Paul of Tarsus

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Religious figures and leaders

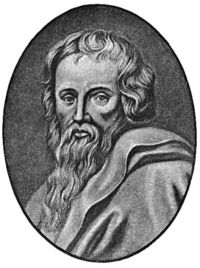

Paul of Tarsus (d. c. 65), who called himself the Apostle to the Gentiles ( Romans 11:13, Galatians 2:8), together with Simon Peter was the most notable Early Christian missionaries. Unlike the Twelve Apostles, Paul did not know Jesus in life, though he claimed to have seen the resurrected Jesus ( 1 Cor 15:8-9). His own account of his conversion states only that he "received it [the Gospel] by revelation from Jesus Christ" ( Gal 1:11-12); according to Acts, his conversion was on the Road to Damascus.

He was the second most prolific contributor to the New Testament, after Luke the Evangelist. Fourteen letters are attributed to him, with varying degrees of confidence. These contain the earliest systematic account of Christian doctrine, and provide information on the life of the infant Church. His letters are arguably the oldest part of the New Testament. He also appears in the pages of the Acts of the Apostles, attributed to Saint Luke, so that it is possible to compare the account of his life in the Acts with his own account in his various letters. His letters are largely written to churches which he had founded or visited; he was a great traveller, visiting Cyprus, Asia Minor (modern Turkey), mainland Greece, Crete, and Rome bringing the gospel of Jesus Christ, first to Jews and then to Gentiles. His letters are full of expositions of what Christians should believe and how they should live; what he does not do is to tell his correspondents (or the modern reader) much about the life and teachings of Jesus. His most explicit references are to the Last Supper ( 1 Cor 11:17-34), the crucifixion and resurrection ( 1 Cor 15). His references to Jesus' teaching are likewise scant: that against divorce ( 1 Cor 7:10-16) and the commandment to love one another ( Romans 13:8-10, Gal 5:14); raising the question, still disputed, as to how consistent his version of the Christian faith is with that of the canonical Gospels of the Four Evangelists. (See below).

Paul's influence on Christian thinking has, arguably, been more significant than any other single New Testament author. His writings were taken up by non-orthodox groups (called heretics by orthodox Christians; such as Marcion and Valentinus). His influence on the main strands of Christian thought have been massive, from St. Augustine of Hippo to the controversies between Gottschalk and Hincmar of Reims, between Thomism and Molinism, Martin Luther, Calvin and the Arminians, Jansenism and the Jesuit theologians and even to the German church of the twentieth century through the writings of the scholar Karl Barth, whose commentary on the Letter to the Romans had a political as well theological impact.

St. Paul is the patron saint of Malta and the City of London, and has also had several cities named in his honour (including São Paulo, Brazil, and Saint Paul, Minnesota).

Early life

According to his own account, Paul was born in Tarsus in Cilicia in Minor Asia with the name Saul, "an Israelite of the tribe of Benjamin, circumcised on the eighth day" (Phil.3:5). Acts records that Paul was a Roman citizen—a privilege he used a number of times in his defense, appealing convictions in Judea to Rome (Acts 22:25 and 27–29). According to Acts 22:3, he studied in Jerusalem under the Rabbi Gamaliel, well known in Paul's time. He supported himself during his travels and while preaching — a fact he alludes to a number of times (e.g., 1 Cor 9:13–15); according to Acts 18:3, he worked as a tentmaker.

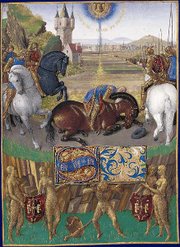

He first appears in the pages of the New Testament as a witness to the martyrdom of Saint Stephen ( Acts 7:57-8:3). He was, as he described himself, a persistent persecutor of the Church ( 1 Cor 15:9, Gal 1:13), almost all of whose members were Jewish or Jewish proselytes, until his experience on the Road to Damascus which resulted in his conversion. According to Acts, after a bolt of light from the skies brighter than the sun, he heard the voice of Jesus saying to him in Aramaic: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? ." (Acts|9: 5) RSV). He fell to the ground and found himself blinded, a condition which was not relieved until he had been taken to Damascus where Ananias laid hands on him, cured him, and baptised him. There are three versions of the story told in Acts: the first is a description of the event ( 9:1-19a); the second is Paul’s account of the event in Aramaic before the crowd in Jerusalem ( 22:1-22); the third is Paul's account before King Agrippa II ( 26:1-24). His own account, in his letter to the Galatians ( 1:11-24), is more circumspect, emphasising his independence from the apostles in Jerusalem but not describing his conversion in any detail.

In trying to reconstruct the events of Paul's life, it is necessary to compare Acts and the letters. Different views are held as to the reliability of the former, whose usefulness is strongly disputed by some scholars. Even allowing for omissions in St. Paul’s own account, which is found particularly in Galatians, it is difficult, even impossible in places, to reconcile his account with that in Acts (as is shown below). It is also difficult to ascertain when the letters were written. Acts makes no reference to his letter writing and it never quotes any of his letters. Omissions, of course, present less of a problem than apparent contradictions. The general line taken is to prefer Paul's own account, from his authentic letters, to that of Acts.

Some argue that the historicity of Acts may be discerned from within the book itself by the so-called "we" passages. In Acts 16:11, the descriptions of events suddenly change from "he" and "they" to "we", as if the narrator Luke himself had joined them; these "he" sections include the trip to Philippi and the conversion of Lydia. Thereafter, the narrator appears to be present with Paul as he sails from Philippi to Troas to Jerusalem and again on the journey to Rome. (See below)

Mission

Following his stay in Damascus after his conversion, where he was baptised, Paul says that he first went to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus ( Gal 1:17). According to Acts, his preaching in the local synagogues got him into trouble there, and he was forced to escape, being let down over the wall in a basket (Acts 9:23). He describes in Galatians, how three years after his conversion, he went to Jerusalem, where he met James, and stayed with Simon Peter for fifteen days ( Gal 1:13–24). According to Acts, he apparently attempted to join the disciples and was accepted only owing to the intercession of Barnabas – they were all understandably afraid of him as one who had been a persecutor of the Church (Acts 9: 26-27). Again, according to Acts, he got into trouble for disputing with "Hellenists" (Greek speaking Jews and Gentile "God-fearers") and so he was sent back to Tarsus.

We do not know exactly what happened in the fourteen years that elapsed before he went again to Jerusalem. At the end of this time, Barnabas went to find Saul and brought him back to Antioch (Acts 11:26). As he had been the object of suspicion by the Christians at Jerusalem, it is impossible to deduce how he might have been received when he returned to Tarsus and if he stayed without incident.

When a famine occurred in Judaea (which can be dated to around AD 44), help was sent by the hands of Barnabas and Saul (as Paul was then still called (Acts 11:30)); Saul then returned to Antioch. According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative centre for Christians, following the dispersion after the death of Stephen. In Antioch, the followers of Jesus were first called Christians.

First Missionary Journey

According to Acts 13-14 , Barnabas took Saul on what is often called the First Missionary Journey which took them to the towns of southern Turkey: Perga, Antioch, Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe. However, Paul's own letters only mention that he preached in Syria and Cilicia (Gal 1:18–20). Acts records that Paul later "went through Syria and Cilicia, strengthening the churches" (15:41), but it does not explicitly state who founded the churches or when they were founded.

The "Council of Jerusalem"

According to Acts 15, Paul and the apostles held a meeting at Jerusalem at which they discussed the question of circumcision of Gentile Christians; scholars usually date this meeting around AD 50. Traditionally, this meeting is called the Council of Jerusalem, though nowhere is it called so in any of the biblical texts.

Paul and the apostles apparently met at Jerusalem several times; determining the order of these meetings has direct bearing upon the dating of several of Paul's letters, including Galatians. Unfortunately, there is some difficulty in determining the sequence of the meetings and exact course of events. Some Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, some meetings are mentioned in Paul's letters, and some are mentioned in both. For example, in Galatians Paul makes no separate mention of the Jerusalem visit implied in Acts 11:27-30 when he and Barnabas brought famine relief to Judea. In Galatians 2:1, Paul describes a possible second visit to Jerusalem as a private occasion, whereas Acts describes a public meeting in Jerusalem addressed by James at its conclusion. Thus some scholars think that Paul in Galatians is referring to the meeting in Acts 11 (the 'famine visit') and that the letter to the Galatians was written after the men had come to Antioch demanding circumcision and before the Council of Jerusalem, the public meeting, had taken place— or even as he was setting out for it— this interpretation would make Galatians the earliest letter to be written (it is generally dated between 48 and 55). If the meeting was private, Luke’s informants might have had no knowledge of it; however, it could not have taken place fourteen years after the first encounter (or seventeen from the date of Paul’s conversion), because the famine relief took place in the reign of King Herod Agrippa who died in AD 44. That would put Paul's conversion at AD 27, before Jesus' death! (The crucifixion is generally dated between AD 28 and 36, 28 being the year that John the Baptist began his ministry according to Luke 3, 36 being the year of Pilate's recall to Rome; the traditional date is c. 33.) In any case the famine did not develop until after Herod's death, reaching its greatest severity in 48 AD. Many other conjectures have been offered: fourteen years should be four; Acts 11 and 15 are two alternative accounts of the same visit; the visit is recorded in Acts 18:22. If there was a public rather than a private meeting, it seems likely that it look place after Galatians was written.

According to Acts, Paul and Barnabas were appointed to go to Jerusalem to speak with the apostles and elders and were welcomed by them. The key question raised (in both Acts and Galatians and which is not in dispute) was whether Gentile converts needed to be circumcised Acts 15:2ff; Gal.2:1ff). Paul states that he had attended "in response to a revelation and to lay before them the gospel that I preached among the Gentiles" (Gal 2:2). Peter publicly reaffirmed a decision he had made previously (see Acts 10 and 11), proclaiming: "[God] put no difference between us and them, purifying their hearts by faith" (Acts15:9), echoing an earlier statement: "Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons" (Acts10:34). James concurred: "We should not trouble those of the Gentiles who are turning to God" (Acts15:19–21), and a letter (later known as the Apostolic Decree) was sent back with Paul enjoining them from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals, and from sexual immorality (Acts 15:29), which some consider to be Noahide Law.

Despite the agreement they achieved at the meeting as understood by Paul, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter (accusing him of Judaizing, also called the "Incident at Antioch") over his reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch. Paul later wrote: "I opposed [Peter] to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong" and said to the apostle: "You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?" (Gal. 2:11–14). Paul also mentioned that even Barnabas sided with Peter. Acts does not record this event, saying only that "some time later", Paul decided to leave Antioch (usually considered the beginning of his "Second Missionary Journey", (Acts15:36–18:22) with the object of visiting the believers in the towns where he and Barnabas had preached earlier, but this time without Barnabas. At this point the Galatians witness ceases. Thereafter, only fragmentary information about Paul survives.

Second Missionary Journey

Following a dispute between Paul and Barnabas over whether they should take John Mark with them, they went on separate journeys ( Acts 15:36–41) — Barnabas with John Mark, and Paul with Silas. Following Acts 16:1-18:22, Paul and Silas went to Derbe and Lystra, the Phrygia and northern Galatia, to Troas, when, inspired by a vision they set off for Greece. At Philippi they met and brought to faith Lydia, whom they baptised together with her family; there Paul was also arrested and badly beaten. According to Acts, Paul then set off for Thessalonica. This accords with Paul’s own account (1 Thess. 2:2), though some question that having been in Philippi only "some days", Paul could found a church based on Lydia’s house;it may have may have been founded earlier by someone else. According to Acts, Paul then came to Athens where he gave his speech in the Areopagus; in this speech, he told Athenians that the " Unknown God" to whom they had a shrine was in fact "known", as the God who had raised Jesus from the dead. (Acts 17:16–34). Thereafter Paul travelled to Corinth, where he settled for three years and where he may have written 1 Thessalonians, possibly the earliest of his surviving letters. At Corinth, ( 18:12–17), the "Jews united" and charged Paul with "persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law"; the proconsul Gallio then judged that it was a minor matter not worth his attention and dismissed the charges. "Then all of them (Other ancient authorities read all the Greeks) seized Sosthenes, the official of the synagogue, and beat him in front of the tribunal. But Gallio paid no attention to any of these things." ( 18:17 NRSV) From an inscription in Delphi that mentions Gallio, the year of the hearing is known to be AD 52, which aids in reconstructing the chronology of Paul's life.

Third Missionary Journey

Following this hearing, Paul continued his preaching, usually called his "Third Missionary Journey" ( Acts 18:23–21:26), travelling again through Asia Minor and Macedonia, to Antioch and back. He caused a great uproar in the theatre in Ephesus, where local silversmiths feared loss of income due to Paul's activities. Their income relied on the sale of silver statues (called by Paul "idols") of the goddess Artemis, whom they worshipped; the resulting mob almost killed Paul (Acts 19:21–41) and his companions. Later, as Paul was passing near Ephesus on his way to Jerusalem, Paul chose not to stop, since he was in haste to reach Jerusalem by Pentecost. The church here, however, was so highly regarded by Paul that he called the elders to Miletus to meet with him (Acts 20:16–38).

Arrest and death

Upon Paul's arrival in Jerusalem, he gave account of his work of bringing Gentiles to faith to the apostles. According to Acts, James the Just confronted Paul with the charge that he was teaching the Jews to ignore the law and asked him to demonstrate that he was a law-abiding Jew by taking a Nazirite vow (21:26). However, that Paul did so is difficult to reconcile with his personally expressed attitude both in Galatians and Philippians, where he utterly opposed any idea that the law was binding on Christians, declaring that even Peter did not live by the law ( Gal 2:14). Various attempts have been made to reconcile Paul's views as expressed in his different letters and in Acts, notably the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia article on Judaizers states:

- "Paul, on the other hand, not only did not object to the observance of the Mosaic Law, as long as it did not interfere with the liberty of the Gentiles, but he conformed to its prescriptions when occasion required ( 1 Cor 9:20). Thus he shortly after [the Council of Jerusalem] circumcised Timothy ( Acts 16:1–3), and he was in the very act of observing the Mosaic ritual when he was arrested at Jerusalem ( 21:26 sqq.)".

In any case, after about a week after Paul had taken his vow at the temple, some Jews from "Asia" (Asia Minor or modern Turkey, Paul's homeland) spotted him in Jerusalem and stirred up the crowd shouting: "Men of Israel, help us! This is the man who teaches all men everywhere against our people and our law and this place. And besides, he has brought Greeks into the temple area and defiled this holy place." ( 21:28). The crowd was about to kill Paul but the Roman guard rescued him, and after an unsuccessful speech in Aramaic ( 21:37-22:22), imprisoned him in Caesarea. Paul claimed his right as a Roman citizen to be tried in Rome, but owing to the inaction of the governor Antonius Felix, Paul languished in confinement at Caesarea for two years. When a new governor (Porcius Festus) took office, he held a hearing and sent Paul by sea to Rome. According to Acts, Paul spent another two years in Rome under house arrest, "Boldly and without hindrance he preached the kingdom of God and taught about the Lord Jesus Christ." ( 28:30-31) Of his detention in Rome, Philippians provides some additional support. It was clearly written from prison and references to the "praetorian guard" and "Caesar’s household" may suggest that it was written from Rome.

Whether Paul died in Rome or was able to go to Spain as in his letter to the Romans (Rom. 15:22-7) he hoped, is uncertain. Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote in the fourth century, states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero. This event has been dated either to the year 64, when Rome was devastated by a fire, or a few years later, to AD 67. An ancient liturgical solemnity of Peter and Paul, celebrated on 29 June, could reflect the day of martyrdom, and many ancient sources articulated the tradition that Peter and Paul died on the same day (and possibly the same year). Chronologically, the tradition that Paul was martyred in Rome is not inconsistent with the suggested mission to Spain. St. Clement of Rome, writing thirty years later says that Paul went to "the the limits of the west". If the Pastoral Epistles are genuine, which a number of modern scholars have doubted, he could have revisited Greece and Asia Minor after his trip to Spain, and might then have been arrested in Troas (2 Tim. 4:13) and taken to Rome and executed.

The traditional story is that Paul died as a martyr in Rome and his body was interred with Saint Peter's ad Catacumbas by the via Appia. According to this view, his body remained there until moved by Lucina and Pope Cornelius into the crypts of Lucina. One Gaius, who wrote during the time of Pope Zephyrinus, mentions Paul's tomb as standing on the Via Ostensis, and the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls consistently claimed to be built upon Paul's tomb. Supporters of this view point to the recent archaeological discovery of a tomb under the basilica bearing Paul's name, the titles "apostle" and "martyr", and which date to antiquity.

According to Bede in his Ecclesiastical History, Pope Vitalian in 665 gave Paul's relics (including a cross made from his prison chains) from the crypts of Lucina to Oswy, British King of Northumbria. However, Bede's use of the word "relic" was not limited to corporal remains.

Writings

Authorship

Of the fourteen letters attributed to St. Paul, one, Hebrews, was disputed from an early date and is generally not thought to have been written by him. As for the rest, there is little or no dispute about the authorship of Romans, First Corinthians, Second Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, First Thessalonians, and Philemon.

The authenticity of Colossians has been questioned on the grounds that it contains an otherwise unparalleled description (amongst his writings) of Jesus as ‘the image of the invisible God’, a Christology found elsewhere only in St. John’s gospel. Nowhere is there a richer and more exalted estimate of the position of Christ than here. On the other hand, the personal notes in the letter connect it the Philemon, unquestionably the work of Paul. More problematic is Ephesians a very similar letter to Colossians, but which reads more like a manifesto than a letter. It is almost entirely lacking in personal reminiscences. Its style is unique; it lacks the emphasis on the cross to be found in other Pauline writings; reference to the Second Coming is missing; and Christian marriage is exalted in a way which contrasts with the grudging reference in 1 Cor 7:8-9. Finally it exalts the Church in a way suggestive of a second generation of Christians, ‘built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets’ now past. The defenders of its Pauline authorship argue that it was intended to be read by a number of different churches and that it marks the final stage of the development of St. Paul's thinking.

The Pastoral Epistles, 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus have likewise been put in question as Pauline works only in modern times. Three main reasons are advanced; first, their difference in vocabulary, style and theology from St. Paul’s acknowledged writings; secondly the difficulty in fitting them into St Paul’s biography as we have it. They, like Colossians and Ephesians, were written from prison but suppose St. Paul’s release and travel thereafter. Finally, the concerns expressed are very much the practical ones as to how a church should function. They are more about maintenance than about mission.

Views are advanced on the basis of the balance of opinion of scholars, but there is no certainty and some may think that questions of authorship do not affect the authority of the letters.

Two further epistles attributed by some to Paul (since some of the prior epistles mention them) have been lost: Epistle to the Alexandrians (lost), of which nothing is known letter apart from a brief mention in the Muratorian fragment that claims it was a forgery; the Epistle to the Macedonians which is lost.

Paul on Jesus

As already stated, little can be deduced about the earthly life of Jesus from St. Paul’s letters. He mentions specifically only the Last Supper (1 Cor. 11:23ff) his death by crucifixion (1 Cor :2:2; Phil. 2:8) and his resurrection (Phil. 2:9) . Instead Paul concentrates on the nature of the Christian’s relationship with Christ and, in particular, in Christ’s saving work. In St. Mark’s gospel, Jesus is recorded as saying that he was to ‘give up his life as a ransom for many’. St. Paul’s account of his idea of a saving act is more fully articulated, albeit in various places in his letters, but most notably in his letter to the Romans.

What Christ has achieved for those who believe in him is variously described: as sinners under the law, they are ‘‘ justified by his grace as a gift’’; they are ‘‘ redeemed’’ by Jesus who was put forward by God as ‘expiation’; they are ‘’reconciled’’ by his death. The gift (grace) is to be received in faith. (Rom 3:24f; Rom 5: 9). These three images have been the subject of detailed examination.

Justification derives from the law courts. Those who are justified are acquitted of an offence. Since the sinner is guilty, he or she can only be acquitted by someone else, Jesus, standing in for them, which has led many Christians to believe in the teaching known as the doctrine of substitutionary atonement. The sinner is, in St. Paul’s words ‘justified by faith’ (Rom. 5:1).]], that is, by adhering to Christ, the sinner becomes ‘at one’ with Christ in his death and resurrection (hence the word ‘atonement’). Acquittal, however, is achieved not on the grounds that Christ was innocent (though he was) and that we share his innocence but on the grounds of his sacrifice i.e. his crucifixion), i.e. his innocent undergoing of punishment on behalf of sinners who should have suffered divine retribution for their sins. They deserved to be punished and he took their punishment. They are justified by his death, and now ‘so much more we are saved by him from divine retribution’ (Rom. 5: 9)

For an understanding of the meaning of faith as that which justifies, St. Paul turns to Abraham, who trusted God’s promise that he would be father of many nations. Abraham preceded the giving of the law on Mount Sinai. Thus law cannot save us; faith does. Abraham could not, of course, have faith in the living Christ but, in Paul’s view, ‘the gospel was preached to him beforehand’ (Gal. 3:8), which may be interpreted as part of Paul’s belief in the pre-existent Christ.

Redemption has a different origin, that of the freeing of slaves; it is similar in character as a transaction to the paying of a ransom, (mentioned in St. Mark) though the circumstances are different. Money was paid in order to set free a slave, one who was in the ownership of another. Here the price was the costly act of Christ’s death. On the other hand, no price was paid to anyone – St. Paul does not suggest, for instance, that the price be paid to the devil – though this has been suggested by learned writers, ancient and modern, such as Origen and St. Augustine, as a reversal of the Fall by which the devil gained power over humankind.

A third expression, Reconciliation, is about the making of friends which is, of course, a costly exercise where one has failed or harmed another . The making of peace (Col. 1:20) (Rom 5:9) is another variant of the same theme. Elsewhere (Eph. 2:14) he writes of Christ breaking down the dividing wall between Jew and Gentile, which the law constituted.

As to how a person appropriates this gift, St. Paul writes of a mystical union with Christ through baptism: ‘we who have been baptised into Christ Jesus were baptised into his death’(Rom. 6:4). He writes also of our being ‘in Christ Jesus’ and alternately, of ‘Christ in you, the hope of glory’. Thus, the objection that one person cannot be punished on behalf of another is met with the idea of the identification of the Christian with Christ through baptism.

These expressions, some of which are to be found in the course of the same exposition, have been interpreted by some scholars, such as the mediaeval teacher Peter Abelard and, much more recently, Hastings Rashdall as metaphors for the effects of Christ’s death upon those who followed him. (This is known as the subjective theory of the atonement. On this view, rather than writing a systematic theology, Paul is trying to express something inexpressible. According to Ian Markham, on the other hand, the letter to the Romans is ‘muddled’.

But others, ancient and modern, Protestant and Catholic, have sought to elaborate from his writing objective theories of the Atonement on which they have, however, disagreed. The doctrine of justification by faith alone was the major source of the division of western Christianity known as the Protestant Reformation which took place in the sixteenth century. Justification by faith was set against salvation by works of the law in this case, the payment of indulgences to the Church and even such good works as the corporal works of mercy. The result of the dispute, which undermined the system of endowed prayers and the doctrine of purgatory, was the creation of Protestant churches in Western Europe, set against the Roman Catholic Church. Solifidianism (sola fides), the name often given to these views, is associated with the works of Martin Luther (1483-1546) and his followers. With thisivew went the notion of Christ’s substitutionary atonement for human sin.

The various doctrines of the atonement have been associated with such theologians as Anselm, Calvin, and more recently Gustaf Aulen; none found their way into the Creeds. The substitutionary theory (above), in particular, has fiercely divided Christendom, some pronouncing it essential and others repugnant. The doctrine has thus been the focus of some of the ecumenical discussions between the Roman Catholic Church and both Lutheran churches and the Anglican Communion cf. A.R.C.I.C..

Further, because salvation could not be achieved by merit, Paul lays some stress on the notion of its being a free gift, a matter of Grace. Whereas grace is most often associated specifically with the Holy Spirit, in St. Pau's writing, grace is received through Jesus (Rom.1:5), , from God through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus (Rom.3:24) and especially in 2 Cor.13:14. On the other hand, the Spirit he describes as the Spirit of Christ (see below). The notion of free gift, not the subject of entitlement has been associated with belief in predestinationi.e. that God has chosen whom He wills to have mercy on and those whose will He has hardened (Rom. 9:18f.). This belief has been taught by many teachers of the church throughout the ages from Augustine to Calvin and is held by many Protestant churches to date. Those who resist the idea of God's will as being exercised arbitrarily have taken refuge in Paul's declaration that 'God has consigned all men to disobedience that he may have mercy on all' (Rom. 11:32) and his final agnosticism on the matter: 'How unsearchable are his judgements and how inscrutable his ways. (ibid. 11.33) The question remains a philosophical as well as the theological conundrum bought practically, we cannot know the will of God.

Paul's concern with what Christ had done, as described above, was matched by his desire to says also who he was (and is). In his letter to the Romans, he describes Jesus as the ‘ Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead’; in the letter to the Colossians, he is much more explicit, describing Jesus as ‘the image of the invisible God’, Col.1:15) as rich and exalted picture of Jesus as can be found anywhere in the New Testament (which is one reason why some doubt its authenticity) . On the other hand, in the undisputed Pauline letter to the Philippians, he describes Jesus as ‘in the form of God’ who ‘did not count equality with God as thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men he humbled himself and became obedient to death, even death on a cross…’

The Holy Spirit

Paul places much emphasis on the importance of the Spirit in the Christian life. He contrasts the spiritual and those thoughts and actions which are animal (of the flesh). The difficulty come sin determining how this affects action. The gift of the spirit was much associated in Gentile mind with the gift of ecstatic speech speaking in tongues and is connected in Acts with becoming a Christian, even before baptism. In considering the manifestations of the spirit, he is cautious. Thus, when discussing the gift of tongues in his first letter to the Corinthians (Chapter 14), as against the unintelligible words of ecstasy, he commends, by contrast, intelligibility and order: ecstasy may illuminate the practitioner; coherent speech will enlighten the hearer. Everything should be done decently and in order.

Secondly, the gift of the Spirit appears to have been interpreted by the Corinthians as a freedom from all constraints, and in particular the law. Paul, on the contrary, argues that not all things permissible are good; eating meats that have been offered to pagan idols, frequenting pagan temples, orgiastic feasting; none of these things build up the Christian community, and may offend the weaker members. On the contrary, the Spirit was a uniting force, manifesting itself through the common purpose expressed in the exercise of their different gifts (1 Cor. 12) He compares the Christian community to a human body, with its different limbs and organs, and the Spirit as the Spirit of Christ, whose body we are. The gifts range from administration to teaching; encouragement to healing; prophecy to the working of miracles. Its fruits are the virtues of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, faithfulness, gentleness and self control (Gal.5:22) . Love is the best way of all (1 Cor. 13)

Further, the new life is the life of the Spirit, as against the life of the flesh, which Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, so that one becomes a son of God. God is our Father and we are fellow heirs of Christ.

Relationship with Judaism

Paul was himself a Jew, but his attitude towards his co-religionists is not agreed amongst all scholars. He appeared to praise Jewish circumcision in Romans 3:1-2, said that circumcision didn't matter in 1 Cor 7:19 but in Galatians, accuses those who promoted circumcision of wanting to make a good showing in the flesh and boasting or glorying in the flesh in Gal 6:11-13. He also questions the authority of the law, see Antinomianism, and though he may have opposed observance by non-Jews he also opposed Peter for his partial observance.In a later letter, Phil 3:2, he is reported as warning Christians to beware the "mutilation" ( Strong's G2699) and to "watch out for those dogs". He writes that there is neither Jew nor Greek, but Christ in all and in all. On the other hand in Acts, as we have seen, he is described as submitting to taking a Nazirite vow, and earlier to having had Timothy circumcised to placate the Jews. He also wrote that among the Jews he became as a Jew in order to win Jews ( 1 Cor 9:20) and to the Romans: "So the law is holy, and the commandment is holy and just and good." ( Rom 7:12) The task of reconciling these different views is made more difficult because it is not agreed whether, for instance, Galatians is a very early or later letter. Likewise Philippians may have been written late, from Rome, but not everyone is agreed on this.

The background to the various arguments is the ongoing dispute over the observance of the law, which, as we have noticed, was with Jews but also with so-called Judaizing Gentile Christians. In Galatians and Philippians, St. Paul is emphatic that the law is of null effect; it only makes men and women aware of their sinfulness. His own sense of relief at discovering that what the law was incapable of doing, the risen Christ had done permeates his letters. The question of whether Christianity was a Jewish sect or included Gentiles, without their having to fully conform to Jewish ritual law was eventually answered pretty emphatically as the latter. ( but see "Council of Jerusalem above")

However, considerable disagreement at the time and subsequently has been raised as to the significance of ‘works of the law’. In the same letter in which Paul writes of justification by faith , he says of the Gentiles ‘It is not by hearing the law, but by doing it that men will be justified (same word) by God.’ (Rom. 2:12) Those who think Paul capable of inconsistency have judged him not to be a ‘Solifidianist’ himself; the more frequently taken line has been that he is merely demonstrating that both Jews and Gentiles are in the same condition of sin.

E. P. Sanders in 1977 reframed the context to make law-keeping and good works a sign of being in the Covenant (marking out the Jews as the people of God) rather than deeds performed in order to accomplish salvation, a pattern of religion he termed ‘covenantal nomism’. If Sanders' perspective is regarded as valid, the traditional Protestant understanding of the doctrine of justification may have needed rethinking; for the interpretive framework of Augustine of Hippo and Martin Luther, which had dominated Christian thinking for almost two millennia, was called into question.

Sanders's work has since been taken up by Professor James Dunn and N.T. Wright, Bishop of Durham, and the New Perspective has increased significantly in dominance in New Testament scholarship. Wright, noting the apparent discrepancy between Romans and Galatians, the former being much more positive about the continuing covenantal relationship between God and his ancient people, than the latter, contends that that works are not insignificant (Romans 2: 13ff) and that Paul distinguishes between works which is signs of ethnic identity and those which are a sign of obedience to Christ.

The resurrection

Paul appears to develop his ideas in response to the particular congregation to whom he is writing. The idea of the resurrection of the body was foreign to the Greek (i.e. Corinthian) mind; rather the soul would ascend apart from the body. The Jewish conception, on the other hand, was of the ‘exaltation’ of the body which was assumed into heaven. Neither fits easily into the descriptions of the risen Christ walking about as described in the gospels. The Corinthians appeared to believe, from what Paul writes, that Jesus had avoided death, but that his followers would not. He wants to make clear to them that Jesus died but overcame death and that unless he did so we could not hope to be raised from the dead; because he did so, we can (1 Cor. 15:12ff.).

However, the resurrected body is a glorified body and thus will not decay. He contrasts the old and the new body: the first being physical, the second spiritual; 'sown in dishonour, it is raised in glory; sown in weakness it is raised in power' (1 Cor. 15:42 (RSV) It is, in his view, a spiritual body which he envisages as if being put on over the old body of flesh; it is, in another image, like a tent which covers us so that ‘we may not be found naked (2 Cor. 5:3RSV)

Thirdly, Paul has a very corporate idea of the resurrection hope of the Christian community. The hope given to all who belong to Christ, includes those who have already died but who have been baptised vicariously by the baptism of others on their behalf – so that they may be included among the saved(1 Cor. 15:29); (whether or not St. Paul approved of the practice he was apparently prepared to use as part of his argument in favour of the resurrection of the dead).

The World to come

Paul’s teaching about the end of the world is expressed most clearly in his letters to the Christians at Thessalonica. Heavily persecuted, it appears that they had written asking him, first about those who had died already and secondly when they should expect the end. Paul regarded the age as passing and, in such difficult times, he therefore discouraged marriage. He assures them that the dead will rise first and be followed by those left alive (1 Thess. 4:16ff.) . This suggests an imminence of the end but he is unspecific about times and seasons, and encourages his hearers to expect a delay. The form of the end will be a battle between Jesus and ‘the man of lawlessness (2 Thess.2:3ff.RSV) whose conclusion is the triumph of Christ.

The delay in the coming of the end has been interpreted in different ways: on one view, St. Paul and the early Christians were simply mistaken; on another, that of Austin Farrer his presentation of a single ending can be interpreted to accommodate the fact that endings occur all the time and that, subjectively, we all stand an instant from judgement. the delay is also accounted for by God’s patience (2 Thess. 2:6)

As for the form of the end, the Catholic Encyclopedia presents two distinct ideas. First, universal judgement, with neither the good nor the wicked shall omitted ( Rom 14:10–12), nor even the angels ( 1 Cor 6:3). Second, and more controversially, judgment will be according to works, mentioned concerning sinners ( 2 Cor 11:15), the just ( 2 Tim 4:14), and men in general ( Rom 2:6–9). This latter characterization has been the subject of controversy among Reformed theologians, notably N. T. Wright.

Social views

Every letter of St. Paul includes pastoral advice which most often arises from the doctrines he has been propounding. They are not afterthoughts. Thus in his letter to the Romans, having reminded his readers that, like branches grafted onto the olive, they thesmelves, like the natural branches, the Jews, may be broken off if they fail to persist in faith. For that reason he appeal to them to offer themselves to God, and not to be conformed to the world. They must use their gifts as part of the body which they are. He invites them to be loving, patient, humble and peaceable, never seeking vengeance. Their standards are to be heavenly not earthy standards: he condemns impurity, lust, greed, anger, slander, filthy language, lying, and racial divisions. In the same passage, Paul extolled the virtues of compassion, kindness, patience, forgiveness, love, peace, and gratitude (Col 3:1–17; cf. Galatians 5:16-26) Even so they are to be obedient to the authorities, paying their taxes, on the grounds that the magistrate exercises power which can only come from God.

As noted above, the Corinthians were inclined to regard their freedom from law as a licence to do what they liked. Thus, his attitude towards sexual immorality, set against the mores of Greek-influenced society, is particularly direct: "Flee from sexual immorality. All other sins a man commits are outside his body, but he who sins sexually sins against his own body" (1 Cor. 6:18). His attitude towards marriage, in writing to the Corinthians, is to advise his readers not to marry because of the ‘present distress’ but marriage is better than immoral conduct: “it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion"; the alternative, adopted by Paul himself, is celibacy. As for those who are married, even to unbelievers, should not seek to be parted unless the unbelieving partner wishes it (1 Cor 7); their faith sanctifies the unbeliever. In Ephesians he appears to be more positive holding marriage up as a parable of the relationship between Christ and the church. ( Eph 5:21–33. His attitude towards dietary rules manifests the same caution: all is permitted but some actions may seem to ‘weaker brethren’ to be an implicit acceptance of the legitimacy of idol worship – such as eating food that had been used in pagan sacrifice.

He deals with many other questions on which he may have been asked for advice: their relationship with unbelievers; the duty of supporting other needy Christians, how to deal with church members who had fallen into temptation, the need for self-examination and humility, the conduct of family life, the importance of accepting the teaching authority of the leaders of the church.

His teaching has been criticised as being conservative and even quietist. His view of the shortness of the time before the end is thought to have influenced his ethic. That what he says – for instance, about the appropriate attitude towards unbelievers – appears to vary may be the result of his responding to different questioners whose enquiries are unknown to us. Three particular issues, not all of them controversial at the time have assumed great contemporary importance. One is his attitude towards slaves, the second towards women and the third his attitude towards homosexual relations.

The issue of slavery arises because his letter to the slave owning Philemon whose slave Onesimus, Paul sends with his letter. He fails to condemn the practice (as he does also in writing to the Corinthians) but his asking that Philemon should treat him “not as a slave, but instead of a slave, as a most dear brother, especially to me" (Phil 16) may be thought of as a subtle condemnation of slavery.

He certainly treats women differently from men, though not unambiguously; women were created for man, but as woman was made from man, so many is now born of woman. And all things are from God. And elsewhere there is neither male nor female but all are one in Christ. On the other hand, the man is the head of the woman and, in the first letter to Timothy women are forbidden from teaching or exercising authority over men. The ‘headship’ argument has been used as one reason for opposing the ordination of women.

Finally, on the issue of homosexuality, Paul lists a number of actions which are so wicked that they will deprive whoever commits them of their divine inheritance "Neither immoral nor idolaters nor adulterers nor sexual perverts nor thieves, nor the greedy nor drunkards nor revilers, nor robbers will inherit the kingdom of God." (1 Cor. 6:9-10 RSV) Elsewhere he he describes homosexual acts as unnatural , the perpetrators as being 'consumed with passion for one another and as having abandoned the truth about God for a lie.( Rom 1:24-27) (Attempts have been made to contrast the common unequal relationships common in the ancient world (such as pederasty with modern long-term relationships, but this is an argument accepted by only a few churches.)

Alternative views

Most writing on St. Paul comes from the pen (or keyboard) of Christians and thus, as Hyam Maccoby, the Talmudic scholar, has noted, tends to adopt a reverential tone towards his life and teaching. He is one of a number of authors who has argued that not only can we learn little of Christ's life and teaching from his letters but that Paul of Acts and Paul from his own writing are very different people. Some difficulties have been noted in the account of his life. Additionally, the speeches of Paul, as recorded in Acts, have been argued to show a different turn of mind. Paul of Acts is much more interested in factual history, less in theology; ideas such as justification by faith are absent (see Acts 13:16-41; 17:22-31) as are references to the Spirit. On the other hand, there is no references to John the Baptist in the letters, but Paul mentions him several times in Acts.

A further charge by Maccoby is that the Gospels present Jesus as, essentially, a wandering rabbi and that Paul elevates him to the status of Son of God and Messiah, claims which Jesus did not make himself. Geza Vermes, in his book Jesus the Jew advances precisely this argument. Christian scholars, even as long ago as Wilhelm Wrede (1859-1906), have made similar claims: that Jesus did not claim to be the Messiah and the references to the secrecy of his Messiahship lead to this conclusion. The cogency of these arguments depends on how far the four evangelists themselves are to be treated as creative theologians and what processes took place in the editing of the gospels as written. Some differences can be accounted for by the different demands of storytelling and letterwriting. Also, the tone of the gospels differs between themselves. (At the beginning of St. Mark's gospel the expression 'Son of God' is found but it is not in all ancient manuscripts; the view has been expressed that Jesus somehow 'became' the Son of God at his baptism - a doctrine known as adoptionism. In St. John's Gospel, Jesus is called the divine 'Word' who existed before Abraham.) Differences in translation yield different intepretations. The arguments are dense and complex and cannot be rehearsed in detail here. Maccoby, on the other hand, argues that the Gospels and other later Christian documents were written to reflect Paul's views rather than the authentic life and teaching of Jesus.

Maccoby questions Paul's integrity as well:'Scholars', he says,' feel that, however objective their enquiry is supposed to be, ... never say anything to suggest that he may have bent the truth at times, though the evidence is strong enough in various parts of his life-story that he was not above deception when he felt it warranted by circumstances'. This conclusion, at least, is one upon which readers can make their own judgement by reading all of his letters.