Trinity

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Divinities

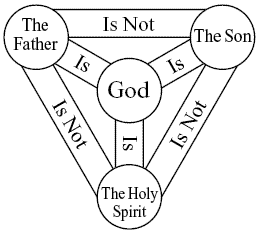

Within Christianity, the doctrine of the Trinity states that God is a single Being who exists, simultaneously and eternally, as a perichoresis of three persons (hypostases, personae): Father (the Source, the Eternal Majesty); the Son (the eternal Logos or Word, incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth); and the Holy Spirit (the Paraclete or advocate). Since the 4th Century, in both Eastern and Western Christianity, this doctrine has been stated as "One God in Three Persons," all three of whom, as distinct and co-eternal "persons" or " hypostases," share a single Divine essence, being, or nature. Supporting the doctrine of the Trinity is known as Trinitarianism, and is opposed to the positions of Binitarianism (two deities/persons/aspects), Unitarianism (one deity/person/aspect), the Godhead (Mormonism) (three separate beings) and Modalism ( Oneness) which are held by some Christian groups.

Scripture and tradition

The word "Trinity" comes from "Trinitas", a Latin abstract noun that most literally means "three-ness" (or "the property of occurring three at once"). Or, simply put, "three are one". The first recorded use of this Latin word was by Tertullian in about 200, to refer to Father, Son and Holy Spirit, or, in general, to any set of three things. ( Theophile of Antioch - 115-181 - introduced the word Trinity in his Book 2, chapter 15 on the creation of the 4th day).

The Greek term used for the Christian Trinity, "Τριάς" (a set of three or the number three), has given the English word triad. The Sanskrit words, "Trimurti or Trinatha," has a similar meaning, as has "Dreifaltigkeit" in German, and many other words in other languages.

The New Testament does not use the word "Τριάς" (Trinity), but only speaks of God (often called "the Father"), of Jesus Christ (often called "the Son"), and of the Holy Spirit, and of the relationships between them. The word "Trinity" began to be applied to them only in the course of later theological reflection.

The earliest Christians were noted for their insistence on the existence of one true God, in contrast to the polytheism of the prevailing culture. While maintaining strict monotheism, they believed also that the man Jesus Christ was at the same time something more than a man (a belief reflected, for instance, in the opening verses of the Letter to the Hebrews, which describe him as the brightness of God's glory and bearing the express image of God's own being, and, yet more explicitly, in the prologue of the Gospel according to John) and also with the implications of the presence and power of God that they believed was among them and that they referred to as the Holy Spirit. The Epistle to the Colossians further states that "in [Jesus] lives all the fullness of Deity bodily" ( Colossians 2:9).

The importance for the first Christians of their faith in God, whom they called Father, in Jesus Christ, whom they saw as the Son of God, the Word of God (Gospel of John), King, Saviour (Martyrdom of Polycarp), Master (First Apology of Justin Martyr), and in the Holy Spirit is expressed in formulas that link all three together, such as those in the Gospel according to Matthew, the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" ( Matthew 28:19); and in the Second Letter of St Paul to the Corinthians: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all" ( 2 Corinthians 13:14).

Conclusions about how best to explain the association of Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit with the one God developed gradually and controversially. Christians had to reconcile their belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ with their belief in the one-ness of God. In doing so, some stressed the one-ness to the point of considering Father, Jesus and Holy Spirit as merely three modes or roles in which God shows himself to mankind; others stressed the three-ness to the point of positing three divine beings, with only one of them supreme and God in the full sense. Only in the fourth century were the distinctness of the three and their unity brought together and expressed in mainline Christianity in a single doctrine of one essence and three persons. Some Christians still debate the differences found in the New Testament, where Christ declared "I and my Father are one," but also prayed on the cross, "Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani" (My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?), which is often explained that first sentence refers to Jesus' divine nature and the second one to his human nature; another explanation is that the prayer on the cross quotes Psalm 22:1 in order to name the entire Psalm, interpreted as prophesying Jesus' crucifixion; most mainstream Christians take the view that the prayer comes from Jesus's anguish at being temporarily separated from the Trinity "mystic oneness" in order that he could take the punishment for sin on behalf of all mankind; and still others (not the mainstream view) say that it is a ridiculous notion that this man is yelling at himself that he is abandoning himself.

In 325, the Council of Nicaea adopted a term for the relationship between the Son and the Father that from then on was seen as the hallmark of orthodoxy; it declared that the Son is "of the same substance" ( ὁμοούσιος) as the Father. This was further developed into the formula "three persons, one substance". The answer to the question "What is God?" indicates the one-ness of the divine nature, while the answer to the question "Who is God?" indicates the three-ness of "Father, Son and Holy Spirit."

The Council of Nicaea was reluctant to adopt language not found in Scripture, and ultimately did so only after Arius showed how all strictly biblical language could also be interpreted to support his belief, that there was a time before Jesus was created when he did not exist. In adopting non-biblical language, the council's intent was to preserve what they thought the Church had always believed that Jesus is fully God, coeternal with God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

Historically, the lack of an explicit scriptural basis for the Trinity was viewed as a disquieting problem, and there is evidence indicating that one mediaeval Latin writer, while purporting to quote from the First Epistle of John, inserted a passage now known as the Comma Johanneum ( 1 John 5:7) which explicitly references the Trinity. It may have begun as a marginal note quoting a homily of Cyprian that was inadvertently taken into the main body of the text by a copyist. The Comma found its way into several later copies, and was eventually back-translated into Greek and included in the third edition of the Textus Receptus which formed the basis of the King James Version. Erasmus, the compiler of the Textus Receptus, noticed that the passage was not found in any of the Greek manuscripts at his disposal and refused to include it until presented with an example containing it, which he rightly suspected was concocted after the fact. Isaac Newton, known mainly for his scientific and mathematical discoveries, noted that many ancient authorities failed to quote the Comma when it would have provided substantial support for their arguments, suggesting it was a later addition. Modern textual criticism has since concurred with his findings; many modern translations now either omit the passage, or make it clear that it is not found in the early manuscripts.

Baptism as the beginning lesson

Many Christians begin to learn about the Trinity through knowledge of Baptism. This is also a starting point for others in comprehending why the doctrine matters to so many Christians, even though the doctrine itself teaches that the being of God is beyond complete comprehension. The Apostles' Creed and the Nicene Creed are structured around profession of the Trinity, and are solemnly professed by converts to Christianity when they receive baptism, and in the Church's liturgy, particularly when celebrating the Eucharist. One or both of these creeds are often used as brief summations of Christian faith by mainstream denominations.

Baptism itself is generally conferred with the Trinitarian formula, "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit" ( Matthew 28:19); and Basil the Great (330–379) declared: "We are bound to be baptized in the terms we have received, and to profess faith in the terms in which we have been baptized." "This is the Faith of our baptism", the First Council of Constantinople declared (382), "that teaches us to believe in the Name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. According to this Faith there is one Godhead, Power, and Being of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit."

Matthew 28:19 may be taken to indicate that baptism was associated with this Trinitarian formula from the earliest decades of the Church's existence. The formula is found in the Didache, Ignatius, Tertullian, Hippolytus, Cyprian, and Gregory Thaumaturgus. Though the formula has early attestation, the Acts of the Apostles only mentions believers being baptized "in the name of Jesus Christ" (2:38, 10:48) and "in the name of the Lord Jesus" (8:16, 19:5). There are no Biblical references to baptism in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit outside Matthew 28:19, nor references to baptism in the name of (the Lord) Jesus (Christ) outside the Acts of the Apostles.

Commenting on Matthew 28:19, Gerhard Kittel states:

- This threefold relation [of Father, Son and Spirit] soon found fixed expression in the triadic formulae in 2 C. 13:13, and in 1 Cor. 12:4-6. The form is first found in the baptismal formula in Mt. 28:19; Did., 7. 1 and 3. . . .[I]t is self-evident that Father, Son and Spirit are here linked in an indissoluble threefold relationship.

In the synoptic Gospels the baptism of Jesus himself is often interpreted as a manifestation of all three Persons of the Trinity: "And when Jesus was baptized, he went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were opened and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him; and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased." ( Matthew 3:16-17, RSV).

Scriptural texts cited as implying support

Many Bible verses imply support for the doctrine that Jesus Christ is God and the closely related concept of the trinity. The Gospel of John in particular supports Jesus' divinity. This is a partial list of supporting Bible verses:

Jesus as God

- John 1:1 "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." together with John 1:14 "The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth." and John 1:18 "No one has ever seen God, but God the One and Only, who is at the Father's side, has made him known."

- John 5:21 "For just as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, even so the Son gives them life to whom he is pleased to give it."

- John 8:23-24: "You are from below; I am from above. You are of this world; I am not of this world. I told you that you would die in your sins; if you do not believe that I am [the one I claim to be], you will indeed die in your sins."

- John 8:58 "'I tell you the truth', Jesus answered, 'before Abraham was born, I am!'"

- John 10:30: "I and the Father are one."

- John 10:38: "But if I do it, even though you do not believe me, believe the miracles, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father."

- John 12:41: "Isaiah said this because he saw Jesus' glory and spoke about him." - As the context shows, this implied the Tetragrammaton in Isaiah 6:1 refers to Jesus.

- John 20:28: “Thomas said to him, 'My Lord and my God!'”

- Phillipians 2:5-6: "Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God,"

- Colossians 2:9: "For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form"

- Titus 2:13: "while we wait for the blessed hope - the glorious appearing of our great God and Saviour, Jesus Christ."

- Hebrews 1:8: "But about the Son he [God] says: "Your throne, O God, will last for ever and ever, and righteousness will be the scepter of your kingdom."

- 1.John 5:20: "We know also that the Son of God has come and has given us understanding, so that we may know him who is true. And we are in him who is true, even in his Son Jesus Christ. He is the true God and eternal life."

- Revelation 1:17-18: "When I saw him, I fell at his feet as though dead. Then he placed his right hand on me and said: "Do not be afraid. I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and behold I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades." This is seen as significant when viewed with Isaiah 44:6: "This is what the LORD says - Israel's King and Redeemer, the LORD Almighty: I am the first and I am the last; apart from me there is no God."

God alone is the Saviour and the Saviour is Jesus

- Jesaja 43:11: I, even I, am the LORD, and apart from me there is no savior.

- Titus 2:10: and not to steal from them, but to show that they can be fully trusted, so that in every way they will make the teaching about God our Savior attractive.

- Titus 3:4: But when the kindness and love of God our Savior appeared

in regard with:

- Luke 2:11: Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is Christ the Lord.

- Titus 2:13: while we wait for the blessed hope, the glorious appearing of our great God and Savior, Jesus Christ

- John 4:42: They said to the woman, "We no longer believe just because of what you said; now we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this man [Jesus] really is the Savior of the world."

- Titus 3:6: whom he poured out on us generously through Jesus Christ our Savior.

Other support for the Trinity

- Matthew 28:19: "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (see Trinitarian formula).

- 1_John 5:7: "For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one." This is the controversial Comma Johanneum, which did not appear in Greek texts before the sixteenth century.

Scriptural texts cited as implying opposition

Among Bible verses cited by opponents of Trinitarianism are those that claim there is only one God, the Father. Other verses state that Jesus Christ was a man. Trinitarians explain these apparent contradictions by reference to the mystery and paradox of the Trinity itself. This is a partial list of verses implying opposition to Trinitarianism:

One God

- Matthew 4:10: "Jesus said to him, 'Away from me, Satan! For it is written: "Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only."'"

- John 17:3: "Now this is eternal life: that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent."

- 1Corinthians 8:5-6: "For even if there are so-called gods, whether in heaven or on earth (as indeed there are many "gods" and many "lords"), yet for us there is but one God, the Father, from whom all things came and for whom we live; and there is but one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things came and through whom we live."

- 1Timothy 2:5: "For there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus"

The Son is subordinate to the Father

- Mark 13:32:"No one knows about that day or hour, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father."

- John 5:19: "Jesus gave them this answer: "I tell you the truth, the Son can do nothing by himself; he can do only what he sees his Father doing, because whatever the Father does the Son also does."

- John 14:28: "You heard me say, 'I am going away and I am coming back to you.' If you loved me, you would be glad that I am going to the Father, for the Father is greater than I."

- John 17:20-23: "My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one: I in them and you in me. May they be brought to complete unity to let the world know that you sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me."

- Colossians 1:15: "He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation."

- 1stCorinthians 15:24-28: "Then the end will come, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. For he "has put everything under his feet." Now when it says that "everything" has been put under him, it is clear that this does not include God himself, who put everything under Christ. When he has done this, then the Son himself will be made subject to him who put everything under him, so that God may be all in all."

Jesus is not the old testament God

- John 2:16: And said unto them that sold doves, Take these things hence; make not my Father's house an house of merchandise.

- Acts 3:13: The God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and of Jacob, the God of our fathers, hath glorified his Son Jesus; whom ye delivered up...

- John 20:17: Jesus saith unto her, Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father: but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and [to] my God, and your God.

- Daniel 7:13: I saw in the night visions, and, behold, [one] like the Son of man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of days, and they brought him near before him.

- Psalms 110:1: Jehovah saith unto my Lord, Sit thou at my right hand, Until I make thine enemies thy footstool.

Ontology of the Trinity

Historical view and usage

The Trinitarian view has been affirmed as an article of faith by the Nicene (325/381) and Athanasian creeds (circa 500), which attempted to standardize belief in the face of disagreements on the subject. These creeds were formulated and ratified by the Church of the third and fourth centuries in reaction to heterodox theologies concerning the Trinity and/or Christ. The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, revised in 381 by the second of these councils, is professed by Orthodox Christianity and, with one addition ( Filioque clause), the Roman Catholic Church, and has been retained in some form by most Protestant denominations.

The Nicene Creed, which is a classic formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity, uses " homoousios" ( Greek: of the same essence) of the relation of the Son's relationship with the Father. This word differs from that used by non-trinitarians of the time, "homoiousios" (Greek: of similar essence), by a single Greek letter, "one iota", a fact proverbially used to speak of deep divisions, especially in theology, expressed by seemingly small verbal differences.

One of the (probably three) Church councils that in 264-266 condemned Paul of Samosata for his Adoptionist theology also condemned the term "homoousios" in the sense he used it, with the result that, as the Catholic Encyclopedia article about him remarks, "The objectors to the Nicene doctrine in the fourth century made copious use of this disapproval of the Nicene word by a famous council."

Moreover, the meanings of "ousia" and " hypostasis" overlapped at the time, so that the latter term for some meant essence and for others person. Athanasius of Alexandria (293-373) helped to clarify the terms.

The terminology of Godhead concerns the nature of God and so is largely distinct from that which concerns specifically the interrelations of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

One God

God is one, and the Godhead a single being: The Hebrew Scriptures lift this one article of faith above others, and surround it with stern warnings against departure from this central issue of faith, and of faithfulness to the covenant God had made with them. "Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD" ( Deuteronomy 6:4) (the Shema), "Thou shalt have no other gods before me" ( Deuteronomy 5:7) and, "Thus saith the LORD the King of Israel and his redeemer the LORD of hosts: I am the first and I am the last; and beside me there is no God." ( Isaiah 44:6). Any formulation of an article of faith which does not insist that God is solitary, that divides worship between God and any other, or that imagines God coming into existence rather than being God eternally, is not capable of directing people toward the knowledge of God, according to the Trinitarian understanding of the Old Testament. The same insistence is found in the New Testament: "...there is none other God but one" ( 1 Corinthians 8:4). The "other gods" warned against are therefore not gods at all, but substitutes for God, and so are, according to St. Paul, simply mythological or are demons.

So, in the Trinitarian view, the common conception which thinks of the Father and Christ as two separate beings is incorrect. The central and crucial affirmation of Christian faith is that there is one savior, God, and one salvation, manifest in Jesus Christ, to which there is access only because of the Holy Spirit. The God of the Old is still the same as the God of the New. In Christianity, it is understood that statements about a solitary god are intended to distinguish the Hebraic understanding from the polytheistic view, which see divine power as shared by several separate beings, beings which can, and do, disagree and have conflicts with each other. The concept of Many comprising One is quite visible in the Gospel of John, chapter 17, verses 20 through 23.

God exists in three persons

This one God however exists in three persons, or in the Greek hypostases. God has but a single divine nature. Chalcedonians — Roman Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants — hold that, in addition, the Second Person of the Trinity — God the Son, Jesus — assumed human nature, so that he has two natures (and hence two wills), and is really and fully both true God and true human. In the Oriental Orthodox theology, the Chalcedonian formulation is rejected in favour of the position that the union of the two natures, though unconfused, births a third nature: redeemed humanity, the new creation.

In the Trinity, the Three are said to be co-equal and co-eternal, one in essence, nature, power, action, and will. However, as laid out in the Athanasian Creed, only the Father is unbegotten and non-proceeding. The Son is begotten from (or "generated by") the Father. The Spirit proceeds from the Father (or from the Father and through the Son — see filioque clause for the distinction).

It has been stated that because God exists in three persons, God has always loved, and there has always existed perfectly harmonious communion between the three persons of the Trinity. One consequence of this teaching is that God could not have created Man in order to have someone to talk to or to love: God "already" enjoyed personal communion; being perfect, He did not create Man because of any lack or inadequacy He had. Another consequence, according to Rev. Thomas Hopko, is that if God were not a trinity, He could not have loved prior to creating other beings on whom to bestow his love. Thus we find God saying in Genesis 1:26, "Let us make man in our image." For Trinitarians, emphasis in Genesis 1:26 is on the plurality in the Deity, and in 1:27 on the unity of the divine Essence. A possible interpretation of Genesis 1:26 is that God's relationships in the Trinity is mirrored in man by the ideal relationship between husband and wife, two persons becoming one flesh, as described in Eve's creation later in the chapter. Some Trinitarian Christians support their position with the Comma Johanneum described above even though it is widely regarded as inauthentic and was not used patristically.

Mutually indwelling

A useful explanation of the relationship of the distinguishable persons of God is called perichoresis, from Greek going around, envelopment (written with a long O, omega - some mistakenly associate it with the Greek word for dance, which however is spelled with a short O, omicron). This concept refers for its basis to John 14-17, where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. At that time, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to the theory of perichoresis, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes." ( Hilary of Poitiers, Concerning the Trinity 3:1).

This co-indwelling may also be helpful in illustrating the Trinitarian conception of salvation. The first doctrinal benefit is that it effectively excludes the idea that God has parts. Trinitarians affirm that God is a simple, not an aggregate, being. God is not parceled out into three portions, as modalists and others contend. The second doctrinal benefit, is that it harmonizes well with the doctrine that the Christian's union with the Son in his humanity brings him into union with one who contains in himself, in St. Paul's words, "all the fullness of deity" and not a part. (See also: Theosis). Perichoresis provides an intuitive figure of what this might mean. The Son, the eternal Word, is from all eternity the dwelling place of God; he is, himself, the "Father's house", just as the Son dwells in the Father and the Spirit; so that, when the Spirit is "given", then it happens as Jesus said, "I will not leave you as orphans; for I will come to you."

Some forms of human union are considered to be not identical but analogous to the Trinitarian concept, as found for example in Jesus' words about marriage. Mark 10:7-8 "For this cause shall a man leave his father and mother, and cleave to his wife; And they twain shall be one flesh: so then they are no more twain, but one flesh." According to the words of Jesus, married persons are in some sense no longer two, but joined into one. Therefore, Orthodox theologians also see the marriage relationship as an image, or "ikon" of the Trinity, relationships of communion in which, in the words of St. Paul, participants are "members one of another." As with marriage, the unity of the church with Christ is similarly considered in some sense analogous to the unity of the Trinity, following the prayer of Jesus to the Father, for the church, that "they may be one, even as we are one". John 17:22

Eternal generation and procession

Trinitarianism affirms that the Son is "begotten" (or "generated") of the Father and that the Spirit "proceeds" from the Father, but the Father is "neither begotten nor proceeds." The argument over whether the Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, or from the Father and the Son, was one of the catalysts of the Great Schism, in this case concerning the Western addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed.

This language is often considered difficult because, if used regarding humans or other created things, it would necessarily imply time and change; when used here, no beginning, change in being, or process within time is intended and is in fact excluded. The Son is generated ("born" or "begotten"), and the Spirit proceeds, eternally. Augustine of Hippo explains, "Thy years are one day, and Thy day is not daily, but today; because Thy today yields not to tomorrow, for neither does it follow yesterday. Thy today is eternity; therefore Thou begat the Co-eternal, to whom Thou saidst, 'This day have I begotten Thee." {Psalm 2:7}

Economic versus Ontological Trinity

- Economic Trinity: This refers to the acts of the triune God with respect to the creation, history, salvation, the formation of the Church, the daily lives of believers, etc. and describes how the Trinity operates within history in terms of the roles or functions performed by each of the Persons of the Trinity - God's relationship with creation.

- Ontological (or immanent) Trinity: This speaks of the interior life of the Trinity "within itself" ( John 1:1-2) - the reciprocal relationships of Father, Son and Spirit to each other.

Or more simply - the ontological Trinity (who God is) and the economic Trinity (what God does). Most Christians believe the economic reflects and reveals the ontological. Catholic theologian Karl Rahner went so far as to say "The 'economic' Trinity is the 'immanent' Trinity, and vice versa."

The members of the trinity are equal ontologically, but not necessarily economically. In other words, the trinity is not symmetrical in terms of function, or in relationship to one another. The roles of each differ both among themselves, and in relationship to creation. Furthermore, the trinity is not symmetrical with regards to origin. The Son is begotten of the Father ( John 3:16). The Spirit proceeds from the Father ( John 15:26). Only the Father is neither begotten nor proceeding (See Athanasian Creed), but is alone "unoriginate" and eternally communicates the Divine Being to the Word, the Son, by "generation" and to the Spirit by "spiration," in that the Spirit "proceeds from the Father" and in the words of some {Eastern} theologians, "rests on the Son" as seen in the baptism of Jesus.

Economical subordination is implied by the genitive of terms like "Father of", "Son of", and "Spirit of". While orthodox Trinitarianism rejects ontological subordination, it affirms that the Father, being the source of all that is, created and uncreated, has a monarchical relation to the Son and the Spirit. Or, in other terms, it is from the Father that the mission of the Breath and Word originate: whatever God does, it is the Father that does it, and always through the Son, by the Spirit. The Father is seen as the "source" or "fountainhead" from which the Son is born and the Spirit proceeds, much as one might observe water bubbling out of a spring without worrying about when it began doing so. However, this language is hemmed in with qualifications so severe that the analogy in view is easily lost, and is a source of perpetual controversy. The main points, however, are that "there is one God because there is one Father" and that, while the Son and Spirit both derive their existence from the Father, the communion between the Three, being a relationship of Divine Love, is such that there is no subordination according to substance. As one transcendent Being, the Three are perfectly united in love, consciousness, will, and operation. Thus, it is possible to speak of the Trinity as a "hierarchy-in-equality."

This concept is considered to be of momentous practical importance to the Christian life because, again, it points to the nature of the Christian's reconciliation with God. The excruciatingly fine distinctions can issue in grand differences of emphasis in worship, teaching, and government, as large as the difference between East and West, which for centuries have been considered practically insurmountable.

Western Theologian Catherine Mowry LaCugna finds common ground with Eastern scholarship through rejecting modern individualist notions of personhood and emphasising the self-communication of God. Following on from Rahner, she says that God is known ontologically only through God's self-revelation in the economy of salvation, and that "Theories about what God is apart from God's self-communication in salvation history remain unverifiable and ultimately untheological." She says faithful Trinitarian theology must be practical and include an understanding of our own personhood in relationship with God and each other - "Living God's life with one another".

Son begotten, not created

Because the Son is begotten, not made, the substance of his person is that of Yahweh, of deity. The creation is brought into being through the Son, but the Son Himself is not part of it except through His incarnation.

The church fathers used a number of analogies to express this thought. St. Irenaeus of Lyons was the final major theologian of the second century. He writes "the Father is God, and the Son is God, for whatever is begotten of God is God."

Extending the analogy, it might be said, similarly, that whatever is generated (procreated) of humans is human. Thus, given that humanity is, in the words of the Bible, "created in the image and likeness of God," an analogy can be drawn between the Divine Essence and human nature, between the Divine Persons and human persons. However, given the fall, this analogy is far from perfect, even though, like the Divine Persons, human persons are characterized by being "loci of relationship." For Trinitarian Christians, this analogy is particularly important with regard to the Church, which St. Paul calls "the body of Christ" and whose members are, because they are "members of Christ," also "members one of another."

However, any attempt to explain the mystery to some extent must break down, and has limited usefulness, being designed, not so much to fully explain the Trinity, but to point to the experience of communion with the Triune God within the Church as the Body of Christ. The difference between those who believe in the Trinity and those who do not, is not an issue of understanding the mystery. Rather, the difference is primarily one of belief concerning the personal identity of Christ. It is a difference in conception of the salvation connected with Christ that drives all reactions, either favorable or unfavorable, to the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. As it is, the doctrine of the Trinity is directly tied up with Christology.

Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Protestant distinctions

The Western (Roman Catholic) tradition is more prone to make positive statements concerning the relationship of persons in the Trinity. It should be noted that explanations of the Trinity are not the same thing as the doctrine itself; nevertheless the Augustinian West is inclined to think in philosophical terms concerning the rationality of God's being, and is prone on this basis to be more open than the East to seek philosophical formulations which make the doctrine more intelligible.

The Christian East, for its part, correlates ecclesiology and Trinitarian doctrine, and seeks to understand the doctrine of the Trinity via the experience of the Church, which it understands to be "an ikon of the Trinity" and therefore, when St. Paul writes concerning Christians that all are "members one of another," Eastern Christians in turn understand this as also applying to the Divine Persons.

For example, one Western explanation is based on deductive assumptions of logical necessity: which hold that God is necessarily a Trinity. On this view, the Son is the Father's perfect conception of his own self. Since existence is among the Father's perfections, his self-conception must also exist. Since the Father is one, there can be but one perfect self-conception: the Son. Thus the Son is begotten, or generated, by the Father in an act of intellectual generation. By contrast, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the perfect love that exists between the Father and the Son: and as in the case of the Son, this love must share the perfection of person. Therefore, as reflected in the filioque clause inserted into the Nicene Creed by the Roman Catholic Church, the Holy Spirit is said to proceed from both the Father "and the Son". (It would also be appropriate according to Western teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son.)

The Eastern Orthodox church holds that the filioque clause, i.e., the added words "and the Son" (in Latin, filioque), constitutes heresy, or at least profound error. One reason for this is that it undermines the personhood of the Holy Spirit; is there not also perfect love between the Father and the Holy Spirit, and if so, would this love not also share the perfection of person? At this rate, there would be an infinite number of persons of the Godhead, unless some persons were subordinate so that their love were less perfect and therefore need not share the perfection of person.

Anglicans have made a commitment in their Lambeth Conference, to provide for the use of the creed without the filioque clause in future revisions of their liturgies, in deference to the issues of Conciliar authority raised by the Orthodox.

Most Protestant groups that use the creed also include the filioque clause. However, the issue is usually not controversial among them because their conception is often less exact than is discussed above (exceptions being the Presbyterian Westminster Confession 2:3, the London Baptist Confession 2:3, and the Lutheran Augsburg Confession 1:1-6, which specifically address those issues). The clause is often understood by Protestants to mean that the Spirit is sent from the Father, by the Son — a conception which is not controversial in either Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. A representative view of Protestant Trinitarian theology is more difficult to provide, given the diverse and decentralized nature of the various Protestant churches.

Historical development

Because Christianity converts cultures from within, the doctrinal formulas as they have developed bear the marks of the ages through which the church has passed. The rhetorical tools of Greek philosophy, especially of Neoplatonism, are evident in the language adopted to explain the church's rejection of Arianism and Adoptionism on one hand (teaching that Christ is inferior to the Father, or even that he was merely human), and Docetism and Sabellianism on the other hand (teaching that Christ was identical to God the Father, or an illusion). Augustine of Hippo has been noted at the forefront of these formulations; and he contributed much to the speculative development of the doctrine of the Trinity as it is known today, in the West; the Cappadocian Fathers ( Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory Nazianzus) are more prominent in the East. The imprint of Augustinianism is found, for example, in the western Athanasian Creed, which, although it bears the name and reproduces the views of the fourth century opponent of Arianism, was probably written much later.

These controversies were for most purposes settled at the Ecumenical councils, whose creeds affirm the doctrine of the Trinity.

According to the Athanasian Creed, each of these three divine Persons is said to be eternal, each almighty, none greater or less than another, each God, and yet together being but one God, So are we forbidden by the Catholic religion to say; There are three Gods or three Lords. — Athanasian Creed, line 20.

Some contemporary theologians including feminists refer to the persons of the Holy Trinity with gender-neutral language, such as "Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer (or Sanctifier)." This is a recent formulation, which seeks to redefine the Trinity in terms of three roles in salvation or relationships with us, not eternal identities or relationships with each other. Since, however, each of the three divine persons participates in the acts of creation, redemption, and sustaining, traditionalist and other Christians reject this formulation as suggesting a new variety of Modalism. Some theologians and liturgists prefer the alternate expansive terminology of "Source, and Word, and Holy Spirit."

Responding to feminist concerns, orthodox theology has noted the following: a) the names "Father" and "Son" are clearly analogical, since all Trinitarians would agree that God has no gender per se (or, encompasses all sex and gender and is beyond all sex and gender); b) that, in translating the Creed, for example, "born" and "begotten" are equally valid translations of the Greek word "gennao," which refers to the eternal generation of the Son by the Father: hence, one may refer to God "the Father who gives birth"; this is further supported by patristic writings which compare and contrast the "birth" of the Divine Word "before all ages" (i.e., eternally) from the Father with His birth in time from the Virgin Mary; c) Using "Son" to refer to the Second Divine Person is most proper only when referring to the Incarnate Word, who is Jesus, a human who is clearly male; d) in Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic, the noun translated "spirit" is grammatically feminine and the images of the Holy Spirit in Scripture are often feminine as well, as with the Spirit "brooding" over the primordial chaos in Genesis 1 and the image of the Holy Spirit as a dove in the New Testament.

Modalists attempted to resolve the mystery of the Trinity by holding that the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost are merely modes, or roles, of God Almighty. This anti-Trinitarian view contends that the three "Persons" are not distinct Persons, but titles which describe how humanity has interacted with or had experiences with God. In the Role of The Father, God is the provider and creator of all. In the mode of The Son, man experiences God in the flesh, as a human, fully man and fully God. God manifests Himself as the Holy Spirit by his actions on Earth and within the lives of Christians. This view is known as Sabellianism, and was rejected as heresy by the Ecumenical Councils although it is still prevalent today among denominations known as "Oneness" and "Apostolic" Pentecostal Christians, the largest of these sects being the United Pentecostal Church. Trinitarianism insists that the Father, Son and Spirit simultaneously exist, each fully the same God.

The doctrine developed into its present form precisely through this kind of confrontation with alternatives; and the process of refinement continues in the same way. Even now, ecumenical dialogue between Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, the Assyrian Church of the East and Trinitarian Protestants, seeks an expression of Trinitarian and Christological doctrine which will overcome the extremely subtle differences that have largely contributed to dividing them into separate communities. The doctrine of the Trinity is therefore symbolic, somewhat paradoxically, of both division and unity.

Dissent from the doctrine

Many Christians believe that the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity is so central to the Christian faith, that to deny it is to reject the Christian faith entirely. However, a number of nontrinitarian groups, both throughout history and today, identify themselves as Christians but reject the doctrine of the Trinity in any form, arguing that theirs was the original pre-Nicean understanding. Some ancient sects, such as the Ebionites, said that Jesus was not a "Son of God", but rather an ordinary man who was a prophet. Many modern groups also teach various nontrinitarian understandings of God. These include Jehovah's Witnesses, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Christadelphians, Christian Scientists, the Unification Church, the Christian Unitarians, Oneness Pentecostals, and Iglesia ni Cristo, among others. These groups differ from one another in their view of God, but all alike reject the doctrine of the Trinity.

Main Points of Dissent

1. The Essential Mystery of the Trinity

Criticism of the doctrine includes the argument that its "mystery" is essentially an inherent irrationality, where the persons of God are claimed to share completely a single divine substance, the "being of God", and yet not partake of each others' identity. It is also pointed out that many polytheistic pre-Christian religions arranged many of their gods in trinities, and that this doctrine may been promoted by Church leaders to make Christendom more acceptable to surrounding cultures.

2. The Lack of Direct Scriptural Support

Critics also argue the doctrine, for a teaching described as fundamental, lacks direct scriptural support, and even some proponents of the doctrine acknowledge such direct or formal support is lacking. The New Catholic Encyclopedia, for example, says, "The doctrine of the Holy Trinity is not taught [explicitly] in the [Old Testament]"[14], "The formulation 'one God in three Persons' was not solidly established [by a council]...prior to the end of the 4th century", and The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia adds, "The doctrine is not explicitly taught in the New Testament"[citation needed]. The question, however, of why such a supposedly central doctrine to the Christian faith would never have been explicitly stated in scripture or taught in detail by Jesus himself was sufficiently important to 16th century historical figures such as Michael Servetus as to lead them to argue the question. The Geneva City Council, in accord with the judgment of the cantons of Zürich, Bern, Basel, and Schaffhausen, condemned Servetus to be burned at the stake for this, and for his opposition to infant baptism.

3. The Divinity of Jesus Christ

For some, debate over the biblical basis of the doctrine tends to revolve chiefly over the question of the deity of Jesus (see Christology). Those who reject the divinity of Jesus argue among other things that Jesus rejected being called so little as good in deference to God (versus "the Father") (Mark 10:18), disavowed omniscience as the Son, "learned obedience" (Hebrews 5:8), and referred to ascending unto "my Father, and to your Father; and to my God, and to your God" (John 20:17). They also dispute that "Elohim" denotes plurality, noting that this name in nearly all circumstances takes a singular verb and arguing that where it seems to suggest plurality, Hebrew grammar still indicates against it. They also point to statements by Jesus such as his declaration that the Father was greater than he or that he was not omniscient, in his statement that of a final day and hour not even he knew, but the Father (Mark 13:32), and to Jesus' being called the firstborn of creation (Colossians 1:15) and 'the beginning of God's creation,' (Revelation 3:14) which argues against his being eternal. In Theological Studies #26 (1965) p.545-73, Does the NT call Jesus God?, Raymond E. Brown wrote that Mark 10:18, Luke 18:19, Matthew 19:17, Mark 15:34, Matthew 27:46, John 20:17, Ephesians 1:17, 2 Corinthians 1:3, 1 Peter 1:3, John 17:3, 1 Corinthians 8:6, Ephesians 4:4-6, 1 Corinthians 12:4-6, 2 Corinthians 13:14, 1 Timothy 2:5, John 14:28, Mark 13:32, Philippians 2:5-10, 1 Corinthians 15:24-28 are "texts that seem to imply that the title God was not used for Jesus" and are "negative evidence which is often somewhat neglected in Catholic treatments of the subject."

Trinitarians, and some non-Trinitarians such as the Modalists who also hold to the divinity of Jesus Christ, claim that these statements are based on the fact that Jesus existed as the Son of God in human flesh. Thus he is both God and man, who became "lower than the angels, for our sake" (Hebrews 2:6-8, Psalm 8:4-6) and who was tempted as humans are tempted, but did not sin (Hebrews 4:14-16). Some Nontrinitarians counter the belief that the Son was limited only during his earthly life (Trinitarians believe, instead, that Christ retains full human nature even after his resurrection), by citing 1 Corinthians 11:3 ("the head of Christ [is] God" [KJV]), written after Jesus had returned to Heaven, thus placing him still in an inferior relation to the Father. Additionally, they refer to Acts 5:31 and Philippians 2:9, indicating that Jesus became exalted after ascension to Heaven, and to Hebrews 9:24, Acts 7:55, 1 Corinthians 15:24, 28, regarding Jesus as a distinct personality in Heaven, all after his ascension.

4. Usage of Non-Biblical Terminology

Christian Unitarians, Restorationists, and others question the doctrine of the Trinity because it relies on non-Biblical terminology. The term "Trinity" is not found in scripture and the number three is never associated with God in any sense other than within the Comma Johanneum. Detractors hold that the only number ascribed to God in the Bible is One and that the Trinity, literally meaning three-in-one, ascribes a threeness to God that is not Biblical.

Several other examples of terms not found in the Bible include multiple “Persons” in relation to God, the terms “God the Son” and “God the Holy Spirit”, and “eternally” begotten. For instance, a basic tenet of Trinitarianism is that God is made up of three distinct Persons (hypostasis). The term hypostasis is used only one time Biblically in reference to God ( Hebrews 1:3), where it states that Jesus is the express image of God's person (hypostasis). The Bible never uses the term in relation to the Holy Spirit or explicitly mentions the Son having a distinct hypostasis from the Father.

Trinitarians maintain that these ideas are implied within scripture and were necessary additions of the Nicene Era to counter the doctrine of Arianism.

5. Lacking of Holy Spirit in Many Trinitarian Scriptural Citations

It is also argued that the vast majority of scriptures that Trinitarians offer in support of their beliefs refer to the Father and to Jesus, but not to the Holy Spirit. This suggests that the concept of the trinity was not well-established in the early Christian community.

6. Not Held by the Monotheistic Religions of Judaism and Islam to be a True Monotheism

The teaching is also pivotal to inter-religious disagreements with two of the other major faiths, Judaism and Islam; the former reject Jesus' divine mission entirely, the latter accepts Jesus as a human prophet just like Muhammad but rejects altogether the deity of Jesus. Many within Judaism and Islam also accuse Christian Trinitarians of practicing polytheism, of believing in three gods rather than just one. Islam holds that because Allah is unique and absolute (the concept of tawhid) the Trinity is impossible and has even been condemned as polytheistic. This is emphasised in the Qur'an which states "He (Allah) does not beget, nor is He begotten, And (there is) none like Him." (Qur'an, 112:1-4)

Alternate views to the Trinity

There have been numerous other views of the relations of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit; the most prominent include:

- Arius believed that the Son was subordinate to the Father, firstborn of all Creation. However, the Son did have Divine status. This view is very close to that of Jehovah's Witnesses.

- Ebionites believed that the Son was subordinate to the Father and nothing more than a special human.

- Marcion believed that there were two Deities, one of Creation / Hebrew Bible and one of the New Testament.

- Modalism states that God has taken numerous forms in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, and that God has manifested Himself in three primary modes in regards to the salvation of mankind. Thus God is Father in creation (God created or begat a Son through the virgin birth), Son in redemption (God manifested Himself into or indwelt the begotten man Christ Jesus for the purpose of His death upon the cross), and Holy Spirit in regeneration (God's indwelling Spirit within the souls of Christian believers). In light of this view, God is not three separate Persons, but rather one God manifesting Himself in multiple ways. It is held by its proponents that this view maintains the strict monotheism found in Judaism and the Old Testament scriptures.

- Swedenborgianism holds that the Trinity exists in One Person, the Lord God Jesus Christ. The Father, the Being or soul of God, was born into the world and put on a body from Mary. Throughout His life, Jesus put away all the merely human desires and tendencies inherited from Mary until He was completely Divine, even as to His flesh. After the resurrection He influences the world through the Holy Spirit, which is His activity. Thus Jesus Christ is the one God; the Father as to His soul, the Son as to His body, and the Holy Spirit as to His activity in the world.

- The Urantia Book teaches that God is the first "Uncaused Cause" who is a personality that is omniscient, omnipresent, transcendent, infinite, eternal and omnipotent, but He is also a person of the Original Trinity - "The Paradise Trinity" who are the "First Source and Center, Second Source and Center, and Third Source and Centre" or otherwise described as "God, The Eternal Son, and The Divine Holy Spirit". These personalities are not to be confused with Jesus who is also one with God, but not one of the Original Personalities of His Original Paradise Trinity. Each one of the Original Holy Trinity is a separate personality, but acting in function as a divine and First Trinity.

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, aka "Mormons," hold that the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost are three separate and distinct individuals ( Covenant 130:22), but can and do act together in perfect unity as a single monotheistic entity (the " Godhead") for the common purpose of saving mankind, Jesus Christ having received divine investiture of authority from Heavenly Father in the pre-existence. The Latter-day Saint doctrine on the Godhead comes directly from the First Vision of the Prophet Joseph Smith ( History:11). They believe this view to be supported by New Testament scriptures, including the circumstances surrounding the baptism of Jesus ( Matthew 3:16-17) and Christ's prayers to God. Christ's statement that He and His Father are "one" is interpeted to mean one in purpose, which purpose they believe the Apostles were also to join (after their resurrection) as Christ prayed in His intercessory prayer: "...that they may be one, as we are."

- Docetism comes from the Greek: δοκηο (doceo), meaning "to seem." This view holds that Jesus only seemed to be human and only appeared to die.

- Adoptionism holds that Jesus was chosen on the event of his baptism to be anointed by the Holy Spirit and became divine upon resurrection.

- Rastafarians accept Haile Selassie I, the former (and last) emperor of Ethiopia, as Jah (the Rasta name for God incarnate, from a shortened form of Jehovah found in Psalms 68:4 in the King James Version of the Bible), and part of the Holy Trinity as the messiah promised to return in the Bible.

- Islam's Holy Book, the Quran, denounces:

- the term "Trinity" ( Sura 4:171)

- a Trinity composed of Father, Son and Mary ( Sura 5:116). Inclusion of Mary in the presumed trinity may have been due to either a quasi-Christian sect known as the Collyridians in Arabia who apparently believed that Mary was divine, or use of the title " Mother of God" to refer to Mary.

Theory of pagan origin and influence

Nontrinitarian Christians have long contended that the doctrine of the Trinity is a prime example of Christian borrowing from pagan sources. According to this view, a simpler idea of God was lost very early in the history of the Church, through accommodation to pagan ideas, and the "incomprehensible" doctrine of the Trinity took its place. As evidence of this process, a comparison is often drawn between the Trinity and notions of a divine triad, found in pagan religions and Hinduism. Hinduism has a triad, i.e., Trimurti.

As far back as Babylonia, the worship of pagan gods grouped in threes, or triads, was common. This influence was also evident in Egypt, Greece, and Rome in the centuries before, during, and after Christ. After the death of the apostles, many nontrinitarians contend that these pagan beliefs began to invade Christianity. (First and second century Christian writings reflect a certain belief that Jesus was one with God the Father, but anti-Trinitarians contend it was at this point that the nature of the oneness evolved from pervasive coexistence to identity.)

Some find a direct link between the doctrine of the Trinity, and the Egyptian theologians of Alexandria, for example. They suggest that Alexandrian theology, with its strong emphasis on the deity of Christ, was an intermediary between the Egyptian religious heritage and Christianity.

The Church is charged with adopting these pagan tenets, invented by the Egyptians and adapted to Christian thinking by means of Greek philosophy. As evidence of this, critics of the doctrine point to the widely acknowledged synthesis of Christianity with platonic philosophy, which is evident in Trinitarian formulas that appeared by the end of the third century. Roman Catholic doctrine became firmly rooted in the soil of Hellenism; and thus an essentially pagan idea was forcibly imposed on the churches beginning with the Constantinian period. At the same time, neo-Platonic trinities, such as that of the One, the Nous and the Soul, are not a trinity of consubstantial equals as in orthodox Christianity.

Nontrinitarians assert that Catholics must have recognized the pagan roots of the trinity, because the allegation of borrowing was raised by some disputants during the time that the Nicene doctrine was being formalized and adopted by the bishops. For example, in the 4th century Catholic Bishop Marcellus of Ancyra's writings, On the Holy Church,9 :

"Now with the heresy of the Ariomaniacs, which has corrupted the Church of God...These then teach three hypostases, just as Valentinus the heresiarch first invented in the book entitled by him 'On the Three Natures'. For he was the first to invent three hypostases and three persons of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and he is discovered to have filched this from Hermes and Plato." (Source: Logan A. Marcellus of Ancyra (Pseudo-Anthimus), 'On the Holy Church': Text, Translation and Commentary. Verses 8-9. Journal of Theological Studies, NS, Volume 51, Pt. 1, April 2000, p.95 ).

Such a late date for a key term of Nicene Christianity, and attributed to a Gnostic, they believe, lends credibility to the charge of pagan borrowing. Marcellus was rejected by the Catholic Church for teaching a form of Sabellianism.

The early apologists, including Justin Martyr, Tertullian and Irenaeus, frequently discussed the parallels and contrasts between Christianity and the pagan and syncretic religions, and answered charges of borrowing from paganism in their apologetical writings.

Christian life and the Blessed Trinity

The singleness of God's being and the multiplicity of the Divine Persons together account for the nature of Christian salvation, and disclose the gift of eternal life. "Through the Son we have access to the Father in one Spirit" ( Ephesians 2:18). Communion with the Father is the goal of the Christian faith and is eternal life. It is given to humans through the Divine union with humanity in Jesus Christ who, although fully God, died for sinners "in the flesh" to accomplish their redemption, and this forgiveness, restoration, and friendship with God is made accessible through the gift to the Church of the Holy Spirit, who, being God, knows the Divine Essence intimately and leads and empowers the Christian to fulfill the will of God. Thus, this doctrine touches on every aspect of the Trinitarian Christian's faith and life; and this explains why it has been so earnestly contended for, throughout Christian history. In fact, while the oldest traditions hold that it is impossible to speculate concerning the being of God (see apophatic theology), yet those same traditions are particularly attentive to Trinitarian formulations, so basic to mere Christian faith is this doctrine considered to be.

Similarities in the 16th-century Jewish Kabbalah

In the late Kabbalistic tradition, originating in the city of Safed in the 16th century, an essential part of representations of the Tree of life or Etz Hayim is a set of three vertical lines of light, each line being headed by Sefirot, or degrees of altruistic quality at the top. These three Sefirot form a spiritual or heavenly triangle, which rules the whole earthly part of the Tree of Life. It is obvious that Sefirot of Kether (Crown), Chochmah (Wisdom) and Binah (Understanding), i.e. Ancient One, Father and Mother, or even Chochmah, Binah and Tiphereth (Glory) as Son also have much similarity with a secret of Trinity. These three lines (sheloshah kavim) are an essential and very deep spiritual secret of Torah (Torath ha-Sod). Priority, importance and secrecy of Trinity and sheloshah kavim (three lines) is obviously similar. According to kabbalah through these mysterious lines—kav smol, kav yamin and kav emtsa'i— Heaven rules the soul's wishes and destiny.

- Classical kabbalah book "Shamati" of Yehuda Ashlag about 23,5 hours of kav

In popular culture

Trinity is the central female character in the Matrix trilogy. Some believe that the three main characters resemble the holy trinity throughout the trilogy. Morpheus as the Father, Neo as the Son, and Trinity as the Holy Spirit. Another view is that Morpheus represents Elijah, or John the Baptist as the one who sought out and recognized that Neo had the dedication to constantly seek truth. It was Morpheus who Baptized Neo and announced to the others that Neo was the One, while Trinity represents the divine female or Jesus’ female counterpart, Mary Magdalene. While none of them are certain of what God is, they are certain that what they previously knew to be the truth, was indeed a lie to keep mankind from discovering the truth that they were being used as energy to fuel their own selfish fantasies while keeping all the Agent Smiths "on the payroll".

In the Valérian comics, The Rage of Hypsis and In Uncertain Times, the Trinity appeared as Harry Quinlan, the character played by Orson Welles in the 1958 film Touch of Evil, (Father); a hippie (Son) and a broken jukebox (Holy Spirit).

The Irish comedian Dave Allen famously satirised the Trinity as Big Daddy (Father), The Kid (Son) and Spook (Holy Spirit).

In the book Angela's Ashes there is a heart warming scene where Frank McCourt, as a child, mistakenly refers to the "Father, the Son, and the Holy Toast."

In the Fritz Lang film Metropolis, the city mayor Joh Fredersen represents the Father and the humble city proletariat as the Holy Spirit. The son of the mayor, Freder Fredersen, represents the Son. The film ends in statement: The intermediator between brain [Father] and hands [Holy Spirit] is Heart (Son).

Also, in Postcolonial Theory, 'The Holy Trinity' is a term coined by Professor Robert J.C. Young, a well-known postcolonial critic currently based at NYU, with regards to the three main postcolonial theorists whose work constitutes much of the debate in this thriving and controversial field of study: Edward Said, Homi K Bhabha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (Young, Robert J.C., Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race London: Routledge, 1994, p.163)