In 2001, a continuation of the previous meeting (COP6bis) was held in Bonn where the required decisions were adopted. After some concessions, the supporters of the protocol (led by the European Union) managed to get Japan and Russia in as well by allowing more use of carbon dioxide sinks.

COP7 was held from 29 October 2001 – 9 November 2001 in Marrakech to establish the final details of the protocol.

The first Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (MOP1) was held in Montreal from November 28 to December 9, 2005, along with the 11th conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP11). See United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Enforcement

If the Enforcement Branch determines that an Annex I country is not in compliance with its emissions targets, then that country is required to make up the difference plus an additional 30 percent. In addition, that country will be suspended from making transfers under an emissions trading program.

Current positions of governments

Position of Australia

Pollution and emissions are not the constitutional responsibility of the Federal Government of Australia. Section 52 of the Constitution leaves these matters in the hands of the States. Despite the fact that Australia was at the time of the negotiation already one of the biggest emitters on a per capita basis (albeit the lowest on a per square kilometre basis due to low overall population density), the country was granted a target of 8% increase. This is because Australia used its relative smallness as a negotiation tool while other big players were negotiating. The result of the negotiation was reported in the Australian media as being to Australia's advantage .

Nonetheless, the Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, has refused to ratify the Agreement and has argued that the protocol would cost Australians jobs, due to countries with booming economies and massive populations such as China and India not having any reduction obligations. By way of example, if Australia were to shut down all of its coal fired power stations, within 12 months China would have produced so much extra pollution because of its industrial growth that it would have negated the shutting down of those Australian power stations . Further, the Government takes the view that Australia is already doing enough to cut emissions; the Australian government has recently pledged $300 million over the next three years to reduce Greenhouse gas emissions. The Federal Opposition, the Australian Labor Party, is in full support of the protocol and it is currently a heavily debated issue within the political establishment. The opposition claims ratifying the protocol is a "risk free" prospect as they claim Australia would already be meeting the obligations the protocol would impose . This claim relies heavily on changes to land clearing policies that can only occur once, while ongoing emission sources have all increased substantially. As of 2005, Australia was the world's largest emitter per capita of greenhouse gases.

The Australian government, along with the United States, agreed to sign the Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate at the ASEAN regional forum on 28 July 2005. Furthermore, the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) commenced The NSW Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme (GGAS). This mandatory greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme commenced on 1 January 2003 and is currently being trialed by the state government in NSW alone. Uniquely this scheme allows Accredited Certificate Providers (ACP) to trade emissions from householders in the state. As of 2006 the scheme is still in place despite Prime Minister John Howard's clear dismissal of emissions trading as a credible solution to climate change. Following the example of NSW, the National Emissions Trading Scheme (NETS) has been established as an initiative of State and Territory Governments of Australia, all of which have Labor Party governments. The focus of NETS is to bring into existence an intra-Australian carbon trading scheme and to coordinate policy developments to this end. According to the Constitution of Australia, environmental matters are under the jurisdiction of the States, and the NETS is intended to facilitate ratification of the Kyoto Protocol by the Labor Party if they are elected to government in the 2007 Federal Elections.

Position of Canada

On December 17, 2002, Canada ratified the treaty. While numerous polls have shown support for the Kyoto protocol at around 70%, there is still some opposition, particularly by some business groups, non-governmental climate scientists and energy concerns, using arguments similar to those being used in the US. There is also a fear that since US companies will not be affected by the Kyoto Protocol that Canadian companies will be at a disadvantage in terms of trade. In 2005, the result was limited to an ongoing "war of words", primarily between the government of Alberta (Canada's primary oil and gas producer) and the federal government. There were even fears that Kyoto could threaten national unity, specifically with regard to Alberta.

After January 2006, the Liberal government was replaced by a Conservative minority government under Stephen Harper, who previously has expressed opposition to Kyoto. During the election campaign, Harper stated he wanted to move beyond the Kyoto debate by establishing different environmental controls. Rona Ambrose, who considers the emission trading concept to be flawed, replaced Stéphane Dion as the environment minister. Dion even admitted that a future Liberal government would not be able to meet its Kyoto commitment of reducing greenhouse gas emissions below 1990 levels, though he has more recently stated that his plan as a contender for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, would be able to meet Canada's Kyoto commitments.

The biggest challenge facing the new Conservative government was inheriting the ineffective policies of the previous government. As of 2003, the Liberal federal government had spent 3.7 billion dollars on Kyoto programmes, resulting in CO2 emissions 35 per cent above 1990 levels. And so on April 25, 2006, Ambrose announced that Canada would have no chance of meeting its targets under Kyoto, and would look to participate in U.S. sponsored Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate. "We've been looking at the Asia-Pacific Partnership for a number of months now because the key principles around [it] are very much in line with where our government wants to go," Ambrose told reporters . On May 2, 2006, it was reported that environmental funding designed to meet the Kyoto standards has been cut, while the Harper government develops a new plan to take its place.

A private member's bill, has been put forth by Pablo Rodriguez, Liberal Member of Parliament for the riding of Honoré—Mercier. The bill aims to force the minority government of Stephen Harper to "ensure that Canada meets its global climate change obligations under the Kyoto Protocol." With the support of the Liberals, the New Democratic Party and the Bloc Québécois, and with the current minority situation, this bill has a fair chance of being passed - despite the fact that private member's bills rarely succeed in becoming law. If passed, the bill would force Harper's government to form a Climate Change Plan within 6 months of the bill receiving royal assent.

Position of China

China insists that the gas emissions level of any given country is a multiplication of its per capita emission and its population. Because China has emplaced population control measures while maintaining low emissions per capita, it claims it should therefore in both the above aspects be considered a contributor to the world environment. China considers the criticism of its energy policy unjust.

Position of the European Union

On May 31, 2002, all fifteen then-members of the European Union deposited the relevant ratification paperwork at the UN. The EU produces around 22% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and has agreed to a cut, on average, by 8% from 1990 emission levels. The EU has consistently been one of the major supporters of the Kyoto Protocol, negotiating hard to get wavering countries on board.

In December, 2002, the EU created a emissions trading system in an effort to meet these tough targets. Quotas were introduced in six key industries: energy, steel, cement, glass, brick making, and paper/cardboard. There are also fines for member nations that fail to meet their obligations, starting at €40/ton of carbon dioxide in 2005, and rising to €100/ton in 2008. Current EU projections suggest that by 2008 the EU will be at 4.7% below 1990 levels.

The position of the EU is not without controversy in Protocol negotiations, however. One criticism is that, rather than reducing 8%, all the EU member countries should cut 15% as the EU insisted a uniform target of 15% for other developed countries during the negotiation while allowing itself to share a big reduction in the former East Germany to meet the 15% goal for the entire EU. Also, emission levels of former Warsaw Pact countries who now are members of the EU have already been reduced as a result of their economic restructuring. This may mean that the region's 1990 baseline level is inflated compared to that of other developed countries, thus giving European economies a potential competitive advantage over the U.S.

Both the EU (as the European Community) and its member states are signatories to the Kyoto treaty.

Position of Germany

On June 28, 2006, the German government announced it would exempt its coal industry from requirements under the Kyoto agreement. Claudia Kemfert, an energy professor at the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin said, "For all its support for a clean environment and the Kyoto Protocol, the cabinet decision is very disappointing. The energy lobbies have played a big role in this decision."

Position of the United Kingdom

The energy policy of the United Kingdom fully endorses goals for carbon dioxide emissions reduction and has committed to proportionate reduction in national emissions on a phased basis. The United Kingdom is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol.

To date (October 2006), there is no legislative framework in place within the UK to guarantee year-on-year reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouses gases. To date, some 413 Members of Parliament, or around two-thirds of the total, have signed Early Day Motion 178 calling for the introduction of a Climate Change Bill that will address this issue, making a proposed 3% annual cut in carbon dioxide emissions legally binding. Despite a strong lobby from environmental organisations, such as Friends of the Earth's Big Ask Climate Campaign and wide cross-party support, the Bill failed to pass its second reading. However, the Government looks set to include a Climate Change Bill in the Queen's opening speech to Parliament in November, but is expected to ignore intense pressure from its own and opposition parties, and from environmental groups to include the annual 3% reduction commitment in the Bill.

The UK currently appears on course to meet its Kyoto target for the basket of greenhouse gases, assuming the Government is able to curb rising carbon dioxide emissions between now (2006) and the period 2008-2012. However, annual net carbon dioxide emission levels in the UK have actually risen by around 2 per cent since Tony Blair's Labour Party came to power in 1997 . Furthermore, it now seems highly unlikely that the Government will be able to honour its manifesto pledge to cut carbon dioxide emissions by 20 per cent from 1990 levels by the year 2010, unless a Climate Change Act is passed in 2006-7 and the Government takes immediate and drastic action to curb emissions over the next few years.

Position of India

India signed and ratified the Protocol in August, 2002. Since India is exempted from the framework of the treaty, it is expected to gain from the protocol in terms of transfer of technology and related foreign investments. At the G-8 meeting in June 2005, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh pointed out that the per-capita emission rates of the developing countries are a tiny fraction of those in the developed world. Following the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, India maintains that the major responsibility of curbing emission rests with the developed countries, which have accumulated emissions over a long period of time.

Position of Russia

Vladimir Putin approved the treaty on November 4, 2004 and Russia officially notified the United Nations of its ratification on November 18, 2004. The issue of Russian ratification was particularly closely watched in the international community, as the accord was brought into force 90 days after Russian ratification ( February 16, 2005).

President Putin had earlier decided in favour of the protocol in September 2004, along with the Russian cabinet, against the opinion of the Russian Academy of Sciences, of the Ministry for Industry and Energy and of the then president's economic advisor, Andrey Illarionov, and in exchange to EU's support for the Russia's admission in the WTO. As anticipated after this, ratification by the lower ( 22 October 2004) and upper house of parliament did not encounter any obstacles.

The Kyoto Protocol limits emissions to a percentage increase or decrease from their 1990 levels. Since 1990 the economies of most countries in the former Soviet Union have collapsed, as have their greenhouse gas emissions. Because of this, Russia should have no problem meeting its commitments under Kyoto, as its current emission levels are substantially below its targets.

It is debatable whether Russia will benefit from selling emissions credits to other countries in the Kyoto Protocol.

Position of the United States

The United States (U.S.), although a signatory to the protocol, has neither ratified nor withdrawn from the protocol. The signature alone is symbolic, as the protocol is non-binding over the United States unless ratified. The United States is as of 2005 the largest single emitter of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels.

On July 25, 1997, before the Kyoto Protocol was finalized (although it had been fully negotiated, and a penultimate draft was finished), the U.S. Senate unanimously passed by a 95–0 vote the Byrd-Hagel Resolution (S. Res. 98), which stated the sense of the Senate was that the United States should not be a signatory to any protocol that did not include binding targets and timetables for developing as well as industrialized nations or "would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States". On November 12, 1998, Vice President Al Gore symbolically signed the protocol. Both Gore and Senator Joseph Lieberman indicated that the protocol would not be acted upon in the Senate until there was participation by the developing nations. The Clinton Administration never submitted the protocol to the Senate for ratification.

The Clinton Administration released an economic analysis in July 1998, prepared by the Council of Economic Advisors, which concluded that with emissions trading among the Annex B/Annex I countries, and participation of key developing countries in the " Clean Development Mechanism" — which grants the latter business-as-usual emissions rates through 2012 — the costs of implementing the Kyoto Protocol could be reduced as much as 60% from many estimates. Other economic analyses, however, prepared by the Congressional Budget Office and the Department of Energy Energy Information Administration (EIA), and others, demonstrated a potentially large decline in GDP from implementing the Protocol.

The current President, George W. Bush, has indicated that he does not intend to submit the treaty for ratification, not because he does not support the Kyoto principles, but because of the exemption granted to China (the world's second largest emitter of carbon dioxide ). Bush also opposes the treaty because of the strain he believes the treaty would put on the economy; he emphasizes the uncertainties which he asserts are present in the climate change issue. Furthermore, the U.S. is concerned with broader exemptions of the treaty. For example, the U.S. does not support the split between Annex I countries and others. Bush said of the treaty:

This is a challenge that requires a 100% effort; ours, and the rest of the world's. The world's second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases is the People's Republic of China. Yet, China was entirely exempted from the requirements of the Kyoto Protocol. India and Germany are among the top emitters. Yet, India was also exempt from Kyoto … America's unwillingness to embrace a flawed treaty should not be read by our friends and allies as any abdication of responsibility. To the contrary, my administration is committed to a leadership role on the issue of climate change … Our approach must be consistent with the long-term goal of stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere."

Despite its refusal to submit the protocol to Congress for ratification, the Bush Administration has taken some actions towards mitigation of climate change. In June 2002, the American Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released the "Climate Action Report 2002". Some observers have interpreted this report as being supportive of the protocol, although the report itself does not explicitly endorse the protocol. At the G-8 meeting in June 2005 administration officials expressed a desire for "practical commitments industrialized countries can meet without damaging their economies". According to those same officials, the United States is on track to fulfill its pledge to reduce its carbon intensity 18% by 2012. The United States has signed the Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate, a pact that allows those countries to set their goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions individually, but with no enforcement mechanism. Supporters of the pact see it as complementing the Kyoto Protocol while being more flexible, but critics have said the pact will be ineffective without any enforcement measures.

The U.S. government has attempted to suppress reports by experts that find dangerous effects of global warming. A government official blocked release of a fact sheet by a panel of seven scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that finds that global warming is contributing to the frequency and strength of hurricanes.

The Administration's position is not uniformly accepted in the U.S. For example, Paul Krugman notes that the target 18% reduction in carbon intensity is still actually an increase in overall emissions. The White House has also come under criticism for downplaying reports that link human activity and greenhouse gas emissions to climate change and that a White House official and former oil industry advocate, Philip Cooney, watered down descriptions of climate research that had already been approved by government scientists, charges the White House denies. Critics point to the administration's close ties to the oil and gas industries. In June 2005, State Department papers showed the administration thanking Exxon executives for the company's "active involvement" in helping to determine climate change policy, including the U.S. stance on Kyoto. Input from the business lobby group Global Climate Coalition was also a factor.

Furthermore, supporters of Kyoto have undertaken some actions outside the auspices of the Bush Administration. In 2002, Congressional researchers who examined the legal status of the Protocol advised that signature of the UNFCCC imposes an obligation to refrain from undermining the Protocol's object and purpose, and that while the President probably cannot implement the Protocol alone, Congress can create compatible laws on its own initiative. Nine north-eastern states and 194 mayors from US towns and cities, have pledged to adopt Kyoto-style legal limits on greenhouse gas emissions. On August 31 2006, the California Legislature reached an agreement with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to reduce the state's greenhouse-gas emissions, which rank at 12th-largest in the world, by 25 percent by the year 2020. This resulted in the Global Warming Solutions Act which effectively puts California in line with the Kyoto initiative.

Support for Kyoto

Advocates of the Kyoto Protocol claim that reducing these emissions is crucially important; carbon dioxide, they believe, is causing the earth's atmosphere to heat up. This is supported by attribution analysis.

The governments of all of the countries whose parliaments have ratified the Protocol are supporting it. Most prominent among advocates of Kyoto have been the European Union and many environmentalist organizations. The United Nations and some individual nations' scientific advisory bodies (including the G8 national science academies) have also issued reports favoring the Kyoto Protocol.

An international day of action was planned for 3 December 2005, to coincide with the Meeting of the Parties in Montreal. The planned demonstrations were endorsed by the Assembly of Movements of the World Social Forum.

A group of major Canadian corporations also called for urgent action regarding climate change, and have suggested that Kyoto is only a first step.

In Australia, there is significant support for the protocol, with over 22,500 signatures on the Greenpeace petitions.

On 3 January 2006, after the Montreal accords a group of people assembled a petition with the goal to reach 50 million signatures supporting Kyoto Protocol and its goal by January 2008 - the starting date set by the Kyoto Protocol to show average 5% reduction in emissions. This petition was set out to give civil support and ratification to the international fight against Global Warming on a base of world wide active cooperation. Many US and Australian citizens are signing the petition and thus criticise their leaders' choices on this matter.

Grassroots support in the US

In the US, there is at least one student group Kyoto Now! which aims to use student interest to support pressure towards reducing emissions as targeted by the Kyoto Protocol compliance.

As of June 20, 2006, seven Northeastern US states are involved in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), which is a state level emissions capping and trading program. It is believed that the state-level program will indirectly apply pressure on the federal government by demonstrating that reductions can be achieved without being a signatory of the Kyoto Protocol.

- Participating states: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware.

- Observer states and regions: Pennsylvania, Maryland, District of Columbia, Eastern Canadian Provinces.

- Formerly participating states that have dropped out: Massachusetts, Rhode Island

As of October 19, 2006, 320 US cities in 46 states, representing more than 50 million Americans support Kyoto after Mayor Greg Nickels of Seattle started a nationwide effort to get cities to agree to the protocol.

- Large participating cities: Seattle, New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, Denver, New Orleans, Minneapolis, Austin, Portland, Providence, Tacoma, San Jose, Salt Lake City, Little Rock, West Palm Beach, Annapolis, Madison, Wisconsin

- Full list of cities and mayors:

Opposition to Kyoto

The two major countries currently opposed to the treaty are the United States and Australia. Some public policy experts who are skeptical of global warming see Kyoto as a scheme to either slow the growth of the world's industrial democracies or to transfer wealth to the third world in what they claim is a global socialism initiative. Others argue the protocol does not go far enough to curb greenhouse emissions (Niue, The Cook Islands, and Nauru added notes to this effect when signing the protocol).

Many environmental economists have been critical of the Kyoto Protocol. Many see the costs of the Kyoto Protocol as outweighing the benefits, some believing the standards which Kyoto sets to be too optimistic, others seeing a highly inequitable and inefficient agreement which would do little to curb greenhouse gas emissions. It should be noted, however, that this opposition is not unanimous, and that the inclusion of emissions trading has led some environmental economists to embrace the treaty.

Further, there is a controversy to use 1990 as a base year, or not to use a per capita emission as a basis. Countries had different achievements in energy efficiency in 1990. For example, the former Soviet Union and eastern European countries did little to tackle the problem and their energy efficiency was at their worst level in 1990 as the year was just before their communist regimes fell, on the other hand Japan as a big importer of natural resources had to improve their efficiency after the 1973 oil crisis and their emission level in 1990 was better than most developed countries. However, such efforts were set aside, and the inactivity of the former Soviet Union was overlooked and could even generate big income due to the emission trade. There is an argument that the use of per capita emission as a basis in the following Kyoto-type treaties can reduce the inequality feelings among the developed and developing countries alike as it can reveal inactivities and responsibilities among countries.

In Australia, there is a strong and vocal anti-Kyoto lobby, with over 20,000 counter signatures presented to the government.

Cost-benefit analysis

Economists have been trying to analyse the overall net benefit of Kyoto Protocol through cost-benefit analysis. Just as in the case of climatology, there is disagreement due to large uncertainties in economic variables. Still, the estimates so far generally indicate either that observing the Kyoto Protocol is more expensive than not observing the Kyoto Protocol or that the Kyoto Protocol has a marginal net benefit which exceeds the cost of simply adjusting to global warming. A study in Naturefound that "accounting only for local external costs, together with production costs, to identify energy strategies, compliance with the Kyoto Protocol would imply lower, not higher, overall costs."

The recent Copenhagen consensus project found that the Kyoto Protocol would slow down the process of global warming, but have a superficial overall benefit. Defenders of the Kyoto Protocol argue, however, that while the initial greenhouse gas cuts may have little effect, they set the political precedent for bigger (and more effective) cuts in the future. They also advocate commitment to the precautionary principle. Critics point out that additional higher curb on carbon emission is likely to cause significantly higher increase in cost, making such defence moot. Moreover, the precautionary principle could apply to any political, social, economic or environmental consequence, which might have equally devastating effect in terms of poverty and environment, making the precautionary argument irrelevant. The Stern Review (a UK government sponsored report into the economic impacts of climate change) concluded that one percent of global GDP is required to be invested in order to mitigate the effects of climate change, and that failure to do so could risk a recession worth up to twenty percent of global GDP.

Discount rates

One problem in attempting to measure the "absolute" costs and benefits of different policies to global warming is choosing a proper discount rate. Over a long time horizon such as that in which benefits accrue under Kyoto, small changes in the discount rate create very large discrepancies between net benefits in various studies. However, this difficulty is generally not applicable to "relative" comparison of alternative policies under a long time horizon. This is because changes in discount rate tend to equally adjust the net cost/benefit of different policies unless there are significant discrepancies of cost and benefit over time horizon.

While it has been difficult to arrive at a scenario under which the net benefits of Kyoto are positive using traditional discounting methods such as the Shadow Price of Capital approach, there is an argument that a much lower discount rate should be utilized; that high rates are biased toward the current generation. This may appear to be a philosophical value judgement, outside the realm of economics, but it could be equally argued that the study of the allocation of resources does include how those resources are allocated over time.

Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate

The Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate is an agreement between six Asia-Pacific nations: Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. It was introduced at the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), regional forum on July 28, 2005. The pact allows those countries to set their goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions individually, but with no enforcement mechanism. Supporters of the pact see it as complementing the Kyoto Protocol whilst being more flexible while critics have said the pact will be ineffective without any enforcement measures and ultimately aims to void the negotiations leading to the Protocol called to replace the current Kyoto Protocol (negotiations started in Montreal in December 2005).