Eastern Orthodox Church

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Religious movements, traditions and organizations

|

|||||||

The Eastern Orthodox Church is a religious organization which sees itself as the continuation of the original Christian body, founded by Jesus and his Twelve Apostles. The present church links its hierarchy historically directly back to the apostles through the process described in the Bible as the laying on of hands (Acts 8:17, 2 Timothy 1:6, Hebrews 6:2) otherwise referred to as Apostolic Succession. The church keeps strict records of these Episcopal pedigrees for each of its bishops (example: see List of Ecumenical Patriarchs of Constantinople). It also claims to have preserved the sacred traditions given to the members of the Church through letter and word of mouth. In comparing its current organization to the early church it believes the only changes have been in administrative complexity and in the “clarification” of its doctrines. Its theological beliefs (once defined) have remained the same. These beliefs have been adopted by numerous peoples and nations who have each added their particular flavor to church practices (without changing its beliefs), while at the same time remaining unified worldwide. Despite the various labels applied to it, it officially calls itself the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. It currently encompasses national jurisdictions such as the Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox and other Churches (see Eastern Orthodox Church organization). It is sometimes referred to as the Orthodox Catholic Church to emphasize its counter claim to The Roman Catholic Church as being the Catholic Church, but is more often known simply as Orthodoxy or the Orthodox Church.

On the basis of the numbers of adherents, Eastern Orthodoxy is the second largest Christian communion in the world after the Roman Catholic Church, and the third largest grouping overall after Protestantism. There are approximately 220 million Eastern Orthodox Christians worldwide. Eastern Orthodoxy is the largest single religious faith in Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Ukraine, but there are also large Orthodox communities in Africa, Asia, Australia, North America, and South America.

Terminology

The term orthodox is Greek and means Correct Worship. It is a title the Church adopted during the Great Schism to distinguish itself from the Roman Catholics. The term "Orthodox", without reference to geographical location, is conventionally used by all members of the church to highlight what they see as their full adherence to the pronouncements of the seven ecumenical councils and their absolute reluctance to break with holy tradition.

Although geographical or ethnic designators such as "Eastern", "Greek" or "Russian" are in common use, the Orthodox Church sees itself as a single unified body, encompassing both the living and the dead. It therefore properly uses the Greek term “Catholic” to describe itself.

In the remainder of this article, for convenience of reference, the expressions "Orthodox" and "the Church" refer to "Eastern Orthodox" unless the context indicates otherwise.

Organization

The basic administrative structure of the church is simple. Parishes, ideally, are small with their members seeking spiritual guidance from monastics and the clergy. Parish priests usually know their flock quite well, having intimate knowledge of their problems through the mystery of confession. Priests teach and administer to their flock and perform the various services of the church in place of bishops. Bishops likewise advise and govern the priests, and through them, their flock. A single bishop may have any number of priests under his charge. While bishops do not interfere in each others territories they are usually organized into democratic councils (Synods) in order to administer their jurisdiction. Abbots and abbesses have similar control over their monasteries. There is no single leader in the church. No pope. All bishops are equal. The Patriarch of Constantinople has the distinction of acting as “president” of any ecumenical council, should one be called (the last one was in 787AD), for this he is called “First Among Equals”.

Because of this structure the spiritually undivided church can be administratively divided into various autocephalous (that is, self-governing) organizations with their own episcopal hierarchies, hence the terms Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, etc. These groups, in general, recognize each other as being within the body of the Church (i.e. canonical).

There are a number of churches that are not considered to be part of this group, who have, for one reason or another been excised from the church and should not be confused with its members.

- The Oriental Orthodox represent a branch of the original church that rejected the pronouncements of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD

- The Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church separated in 1054 AD over issues that included the Pope being the Supreme authority in the church and the addition to the creed of the “Filioque” clause.

- The Byzantine Catholics and/or the Eastern Rite Catholics, who recognize the Pope.

Beliefs

The Trinity

Orthodox Christians believe in a single God who is both three and one (triune): Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Holy Trinity is three unconfused, distinct, divine persons ( hypostases), with no overlap or modality among them, who share one divine essence (ousia)—uncreated, immaterial and eternal. In discussing God's relationship to his creation a distinction is made between God's eternal essence and uncreated energies.

The Father is the eternal source of the Godhead, from whom the Son is begotten eternally and also from whom the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally. Orthodox doctrine regarding the Holy Trinity is summarized in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed.

Sin, salvation and the Incarnation

Adam and Eve sinned when they disobeyed God in the Garden of Eden, thus introducing into mankind the disease of sin. This event, the Fall of Man, altered the dynamic state of humanity's existence, making him prone to sin, which is an ontological separation from God. Although it is now possible for human beings to choose not to sin, their tendency is toward it. The consequence of the Fall is the introduction of death to humanity; it is death--and the fear of it--which is seen to be the progenitor of man's sins. All mankind is thus in need of salvation, which is the process of restoring man to the pure state in which he was created and growing him even beyond that toward perfection. This process, termed theosis ( Greek, "deification" or "divinization"), is eternal and is the continual deepening of communion between God and man, a unification without fusion of the human person with the divine persons.

The second person of the Trinity, the Son of God, thus became genuine man in order to accomplish salvation for humanity, which is incapable of doing so on its own. Eastern Orthodox theology teaches that when the Son of God became the man Jesus Christ, he took on human nature while keeping his divine nature. He is thus one person (hypostasis) with two natures. Orthodox soteriology is therefore aimed at the bringing of man by grace to become what Christ is by nature, that is, being holy. This process neither sacrifices monotheism nor the eternal distinction between the created and the uncreated, because it is eternal and there is no final arrival point.

Progress toward salvation is accomplished in the earthly life only by God's grace, with which man must freely cooperate. The free cooperation of man includes prayer, asceticism, participation in the sacraments, following the commandments of Christ, and above all, repentance of sin. Salvation is thus for the whole human person, involving both the body and the soul.

The Resurrection

The Resurrection of Christ is the central event in the liturgical year of the Orthodox Church and is understood in literal terms as a real historical event. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, was crucified and died, descended into Hell, rescued all the souls held there through man's original sin; and then, because Hell could not restrain the infinite God, rose from the dead, thus saving all mankind. Through these events, he released mankind from the bonds of Hell and then came back to the living as man and God. That each individual human may partake of this immortality, which would have been impossible without the Resurrection, is the main promise held out by God in his New Testament with mankind, according to Orthodox Christian tradition.

Every holy day of the Orthodox liturgical year relates to the Resurrection directly or indirectly. Every Sunday of the year is dedicated to celebrating the Resurrection; Orthodox believers refrain from kneeling or prostrating on Sundays in observance thereof. In the liturgical commemorations of the Passion of Christ during Holy Week there are frequent allusions to the ultimate victory at its completion.

The Bible, Holy Tradition, and the patristic consensus

The Orthodox Church considers itself to be the original Church founded by Christ and His apostles. The faith taught by Jesus to the apostles, given life by the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and passed down to future generations uncorrupted, is known as Holy Tradition. The primary witness to Holy Tradition is the Bible, texts written or approved by the apostles to record revealed truth and the early history of the Church. Because of the Bible's apostolic origin, it is regarded as central to the life of the Church.

The Bible is always interpreted within the context of Holy Tradition, which gave birth to it and canonized it. Orthodox Christians maintain that belief in a doctrine of sola scriptura would be to take the Bible out of the world in which it arose. Orthodox Christians therefore believe that the only way to understand the Bible correctly is within the Orthodox Church.

Other witnesses to Holy Tradition include the liturgy of the Church, its iconography, the rulings of the Ecumenical councils, and the writings of the Church Fathers. From the consensus of the Fathers (consensus patrum) one may enter more deeply and understand more fully the Church's life. Individual Fathers are not looked upon as infallible, but rather the whole consensus of them together will give one a proper understanding of the Bible and Christian doctrine.

The Theotokos and the saints

The saints are regarded as those who have reliably finished the course of their lives in the path of theosis. Those that are known to the Church are glorified ( canonized) by incorporating their lives into the Church's liturgical life, a recognition of Christ in them. They are venerated (shown great respect and love) but not worshiped, for worship is due to God alone. In showing the saints this love and requesting their prayers, it is believed by the Orthodox that they thus assist in the process of salvation for others.

Newly baptized Orthodox Christians are usually given the name of a saint, both to place the new Christian in the community of the Church and also to ask for that saint to pray especially for that person's salvation.

Preeminent among the saints is the Virgin Mary, the Theotokos ("birthgiver to God"). The Theotokos was chosen by God and freely cooperated in that choice to be the mother of Jesus Christ, the God-man. She did not give birth to his divinity, but rather to one person whose two natures were united at his miraculous virgin conception. She is thus called Theotokos as an affirmation of the divinity of the one to whom she gave birth. Because of her unique place in salvation history, she is honored above all other saints and especially venerated for the great work that God accomplished through her.

Because of the holiness of the lives of the saints, their bodies and physical items connected with them are regarded by the Church as also holy. Many miracles have been reported throughout history connected with the saints' relics, often including healing from disease and injury. The veneration and miraculous nature of relics continues from Biblical times.

Eschatology

The doctrine of the Eastern Orthodox Church is amillennialist. Amillennialism teaches that the Kingdom of God will not be physically established on earth throughout the "millennium", but rather

- that Christ is presently reigning from heaven, seated at the right hand of God the Father,

- that Christ also is and will remain with the Christian church until the end of the world, as he promised at the Ascension,

- that at Pentecost, the millennium began, as is shown by Peter using the prophecies of Joel, about the coming of the kingdom, to explain what was happening,

- and that, therefore the Christian church and its spread of the good news is Christ's kingdom.

However, at least during the first four centuries, millennialism was normative in both East and West. Tertullian, Commodian, Lactantius, Methodius, and Apollinaris of Laodicea all advocated premillennial doctrine. (PDF file) In addition, according to religious scholar Rev. and Dr. Francis Nigel Lee the following is true, "Justin's 'Occasional Chiliasm' sui generis which was strongly anti-pretribulationistic was followed possibly by Pothinus in A.D. 175 and more probably (around 185) by Irenaeus -- although Justin Martyr, discussing his own premillennial beliefs in his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Chapter 110, observed that they were not necessary to Christians:

- I admitted to you formerly, that I and many others are of this opinion, and [believe] that such will take place, as you assuredly are aware; but, on the other hand, I signified to you that many who belong to the pure and pious faith, and are true Christians, think otherwise.

Around 220, there were some similar influences on Tertullian though only with very important and extremely optimistic (if not perhaps even postmillennial modifications and implications). On the other hand, 'Christian Chiliastic' ideas were indeed advocated in 240 by Commodian; in 250 by the Egyptian Bishop Nepos in his Refutation of Allegorists; in 260 by the almost unknown Coracion; and in 310 by Lactantius.

Melito of Sardis is frequently listed as a second century proponent of premillennialism. . The support usually given for the supposition is that Jerome [Comm. on Ezek. 36 ] and Gennadius [De Dogm. Eccl., Ch. 52] both affirm that he was a decided millenarian.”. However, such prominent theologians as Clement of Alexandria, Augustine of Hippo, Eusebius of Caesarea, Origen and others, taught against pre-millennial views. Chiliasm was condemned as a heresy in the 4th century by the Church, which included the phrase whose Kingdom shall have no end in the Nicene Creed in order to rule out the idea of a Kingdom of God which would last for only 1000 literal years. Despite some writers' belief in millennialism, it was a decided minority view, as expressed in the nearly universal condemnation of the doctrine.

Traditions

Art and architecture

Church buildings

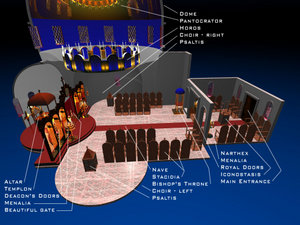

The church building has many symbolic meanings; perhaps the oldest and most prominent is the concept that the Church is the Ark (as in Noah's) in which the world is saved from the flood of temptations. Because of this, most Orthodox Churches are rectangular in design. Another popular shape, especially for churches with large choirs is cruciform or cross-shaped. Architectural patterns may vary in shape and complexity, with chapels sometimes added around the main church, or triple altars (Liturgy may only be performed once a day on any particular altar), but in general, the symbolic layout of the church remains the same.

The Church building is divided into three main parts: the narthex (entrance hall), the nave and the sanctuary (also called the altar or holy place).

Narthex: The narthex is the connection between the Church and the outside world and for this reason catechumens (pre-baptized Orthodox) and non-Orthodox stand here (note: the tradition of allowing only confirmed Orthodox into the nave of the church has for the most part fallen into disuse). In monastic churches it is usual for the lay people visiting the monastery to stand in the narthex while the monks or nuns stand in the nave. Separating the narthex from the nave are the Royal Doors (from the time of the Byzantine Empire, when the emperor would enter the main body of Hagia Sophia, the Church of Holy Wisdom, through these doors and proceed up to the altar to partake of the Eucharist). On either side of this portal are large brass candlestands called menalia which represent the pillars of fire which went before the Hebrews into the promised land.

Nave: The nave is the main body of the church where the people stand during the services. In most Orthodox churches there are no pews but rather stacidia (like a high-armed chair with foldup seat—its arm rests are high enough to be used for support while standing; these are usually found along the walls. Traditionally there is no sitting during services with the only exceptions being during the reading of the Psalms, and the priest's sermon. The people stand before God. However because of the influence of Catholic and Protestant practices in western countries it is not uncommon to find pews and kneelers in more modern church structures.

The walls are normally covered from floor to ceiling with icons or wall paintings of saints, their lives, and stories from the Bible. Because the church building is a direct extension of its Jewish roots where men and women stand separately, the Orthodox Church continues this practice, with men standing on the right and women on the left. Because of this arrangement it is emphasized that we are all equal before God (equal distance from the altar), and that the man is not superior to the woman. In many modern churches this traditional practice has been altered and families stand together.

Above the nave in the dome of the church is the icon of Christ the Almighty (Pantokratoros, "Ruler of All"). Directly hanging below the dome (In more traditional churches) is usually a kind of circular chandelier with depictions of the saints and apostles, called the horos.

Iconostasis: Traditionally called the templon, it is a screen or wall between the nave and the sanctuary, which is covered with icons. There will normally be three doors, one in the middle and one on either side. The central one is traditionally called the Beautiful Gate and is only used by the clergy. There are times when this gate is closed during the service and a curtain is drawn. The doors on either side are called the Deacons' Doors or Angel Doors as they often have depicted on them the Archangels Michael and Gabriel. These doors are used by deacons and servers to enter the sanctuary. Typically, to the left of the Beautiful Gate (as seen from the altar) is the icon of Christ, then the icon of St John the Baptist; to the right the icon of the Theotokos, always shown holding Christ; and then the icon of the saint to whom the church is dedicated (i.e., the patron). There are often other icons on the iconostasis but these vary from church to church. Above and behind the iconostasis (if the iconostasis does not reach the ceiling) is the Platytera ton Ouranon ("more spacious than the heavens"), the icon of Virgin Mary with Christ blessing all. Oil lamps burn before all the icons.

Sanctuary: The area including the altar table at its centre, behind the iconostasis: it is the "Holy of Holies" of the church. The church, if at all possible, is always aligned with the altar facing East. The priest also faces East when before the holy table (away from the congregation), offering prayers for the people to God and then coming out through the Beautiful Gate to give God's good news (Gospel) to the people. To the left of the altar table will be the Prosthesis table (table of preparation) where the bread and wine are prepared for the Eucharist before the Divine Liturgy begins.

Icons

The term Icon comes from the Greek word eikon, which simply means image. Icons are replete with symbolism meant to convey far more meaning than simply the identity of the person depicted, and it is for this reason that Orthodox iconography has become an exacting science of copying older icons rather than an opportunity for artistic expression. The Orthodox believe that the first icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary were painted by Luke the Evangelist. The personal, idiosyncratic and creative traditions of Western European religious art are largely lacking in Orthodox iconography before the 17th century, when Russian icon painting was strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from both Protestant and Catholic Europe. Greek icon painting also began to take on a strong romantic western influence for a period and the difference between some Orthodox icons and western religious art began to vanish. More recently there has been a strong trend of returning to the more traditional and symbolic representations.

Statues (three dimensional depictions) are almost non-existent within the Orthodox Church. This is partly due to the rejection of the previous pagan Greek age of idol worship and partly because Icons are meant to show the spiritual nature of man, not the sensual earthly body. Icons are not considered by the Orthodox to be objects of worship. Their usage is justified by the following logic: When the immaterial God was all that we had, no material depiction was possible and therefore blasphemous even to contemplate; however, biblical prohibitions against material depictions have been altered by Christ (as God) taking on material form, thus allowing a material depiction. Also, it is not the wood or paint that are venerated but rather the individual shown, just as with a portrait or photograph of a loved one. As Saint Basil famously proclaimed, honour or veneration of the icon always passes to its prototype. Following this reasoning through, our veneration of the glorified human Saint made in God's image, is always a veneration of the divine image, and hence God as foundational prototype.

Large icons can be found adorning the walls of churches and often cover the inside structure completely. Orthodox homes often likewise have icons hanging on the wall, usually together on an eastern facing wall, and in a central location where the family can pray together.

Icons are often illuminated with a candle or oil lamp. (Beeswax for candles and olive oil for lamps are preferred because they are natural and burn cleanly.) Besides the practical purpose of making icons visible in an otherwise dark church, both candles and oil lamps symbolize the Light of the World which is Christ.

Tales of miraculous icons that moved, spoke, cried, bled, or gushed fragrant myrrh are not uncommon, though it has always been considered that the message of such an event was for the immediate faithful involved and therefore does not usually attract crowds. Some miraculous icons whose reputations span long periods of time nevertheless become objects of pilgrimage along with the places where they are kept. As several orthodox theologians and saints have explored in the past, the icons miraculous nature is found not in the material, but in the glory of the saint who is depicted in the icon. The icon is a window, in the words of St Paul Florensky, that literally participates in the glory of what it represents! This is why several icons bleed myrrh, which is a physical manifestation of the uncreated holy spirit.

Some of the most venerated Russian Orthodox icons are treated in separate articles.

See also Category:Eastern Orthodox icons.

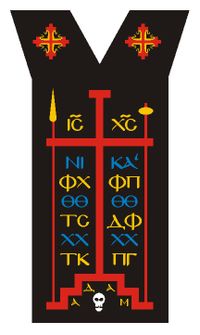

The Cross: The Byzantine (sometimes Russian) style cross (seen right) is usually shown with a small top crossbar representing the sign that Pontius Pilate nailed above Christ's head, however, instead of the Latin acronym INRI (Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, meaning "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews") the Greek INBI or its Slavonic equivalent is used. It is not uncommon, however, for this to be replaced by the phrase "The King of Glory" in order to answer Pilate's mocking statement with Christ's affirmation, "My Kingdom is not of this world". There is also on many Orthodox depictions of the cross a bottom slanting bar. This appears for a number of reasons. First of all, there is enough evidence to show that there was a small wooden platform for the crucified to stand on in order to support his weight; in Christ's case his feet were nailed side by side to this platform with one nail each in order to prolong the torture of the cross. Evidence for this idea comes mainly from two sources, biblical (that in order to cause the victim to die faster their legs were broken so they could not support their weight and would strangle) and tradition (all early depictions of the crucifixion show this arrangement, not the later with feet on top with single nail). It has also been pointed out that the nailed hands of a body crucified in the manner often shown in modern secular art would not support the weight and would tear through, a platform for the feet would relieve this problem. The bottom bar is slanted for two reasons, to represent the very real agony which Christ experienced on the cross (a refutation of Docetism) and to signify that the thief on Christ's right chose the right path while the thief on the left did not.

In Unicode, this cross is U+2626 (☦).

The Services

The services of the church are properly conducted each day following a rigid, but constantly changing annual schedule (i.e. Parts of the service remain the same while others change depending on the day of the year). Services are conducted in the church by the clergy. Services cannot properly be conducted by a single person, but must have at least one other person present (i.e. a Priest and a Chanter). Usually, all of the services are conducted on a daily basis only in monasteries while parish churches might only do the services on the weekend. The services can be conducted at their traditional times of the day, or on special feast days served all together (Agripnia) from late at night till early the next morning. Traditionally the services follow the following schedule:

Vespers – (Greek Hesperinos) Sundown, the beginning of the liturgical day.

Compline (Greek Apodipnon, lit. "After-supper") – After the evening meal prior to bedtime.

Matins (Greek Orthros) – First service of the morning. Usually starts before sunrise.

Hours – First, Third, Sixth, and Ninth – Sung either at their appropriate times, or in aggregate at other customary times of convenience. If the latter, The First Hour is sung immediately following Orthros, the Third and Sixth prior to the Divine Liturgy, and the Ninth prior to Vespers.

These services are conceived of as sanctifying the times during which they are celebrated. They consist to a large degree of readings from the Psalter with introductory prayers, troparia, and other prayers surrounding them. The Psalms are so arranged that when all the services are celebrated the entire Psalter is read through in their course once a week, and twice a week during Great Lent when they are celebrated in an extended form.

The Divine Liturgy is the celebration of the Eucharist. Although it usually stands between the 6th and 9th hours, it is considered to occur outside the normal time of the world and is not a sanctification of it. It is also common, on special feast days of the church to celebrate all the services consecutively and to do this from late in the evening on the eve of the feast to early in the morning on the day of the feast itself. This variation is called Agripnia and can last many hours. Because of its festal nature it is usually followed by a breakfast feast shared together by the congregation. Although it may be celebrated on most days, there has never been a tradition of its daily celebration in parish churches.

Liturgies may not be celebrated Monday through Friday during the penetential season of Great Lent due to their festive character. Since intensified prayer and more frequent reception of communion is nevertheless considered particularly beneficial at that time, the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts is often celebrated on Wednesdays and Fridays of that period. This is a solemn Vespers combined with the distribution of Eucharistic elements consecrated and reserved from the previous Sunday.

Chanting

Orthodox services are sung nearly in their entirety. Services consist in part of a dialog between the clergy and the people (often represented by the choir or the Psaltis (Cantor). In each case the text is sung or chanted following a prescribed musical form. Almost nothing is read in a normal speaking voice with the exception of the homily if one is given. The church has developed eight Modes or Tones, (see Octoechos) within which a chant may be set, depending on the time of year, feast days, or other considerations of the Typikon. There are numerous versions and styles that are traditional and acceptable and these vary a great deal between cultures. It is common, especially in the United States, for a choir to learn many different styles and to mix them, singing one response in Greek, then English, then Russian, etc.

Incense

As part of the legacy handed down from its Jewish roots incense is used during all services in the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is burned as an offering of worship to God even as it was done in the Jewish temple. Traditionally, the base of the incense used is the resin of Boswellia thurifera, also known as frankincense, but the resin of fir trees has been used as well. It is usually mixed with various floral essential oils giving it a sweet smell. Incense represents the sweetness of the prayers of the saints rising up to God (Psalm 141:2, Revelation 5:8, Revelation 8:4). The incense is burned in an ornate golden censer that hangs at the end of Three chains representing the Trinity. In the Greek tradition there are 12 bells hung along these chains representing the 12 apostles; the Slavic churches usually do not have bells. The censer is used (swung back and forth) by the priest/deacon to venerate all four sides of the altar, the holy gifts, the clergy, the icons, the congregation, and the church structure itself.

The Mysteries

The Mysteries within the Orthodox Church, unlike the Roman Catholic Sacraments, are more numerous (than 7) and less analyzed. An Orthodox definition of mystery might be any action in which a person connects to God. Communion is the most prominent (the direct physical union with Christ’s Body and Blood), followed by baptism, confession, marriage, and so forth; but the term also properly applies to act as simple as lighting a candle, burning incense, and praying or asking God to bless one's food.

Baptism

Baptism is the mystery which transforms the old sinful man into the new, pure man. The old life, the sins, any mistakes made are gone and a clean slate is given. Through baptism one is united to the Body of Christ by becoming a member of the Orthodox Church. During the service water is blessed. The catechumen is fully immersed in the water three times in the name of the Holy Trinity. This is considered to be a death of the "old man" by participation in the crucifixion and burial of Christ, and a rebirth into new life in Christ by participation in his resurrection. Usually a new name is given, which becomes the person's name. Because it is believed this is a new person and all previous commitments are void; if the person was formerly married, they must now be married again.

Children of Orthodox families are normally baptized shortly after birth. Traditionally, converts from other religions, even other Christians must be properly baptised into the Orthodox Church. However, local practices vary and are largely dependant on the bishop. If the bishop chooses to exercise "economia", such converts may be received by baptism, chrismation, or just by confession of the Orthodox faith (this practice is usually allowed only if the person is too ill to be properly baptized).

Properly, the mystery of baptism is administered by bishops and priests; however, in emergencies any Orthodox Christian can baptize.

The service of baptism used in Orthodox churches has remained largely unchanged for over 1500 years. This fact is witnessed to by St. Cyril of Jerusalem (d. 386), who, in his Discourse on the Sacrament of Baptism, describes the service in much the same way as is currently in use.

Chrismation

Chrismation (sometimes called confirmation) is the mystery by which a person, who has been baptized is granted the gift of the Holy Spirit through anointing with Holy Chrism. It is normally given immediately after baptism as part of the same service, but is also used to receive lapsed members of the Orthodox Church. As baptism is a person's participation in the death and resurrection of Christ, so chrismation is a person's participation in the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

A baptized and chrismated Orthodox Christian is a full member of the Church, and may receive the Eucharist regardless of age.

Chrism may be blessed by any bishop, but this is usually done only by the chief hierarch of an autocephalous church during Holy Week. (Some autocephalous churches get their chrism from others.) Anointing with it substitutes for the laying-on of hands described in the New Testament.

Fasting

Fasting is a very important practice in the Orthodox Church. Fasting is never seen as a way to earn the believer "points" or the right to salvation; it is instead an exercise in self-denial and Christian obedience that serves to rid the believer of his or her passions (what most modern people would call "addictions"). These often low-intensity and hard-to-detect addictions to food, television or other entertainments, sex, or any kind of self-absorbed pleasure-seeking are seen as some of the most significant obstacles for man seeking closeness to God. Through struggling with fasting the believer comes face to face with the reality of his condition — the starting point for genuine repentance according to the Eastern Orthodox tradition.

Fasting is also never looked on as a hardship or punishment but rather as a great privilege and joy, although it can be very difficult. Those who for medical reasons (diabetes, for example) cannot fast, often see themselves as missing a great spiritual opportunity. Fasting typically involves differing levels of abstinence depending on the day or season and ranges from a complete fast from all food and drink to abstinence from all animal products (meat, dairy, eggs, etc.), olive oil, and wine.

Although the traditional proscription is against olive oil, it is often interpreted as excluding all vegetable oils.

Shellfish is not included in the proscription against meat; accordingly, shellfish is permitted during fasts. (So-called " imitation crabmeat" is not Lenten fare as it is made not made from shellfish but, rather from fish–generally pollock.) Although shellfish is permitted, fasting Orthodox Christians would also need to take into account the overarching principles of denial and moderation; thus, feasts of lobster and crab (like feasts on other luxurious Lenten foods) during fasts could still be contrary to the spirit of fasting.

Vegetable oils are permitted on certain days and weeks of the fast as is wine. Thus, most fasting guidelines resemble a vegan diet with all cooking done simply with water but no oil. In addition to restrictions on food, it is generally understood that married couples abstain from sexual relations during a fast (see 1 Corinthians 7:5) and it is often recommended that entertainments or amusements be eliminated altogether during the stricter periods of fasting.

The time and type of fast is generally uniform for all Orthodox Christians; the times of fasting are part of the ecclesiastical calendar. There are four major fasting periods during the year. They are:

- The Nativity Fast (Advent or Winter Lent) which is the 40 days preceding the Nativity of Christ ( Christmas).

- Great Lent which consists of the 6 weeks (40 Days) preceding Palm Sunday, and Great Week (Holy Week) which precedes Pascha ( Easter).

- The Apostles' Fast which varies in length from 2 to 6 weeks on the Old Calendar. It begins on Monday following the first Sunday after Pentecost and extends to the feast day of Saints Peter and Paul on June 29th. Since the date of Pentecost depends on that of Pascha, and Pascha is determined on the Julian Calendar, this fast can disappear completely under New Calendar observance. This is one of the objections raised to the New Calendar.

- The two-week long Fast preceding the Dormition of the Theotokos (repose of The Virgin Mary).

Orthodox Christians also fast on every Wednesday in commemoration of Christ's betrayal by Judas Iscariot, and on every Friday in commemoration of his crucifixion. Monastics often include Mondays as a fast day in imitation of the Angels who are commemorated on that day in the weekly cycle, since they neither eat nor drink. Orthodox Christians who expect to receive Eucharist on a certain day do not eat or drink at all from midnight of that day until after taking communion; a similar total fast is expected to be kept on Great Friday and Holy Saturday for those who can do so. There are other individual days observed as fasts no matter what day of the week they fall, such as the Beheading of St. John the Baptist on August 29 and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross on September 14.

Strict fasting is canonically forbidden on Saturdays and Sundays due to the festal character of the Sabbath and Resurrectional observances respectively. On those days wine and oil are therefore permitted even if abstention from them would be otherwise called for. Holy Saturday is the only Saturday of the year where a strict fast is kept.

There are four weeks during the year where there is no fasting even on Wednesday and Friday. The weeks following Pascha, Pentecost, and the Nativity are "fast-free" in celebration of the feasts. There is also no fasting for week following the Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee, one of the preparatory Sundays for Great Lent. This is done so that no one can imitate the Pharisee's boast that he fasts for two days out of the week, for that one week at least.

The number of fast days varies each year, but in general the Orthodox Christian can expect to spend over half the year fasting at some level of strictness.

It is considered a greater sin to advertise one's fasting than to not participate in the fast. Fasting is a purely personal communication between the Orthodox and God, and in fact has no place whatsoever in the public life of the Orthodox Church. If one has responsibilities that cannot be fulfilled because of fasting, then it is perfectly permissible not to fast.

Almsgiving

" Almsgiving" refers to any charitable giving of material resources to those in need. Along with prayer and fasting, it is considered a pillar of the personal spiritual practices of the Orthodox Christian tradition. Almsgiving is particularly important during periods of fasting, when the Orthodox believer is expected to share the monetary savings from his or her decreased consumption with those in need. As with fasting, bragging about the amounts given for charity is considered anywhere from extremely rude to sinful.

Holy Communion

The Eucharist is at the centre of Orthodox Christianity. In practice, it is the partaking of bread and wine in the midst of the Divine Liturgy with the rest of the church. The bread and wine are believed to be the genuine Body and Blood of the Christ Jesus. The Eastern Orthodox Church has never described exactly how this occurs, or gone into the detail that the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches have in the West. The doctrine of transubstantiation was formulated after the Great Schism took place, and the Orthodox churches have never formally affirmed or denied it, preferring to state simply that it is a mystery and sacrament.

Communion is given only to baptized, chrismated Orthodox Christians who have prepared by fasting, prayer, and confession (if of the age of reason, see below). The priest will administer the gifts with a spoon directly into the recipient's mouth from the chalice. From baptism young infants and children are carried to the chalice to receive Holy Communion.

It is the opinion of some traditionalists that frequent communion is dangerous spiritually if it reflects a lack of piety in approaching the most significant of the Mysteries, which would be damaging to the soul. However, many spiritual advisors advocate frequent reception as long as it is done in the proper spirit and not casually, with full preparation and discernment. Frequent reception is more common now than in recent centuries.

Repentance

Orthodox Christians who have committed sins but repent of them, and who wish to reconcile themselves to God and renew the purity of their original baptisms, confess their sins to God before their spiritual guide (often a priest, but can be anyone, male or female, who has a blessing to hear confessions), who offers spiritual guidance to assist the individual in overcoming their sin. The penitent then has his or her parish priest read the prayer of repentance over them, asking God for forgiveness and confirming it with a blessing. Sin is not viewed by the Orthodox as a stain on the soul that needs to be wiped out, or a legal transgression that must be set right by a punitive sentence, but rather as a mistake made by the individual with the opportunity for spiritual growth and development. An act of Penance, if the spiritual guide requires it, is never formulaic, but rather is directed toward the individual and their particular problem, as a means of establishing a deeper understanding of the mistake made, and how to affect its cure. Though it sounds harsh, temporary excommunication is fairly common (The Orthodox require a fairly high level of purity in order to commune, therefore certain sins make it necessary for the individual to refrain from communing for a period). Because confession and repentance are required in order to raise the individual to a level capable of communing (though no one is truly worthy), and because full participatory membership is granted to infants, it is not unusual for even small children to confess; though the scope of their culpability is far less than an older child, still their opportunity for spiritual growth remains the same.

Marriage

Orthodox Marriage is seen as an act of God in which he joins two believers (a man and a woman) into one. Procreation is not seen as the only reason for marriage though it is referenced throughout the standard Orthodox Wedding Service. The fact that intimacy between married adults creates a loving bond is paramount, and that union between the two is reflective of an "ultimate union with God." Marriage is understood to be an eternal union of love that, according to some Orthodox theologians (particularly Meyendorff) continues into the heavenly kingdom. These theologians, while holding that marriages aren't formed in the afterlife (Matt 22:30), affirms that the marriage bond sacramentally formed on earth is present in the afterlife, as no sacramental actions can be undone. This belief in the eternality of marriage keeps many Orthodox Christians from getting divorces in traditional Orthodox countries. The Church has never dogmatized on the question of marriage's eternality, however.

The Mystery of Marriage in the Orthodox Church has two distinct parts: The Betrothal and The Crowning. The Betrothal includes: The exchange of the rings, the procession, the declaration of intent and the lighting of candles. Then follows the Crowning, the epistle, the gospel, the Blessing of the Common Cup and the Dance of Isaiah, and then the Removal of the Crowns. Finally there is the Greeting of the Couple.

Unlike the Roman Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church recognizes the reality of divorce (though does not "grant" divorces) and allows divorced men and women to remarry under specific circumstances (infidelity, apostasy, etc.) as judged by a Spiritual Court or bishop. It is regarded as a great tragedy, however, and a second marriage normally requires special permission from a bishop. A second wedding is always performed in the context of repentance on the part of the previously married party, a fact reflected in the ceremony.

A peculiarity of the Orthodox wedding ceremony is that there is no exchange of vows. There is a set expectation of the obligations incumbent on a married couple, and whatever promises they may have privately to each other are their responsibility to keep.

Monasticism

All Orthodox Christians are expected to participate in at least some ascetical works, in response to the commandment of Christ to "come, take up the cross, and follow me." ( Mark 10:21 and elsewhere) They are therefore all called to imitate, in one way or another, Christ himself who denied himself to the extent of literally taking up the cross on the way to his voluntary self-sacrifice. However, laypeople are not expected to live in extreme asceticism since this is close to impossible while undertaking the normal responsibilities of worldly life. Those who wish to do this therefore separate themselves from the world and live as monastics: monks and nuns. As ascetics par excellence, using the allegorical weapons of prayer and fasting in spiritual warfare against their passions, monastics hold a very special and important place in the Church. This kind of life is often seen as incompatible with any kind of worldly activity including that which is normally regarded as virtuous. Social work, schoolteaching, and other such work is therefore usually left to laypeople.

There are three main types of monastics. Those who live in monasteries under a common rule are coenobitic. Each monastery may formulate its own rule, and although there are no religious orders in Orthodoxy some respected monastic centers such as Mount Athos are highly influential. Eremitic monks, or hermits, are those who live solitary lives. Hermits might be associated with a larger monastery but living in seclusion some distance from the main compound, and in such cases the monastery will see to their physical needs while disturbing them as little as possible. They often live in the most extreme conditions and practice the strictest asceticism. In order to become a hermit, it is necessary for the monk or nun to prove themselves to be worthy enough to their superior clergy. In between are those in semi-eremetic communities, or sketes, where one or two monks share each of a group of nearby dwellings under their own rules and only gather together in the central chapel, or kyriakon, for liturgical observances.

The spiritual insight gained from their ascetical struggles make monastics preferred for missionary activity. Bishops are often chosen from among monks, and those who are not generally receive the monastic tonsure before their consecrations.

Many (but not all) Orthodox seminaries are attached to monasteries, combining academic preparation for ordination with participation in the community's life of prayer. Monks who have been ordained to the priesthood are called hieromonk (priest-monk); monks who have been ordained to the deaconate are called hierodeacon (deacon-monk). Not all monks live in monasteries, some hieromonks serve as priests in parish churches thus practising "monasticism in the world".

For the Orthodox, Father is the correct form of address for monks who have been tonsured to the rank of Stavrophore or higher, while Novices and Rassophores are addressed as Brother. Similarly, Mother is the correct form of address for nuns who have been tonsured to the rank of Stavrophore or higher, while Novices and Rassophores are addressed as Sister. Nuns live identical ascetic lives to their male counterparts and are therefore also called monachoi (monastics) or the feminine plural form in Greek, monachai, and their common living space is called a monastery.

Holy Orders

Since its founding, the Church spread to different places, and the leaders of the Church in each place came to be known as episkopoi (overseers, plural of episkopos, overseer — Gr. ἐπίσκοπος), which became " bishop" in English. The other ordained roles are presbyter (Gr. πρεσβύτερος, elder), which became "prester" and then " priest" in English, and diakonos (Gr. διάκονος, servant), which became " deacon" in English (see also subdeacon). There are numerous administrative positions in the clergy that carry additional titles. In the Greek tradition, bishops who occupy an ancient See are called Metropolitan, while the lead bishop in Greece is the Archbishop. Priests can be archpriests, archimandrites, or protopresbyters. Deacons can be archdeacons or protodeacons as well. The position of deacon is often occupied for life. The deacon also acts as an assistant to a bishop.

The Orthodox Church has always allowed married priests and deacons, provided the marriage takes place before ordination. In general, parish priests are to be married as they live in normal society (that is, "in the world" and not a monastery) where Orthodoxy sees marriage as the normative state. Unmarried priests usually live in monasteries since it is there that the unmarried state is the norm, although it sometimes happens that an unmarried priest is assigned to a parish. Widowed priests and deacons may not remarry, and it is common for such a member of the clergy to retire to a monastery (see clerical celibacy). This is also true of widowed wives of clergy, who often do not remarry and may become nuns if their children are grown. Bishops are always celibate. Although Orthodox consider men and women equal before God ( Gal. 3:28), only men who are qualified and have no canonical impediments may be ordained bishops, priests, or deacons.

Anointing with Holy Oil

Anointing, or Holy Unction, is one of the many mysteries administered by the Orthodox Church. The Mystery is far more common in the Orthodox Church than it had traditionally been in the Roman Catholic Church (until recent years). In both Churches today it is not reserved for the dying or terminally ill, but for all in need of spiritual or bodily healing. In Orthodoxy, however, it is also offered annually on Great Wednesday to all believers. It is often distributed on major feast days, or any time the clergy feel it necessary for the spiritual welfare of its congregation.

According to Orthodox teaching Holy Unction is based on James 5:14-15:

Is anyone among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer of faith will save the sick, and the Lord will raise him up. And if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven.

History

The early Church

Christianity first spread in the predominantly Greek-speaking eastern half of the Roman Empire. Paul and the Apostles traveled extensively throughout the Empire, establishing Churches in major communities, with the first Churches appearing in Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem, and then the two political centres of Rome and Constantinople. Orthodox believe an Apostolic Succession was established; this played a key role in the Church's view of itself as the preserver of the Christian community. Systematic persecution of Christians stopped in 313 when Emperor Constantine the Great proclaimed the Edict of Milan. From that time forward, the Byzantine Emperor exerted various degrees of influence over the church (see Caesaropapism). This included the calling of the Ecumenical Councils to resolve disputes and establish church dogma on which the entire church would agree. Sometimes Patriarchs (often of Constantinople) were deposed by the emperor; at one point emperors sided with the iconoclasts in the eighth and ninth centuries.

Ecumenical councils

Several Ecumenical Councils were held between 325 (the First Council of Nicaea) and 787 (the Second Council of Nicaea), which to Orthodox constitute the definitive interpretation of Christian dogma. Orthodox thinking differs on whether the Fourth and Fifth Councils of Constantinople were properly Ecumenical Councils, but the majority view is that they were merely influential, and not bindingly dogmatic.

Orthodox Christian culture reached its golden age during the high point of Byzantine Empire and continued to flourish in Russia, after the fall of Constantinople. Numerous autocephalous churches were established in Eastern Europe and Slavic areas.

The Orthodox churches with the largest number of adherents in modern times are the Russian and the Romanian Orthodox churches. The most ancient of the Orthodox churches of today are the Churches of Constantinople, Alexandria (which includes all of Africa, Georgia, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

The Roman/Byzantine Empire

Several doctrinal disputes from the 4th century onwards led to the calling of Ecumenical councils. The Church in Egypt (Patriarchate of Alexandria) split into two groups following the Council of Chalcedon ( 451), over a dispute about the relation between the divine and human natures of Jesus. Eventually this led to each group having its own Patriarch (Pope). Those that remained in communion with the other patriarchs were called "Melkites" (the king's men, because Constantinople was the city of the emperors) [not to be confused with the Melkite Catholics of Antioch], and are today known as the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria, until recently led by Pope Petros VII. Those who disagreed with the findings of the Council of Chalcedon are today known as the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria, led by Pope Shenouda III. There was a similar split in Syria. Those who disagreed with the Council of Chalcedon are sometimes called " Oriental Orthodox" to distinguish them from the Eastern Orthodox, who accepted the Council of Chalcedon. Oriental Orthodox are also sometimes referred to as " monophysites", "non-Chalcedonians", or "anti-Chalcedonians", although today the Oriental Orthodox Church denies that it is monophysite and prefers the term " miaphysite", to denote the "joined" nature of Jesus. Both the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches formally believe themselves to be the continuation of the true church and the other fallen into heresy, although over the last several decades there has been some reconciliation.

In the 530s the Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) was built in Constantinople under emperor Justinian I.

The seven ecumenical councils

Eastern Orthodox Christianity recognizes only these seven ecumenical councils.

- The first of the Seven Ecumenical Councils was that convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine at Nicea in 325, condemning the view of Arius that the Son is a created being inferior to the Father.

- The Second Ecumenical Council was held at Constantinople in 381, defining the nature of the Holy Spirit against those asserting His inequality with the other persons of the Trinity.

- The Third Ecumenical Council is that of Ephesus in 431, which affirmed that Mary is truly "Birthgiver" or "Mother" of God ( Theotokos), contrary to the teachings of Nestorius.

- The Fourth Ecumenical Council is that of Chalcedon in 451, which affirmed that Jesus is truly God and truly man, without mixture of the two natures, contrary to Monophysite teaching.

- The Fifth Ecumenical Council is the second of Constantinople in 553, interpreting the decrees of Chalcedon and further explaining the relationship of the two natures of Jesus; it also condemned the teachings of Origen on the pre-existence of the soul, etc.

- The Sixth Ecumenical Council is the third of Constantinople in 681; it declared that Christ has two wills of his two natures, human and divine, contrary to the teachings of the Monothelites.

- The Seventh Ecumenical Council was called under the Empress Regent Irene in 787, known as the second of Nicea. It affirmed the making and veneration of icons, while also forbidding the worship of icons and the making of three-dimensional statuary. It reversed the declaration of an earlier council that had called itself the Seventh Ecumenical Council and also nullified its status (see separate article on Iconoclasm). That earlier council had been held under the iconoclast Emperor Constantine V. It met with more than 340 bishops at Constantinople and Hieria in 754, declaring the making of icons of Jesus or the saints an error, mainly for Christological reasons.

The Oriental Orthodox

As noted above, Eastern Orthodoxy strives to keep the faith of the aforementioned seven Ecumenical Councils. In contrast, the term " Oriental Orthodoxy" refers to the churches of Eastern Christian traditions that keep the faith of only the first three ecumenical councils — the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus — and rejected the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon. Thus, "Oriental Orthodox" churches are distinct from the churches that collectively refer to themselves as "Eastern Orthodox". As well, there are the " Nestorian" churches, which are Eastern Christian churches that keep the faith of only the first two ecumenical councils, i.e., the First Council of Nicaea and the First Council of Constantinople.

The Great Schism

In the 11th century the Great Schism took place between Rome and Constantinople, which led to separation of the Church of the West, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Eastern Orthodox Church. There were doctrinal issues like the filioque clause and the authority of the Pope involved in the split, but these were exacerbated by cultural and linguistic differences between Latins and Greeks.

The final breach is often considered to have arisen after the sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. The sacking of the Church of Holy Wisdom and establishment of the Latin Empire in 1204 is viewed with some rancour to the present day. In 2004, Pope John Paul II extended a formal apology for the sacking of Constantinople in 1204; the apology was formally accepted by Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople. Many things that were stolen during this time: relics, riches, and many other items, are still held in various Catholic churches in Western Europe.

In 1453, the Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottoman Empire. By this time Egypt had been under Muslim control for some seven centuries, but Orthodoxy was very strong in Russia which had recently acquired an autocephalous status; and thus Moscow called itself the Third Rome, as the cultural heir of the Constantinople. Under Ottoman rule, the Greek Orthodox Church acquired substantial power. The ecumenical patriarch was the religious and administrative ruler of the entire "Greek Orthodox nation" (Ottoman administrative unit), which encompassed all the Eastern Orthodox subjects of the Empire. However, the number of Orthodox members in present-day Turkey have been reduced to a few thousand since the birth of the present-day secular state due to restrictive laws and practices enacted in the 1920s and 1970s.

Conversion of East and South Slavs

In the ninth and tenth centuries, Orthodoxy made great inroads into Eastern Europe, including Kievan Rus'. This work was made possible by the work of the Byzantine saints Cyril and Methodius. When Rastislav, the king of Moravia, asked Byzantium for teachers who could minister to the Moravians in their own language, Byzantine emperor Michael III chose these two brothers. As their mother was a Slav from the hinterlands of Thessaloniki, Cyril and Methodius spoke the local Slavonic vernacular and translated the Bible and many of the prayer books. As the translations prepared by them were copied by speakers of other dialects, the hybrid literary language Old Church Slavonic was created. Originally sent to convert the Slavs of Great Moravia, Cyril and Methodius were forced to compete with Frankish missionaries from the Roman diocese. Their disciples were driven out of Great Moravia in AD 886.

Methodius later went on to convert the Serbs.

Some of the disciples, namely St. Kliment, St. Naum who were of noble Bulgarian descent and St. Angelaruis, returned to Bulgaria where they were welcomed by the Bulgarian Tsar Boris I who viewed the Slavonic liturgy as a way to counteract Greek influence in the country. In a short time the disciples of Cyril and Methodius managed to prepare and instruct the future Slav Bulgarian clergy into the Glagolitic alphabet and the biblical texts and in AD 893, Bulgaria expelled its Greek clergy and proclaimed the Slavonic language as the official language of the church and the state. The success of the conversion of the Bulgarians facilitated the conversion of other East Slavic peoples, most notably the Rus', predecessors of Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians.

The missionaries to the East and South Slavs had great success in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin as the Roman priests did, or Greek. Today the Russian Orthodox Church is the largest of the Orthodox Churches.

The Church in North America

Russian traders settled in Alaska during the 1700s, and Greek laborers, brought in by a British adventurer and entrepreneur, formed a colony in what is now New Smyrna, Florida beginning in 1754. In 1740, a Divine Liturgy was celebrated on board a Russian ship off the Alaskan coast. In 1794 the Russian Orthodox Church sent missionaries -- among them Saint Herman of Alaska -- to establish a formal mission in Alaska. Their missionary endeavors contributed to the conversion of many Alaskan natives to the Orthodox faith. A diocese was established, whose first bishop was Saint Innocent of Alaska. The headquarters of this North American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church was moved from Alaska to California around the mid-19th century.

It was moved again in the last part of the same century, this time to New York. This transfer coincided with a great movement of Uniates to the Orthodox Church in the eastern United States. This movement, which increased the numbers of Orthodox Christians in America, resulted from a conflict between John Ireland, the politically powerful Roman Catholic Archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota; and Alexis Toth, an influential Ruthenian Catholic priest. Archbishop Ireland's refusal to accept Fr. Toth's credentials as a priest induced Fr. Toth to return to the Orthodox Church of his ancestors, and further resulted in the return of tens of thousands of other Uniate Catholics in North America to the Orthodox Church, under his guidance and inspiration. For this reason, Ireland is sometimes ironically remembered as the "Father of the Orthodox Church in America." These Uniates were received into Orthodoxy into the existing North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church. At the same time large numbers of Greeks and other Orthodox Christians were also immigrating to America. At this time all Orthodox Christians in North America were united under the omophorion (Church authority and protection) of the Patriarch of Moscow, through the Russian Church's North American diocese. The unity was not merely theoretical, but was a reality, since there was then no other diocese on the continent. Under the aegis of this diocese, which at the turn of the century was ruled by Bishop (and future Patriarch) Tikhon, Orthodox Christians of various ethnic backgrounds were ministered to, both non-Russian and Russian; a Syro-Arab mission was established in the episcopal leadership of Saint Raphael of Brooklyn, who was the first Orthodox bishop to be consecrated in America.

The Russian Orthodox Church was devastated by the Bolshevik Revolution. One of its effects was a flood of refugees from Russia to the United States, Canada, and Europe. Among those who came were Orthodox lay people, deacons, priests, and bishops. In 1920 Patriarch Tikhon issued an ukase (decree) that dioceses of the Church of Russia that were cut off from the governance of the highest Church authority (i.e. the Patriarch) should continue independently until such time as normal relations with the highest Church authority could be resumed; and on this basis, the North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church (known as the "Metropolia") continued to exist in a de facto autonomous mode of self-governance. The financial hardship that beset the North American diocese as the result of the Russian Revolution resulted in a degree of administrative chaos, with the result that other national Orthodox communities in North America turned to the Churches in their respective homelands for pastoral care and governance. Between the World Wars the Metropolia coexisted and at times cooperated with an independent synod later known as Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), sometimes also called the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. The two groups eventually went their separate ways. ROCOR, which moved its headquarters to North America after the Second World War, claimed but failed to establish jurisdiction over all parishes of Russian origin in North America. The Metropolia, as a former diocese of the Russian Church, looked to the latter as its highest church authority, albeit one from which it was temporarily cut off under the conditions of the communist regime in Russia. After resuming communication with Moscow in early 1960s, and being granted autocephaly in 1970, the Metropolia became known as the Orthodox Church in America (OCA, though referred to rarely as "TOCA"). . However, recognition of this autocephalic status is not universal, as the Ecumenical Patriarch (under whom is the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America) and some other jurisdictions have not officially accepted it. The reasons for this are complex; nevertheless the Ecumenical Patriarch and the other jurisdictions remain in communion with the OCA.

Today there are many Orthodox churches in the United States and Canada that are still bound to the Greek, Antiochian, or other overseas jurisdictions; in some cases these different overseas jurisdictions will have churches in the same U.S. city. However, there are also many "pan-orthodox" activities and organizations, both formal and informal, among Orthodox believers of all jurisdictions. One such organization is the Standing Conference of Orthodox Bishops in America (SCOBA), the Standing Conference of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas, which comprises North American Orthodox bishops from nearly all jurisdictions. (See list of Orthodox jurisdictions in North America.)

In June of 2002, the Antiochian Orthodox Church granted self-rule to the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America. Some observers see this as a step towards greater organizational unity in North America.

During the past 50 years there have come into existence in North America a number of Western Rite Orthodox parishes. These are sometimes labelled " Western Orthodox Churches," but this term is not generally used by Orthodox Christians of Eastern or Western rite. These are Orthodox Christians who use the Western forms of liturgy ( Latin Rites) yet are Orthodox in their theology. The Antiochian Orthodox Church and ROCOR both have Western Rite parishes.

According to some estimates, there are over 2000 Orthodox parishes in United States. Roughly half of these belong to OCA, Greek and Antiochian Orthodox Churches, and the rest are divided among other jurisdictions.

The estimates of numbers of Eastern Orthodox adherents in North America vary considerably depending on methodology ( as well as the definition of the term "adherent" ) and generally fall in range from 1.2 million to 6 million.

Eastern Orthodoxy has had a history in China and East Asia as well.

The Church today

The various autocephalous and autonomous churches of the Orthodox Church are distinct in terms of administration and local culture, but for the most part exist in full communion with one another, with exceptions such as lack of relations between the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR) and the Moscow Patriarchate (the Orthodox Church of Russia) dating from the 1920s and due to the subjection of the latter to the hostile Soviet regime. However, attempts at reconciliation are being made between the ROCOR and the Moscow Patriarchate with the ultimate purpose of reunification. Further tensions exist in the philosophical differences between the New Calendarists and the Moderate Old Calendarists.