Great Moravia

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Ancient History, Classical History and Mythology

|

This article is part of the Czech history series. |

| Samo's realm |

| Great Moravia |

| Middle Ages |

| Czech lands: 1526-1648 |

| Czech lands: 1648-1867 |

| Czech lands: 1867-1918 |

| Czech lands: 1918-1992 |

|

Part of the series on Slovak History |

|

|---|---|

| Samo's Empire | |

| Principality of Nitra | |

| Great Moravia | |

| Kingdom of Hungary | |

| Royal Hungary | |

| History of Czechoslovakia | |

| Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938) | |

| WWII Slovak Republic (1939-1945) | |

| Slovak National Uprising (1944) | |

| Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1960-1990) | |

|

|

|

Great Moravia was a Slavic empire existing in Central Europe between 833 and the early 10th century. Its core territory laid on both sides of the Morava river, in present-day Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Austria.

The Empire was founded when Prince Mojmír I unified by force the neighboring Principality of Nitra with his own Moravian Principality in 833. Unprecedented cultural development resulted from the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius, who came during the reign of Prince Rastislav in 863. The Great Moravian Empire reached its greatest territorial extent under King Svatopluk I (871-894). Weakened by internal struggle and frequent wars with the Frankish Empire, Great Moravia was ultimately overrun by Magyar invaders in the early 10th century and its remnants were later divided between the Kingdom of Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, and the Holy Roman Empire.

Name

The designation "Great Moravia" - "Ἡ Μεγάλη Μοραβία" originally stems from the work De Administrando Imperio written by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos around 950.

The word "Moravia" did not refer only to present-day Moravia, but to a country situated on both sides of the Morava river, whose (currently unknown) capital was also plausibly called Morava. The adjective "Great" nowadays denotes Moravia plus the annexed territories. In De Administrando Imperio, it may have rather meant "distant", because Byzantine texts used to distinguish between two countries of the same name using the attribute "little" for the territory closer to the Byzantine Empire (such as the Morava rivers in Serbia) and "great" for the more distant territory (such as the Morava river between Moravia and Slovakia).

The names of Great Moravia in other languages are Велья Морава in Old Church Slavonic, Veľká Morava in Slovak, Velká Morava in Czech, and Magna Moravia in Latin.

The use of the term (Great) Slovak Empire instead of Great Moravia is promoted by some Slovak authors who try to define it as an early Slovak state. This term has not been adopted by mainstream historians, though it has to be said, that at the break of the 9th century there have not been a great difference in culture and language between the peoples of today's Morava (in the Czech republic) and Slovakia.

History

Foundation

A kind of predecessor of Great Moravia was Samo's Empire, encompassing the territories of Moravia, Slovakia, Lower Austria and probably extending also to Bohemia, Sorbia at the Elbe, and temporarily to Carinthia between 623 and 658. Although this tribal confederation plausibly did not survive its founder, it created favorable conditions for formation of the local Slavic aristocracy.

In the late 8th century, the Morava river basin and western Slovakia, inhabited by the Slavs and situated at the Frankish border, flourished economically. Construction of numerous river valley settlements as well as hill forts indicates that political integration was driven by regional strongmen protected by their armed retinues. The so-called Blatnica-Mikulčice culture, partially inspired by the contemporaneous Western European and Avar art, arose from this economic and political development. In the 790s, the Slavs settled on the middle Danube overthrew the Avar yoke in connection with Charlemagne's campaigns against the Avars. Further centralization of power and progress in creation of state structures of the Slavs living in this region followed.

As a result, two major states emerged: the Moravian Principality originally situated in present-day southeastern Moravia and westernmost Slovakia (with the probable centre in Mikulčice) and the Principality of Nitra, located in present-day western and central Slovakia (with the centre in Nitra). The Moravian Principality was mentioned for the first time in Frankish sources in 822. Its ruler Mojmír I supported Christian missionaries coming from Passau and he also arguably accepted Frankish formal suzerainty. Nitra was ruled by Prince Pribina, who, although probably still a pagan himself, built the first Christian church in Slovakia ( 828). In 833, Mojmír I ousted Pribina from Nitra and the two principalities became united under the same ruler. Excavations revealed that at least two Nitrian castles ( Pobedim and Čingov) were destroyed during the conquest. But Pribina with his family and retinue escaped to the Franks and their king Louis the German granted him the Balaton principality.

After unification

What modern historians and Constantine VII designate as "Great" Moravia arose in 833 from the above mentioned Mojmír's conquest of the Principality of Nitra. In 846, Mojmír I was succeeded by his nephew Rastislav (846-870). Although he was originally chosen by Frankish king Louis the German, the new prince pursued an independent policy. After stopping a Frankish attack in 855, he also sought to weaken influence of Frankish priests preaching in his realm. Rastislav asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send teachers who would interpret the Christianity in the Slavic vernacular. Upon this request, two brothers, Byzantine officials and missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius came in 863. Cyril developed the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language. Texts translated or written by Cyril and Methodius are considered to be the oldest literature in the Slavic languages. Rastislav was also preoccupied with security and administration of his state. Numerous fortified castles built thorough the country are dated to his reign and some of them (e.g. Devín Castle) are mentioned in connection with Rastislav by Frankish chronicles.

During Rastislav's reign, the Principality of Nitra was given to his nephew Svatopluk as an appanage. The rebellious prince allied himself with the Franks and overthrew his uncle in 870. The beginning of Svatopluk I’s reign was turbulent as his former Frankish allies refused to leave the western part of his empire. The young prince was even taken captive by the Franks and the country rallied around Slavomír who led an uprising against the invaders in 871. Released Svatopluk finally took over the command of the insurgents and drove the Franks from Great Moravia. In the subsequent years, he successfully defended independence of his realm from Eastern Francia and subjected many neighboring lands. As the first Great Moravian leader, Svatopluk I (871-894) assumed the title of the king (rex). Under his reign, the Great Moravian Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, when not only Moravia and Slovakia but also present-day northern Hungary, Lower Austria, Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia and southern Poland belonged to the empire. Svatopluk also withstood several attacks of proto-Magyar tribes and Bulgaria.

In 880, the Pope John VIII issued the Bull Industriae Tuae, by which he set up an independent ecclesiastical province in Great Moravia with Archbishop Methodius as its head. He also named the German cleric Wiching the Bishop of Nitra, and Old Church Slavonic was recognized as the fourth liturgical language, besides Latin, Greek and Hebrew.

Decline and fall

After the death of King Svatopluk in 894, his sons Mojmír II (894-906?) and Svatopluk II succeeded him as the King of Great Moravia and the Prince of Nitra respectively. However, they started to quarrel for domination of the whole Empire. Weakened by an internal conflict as well as by constant warfare with Eastern Francia, Great Moravia lost most of its peripheral territories. The proto- Magyar nomadic tribes also took advantage and invaded the Danubian Basin. Both Mojmír II and Svatopluk II probably died in battles with the proto-Magyars between 904 and 907 because their names are not mentioned in written sources after 906.

In three battles (July 4-5 and August 9, 907) near Bratislava, the Magyars routed Bavarian armies. Historians traditionally put this year as the date of breakup of the Great Moravian Empire. However, there are sporadic references to Great Moravia from later years (e.g. 924/925, 942). The fate of northern and western parts of former Great Moravia in the 10th century is thus largely unclear.

The western part of the Great Moravian core territory (present-day Moravia) was annexed by Bohemia after 955. In 999 it was taken over by Poland under Boleslaus I of Poland and returned to Bohemia in 1019. As for the eastern part of the Great Moravian core territory (present-day Slovakia), its southernmost parts were conquered by the Hungarian chieftain Lehel (Lél) around 925 and they fell under domination of the old Magyar dynasty of Arpads after 955. The rest remained under the rule of the local proto-Slovak aristocracy (western Slovakia maybe sharing the fate of Moravia from 955 to 999). In 1000 or 1001, all of Slovakia was taken over by Poland under Boleslaus I, and in 1030 the southern half of Slovakia was again taken over by Hungary. The rest of Slovakia had been progressively integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary from the end of the 11th century until the 14th century). Since the 10th century, the population of this territory has been evolving into the present-day Slovaks.

List of rulers

- Mojmír I (833-846)

- Rastislav (846-870)

- Slavomír (871)

- Svatopluk I (871-894)

- Mojmír II (894-?906)

Territory and people

The territory of Great Moravia included:

- 833-?907: today's Slovakia + current Moravia (ie. southeastern part of the Czech republic) + Lower Austria (territory north of the Danube)+ Hungary (territory north to Budapest and Theiss River, except for western Hungary)

- 874-?: plus a strip of about 100-250km of present-day Poland above Slovak border ( Vistula Basin, Krakow)

- 880-?: plus a strip of about 100-250km of present-day Poland above Czech border ( Silesia)

- 880-896: plus remaining present-day Hungary east of the Danube

- 880/883/884-894: plus the remaining present-day Hungary (up to Vienna)

- 888/890-895: plus Bohemia

- 890-897: plus Lusatia

As for the history of Bohemia - annexed by Great Moravia for five to seven years (from 888/890 to 895) - the crucial year is 895, when the Bohemians broke away from the empire and became vassals of Arnulf of Carinthia. Independent Bohemia, ruled by the dynasty of Přemyslids, began to gradually emerge.

The inhabitants of Great Moravia were designated "Slovene", which is an old Slavic word meaning the "Slavs". The same name was also used by (future) Slovenians and Slavonians at that time. People of Great Moravia are sometimes called "Moravian peoples" by Slavic texts, and "Sclavi" (i.e. the Slavs), "Winidi" (another name for the Slavs), "Moravian Slavs" or "Moravians" by Latin texts. The present-day terms " Slovaks" / "Slovakia" (in Slovak: Slováci / Slovensko) and " Slovenes" / "Slovenia" (in Slovene: Slovenci / Slovenija) arose later from the above "Slovene".

Towns and castles

According to Geographus Bavarus, 30 out of the 41 Great Moravian castles (civitates) were situated on the territory of present-day Slovakia and the remaining 11 in Moravia. These numbers are also corroborated by archaeological evidence. The only castles which are mentioned by name in written texts are Nitra (828), Devín Castle (today in Bratislava) (864), Bratislava (907), and Uzhhorod (in Ukraine) (903). Many other (for example Mikulčice and Staré Město in Moravia; Pobedim, Ducové, Trenčín, and Beckov in the Váh river valley; Svätý Jur near Bratislava; Ostrá skala in Orava; Čingov and Spišské Tomášovce in Spiš; Esztergom in Hungary; Gars-Thunau in Austria) were identified by excavations.

Most Great Moravian castles were rather large hill forts, fortified by wooden palisades, stone walls and in some cases, moats. Most buildings were made of timber, but ecclesiastical and residential parts were made of stone. At least some churches (e.g. in Bratislava) were decorated by frescoes, plausibly painted by Italian masters since the chemical composition of colors was the same as in northern Italy. In Nitra and Mikulčice, several castles and settlements formed a huge fortified urban agglomeration. Other castles (e.g. Ducové) served as regional administrative centers, ruled by a local nobleman. Their form was probably inspired by Carolingian estates called curtis. The largest castles were usually protected by a chain of smaller forts. Forts (e.g. Beckov) also controlled trade routes and provided shelter for peasants in case of a military attack.

Although location of the Great Moravian capital has not been safely identified, the fortified town of Mikulčice with its palace and 12 churches is the most widely accepted candidate. Nitra, the second centre of the Empire, was ruled autonomously by the heir of the dynasty as an appanage. However, it is fair to note that early medieval kings spent a significant part of their lives campaigning and traveling around their realms due to the lack of reliable administrative capacities. It is thus very likely that they also resided from time to time in other important royal estates, such as Devín and Bratislava.

Culture

Due to the lack of written documents, very little is known about the original Slavic religion and mythology. The territory of Great Moravia was originally evangelized by missionaries coming from the Frankish Empire or Byzantine enclaves in Italy and Dalmatia since the early 8th century (and sporadically earlier). The first known Christian church of the Western and Eastern Slavs was built in 828 by Pribina in his capital Nitra. The church, consecrated by Bishop Adalram of Salzburg, was built in a style similar to contemporaneous Bavarian churches, while architecture of two Moravian churches from the early 9th century (in Mikulčice and Modrá) indicates influence of Irish missionaries. The Church organization in Great Moravia was supervised by the Bavarian clergy until the arrival of Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius in 863.

Foundation of the first Slavic bishopric (870), archbishopric (880), and monastery was the politically relevant outcome of the Byzantine mission initially devised by Prince Rastislav to strengthen his early feudal state. It is not known where the Great Moravian archbishop resided (a papal document mentions him as the archbishop of Moravia, Moravia being the name of a town), but there are several references to bishops of Nitra. Big three-nave basilicas unearthed in Mikulčice, Uherské Hradiště, Bratislava, and Nitra were obviously ecclesiastical centers of the country, but their very construction may have predated the Byzantine mission. Nitra and Uherské Hradiště are also sites where monastic buildings have been excavated. A church built at Devín Castle is clearly inspired by Byzantine churches in Macedonia (from where Cyril and Methodius came) and rotundas, particularly popular among Great Moravian nobles, also have their direct predecessors in the Balkans.

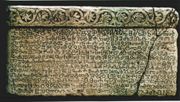

But yields of the mission of Cyril and Methodius extended beyond the religious and political sphere. The Old Church Slavonic became the fourth liturgical language of the Christian world, though its use in Great Moravia proper had gradually declined until it virtually vanished in the late Middle Ages. Its late form still remains the liturgical language of the Russian, Bulgarian, and Serbian Orthodox Church. Cyril also invented the Glagolitic alphabet, suitable for Slavic languages. He translated the Gospel and the first translation of the Bible into a Slavic language was later completed by his brother Methodius.

Methodius wrote the first Slavic legal code, combining the local customary law with the advanced Byzantine law. Similarly, the Great Moravian criminal law code was not merely a translation from Latin, but it also punished a number of offenses originally tolerated by the pre-Christian Slavic moral standards yet prohibited by the Christianity (mostly related to sexual life). The canon law was simply adopted from the Byzantine sources.

There are not many literary works that can be unambiguously identified as originally written in Great Moravia. One of them is Proglas, a cultivated poem in which Cyril defends the Slavic liturgy. Vita Cyrilli (attributed to Clement of Ohrid) and Vita Methodii (written probably by Methodius' successor Gorazd) are biographies with precious information about Great Moravia under Rastislav and Svatopluk I.

The brothers also founded an academy, initially led by Methodius, which produced hundreds of Slavic clerics. A well-educated class was essential for administration of all early-feudal states and Great Moravia was no exception. Vita Methodii mentions bishop of Nitra as Svatopluk I’s chancellor and even Prince Koceľ of the Balaton Principality was said to master the Glagolitic script. Location of the Great Moravian academy has not been identified, but the possible sites include Mikulčice (where some styli have been found in an ecclesiastical building), Devín Castle (with a building identified as a probable school), and Nitra (with its Episcopal basilica and monastery). When Methodius’ disciples were expelled from Great Moravia in 885, they disseminated their knowledge (including the Glagolitic script) to other Slavic countries, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, and Bohemia. They created the Cyrillic alphabet, which became the standard alphabet in the Slavic Orthodox countries, including Russia. The Great Moravian cultural heritage survived in Bulgarian seminaries, paving the way for evangelization of Eastern Europe.

Legacy

Destruction of the Great Moravian Empire was rather gradual. Since excavations of Great Moravian castles show continuity of their settlement and architectural style after the alleged disintegration of the Empire, local political structures must have remained untouched by the disaster. Another reason is that the originally nomad old Magyars lacked siege engines to conquer Great Moravian fortifications. Nevertheless, the core of Great Moravia was finally integrated into the newly established states of Bohemia and the Kingdom of Hungary.

Great Moravian centers (e.g. Bratislava, Nitra, Zemplín) also retained their functions afterwards. As they became the seats of early Hungarian administrative units, the administrative division of Great Moravia was probably just adopted by new rulers. Social differentiation in Great Moravia reached the state of early feudalism, creating the social basis for development of later medieval states in the region. A significant part of the local aristocracy remained more or less undisturbed by the fall of Great Moravia and their descendants became nobles in the newly formed Kingdom of Hungary. Therefore, it is not surprising that many Slavic words related to politics, law, and agriculture were taken into the Hungarian language. The most obvious example of political continuity is the Principality of Nitra, which was ruled autonomously by heirs of the Arpads dynasty – a practice similar to that of the Mojmírs dynasty in Great Moravia. Similarly, the Church organization survived invasion of the pagan Magyars at least to some degree.

Neither the demographic change was dramatic. As far as the graves can tell, there had been no influx of the Magyars into the core of former Great Moravia before 955. Afterwards, Magyar settlers appear in some regions of Southern Slovakia, but graves indicate a kind of cultural symbiosis (resulting in the common Belobrdo culture), not domination. Due to cultural changes, archaeologists are not able to identify the ethnicity of graves after the half of the 11th century (though it is usually possible to determine the ethnicity of a whole village). This is also why integration of central, eastern, and northern Slovakia into the Hungarian Kingdom is difficult to be documented by archeology, and written sources have to be used.

The Byzantine double-cross thought to have been brought by Cyril and Methodius has remained the symbol of Slovakia until today and the Constitution of Slovakia refers to Great Moravia in its preamble. Interest about that period rose as a result of the national revival in the 19th century. Great Moravian history has been regarded as a cultural root of several Slavic nations in Central Europe (especially the Slovaks) and it was employed in vain attempts to create a single Czechoslovak identity in the 20th century.