Attack on Pearl Harbour

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: World War II

| Attack on Pearl Harbour | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theatre of World War II | |||||||||

Ships burning in Pearl Harbour after the attack |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Husband Kimmel ( USN), Walter Short ( USA) |

Chuichi Nagumo (IJN), Mitsuo Fuchida ( IJNAS) |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 8 battleships, 8 cruisers, 29 destroyers, 9 submarines, ~50 other ships, ~390 planes |

6 aircraft carriers, 2 battleships, 3 cruisers, 9 destroyers, 8 tankers, 23 fleet submarines, 5 midget submarines, 441 planes |

||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| 2,335 military and 68 civilians killed, 1,143 military and 35 civilians wounded, 4 battleships sunk, 4 battleships damaged, 3 cruisers damaged, 3 destroyers sunk, 2 other ships sunk, 188 planes destroyed, 155 planes damaged |

55 airmen, 9 submariners killed and 1 captured, 29 planes destroyed, 5 midget submarines sunk |

||||||||

| Pacific campaigns 1941-42 |

|---|

| Pearl Harbour – Thailand – Malaya – Wake – Hong Kong – Philippines – Dutch East Indies – New Guinea – Singapore – Australia – Indian Ocean – Doolittle Raid – Solomons – Coral Sea – Midway |

| Pacific Ocean campaign |

|---|

| Pearl Harbour – Wake Island – Doolittle Raid – Midway – Aleutian Islands – Guadalcanal – Solomon Islands – Gilbert and Marshall Islands – Marianas and Palau – Volcano and Ryūkyū Islands |

The Attack on Pearl Harbour was a surprise attack on Pearl Harbour, Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, USA launched by 1st Air Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941 ( Hawaiʻi time). It was aimed at the Pacific Fleet of the United States Navy and its defending Army Air Corps and Marine defensive squadrons as preemptive war intended to neutralize the American forces in the Pacific in an impending World War II. Pearl Harbour, was actually only one of a number of military and naval installations which were attacked, including those on the other side of island.

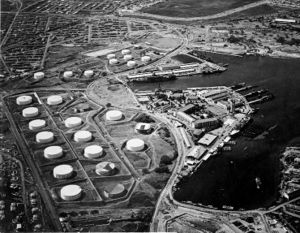

The attack destroyed 8 American battleships, severely damaged 9 other warships, destroyed 188 aircraft, and killed 2,403 American servicemen and 68 civilians. However, the Pacific Fleet's three aircraft carriers were not in port and so were undamaged, as were the base's vital oil tank farms, Navy Yard and machine shops, submarine base, and power station, as well as the Headquarters Building (home to the intelligence unit HYPO). These provided the basis for the Pacific Fleet's campaign during the rest of the War.

Background

After the Meiji Restoration, the Empire of Japan embarked on a period of rapid economic, political, and military expansion in an effort to achieve military, economic, and political parity with the European and North American powers. The expansion strategy included extending territorial and economic control to increase access to natural resources which were thought needed to sustain and accelerate growth.

As a result, Japan embarked on a number of projects which caused confrontations with many other countries. These included the war with China in 1894 in which Japan took control of Taiwan, and the war with Russia in 1904 by which Japan gained territory in and around China and the Korean peninsula. After World War I, the League of Nations awarded Japan custody of most of Imperial Germany's possessions and colonies in the Far East and Pacific waters. In 1931, Japan forcibly imposed a "puppet" state in Manchuria which they called Manchukuo.

From about 1910 through the 1930s Japan had been extensively militarized after considerable internal conflict (eg, assassinations of Opposition leaders) and built a large and modern Navy (third largest in the world at the time) and Army. In 1937, Imperial Army officers staged a provocation at the Marco Polo Bridge, beginning a large-scale invasion of mainland China, involving attacks from Manchuria and several points along China's Pacific coast.

The League of Nations, the U.S., the UK, Australia, and the Netherlands, which had territorial interests in Southeast Asia and the Philippines, disapproved of the Japanese attacks on China, condemning them and applying diplomatic pressure. Japan resigned from the League of Nations in response. In July 1939, the U.S. terminated the 1911 U.S./Japanese commerce treaty, which both showed official disapprobation and removed legal barriers to imposition of trade embargoes. Japan continued its military campaign in China and signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany, formally ending World War I hostilities, and declaring common interests. In 1940, Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Fascist Italy to form the Axis Powers.

These Japanese actions led the U.S. to embargo scrap metal and gasoline, and to close the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. The situation worsened, and in 1941 Japan moved into northern Indochina. The U.S. response was to freeze Japan's assets in the U.S. and to declare a complete oil embargo. Oil was Japan's most crucial resource; her own supplies were very limited, and 80% of Japan's imports came from the U.S. The Imperial Navy relied entirely on imported bunker oil stocks.

There was considerable division in the Japanese high command. The Army wanted to "go south", intending to capture oil and mineral reserves in the Dutch East Indies. The Navy was certain this would bring the U.S. into the war. To forestall American interference, an attack on the Pacific Fleet was considered essential. (The certainty of American aid to Britain in the Pacific is far from clear, and was even at the time.)

Diplomatic negotiations with the U.S. climaxed with the Hull note of November 26, 1941, which Prime Minister Hideki Tojo described to his cabinet as an ultimatum. Japanese leaders felt they had to choose between complying with U.S. and UK demands — backing down from its actions in China and surrounding areas — and continuing expansion. Concerned about losing status and prestige in the international community (" loss of face") if compelled to comply, and with the perceived threat to national survival posed by the Western Powers, the Japanese leadership (under Emperor Hirohito) decided to implement contingency plans, choosing war with the United States, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands as a direct response.

On September 4, 1941, at the second of two Imperial Conferences attended by the Emperor considering an attack on Pearl Harbour, the Japanese Cabinet met to consider the attack plans prepared by Imperial General Headquarters. It was decided that:

Our Empire, for the purpose of self-defence and self-preservation, will complete preparations for war ... [and is] ... resolved to go to war with the United States, Great Britain and the Netherlands if necessary. Our Empire will concurrently take all possible diplomatic measures vis-a-vis the United States and Great Britain, and thereby endeavor to obtain our objectives ... In the event that there is no prospect of our demands being met by the first ten days of October through the diplomatic negotiations mentioned above, we will immediately decide to commence hostilities against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands.

Japanese preparations

Several Navy officers had been impressed with Admiral Andrew Cunningham's Operation Judgement (the Battle of Taranto), where 20 nearly-obsolete Fairey Swordfish, launched from an carrier far from the main British base at Alexandria, disabled half the Italian battle fleet and forced its withdrawal from Mediterranean combat. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto dispatched a naval study delegation to Italy, which concluded a larger and better-supported version of Cunningham's strike could force the U.S. Pacific Fleet to bases in California, allowing time and space for Japan to achieve the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" — shorthand for control of the resources (especially oil reserves) of Southeast Asia (including the Dutch East Indies), with a defensible depth buffer around them. Most importantly, the delegation returned to Japan with information about the shallow running torpedoes Cunningham's "boffins" had devised.

Additionally, some Japanese strategists may have been influenced by U.S. Admiral Harry Yarnell's approach in the 1932 joint Army-Navy exercises, which assumed an invasion of Hawaiʻi. Yarnell, as commander of the attacking force, placed his carriers northwest of Oʻahu in rough weather and launched "attack" planes on the morning of Sunday, February 7, 1932. Umpires noted Yarnell's aircraft were able to inflict serious "damage" on the defenders, who were unable to locate his fleet for 24 hours after the attack. Conventional U.S. Navy doctrine of the time (and other naval opinion as well) believed any attacking force would be destroyed by the battleship force (the "battle line") and dismissed Yarnell's strategy as impractical in the real world.

Yamamoto began considering such an attack early in 1941 as a pre-emptive attack, and assigned Minoru Genda of the IJN to plan it. Genda developed the attack plan which used, and stressed that surprise would be essential given the expected balance of forces; with surprise, he evaluated the attack as "hard, but not impossible." Yamamoto understood Japan was not in a position to fight the U.S and it probable allies. After some pressure on Naval Headquarters (including a threat to resign), he managed to get permission to begin formal planning and training for the proposed attack. The events of the summer (see above) led to preliminary approval of the attack plan at an Imperial Conference (including the Emperor), then approval of the attack in another Conference (also including the Emperor) early in November.

The intent of the attack on Pearl Harbour was to neutralize American naval power in the Pacific, if only temporarily, as part of a theatre-wide, near-simultaneous coordinated attack against several different countries. Yamamoto himself expected even a successful attack would gain (at best) only a year or so of freedom of action before the U.S. recovered enough to check Japan's advances. Preliminary planning for a Pearl Harbor attack in support of military advance elsewhere began in January 1941, and, after some Imperial Navy factional infighting, the project was finally judged worthy. Training for the mission was under way by mid-year. The planned attack depended primarily on torpedoes, but torpedoes of the time required deep water to function when air-launched. This was a critical problem because Pearl Harbour is shallow, except in dredged channels. Over the summer of 1941, Japan secretly created and tested aircraft torpedo modifications allowing successful shallow water drops. The effort resulted in the Type 95 torpedo which inflicted most of the damage to U.S. ships during the attack. Japanese weapons technicians also produced special armor-piercing bombs by fitting fins and release shackles to 14 and 16 inch (356 and 406mm) naval shells. These were able to penetrate the armored decks of battleships and cruisers from 10,000 feet (3000m).

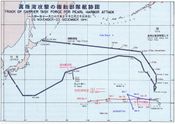

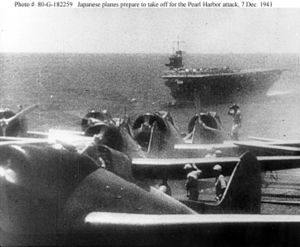

On November 26, 1941, a fleet including six aircraft carriers, two battleships, three cruisers, nine destroyers, eight tankers, 23 fleet submarines, five midget submarines, 441 planes commanded by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo left Hitokappu Bay in the Kuril Islands bound for Hawaiʻi under strict radio silence.

The aircraft carriers were: Akagi, Hiryū, Kaga, Shōkaku, Sōryū, and Zuikaku. Two fast battleships, 2 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 9 destroyers, and 3 fleet submarines provided escort for the task force. The carriers had a total of 423 planes, including Mitsubishi A6M (Type 0) fighters (Allied codename "Zeke", commonly called "Zero"), Nakajima B5N (Type 97) torpedo bombers (Allied codename "Kate"), and Aichi D3A (Type 99) dive bombers (Allied codename "Val"). Japan's task force, and its air group, were larger than any prior aircraft carrier-based strike force. Accompanying the force were eight oilers for refueling. In addition, the Advanced Expeditionary Force included 20 fleet submarines and five two-man Ko-hyoteki-class midget submarines which were to gather intelligence and sink any U.S. vessels that might try to flee Pearl Harbour during or after the attack.

United States preparedness

U.S. civilian and military intelligence forces had, between them, good information suggesting additional Japanese aggression throughout the summer and fall before the attack. None of it specifically indicated an attack against Pearl Harbor. Public press reports during summer and fall, including Hawaiian newspapers, contained extensive reports on the growing tension and on developments in the Pacific. During November, all Pacific commands, including both the Navy and Army in Hawaii, were explicitly warned war with Japan was expected in the very near future, in the Philippines, Indochina, or Russia. The warnings were not specific to any area, noting only that war with Japan was considered likely in the short term and that all commands should act accordingly. Had any of these warnings produced an active alert status, the attack would have been resisted more effectively, and perhaps might have caused less death and damage. Conversely, recall of men to the ships might have led to still more being casualties, and closing watertight doors might have left more trapped in capsized ships. When the attack arrived, Pearl Harbour was unprepared: anti-aircraft weapons were not manned, ammunition was locked down, anti-submarine measures were not implemented (e.g., no submarine nets), combat air patrols not flying, available scouting aircraft not in the air at first light, aircraft parked wingtip to wingtip to lessen sabotage risks, and so on.

U.S. signals intelligence, through the Army's Signal Intelligence Service and the Office of Naval Intelligence's OP-20-G unit, had intercepted and decrypted considerable Japanese diplomatic and naval cipher traffic, though none of those decrypted carried significant tactical military information. Decryption and distribution of this intelligence was capricious and sporadic, and has been blamed on lack of manpower. At best, the information was fragmentary, contradictory, or insufficiently distributed. It was also incompletely understood by decision makers, and poorly unanalyzed. Nothing pointed directly to an attack at Pearl Harbor, and lack of awareness of the Imperial Navy's capabilities led to an underlying belief Pearl Harbour was safely out of harm's way. Only one Hawaiian message (6 December 1941), in a consular cipher, included mention of an attack on Pearl, and it was not decrypted until 8 December 1941. )

In 1924, General Billy Mitchell delivered a 324 page report to his superiors warning of a future war with Japan, possibly including an air-attack on Pearl Harbour; he was essentially ignored. Navy Secretary Knox had also appreciated the possibility in a written analysis shortly after taking office. American commanders had also been warned tests demonstrated shallow-water aerial torpedo launches were possible, but no one in charge in Hawaiʻi fully appreciated that fact. Nevertheless, believing Pearl Harbour had natural defenses against torpedo attack (e.g., the shallow water), the Navy failed to deploy torpedo nets or baffles, which they judged an interference with ordinary operations, and so a low priority. Due to a shortage of long-range aircraft (including Army Air Corps bombers, by a prewar arrangement), reconnaissance patrols were not being made as often as required for adequate coverage. The Navy had only 16 operational PBYs long range aircraft. General Short was low on the priority list for additional B-17s in the Pacific, as General MacArthur in the Philippines was calling for as many as could be made. At the time of the attack, Army and Navy air defence were both on training status rather than on alert. There was confusion about the Army's alert status as Short had changed the designations without keeping higher commands informed. Most of the Army's mobile anti-aircraft guns were secured, with ammunition locked down in separate armories. To avoid upsetting property owners, in keeping with Washington's admonitions not to alarm civil populations (eg, in the late November war warning messages from Navy and War Departments), officers did not keep guns dispersed around the navy base (i.e., on private property). As well, aircraft were parked on airfields to lessen against sabotage risks, not air attack.

Breaking off negotiations

Part of the Japanese plan for the attack included breaking off negotiations with the United States 30 minutes before the attack began. Diplomats from the Japanese Embassy in Washington, including the Japanese Ambassador, Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, and special representative Saburo Kurusu, had been conducting extended talks with the State Department regarding the U.S. reactions to the Japanese move into Indochina in the summer (see above).

In the days before the attack, a long 14-part message was sent to the Embassy from the Foreign Office in Tokyo (encoded with the PURPLE cryptographic machine), with instructions to deliver it to Secretary of State Cordell Hull at 1 p.m. Washington time (In fact, Japan halted all further communication with the U.S. 30 minutes before the attack was scheduled to begin). The last part arrived not long before the attack but, because of decryption and typing delays, and because Tokyo had neglected to inform them of the crucial necessity to deliver it on time, Embassy personnel failed to deliver the message at the specified time. The last part, breaking off negotiations

Obviously it is the intention of the American Government to conspire with Great Britain and other countries to obstruct Japan's efforts toward the establishment of peace through the creation of a new order in East Asia ... Thus, the earnest hope of the Japanese government to adjust Japanese-American relations and to preserve and promote the peace of the Pacific through cooperation with the American Government has finally been lost

was delivered to Secretary Hull several hours after the Pearl Harbour attack.

The United States had decrypted the last part of the final message well before the Japanese Embassy managed to, and long before a fair typed copy of the decrypt was finished. It was decryption of the last part with its instruction for the time of delivery which prompted General George Marshall to send the famous warning message to Hawaii that morning. It was actually delivered, by a young Japanese-American cycle messenger, to Gen. Walter Short at Pearl Harbour several hours after the attack had ended. The delay was due to an inability to locate General Marshall after decryption and translation of the 14th part (he was out for a morning horseride), trouble with the Army's long distance communication system, a decision not to use Navy facilities to transmit it, and various troubles during its travels over commercial cable facilities. Somehow its "urgent" marking was misplaced during its travels and it was delayed by several additional hours.

Japanese records, admitted into evidence during Congressional hearings on the attack after the War, established that the Japanese government had not written any declaration of war until after they heard of the successful attack on Pearl Harbour. That two-line declaration of war was finally delivered to U.S. Ambassador Grew in Tokyo about 10 hours after the attack was over. He was allowed to transmit it to the United States where it was received late Monday afternoon.

The attack

Japanese tactics for attack

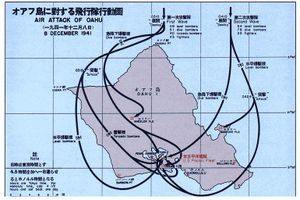

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo decided to implement, and carried out, two waves of air attack. A third attack was suggested by air officers, but Nagumo declined. The first wave of attack consisted of 49 level bombers, 51 dive bombers, 40 torpedo bombers and 43 fighter planes (a total of 183 planes) started from north of Oahu, led by Lieutenant-Commander Mitsuo Fuchida. The second wave consisted of 54 level bombers, 78 dive bombers and 35 fighter planes (a total of 167 airplanes), launched from much the same location. There were also supporting submarines and midget submarines assigned to engage US ships leaving the harbour. The location of the attack force remained unknown to the US until after they had left to return to the Eastern Pacific; they were not located and several searches were made to the south of Oahu. The total planes involved in the aerial attack were 350, and rest of the 91 were engaged in protection of aircraft carriers and other ships during the attack.

The first attack wave was divided into six formations with one directed to Wheeler Field; the second wave was divided into four formations with one formation tasked to Kāneʻohe Marine Corps Base away from Pearl Harbour proper and the rest sent against the main naval base. The separate sections of the attacking aircraft arrived at the attack point almost simultaneously, from several directions. The most vulnerable torpedo bombers made the first attack followed by the dive and level bombers and fighters.

The battle

Even before Nagumo began launching, at 04.30 Hawaiian Time, minesweeper USS Condor spotted a midget submarine outside the Harbour entrance and alerted destroyer Ward. Ward carried out a fruitless search. The first shots fired and the first casualties in the attack on Pearl Harbour occurred when Ward attacked and sank a midget submarine at 06:37. Five Ko-hyoteki-class midgets had been assigned to torpedo U.S. ships after the bombing started. None of these made it back safely, and only four out of the five have since been found. Of the ten sailors aboard the five submarines, nine died; the only survivor, Kazuo Sakamaki, was captured, becoming the first Japanese prisoner of war in World War II. Sakamaki's survival was considered traitorous by the Japanese, who referred to his dead companions as "The Nine Young Gods." United States Naval Institute photographic analysis conducted in 1999 indicates one entered the harbour and successfully fired a torpedo into the West Virginia, in what appears to have been the first shot by the attacking Japanese. The final disposition of this submarine is unknown. The 1st Air Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy attack was coordinated by Lieutenant-Commander Mitsuo Fuchida of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. He flew and led the first strike formation.

On the morning of the attack, the Army's Opana Point station (an SCR-270 radar, located near the northern tip of Oahu), which had not entered official service, having long been in training mode, detected the Japanese planes, but the warning was confused by an untrained new officer (Lieutenant Kermit A. Tyler) at the new and only partially activated Intelligence Centre. Although the operators at Opana Point reported an aircraft sighting larger than anything they had ever seen, the watch officer assumed the pending, scheduled arrival of 6 B-17 bombers was the cause due to the direction from which the aircraft were coming, and because the radar operators had only seen the first element of incoming attackers. In addition, some commercial US shipping may have reported "unusual" radio traffic in the preceding days.

Several U.S. aircraft were shot down as the air attack approached land; one at least radioed a somewhat incoherent warning. Other warnings were still being processed, or awaiting confirmation, when the air raid began. It is not clear that these forewarnings would have had much effect even if they had been interpreted perfectly and much more promptly. The results the Japanese achieved in the Philippines were essentially the same as at Pearl Harbour, though there, MacArthur had nine hours of warning that the Japanese had attacked at Pearl (and specific orders to commence operations).

.

The attack on Pearl Harbour began at 7:53 a.m. December 7 Hawaiian Time; this was 3:23 a.m. December 8 Japanese Standard Time. Japanese planes attacked in two waves; a total of 353 planes reached Oʻahu. Vulnerable torpedo bombers led the first wave of 183 planes, exploiting the first moments of surprise to attack the most important ships (eg, aircraft carriers, battleships, etc), while dive bombers attacked U.S. air bases across Oʻahu, starting with Hickam Field, the largest, and Wheeler Field, the principal fighter base. The 170 planes in the second wave attacked Bellows Field and Ford Island, a Marine and Naval air station in the middle of Pearl Harbour. The only significant air opposition came from a handful of P-36 Hawks and P-40 Warhawks that flew 25 sorties, and from naval anti-aircraft fire.

Men aboard U.S. ships awoke to the sounds of bombs exploding and cries of "Away fire and rescue party" and "All hands on deck, we're being bombed." (The famous message, "Air raid Pearl Harbour. This is not a drill." was issued by Admiral Patrick Bellinger, commanding Navy air patrol squadrons, from his headquarters on Ford Island.) Despite the lack of preparation, which included locked ammunition lockers, aircraft parked wing to wing against sabotage, and a lack of heightened alert status, there were many American military personnel who served with distinction during the battle. Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, and Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh, commander of the Arizona, both rushed to the bridge to direct her defense, until both were killed by an explosion in the forward ammunition magazine, due to an armor piercing bomb hit next to one of the forward main turrets. Both were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honour. Ensign Joe Taussig got his ship, Nevada, under way from a dead cold start during the attack. One of the destroyers got underway with only four officers aboard, all Ensigns, none with more than a year's sea duty. That ship operated for four days at sea before its commanding officer caught up with it. Captain Mervyn Bennion, commanding West Virginia, led his men until he was cut down by fragments from a bomb hit in Tennessee, moored alongside. The earliest aircraft kill credit went to submarine Tautog, which claimed the first attacker downed. Probably the most famous single defender is Doris "Dorie" Miller, an African-American cook aboard West Virginia, who went beyond the call of duty when he took control of an unattended anti-aircraft gun, on which he had no training, and used it to fire on attacking planes, downing at least one, even while bombs were hitting his ship. He was awarded the Navy Cross. In all, 14 sailors and officers were awarded the Medal of Honour. A special military award, the Pearl Harbour Commemorative Medal, was later authorized to all military veterans of the attack.

Ninety minutes after it began, the attack was over. 2,403 Americans died (68 were civilians, many killed by American anti-aircraft shrapnel and shells landing in civilian areas, including Honolulu), a further 1,178 wounded. Eighteen ships were sunk, including five battleships.

Nearly half of the American fatalities — 1,102 men — were caused by the explosion and sinking of Arizona. She was destroyed when a modified 40 cm naval gun shell, dropped from a bomber, smashed through two armored decks and detonated in the forward main magazine. The hull of Arizona has become a memorial to those lost that day, most of whom remain within the ship. It continues to leak small amounts of fuel oil, nearly 70 years after the attack.

Nevada attempted to exit the harbor, but was beached to avoid blocking the harbour entrance. Already damaged by a torpedo and on fire forward, Nevada was targeted by many Japanese bombers as she got underway, sustaining more hits from 250 lb (113 kg) bombs as it beached.

California was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat, but were ordered to abandon ship just as they were raising power for the pumps. Burning oil from Arizona and West Virginia drifted down on her, and probably made the situation look worse than it was. The disarmed target ship Utah was holed twice by torpedoes. West Virginia was hit by seven torpedoes, the seventh tearing away the ship's rudder. Oklahoma was hit by four torpedoes, the last two above her side armor belt which caused it to capsize. Maryland was hit by two of the converted 40 cm shells, but neither caused serious damage.

Although the Japanese concentrated on battleships (the largest vessels present), they did not ignore other targets. The light cruiser Helena was torpedoed, and the concussion from the blast capsized the neighboring minelayer Oglala. Two destroyers in dry dock were destroyed when bombs penetrated their fuel bunkers. The leaking fuel caught fire, flooding the dry dock with water made the oil and fire rise, and that burned out the ships. The light cruiser Raleigh was hit by a torpedo and holed. The light cruiser Honolulu was damaged but remained in service. The destroyer Cassin capsized, and destroyer Downes was heavily damaged. The repair vessel Vestal, moored alongside Arizona, was heavily damaged and beached. The seaplane tender Curtiss was also damaged.

Almost all of the 188 American aircraft in Hawaii were destroyed and 155 of those damaged were hit on the ground, where most had been parked wingtip to wingtip in central positions to minimize sabotage vulnerability. Attacks on barracks killed additional pilots and other personnel. Friendly fire brought down several U.S. planes (including at least one inbound from Enterprise).

Fifty-five Japanese airmen and nine submariners were killed in the action. Of Japan's 441 available planes (350 took part in the attack), 29 were lost during the battle (nine in the first attack wave, 20 in the second), another 74 were damaged by antiaircraft and machine gun fire from the ground. Over 20 of the aircraft that safely landed on their carriers could not be salvaged.

Nagumo's decision to withdraw after two strikes

Some senior officers and flight leaders urged Nagumo to attack with a third strike to destroy the oil storage depots, machine shops, and dry docks at Pearl Harbour. The United States had considered the vulnerability of the fuel oil storage tanks before the war and secretly started construction of the bomb resistant Red Hill fuel tanks before Japan's attack. Destruction of these facilities would have greatly increased the U.S. Navy's difficulties, as the nearest immediately usable fleet facilities would have been several thousand miles east of Hawaiʻi on America's West Coast. Some military historians have suggested that the destruction of oil tanks and repair facilities would have crippled the U.S. Pacific Fleet more seriously than the loss of several battleships. Nagumo decided to forgo a third attack in favour of withdrawing for several reasons:

- Anti-aircraft performance during the second strike was much improved over that during the first, and two-thirds of Japan's losses happened during the second wave, due in part to the Americans being alerted. A third strike could have been expected to suffer still worse losses.

- The first two strikes had essentially used all the previously prepped aircraft available, so a third strike would have taken some time to prepare, perhaps allowing the Americans time to find and attack Nagumo's force. The location of the American carriers was and remained unknown to Nagumo.

- The Japanese pilots had not practiced an attack against the Pearl Harbour shore facilities and organizing such an attack would have taken still more time, though several of the strike leaders urged a third strike anyway.

- The bunker fuel situation did not permit remaining on station north of Pearl Harbour much longer. The Japanese force were acting at the limit of their logistical ability. To remain in those waters for much longer would have risked running unacceptably low on fuel.

- The timing of a third strike would have been such that aircraft would probably have returned to their carriers after dark. Night operations from aircraft carriers were in their infancy in 1941, and neither Japan nor anyone else had developed reliable techniques and doctrine.

- The second strike had essentially completed the entire mission: neutralization of the American Pacific Fleet.

- There was the simple danger of remaining near one place for too long. Japan was very fortunate to have escaped detection during their voyage from the Inland Sea to Hawaiʻi. The longer they remained off Hawaiʻi, the more danger they were in from U.S. submarines and the absent American carriers.

- The carriers were needed to support the main Japanese attack toward the "Southern Resources Area" (i.e., the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, and Burma) which was intended to capture control of oil and other resources. Japanese leaders (especially the Army) had been reluctant to allow the attack at all as it took air cover from the southern thrust, and Nagumo was under strict orders not to risk his command any more than necessary. As the war games during the planning of the attack had predicted that from two to four carriers might be lost in the attack, Nagumo must have been very happy to suffer no losses and very probably did not want to push his luck.

Additional U.S. losses on 7 December 1941

The Japanese submarine I-26 sank the Cynthia Olson, a U.S. Army chartered schooner, off the coast of San Francisco with a loss of 35 lives.

Subsequent attacks

Later during the War several other, small-scale, attacks were also made on Pearl Harbour.

In March, 1942, in Operation K-1, a preparation for the Midway invasion, two Japanese H8K flying-boats, based at Wotje in the Marshall Islands, were tasked with reconnaissance to see how repairs were progressing, and to bomb the important "Ten-ten" repair dock. The distance involved required refueling en route, and was done from submarines at French Frigate Shoals, 500 miles (800 km) north-west of Pearl Harbour. Poor visibility hampered the mission, and the bombs were dropped some miles from their target.

Five Japanese submarines supported the operation: I-9 as a radio beacon; I-19, I-15 and I-26 to refuel the flying boats and I-23 to provide weather reports. However, I-23 was lost without trace.

American ships were posted to the Shoals thereafter, which precluded another attempt using the same approach.

Rumors

During the first days following the attack, rumors began to circulate. One of the most damaging was the claim that Japanese workers had cut arrows into the cane fields, thus pointing the way to Pearl Harbour for the Imperial pilots.

There was no truth to the rumor, and in fact was considered ludicrous by military officers (especially pilots), who knew that any force which could fly hundreds of miles to find O'ahu would have no difficulty finding the largest harbour in the Central Pacific.

However, this rumor was promoted by many who ignored the larger evidence of Japanese navigational skills, preferring to believe that the enemy was inept and would be easily defeated.

Japanese views of the attack

Although the Imperial Japanese government had made some effort to prepare the general Japanese civilian population for war with the U.S. via anti-U.S. propaganda, it appears that most Japanese were surprised, apprehensive, and dismayed by the news that they were now at war with the U.S., a country that many Japanese admired, and its Allies. Nevertheless, the Japanese people living in Japan and its territories thereafter generally accepted their government's account of the attack and supported the war effort until their nation's surrender in 1945, Yamamoto was angry at Nagumo for not launching a third attack and for not destroying the aircraft carriers and the oil supply soon after the attack.

Japan's national leadership at the time appeared to believe that the war between the U.S. and Japan had been inevitable and Japanese-American relationship had already significantly deteriorated since the Japanese conquest of China, which the United States disapproved completely. In 1942, Saburo Kurusu, former Japanese ambassador to the United States, gave an address in which he traced the "historical inevitability of the war of Greater East Asia." He said that the war was a response to Washington's longstanding aggression toward Japan. According to Kurusu, the provocations began with the San Francisco School incident and the United States' racist policies on Japanese immigrants, and culminated in the "belligerent" scrap metal and oil boycott by the United States and Allied countries to contain or reverse the actions of the Empire of Japan whilst expanding its influence and interests throughout Asia. Of Pearl Harbour itself, he said that it came in direct response to a virtual ultimatum from the U.S. government, the Hull note, and that the surprise attack was not treacherous because it should have been expected since Japanese-American relationship already had hit the lowest point and their interests contradicted greatly.

Many Japanese today still feel that they were "pushed" or compelled to fight the U.S. due to threats to their national security and national interests from the U.S. and certain other European powers, and because of embargoes and uncooperation by certain Western powers against the Empire of Japan, particularly United States, United Kingdom and the Netherlands. This embargo was mostly about oil that fueled the whole Imperial Japanese Military operations in its missions. For example, the Japan Times, an English-language newspaper owned by one of the major news organizations in Japan (Asahi Shimbun), ran a number of columns in the early 2000s that echo Kurusu's comments in reference to Pearl Harbour. Putting Pearl Harbour into context, Japanese writers repeatedly contrast the thousands of U.S. servicemen killed in that attack with the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians later killed by U.S. air attacks. not to mention the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States.

However, in spite of the perceived inevitability of the war, many Japanese believe that the Pearl Harbour attack, although a tactical victory, was in reality part of a seriously flawed strategy for engaging in war with the U.S. As one columnist eulogizes the attack:

The Pearl Harbour attack was a brilliant tactic, but part of a strategy based on the belief that a spirit as firm as iron and as beautiful as cherry blossoms could overcome the materially wealthy United States. That strategy was flawed, and Japan's total defeat would follow.

In 1991, the Japanese Foreign Ministry released a statement saying that in 1941 Japan had intended to make a formal declaration of war to the United States at 1 p.m. Washington time, 25 minutes before the attacks at Pearl Harbour were scheduled to begin. This officially acknowledged something which had been publicly known for years, that diplomatic communications had been coordinated well in advance with the attack, and had filed delivery by the intended time.

It appears that the Japanese government was referring to the "14-part message", which did not formally break off negotiations, let alone declare war, but which did in fact officially raise the issue. However, due to various delays, the Japanese ambassador was unable to make the declaration until well after the attack had begun. The Japanese government apologized for this delay. Imperial Japanese military leaders appear to have had mixed feelings about the attack. Yamamoto was unhappy about the botched timing of the breaking off of negotiations. He is rumored to have said, " I fear all we have done is awakened a sleeping giant and filled him with terrible resolve" . Even though this quote is unsubstantiated, the phrase seems to describe his feelings about the attack. He is on record as saying, in the previous year, that "I can run wild for six months ... after that, I have no expectation of success."

The first Prime Minister of Japan during World War II Hideki Tojo later wrote that

When reflecting upon it today, that the Pearl Harbour attack should have succeeded in achieving surprise seems a blessing from Heaven.

Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had stated that, in the impending war with the United States,

Should hostilities once break out between Japan and the United States, it is not enough that we take Guam and the Philippines, nor even Hawaii and San Francisco. We would have to march into Washington and sign the treaty in the White House. I wonder if our politicians (who speak so lightly of a Japanese-American war) have confidence as to the outcome and are prepared to make the necessary sacrifices?"

Longer-term effects

A common view is that the Japan fell victim to victory disease due to the perceived ease of their first victories. Yet despite the perception of this battle as a devastating blow to America, only three ships were permanently lost to the U.S. Navy. These were the battleships Arizona, Oklahoma, and the old battleship Utah (then used as a target ship); nevertheless, much usable material was salvaged from them, including the two aft main turrets from Arizona. Heavy casualties resulted due to Arizona's magazine exploding and the Oklahoma capsizing. Four ships sunk during the attack were later raised and returned to duty, including the battleships California, West Virginia and Nevada. California and West Virginia had an effective torpedo-defense system which held up remarkably well, despite the weight of fire they had to endure, enabling most of their crews to be saved. Many of the surviving battleships were heavily refitted, including the replacement of their outdated secondary battery of anti-surface 5" guns with a more useful battery of turreted DP guns, allowing them to better cope with Japan's threats. The destroyers Cassin and Downes were constructive total losses, but their machinery was salvaged and fitted into new hulls, retaining their original names, while Shaw was raised and returned to service.

Of the 22 Japanese ships that took part in the attack, only one survived the war. As of 2006, the only U.S. ship still afloat that was in Pearl Harbour during the attack is the Coast Guard Cutter Taney.

In the long term, the attack on Pearl Harbour was a strategic blunder for Japan. Indeed, Admiral Yamamoto, who devised the Pearl Harbour attack, had predicted that even a successful attack on the U.S. Fleet could not win a war with the United States, because American productive capacity was too large. One of the main Japanese objectives was to destroy the three American aircraft carriers stationed in the Pacific, but they were not present: Enterprise was returning from Wake Island, Lexington was near Midway Island, and Saratoga was in San Diego following a refit at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Putting most of the U.S. battleships out of commission was regarded—in both Navies and by most observers worldwide—as a tremendous success for Japan.

Though the attack was notable for large-scale destruction, the attack was not significant in terms of long-term loss. Had Japan destroyed the American carriers, the U.S. might have sustained significant damage to its Pacific Fleet for a year or so. As it was, the elimination of the battleships left the U.S. Navy with no choice but to put its faith in aircraft carriers and submarines—and these were the tools with which the U.S. Navy would halt and eventually reverse the Japanese advance. One particular flaw of Japanese strategic thinking was that the ultimate Pacific battle would be between battleships of both sides. As a result, Yamamoto hoarded his battleships for a decisive battle that would never happen.

Ultimately, targets that never made the list, the Submarine Base and the old Headquarters Building, were more important than any of them. It was submarines that brought Japan's economy to a standstill and crippled its transportation of oil, immobilizing heavy ships. And in the basement of the old Headquarters Building was the cryptanalytic unit, Station Hypo.

Historical significance

This battle has had history-altering consequences. It only had a small strategic military effect due to the failure of the Japanese Navy to sink U.S. aircraft carriers, but even if the air carriers had been sunk, it may not have helped Japan in the long term. The attack firmly drew the United States and its massive industrial and service economy into World War II, and the U.S. sent huge numbers of soldiers and a great amount of weapons and supplies to help the Allies fight Germany, Italy, and Japan, contributing to the utter defeat of the Axis powers by 1945. It also resulted in Germany declaring war on the United States four days later.

The United Kingdom's Prime Minister Winston Churchill, on hearing that the attack on Pearl Harbour had finally drawn the United States into the war, wrote: "Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful." The Allied victory in this war and the subsequent U.S. emergence as a dominant world power have shaped international politics ever since.

In terms of military history, the attack on Pearl Harbour marked the emergence of the aircraft carrier as the centre of naval power, replacing the battleship as the keystone of the fleet. However, it was not until later battles, notably the Coral Sea and Midway, that this breakthrough became apparent to the world's naval powers.

Mythical status

Pearl Harbour is a major event in American history marking the first time since the War of 1812 America was attacked on its home soil by another country. The event has assumed mythical status, and its prominence was vividly demonstrated sixty years later when the September 11, 2001 attacks took place: the World Trade Centre and Pentagon attacks were instantly compared to Pearl Harbour.

Cultural impact

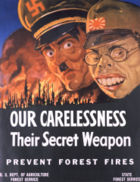

The attack on Pearl Harbour and the ensuing war in the Pacific, fueled anti-Japanese sentiment. Japanese, Japanese-Americans and Asians having a similar physical appearance were regarded with suspicion, distrust and hostility. The attack was viewed as having been conducted in an underhanded way and also as a very "treacherous" or "sneaky attack". The fear of a Japanese-American Fifth column led to a massive detainment of this ethnic population since February 19, 1942 and its resulting Japanese American internment in both the United States and Canada.

The attacks on Pearl Harbour were depicted in the joint American-Japanese film Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), the American film Pearl Harbour (2001) and in several Japanese productions.

Recipients of the Medal of Honour

* Awarded posthumously.

- Mervyn S. Bennion *

- John William Finn

- Francis C. Flaherty *

- Samuel G. Fuqua

- Edwin J. Hill *

- Herbert C. Jones *

- Isaac C. Kidd *

- Jackson C. Pharris

- Thomas J. Reeves *

- Donald K. Ross

- Robert R. Scott *

- Peter Tomich *

- Franklin van Valkenburgh *

- James R. Ward *

- Cassin Young