Western Roman Empire

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Ancient History, Classical History and Mythology; European Geography

|

Division of the Roman Empire |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto: Senatus Populusque Romanus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

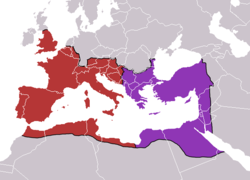

| The Western Roman Empire in 395. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Milan ( 395- 402) Ravenna ( 402- 476) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language(s) | Latin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 395–423 | Honorius | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

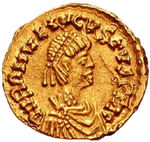

| - 475-476 | Romulus Augustulus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consul | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 395 | Flavius Anicius Hermogenianus Olybrius, Flavius Anicius Probinus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 476 | Basiliscus, Flavius Armatus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Roman Senate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Division of Theodosius | 395 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Deposition of Romulus Augustulus | 476 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 395 | 4,410,000 km2 1,702,711 sq mi |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Solidus, Aureus, Denarius, Sestertius, As | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Western Roman Empire is the western half of the Roman Empire after its division by Diocletian in 286. It existed intermittently in several periods between the 3rd century and the 5th century, after Diocletian's Tetrarchy and the reunifications associated with Constantine the Great, and Julian the Apostate. Theodosius I was the last Roman Emperor who ruled over a unified Roman empire. After his death in 395, the Roman Empire was permanently divided. The Western Roman Empire ended officially with the abdication of Romulus Augustus under pressure of Odoacer on 4 September 476, and unofficially with the death of Julius Nepos in 480.

Despite brief periods of reconquest by its counterpart, the Eastern Roman Empire, widely known as the Byzantine Empire, the Western Roman Empire would not rise again. The Byzantine Empire survived for another millennium before being eventually conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

As the Western Roman Empire fell, a new era began in Western European history: the Middle Ages.

Background

As the Roman Republic expanded, it naturally reached a point in which the central government in Rome could not expect to rule effectively the distant provinces. This was because of slow communications and relatively slow transportation methods. The news of an enemy invasion, a revolt, an epidemic outbreak or of a natural disaster was carried by ship or by mounted postal service (the Cursus publicus) and therefore needed quite some time to reach Rome. A similar amount of time was required for a response and a reaction. Therefore the provinces were administrated by governors who de facto ruled them in the name of the Roman republic.

Shortly before the Roman Empire, the territories of the Roman Republic had been divided between the members of the Second Triumvirate, composed by Octavian, Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.

Antony received all the provinces in the East, namely Achaea, Macedonia and Epirus (roughly modern Greece), Bithynia, Pontus and Asia (roughly modern Turkey), Syria, Cyprus and Cyrenaica. This part had been previously conquered by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC, and a large portion of the local aristocracy were of Greek and Macedonian origin. The majority of the royal dynasties were in fact descendants of his generals. This region had been assimilated to a large degree by the Greek culture, and Greek was the lingua-franca in most of the larger cities.

Octavian, on the other hand, had obtained the Roman provinces of the West: Italia (modern Italy), Gaul (modern France), Gallia Belgica (parts of modern Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg) and Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal). This part also had many Greek and Carthaginian colonies on the coastal areas, but the area had been culturally dominated by the Celtic tribes like the Gauls and the Celtiberians.

Lepidus was given the minor province of Africa (modern Tunisia) to govern. After some political and military developments, Octavian took the province of Africa away from Lepidus and took possession of the Greek-colonized island of Sicilia (modern Sicily).

After the defeat of Mark Antony, the victorious Octavian controlled the whole Roman Empire from Rome. During his reign, his friend Agrippa temporarily ruled over the eastern provinces as his personal representative. This happened again during the rule of Tiberius who sent his heir-apparent Germanicus to the east.

The Roman Empire had many different cultures, and all of them were subject to a gradual process of Romanization. Greek was also spoken in the West and Latin was also spoken the East. Greek culture as a whole was hardly an antagonist to Latin culture, in fact it helped to unify culturally the Roman Empire and both of these cultures were equal partners in the Greco-Roman world. Nevertheless, later military developments with its political consequences divided the Roman Empire, and much later the Byzantine Empire would regroup around Greek culture.

Rebellions, uprisings and political consequences

In peacetime, it was relatively easy to rule the empire from its capital city Rome. An eventual rebellion was expected and would happen from time to time: a general or a governor would gain the loyalty of his officers through a mixture of personal charisma, promises and simple bribes. A conquered tribe would rebel, or a conquered city would revolt. The legions were spread around the borders and the rebel leader would, in normal circumstances, have only one or two legions under his command. Loyal legions would be detached from other points of the empire and would eventually drown the rebellion in blood. This happened even more easily in case of a small local native uprising as the rebels would normally have no great military experience. Unless the emperor was weak, incompetent, hated, and/or universally despised, these rebellions would be local and isolated events.

During real wartime, however, which could develop from a rebellion or an uprising, like the massive Great Jewish Revolt, this was totally and dangerously different. In a full-blown military campaign, the legions under the command of generals like Vespasian were of a much greater number. Therefore to be certain of the commander's loyalty, a paranoid or wise emperor would hold some members of the general's family as hostages. In effect, Nero held Domitian and Quintus Petillius Cerialis the governor of Ostia, who were respectively the younger son and the brother-in-law of Vespasian. The rule of Nero only ended with the revolt of the Praetorian Guard who had been bribed in the name of Galba. The Praetorian Guard was a figurative "sword of Damocles" whose loyalty was bought and who became increasingly greedy. Following their example, the legions at the borders also increasingly participated in the civil wars.

The main enemy in the West was arguably the Germanic tribes behind the rivers Rhine and Danube. Octavian had tried to conquer them but ultimately failed - they were greatly feared.

Parthia, in the East, on the other hand, was too far away to be conquered. Any Parthian invasion was confronted and usually defeated, but the threat itself was ultimately impossible to destroy.

In the case of a Roman civil war these two enemies would seize the opportunity to invade Roman territory in order to raid and plunder. The two respective military frontiers became a matter of major political importance because of the high number of legions stationed there. The local generals would often rebel and start new civil wars. To control the western border from Rome was reasonably easy since it was relatively close. To control both frontiers at the same time during wartime was difficult. If the emperor was near the border in the East, chances were high that an ambitious general would rebel in the West and vice-versa. Emperors were increasingly near the troops in order to control them, and no single emperor could be at the two frontiers at the same time. This problem plagued the ruling emperors, and many future emperors followed this path to power.

Economic stagnation in the West

Rome and the Italian peninsula began to experience an economic slowdown as industries and money began to move outward. By the beginning of the 2nd century AD, the economic stagnation of Italia was seen in the provincial-born Emperors, such as Trajan and Hadrian. Economic problems increased in strength and frequency.

Crisis of the 3rd century

Starting on the 18 March 235, with the assassination of the Emperor Alexander Severus, the Roman Empire fell into a period of fifty years of civil war, known today as the Crisis of the Third Century. The rise of the warlike Sassanid dynasty in Parthia had created a major threat to Rome in the east. Demonstrating the increased danger, Emperor Valerian was captured by Shapur I in 259. His eldest son and heir-apparent, Gallienus, succeeded and was fighting in the eastern frontier. The son of Gallienus, Saloninus, and the Praetorian Prefect Silvanus, were residing in Colonia Agrippina (modern Cologne) trying to maintain the loyalty of the local legions. Nevertheless, the local governor of the German provinces, Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus rebelled and assaulted Colonia Agrippina, killing Saloninus and the prefect. In the confusion that followed an independent state known as the Gallic Empire emerged.

Its capital was Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier), and it quickly expanded its control over the German and Gaulish provinces and over all of Hispania and Britannia. It had its own senate, and a partial list of its consuls still survives. It maintained Roman religion, language, and culture, and was far more concerned with fighting the Germanic tribes than other Romans. However, in the reign of Claudius Gothicus (268 to 270), large expanses of the Gallic Empire were returned to Roman rule.

At roughly the same time, the eastern provinces seceded as the Empire of Palmyra, under the rule of Queen Zenobia.

In 272, Emperor Aurelian finally managed to subdue Palmyra and reclaim its territory for the empire. With the East secure, he turned his attention to the West, and in the next year, the Gallic Empire also fell. Because of a secret deal between Aurelian and the Gallic Emperor Tetricus I and his son Tetricus II, the Gallic army was swiftly defeated. In exchange, Aurelian spared their lives and gave the two former rebels important positions in Italy.

Tetrarchy

The external borders were mostly quiet for the remainder of the Crisis of the Third Century, although between the death of Aurelian in 275 and the accession of Diocletian ten years later, at least eight emperors or would-be emperors were killed, many assassinated by their own troops.

Under Diocletian, the political division of the Roman Empire began. In 286, through the creation of the Tetrarchy, he gave the western part to Maximian as Augustus and named Constantius Chlorus as his subordinate ( Caesar). This system effectively divided the empire into four parts and created separate capitals besides Rome as a way to avoid the civil unrest that had marked the 3rd century. In the West, the capitals were Maximian's Milan and Constantius' Trier. On 1 May 305, the two senior Augusti stepped down and were replaced by their respective Caesars.

Constantine

The system of the Tetrarchy quickly ran aground when the Western Empire's Constantius died unexpectedly in 306, and his son Constantine was proclaimed Augustus of the West by the legions in Britain. A crisis followed as several claimants attempted to rule the Western half. In 308, the Augustus of the East, Galerius, arranged a conference at Carnuntum which revived the Tetrarchy by dividing the West between Constantine and a newcomer named Licinius. Constantine was far more interested in reconquering the whole empire. Through a series of battles in the East and the West, Licinius and Constantine stabilized their respective parts of the Roman Empire by 314, and they now competed for sole control of a reunified state. Constantine emerged victorious in 324 after the surrender and the murder of Licinius following the Battle of Chrysopolis.

The Tetrarchy was dead, but the idea of dividing the Roman Empire between two emperors had been proven too good to be simply ignored and forgotten. Very strong emperors would reunite it under their single rule, but with their death the Roman Empire would be divided again and again between the East and the West.

Second division

The Roman Empire was under the rule of a single Emperor, but with the death of Constantine in 337, civil war erupted among his three sons, dividing the empire into three parts. The West was reunified in 340, and a complete reunification of the whole empire occurred in 353, with Constantius II.

Constantius II focused most of his power in the East, and is often regarded as the first emperor of the Byzantine Empire. Under his rule, the city of Byzantium, only recently refounded as Constantinople, was fully developed as a capital.

In 361, Constantius II became ill and died, and Constantius Chlorus' grandson Julian, who had served as Constantius II's Caesar, took power. Julian was killed carrying on Constantius II's war against Persia in 363 and was replaced by Jovian who ruled only until 364.

Final division

Following the death of Jovian, the empire fell again into a new period of civil war similar to the Crisis of the Third Century. In 364 Valentinian I emerged. He immediately divided the empire once again, giving the eastern half to his brother Valens. Stability was not achieved for long in either half as the conflicts with outside forces intensified, especially with the Huns and the Goths. A serious problem in the West was a political reaction caused by the indigenous paganism against the Christianizing emperors. In 379 Valentinian I's son and successor Gratian declined to wear the mantle of pontifex maximus, and in 382 he rescinded the rights of pagan priests and removed the pagan altar from the Roman Curia, and gave the title of Pontifex Maximus to the Pope.

In 388, a powerful and popular general named Magnus Maximus seized power in the west and forced Gratian's son Valentinian II to flee to the east and ask for the aid of the Eastern Emperor Theodosius I who quickly restored him to power. He also caused a ban on the native paganism to be implemented in the west in 391, enforcing Christianity. In 392 the Frankish and pagan magister militum Arbogast assassinated Valentinian II, and a senator named Eugenius was proclaimed emperor until he was defeated in 394 by Theodosius I, who, having ruled both East and West for a year, died in 395. This was the last time in which a single ruler ruled over both parts of the Roman Empire.

A short period of stability under Emperor Flavius Augustus Honorius (controlled by Flavius Stilicho) ended at Stilicho's death in 408. After this, the two empires truly diverged, as the East began a slow recovery and consolidation, while the West began to collapse entirely.

Economic factors

While the West was experiencing an economic decline throughout the late empire, the East was not so economically decadent, especially as Emperors like Constantine the Great and Constantius II began pouring vast sums of money into the eastern economy. The economic decline of the West aided in the eventual collapse of this area of the empire. Without sufficient taxes, the state could not maintain an expensive professional army and resorted to hiring mercenaries.

As the central power weakened, the State also lost control of its borders and provinces and the vital control over the Mediterranean Sea. Roman Emperors tried to keep outside forces away from controlling sections of the sea, but once the Vandals conquered North Africa, the imperial authorities had to cover too much ground with too few resources. The Roman institutions collapsed along with the economic stability. Most invaders required a third of the land they conquered from their Roman subjects, and this could turn into much more, as different tribes conquered the same province.

Tens of square kilometres of carefully developed land was abandoned due to lack of economic viability and of political stability. Because most of the economy of Classical antiquity was based upon agriculture, this was a severe economic blow. This occurred because most plots of land require a certain investment of time and money in simple maintenance to maintain production. Unfortunately, this meant that any attempt to recover the West by the East was very difficult, and the huge decline in the local economy made these new reconquests too expensive to maintain.

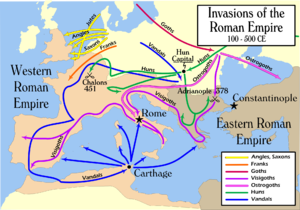

Conquest of Rome and fall of the Western Roman Empire

With the death of Stilicho in 408, Honorius was left in charge, and although he ruled until his death in 423, his reign was filled with usurpations and invasions, particularly by the Vandals and Visigoths. In 410, Rome was sacked by outside forces for the first time since the Gallic invasions of the 4th century BC. The instability caused by usurpers throughout the Western Empire helped these tribes in their conquests, and in the 5th century the Germanic tribes became usurpers themselves. In 475, Orestes, a former secretary of Attila the Hun drove Emperor Julius Nepos out of Ravenna and proclaimed his own son Romulus Augustus as emperor.

Although some isolated pockets of Roman rule continued (in Dalmatia under emperor Julius Nepos and north-western Gaul under Syagrius ), the control of Rome over the West had effectively ended. In 476, Orestes refused to grant the Heruli led by Odoacer federated status, and Odoacer sacked Rome and sent the imperial insignia to Constantinople, installing himself as king over Italy.

Last emperor

Historical convention has determined that the Western Roman Empire ended on 4 September 476, when Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus. However, the issue in practice is not clear-cut.

Julius Nepos still claimed to be Emperor of the West, ruling the rump state of Dalmatia, and was recognized as such by Byzantine Emperor Zeno and by Syagrius, who had managed to preserve a Roman enclave in northern Gaul, known today as the Domain of Soissons. Odoacer proclaimed himself ruler of Italy and began to negotiate with Zeno. The Byzantine emperor eventually did grant Odoacer patrician status as a recognition of his authority and accepted him as his own viceroy of Italy. Zeno however insisted that Odoacer payed homage to Nepos as western emperor. Odoacer accepted this condition and even issued coins in Nepos' name throughout Italy. This however was mainly an empty political gesture as Odoacer never returned any real power or territories to Nepos. Nepos was eventually murdered in 480 and Odoacer quickly invaded and conquered Dalmatia.

Theodoric

The last hope for a reunited Empire came in 493, as Odoacer was replaced by the Ostrogoth Theodoric the Great. Theodoric had been recruited by Zeno to reconquer the western portion of the empire, Rome most importantly. De jure he was a subordinate, a viceroy of the emperor of the East. De facto Theodoric was an equal.

Following Theodoric's death in 526, the West no longer resembled the East. The West was now fully controlled by invading outside tribes, while the East had retreated and Hellenized. While the East would make some attempts to recapture the West, it was never again the old Roman Empire.

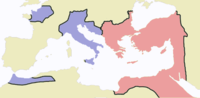

Byzantine reconquest

Throughout the Middle Ages, the eastern Byzantine Empire laid claims on areas of the West which had been occupied by several tribes. In the 6th century, the Byzantine Empire managed to reconquer large areas of the former Western Roman Empire. The most successful were the campaigns of the Byzantine generals Belisarius and Narses on behalf of Emperor Justinian I from 533 to 554. The Vandal-occupied former Roman territory in North Africa was regained, particularly the territory centred around the city of Carthage. The campaign eventually moved into Italy and reconquered it completely. Minor territories were taken as far west as the southern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.

It appeared at the time that perhaps Rome could be reconstituted. However, the tribal influence had caused far too much damage to these former Roman provinces, both economically and culturally. Not only were they extremely costly to maintain, the invasion and propagation of the Germanic tribes throughout these territories meant that much of the Roman culture and identity that had held the empire together had been destroyed or severely damaged.

Although some eastern emperors occasionally attempted to reconquer some parts of the West, none were as successful as Justinian. The division between the two areas grew, resulting in a growing rivalry. While the Eastern Roman Empire continued after Justinian, the eastern emperors focused mainly on defending its traditional territory. The East no longer had the necessary military strength, spelling the end of any hope for reunification.

Legacy

As the Western Roman Empire crumbled, the new Germanic rulers who had conquered the provinces felt the need to uphold many Roman laws and traditions as they felt appropriate. Many of the invading Germanic tribes were already Christianised, but most of them were followers of Arianism. They quickly converted to the Catholic faith, gaining more loyalty by the local Romanized population and at the same time recognition and support by the powerful Roman Catholic Church. Although they initially continued to recognise their indigenous tribal laws, they were more influenced by Roman Law and gradually incorporated it as well.

Roman Law, particularly the Corpus Juris Civilis collected by order of Justinian I, is the ancient basis on which the modern Civil law stands. In contrast, Common law is based on the Germanic Anglo-Saxon law.

Latin as a language never really disappeared. It combined with neighboring Germanic and Celtic languages, giving origin to many modern Romance languages such as: Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian and Romansh, and influenced many Germanic languages such as English, German, Dutch and many others to a certain extent. It survives in its "purer" form as the language of the Roman Catholic Church (the Mass was spoken exclusively in Latin until 1965) and was used as a lingua franca between many nations. It remained the language of medicine, law, diplomacy (most treaties were written in Latin), of intellectuals and scholarship.

The Latin alphabet was expanded with the letters J, K, W and Z and is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world today. Roman numerals continue to be used but were mostly replaced by Arabic numerals.

The ideal of the Roman Empire as a mighty Christian Empire with a single ruler continued to seduce many powerful rulers. Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Lombards, was even crowned as Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800. Emperors of the Holy Roman Empire like Frederick I Barbarossa, Frederick II and Charles V, and mighty Sultans like Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire, among others, tried to a certain extent to resurrect it, but none of their attempts were successful.

A very visible legacy of the Western Roman Empire is the Roman Catholic Church. The Church slowly began to replace Roman institutions in the West, even helping to negotiate the safety of Rome during the late 5th Century. As Rome was invaded by Germanic tribes, many assimilated, and by the middle of the medieval period (c.9th and 10th centuries) the central, western and northern parts of Europe had been largely converted to the Roman Catholic Faith and acknowledged the Pope as the Vicar of Christ.

List of Western Roman emperors

Gallic Emperors (259 to 273)

- Postumus: 259 to 268

- Laelianus: 268 Usurper

- Marcus Aurelius Marius: 268

- Victorinus: 268 to 271

- Domitianus: 271 Usurper

- Tetricus I: 271 to 273

- Tetricus II: 271 to 273 Son and co-emperor of Tetricus I

Tetrarchy (293 to 313)

Augusti are shown with their Caesares and regents further indented

- Maximian: 293 to 305

- Constantius Chlorus: 293 to 305

- Constantius Chlorus: 305 to 306

- Flavius Valerius Severus: 305 to 306

- Flavius Valerius Severus: 306 to 307

- Constantine I: 306 to 313

- Maxentius/ Maximian: 307 to 308

- Licinius: 308 to 313

- Maxentius: 308 to 312 Usurper

- Domitius Alexander: 308 to 309 African usurper

Constantinian dynasty (313 to 363)

- Constantine I: 313 to 337 Sole emperor of the whole Roman Empire 324 to 337

- Constantine II: 337 to 340 Emperor of Gaul, Britannia, and Hispania

- Constans I: 337 to 350 Initially emperor of Italy and Africa; emperor of the west 340 to 350

- Magnentius: 350 to 353 Usurper

- Constantius II: 353 to 361 Sole emperor

- Julian: 355 to 361

- Julian: 361 to 363

Non-dynastic (363 to 364)

- Jovian: 363 to 364

Valentinian dynasty (364 to 392)

- Valentinian I: 364 to 375

- Gratian: 367 to 375

- Gratian: 375 to 383

- Valentinian II: 375 to 383

- Magnus Maximus: 383 to 388 Usurper

- Valentinian II: 383 to 392

Non-dynastic (392 to 394)

- Eugenius: 392 to 394

Theodosian dynasty (394 to 455)

- Theodosius I: 394 to 395 Sole emperor

- Honorius: 395 to 423

- Flavius Stilicho: 395 to 408 Power behind the throne

- Constantius III: 421

- Constantine III: 407 to 411 Usurper

- Priscus Attalus: 409 to 410/414 to 415 Usurper

- Jovinus: 411 to 412 Usurper

- Valentinian III: 423 to 455

- Galla Placidia: 423 to 433 Regent

- Aëtius: 433 to 454 Regent

- Joannes: 423 to 425 Usurper

Non-dynastic (455 to 480)

- Petronius Maximus: 455

- Avitus: 455 to 456

- Ricimer: 456 to 472 Power behind the throne

- Majorian: 457 to 461

- Libius Severus: 461 to 465

- Anthemius: 465 to 472

- Olybrius: 472

- Glycerius: 473 to 474

- Julius Nepos: 474 to 480 In exile 475 to 480

- Romulus Augustus: 475 to 476

- Flavius Orestes: 475 to 476 Power behind the throne

Flavius Orestes was killed by revolting Germanic mercenaries. Their chieftain, Odoacer, assumed control of Italy as a de jure representative of Julius Nepos and Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno.