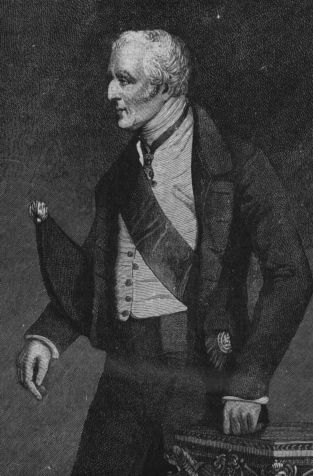

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1750-1900; Military People

| The Duke of Wellington | |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 22 January 1828 – 16 November 1830 17 November 1834 – 9 December 1834 |

|

| Preceded by | The Viscount Goderich The Viscount Melbourne |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Grey Sir Robert Peel, Bt |

|

|

|

| Born | c. 1 May 1769 Possibly Dublin or County Meath |

| Died | 14 September 1852 Walmer, Kent |

| Political party | Tory |

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS ( c. 1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Irish-born British soldier and statesman, widely considered one of the leading military and political figures of the 19th century. Commissioned an ensign in the British Army, he rose to prominence in the Napoleonic Wars, eventually reaching the rank of field marshal.

As a general Wellington is often compared to the 1st Duke of Marlborough, with whom he shared many characteristics, chiefly a transition to politics after a highly successful military career. He served as a Tory Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on two separate occasions, and was one of the leading figures in the House of Lords until his retirement in 1846.

Early life and marriage

Wellington was born The Honourable Arthur Wesley at either his family's social season Dublin residence, Mornington House, or at his family seat, Dangan Castle near Trim, County Meath, Ireland. He was the third son of Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington. His exact date of birth is uncertain. All that exists is a church register of the event marked a few days after it must have occurred. The most likely date is 1 May 1769. His family legally changed their surname to Wellesley in March 1798.

He came from a titled family long settled in Ireland. His father was the Earl of Mornington, his eldest brother (who inherited his father's earldom) became Marquess Wellesley, and two of his other brothers were raised to the peerage as Baron Maryborough and Baron Cowley.

As a member of the Protestant British squirearchy ruling Ireland, he was touchy about his Irish origins. When in later life an enthusiastic Gael commended him as a famous Irishman, he replied "A man can be born in a stable, and yet not be an animal."

Wesley was educated at Eton from 1781 to 1785, but a lack of success there, combined with a shortage of family funds, led to a move to Brussels in Belgium to receive further education.

Until his early twenties, Wesley showed no signs of distinction. His mother placed him in the army, saying "What can I do with my Arthur?" He became a nobleman playboy, carousing and gambling. He fell in love with the daughter of a fellow Anglo-Irish peer, Miss Kitty Pakenham, and proposed marriage, but was rejected by her family for having no prospects. It seems likely that, at least in part, the shock of rejection caused him to reform all his bad habits: he minimized his drinking, stopped gambling and even burned his beloved fiddle. He also began a rigid course of self-education in military science, something that would be taught by no professional academy for another decade. He volunteered for service in the Netherlands and India, and achieved spectacular success, rising in a decade to the rank of general, never losing a battle, and winning prize money from grateful rajahs. On returning to Ireland he immediately renewed his marriage proposal to Miss Pakenham, before even meeting her again, and possibly without even having corresponded with her for ten years. This time her family accepted him, but he seems to have quickly regretted his decision on seeing how Kitty had grown old in his absence. However a promise was a promise; their marriage lasted the rest of her life, producing two sons but a great deal of loveless anguish.

Early career

In 1787 his mother and his brother Richard purchased for Wesley a commission as an ensign in the 73rd Regiment of Foot. After receiving military training in England he attended the Military Academy of Angers in France. His first assignment was as aide-de-camp to two successive Lords Lieutenant of Ireland (1787–1793). He was promoted to lieutenant in 1788. Two years later he was elected as an independent member of Parliament for Trim in the Irish House of Commons, a position he held for seven years. He gained rapid promotion (largely by purchasing his ranks, which was common in the British Army at the time), becoming lieutenant colonel in the 33rd Regiment of Foot in 1793. He participated in the unsuccessful campaign against the French in the Netherlands between 1794 and 1795, and was present at the Battle of Boxtel.

In 1796, after a promotion to colonel, he accompanied his division to India. The next year his elder brother Richard was appointed Governor-General of India, and when the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War broke out from 1798 against the Sultan of Mysore, Tipoo Sultan, Arthur Wellesley commanded a division of his own. While serving in that capacity, he was appointed Governor of Seringapatam and of Mysore, positions he held until 1805. He defeated the robber chieftain Dhundia Wagh (who had escaped from prison in Seringapatam during the last battle of the Mysore War). In the Maratha War of 1803, Wellesley commanded the outnumbered British army at Assaye and Argaum, and stormed the fortress at Gawilghur. On one occasion he outran the Mysore soldiers pursuing him and avoided being killed. Through his own skill as a commander, and the bravery of his British and Sepoy troops, the Indians were defeated at every engagement. Following the successful conclusion of that campaign he was appointed to the supreme military and political command in the Deccan. In 1804 he was created a Knight of the Bath, the first of numerous honours he received throughout his life. When his brother's term as Governor-General of India ended in 1805, the brothers returned together to England, where they were forced to defend their imperialistic (and expensive) employment of the British forces in India. India taught him to abandon the then-common British habit of infrequent bathing. Lord Wellington is usually credited with popularizing the custom of daily bathing in his own country.

Wellesley served in the abortive Anglo-Russian expedition to north Germany in 1805. After Austerlitz, the forces went home having accomplished nothing. He was elected Tory member of Parliament for Rye for six months in 1806. A year later he was elected MP for Newport on the Isle of Wight, a constituency he would represent for two years. In April 1807 he became a privy counsellor. He served as Chief Secretary for Ireland for two years. However his political life came to an abrupt halt when he sailed to Europe to participate in the Napoleonic Wars.

Napoleonic Wars

It was in the following years that Wellesley won his place in history. Since 1789, France had been embroiled in the French Revolution, and after seizing the government in 1799, Napoleon had reached the heights of power in Europe.

Junior command in an expedition to Denmark in 1807 soon led to Wellesley's promotion to lieutenant general. In 1808 he was preparing to command an expedition to Venezuela, when the Spanish revolt in the Iberian peninsula began the Peninsular War. Wellesley defeated the French at the Battle of Roliça and the Battle of Vimeiro in 1808. Unfortunately, Wellesley was superseded in command of the British army. General Dalrymple insisted on connecting the available government minister to the controversial Convention of Sintra, which stipulated that the British Royal Navy would transport the French army out of Lisbon with all their loot. Wellesley was recalled to Britain to face a Court of Enquiry. He had agreed to sign the preliminary Armistice, but had not signed the Convention, and was cleared.

Meanwhile, Napoleon himself went to Spain with his veteran troops, and the new commander of the British forces in the peninsula, Sir John Moore, died during the Battle of Corunna.

Although the war was not going particularly well, it was the one place where the Portuguese and the British had managed to put up a fight against France and her allies. (The disastrous Walcheren expedition was typical of the mismanaged British expeditions of the time.) Wellesley submitted a memorandum to Lord Castlereagh on the defence of Portugal. Castlereagh appointed him head of the British forces in Portugal and raised their number from 10,000 men to 26,000.

Quickly reinforced, Wellesley took the offensive in April 1809. First, he crossed the Douro river in a brilliant daylight coup de main, and routed the French troops in Porto. He then joined with a Spanish army under Cuesta. They meant to attack Victor, but Napoleon's brother Joseph Bonaparte reinforced Victor, and the French attacked and lost at the Battle of Talavera de la Reina. For this, he was ennobled as Viscount Wellington of Talavera and of Wellington. (His brother Richard selected the name Wellington for its similarity to the family name of Wellesley.) With Soult threatening his rear, the British were compelled to retreat to Portugal. Deprived of supplies promised by the Spanish throughout the campaign and not told of Soult's movement, Wellington never again relied on Spanish promises or resources.

In 1810 the French army under Marshal André Masséna invaded Portugal. Wellington first slowed them down at Busaco, then blocked them from taking the Lisbon peninsula by his magnificently constructed earthwork Lines of Torres Vedras coupled with the support of the Royal Navy. The baffled and starving French invasion forces retreated after six months. Wellington followed and in several skirmishes, drove them out of Portugal, except for a small garrison at Almeida which was placed under siege.

In 1811, Masséna returned to Portugal to relieve Almeida, but Wellington narrowly defeated the French at the battles of Fuentes de Oñoro. Meanwhile, Wellington's subordinate, Viscount Beresford, fought Marshal Soult's 'Army of the South' to a bloody standstill at the Battle of Albuera. In May, he was promoted to general for his services. Almeida fell, but the French retained the twin fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, the 'Keys' guarding the roads into Portugal throughout the year.

In 1812, Wellington finally captured Ciudad Rodrigo by moving as the French went into winter quarters and storming it before they could react. Moving south quickly, he stormed the fortress of Badajoz in one bloody night. the Storming of Badajoz is famous as the only time he ever lost his composure, breaking down and crying at the sight of British dead in the breaches.

His army now was a British force reinforced in all divisions by units of the resurgent Portuguese army, rebuilt by Beresford. Campaigning in Spain, he routed the French at Salamanca, proving he could attack as well defend. (This was the first time a French army of 50,000 had been routed since 1799.) The victory liberated the Spanish capital of Madrid. In this year he was created Earl and then Marquess of Wellington and given command of all Allied armies in Spain.

He attempted to take the vital fortress of Burgos, but failed due to a lack of siege equipment. The French abandoned Andalusia, and converged that and other armies to put the British forces in a precarious position. Wellington skillfully withdrew his army and joining with the smaller corps commanded by Rowland Hill, retreated to Portugal. Still, his victory at Salamanca had forced the French to withdraw from southern Spain, and the temporary loss of Madrid irreparably damaged the pro-French puppet government.

In 1813, Wellington led a new offensive against the French line of communication. He struck through the hills north of Burgos, and unexpectedly drew his supplies from Santander (on Spain's north coast), rather than from Portugal. He personally led a small force in a feint against the French centre, while the main army (commanded by Sir Thomas Graham) looped around the French right, leading to the French abandoning Madrid and Burgos. Continuing to outflank the French lines, Wellington brought the French to battle at Vitoria, for which he was promoted to field marshal. (However, the British troops broke discipline to loot the abandoned French wagons instead of pursuing the beaten foe. Wellington, in his official after-battle report, furiously and famously called them "the scum of the earth, enlisted only for drink".)

A few months later, after taking the small fortresses of Pamplona and San Sebastián, Wellington invaded France and defeated the French army under Marshal Soult at the Battle of Toulouse. (Ironically, this occurred four days after Napoleon had already surrendered in the East.) Napoleon was then exiled to the island of Elba in 1814.

Hailed as the conquering hero, Wellington was created Duke of Wellington, a title still held by his descendants. (Since he had not returned to England during the entire Peninsular War, he was awarded all his patents of nobility in a remarkable ceremony lasting an entire day.) He was soon appointed ambassador to France, then took Lord Castlereagh's place as First Plenipotentiary to the Congress of Vienna, where he strongly advocated allowing France to keep its place in the European balance of power. On 2 January 1815, the title of his Knighthood of the Bath was converted to Knight Grand Cross upon the expansion of that order.

On 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and returned to France. Regaining control of the country by May, he faced a renewed alliance against him. Wellington left Vienna to command the Anglo-Allied forces during the Waterloo Campaign. He arrived in Belgium to take command of the British army and the allied Dutch-Belgians, alongside the Prussian forces of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. The French defeated the Prussians at Ligny, and fought an indecisive battle at Quatre Bras, compelling the British army to retreat to a ridge on the Brussels road, just south of the small town of Waterloo. Two days later, on 18 June, came the titanic Battle of Waterloo. After an all-day fight, with the French discomfited by the unexpected arrival of Blücher's Prussian army, the French Imperial Guard was dramatically repulsed by British volley fire, routing Napoleon's army. On 22 June, the French Emperor abdicated once again, and was transported by the British to distant St Helena.

Wellington as soldier

Despite frequently cited similarities between Napoleon Bonaparte and Wellington, the strategies and tactics employed by them were diametrically opposed. Perhaps the main reason that Napoleon stands in many history texts above Wellington is that Napoleon offered radical changes in warfare in every respect, whereas Wellington's contribution to warfare lay more in his brilliant use of the old ways.

Napoleon's tactics were typified by massive conscript armies who advanced in tight columns to rout opposing forces. This tactic originated with Frederick the Great, and was soon adopted by nearly every major participant in the war, with the chief exception of the British, and the Portuguese and Spanish troops they trained. In almost every engagement, the tight-packed French columns (in which only the first two ranks and outer edges could fire) would advance, apparently unheeding of casualties. Against the ill-trained and panic-prone armies of the Austrians and the other allied powers, it was spectacularly successful. Against the disciplined and trained British regulars who stood in line in two ranks (thus permitting every man in line to fire), the column was a dramatic failure. Despite the demonstrated helplessness of the French columns against the British line, the French commanders in Iberia continued to attack in column. (Indeed, column attacks were used even at the Battle of Waterloo.) Thus, in many instances, a single British battalion would defeat an entire French division.

Wellington is often viewed as a defensive general, despite the fact that many of his greatest victories ( Assaye, Porto, Salamanca, Vitoria, Toulouse), were offensive battles. In fact, when on the defensive Wellington actually made mistakes, most famously at the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, where his disastrous misplacement of a division was only retrieved by his quick thinking and the steadiness of the British and Portuguese troops in retreating under fire.

Strategically, Wellington also appears somewhat anachronistic, with the Peninsular War revolving partly around the possession and besieging of fortified strongholds. Conventional military wisdom of the era, especially under Napoleon, dictated that the opposing field army was to be eliminated at any price, before disease and wastage could reduce the attacking force to nothing. In pursuit of this aim, desperate measures would be taken, such as winter battles, forced marches, and privation alleviated only by foraging. Wellington's campaigns instead were marked by carefully planned offensives, supported by a magnificent supply train, and tempered by subsequent consolidation of gains.

In other strategic areas however, Wellington seemed to foresee the tide of the future. His construction of the fortifications near Torres Vedras, and the subsequent attritional campaign which ensued, seems to typify the evolution of warfare in the following century. He also cooperated closely with the British navy, a necessity for success on the water-bound Iberian Peninsula.

Tactically, Wellington capitalized on the reforms of Sir John Moore and the Duke of York by creating large units of independent infantry, often armed with rifles, who fought in both regular and irregular fashion. His relationship with his cavalry arm — as well as his cavalry commanders — was infamously stern and demanding. Wellington was never satisfied with the performance of his cavalry, and he continued to consider them undisciplined in the charge stating:

"...a trick our officers have acquired of galloping at everything and then galloping back as fast as they galloped on the enemy. They never consider their situation, never think of manoeuvring before an enemy - so little that one would think they cannot manoeuvre except on Wimbledon Common; and when they use their arm as it ought to be used, viz. offensively, they never keep nor provide for a reserve." (Redcoat, p. 225)

However, Wellington and commanders such as Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey and John Gaspard le Marchant made the cavalry arm among the most effective in the army, producing decisive results at Assaye, Salamanca, and Waterloo. The latter saw the Earl of Uxbridge's use of two cavalry brigades to rout an entire French corps, though the cavalry's lack of discipline immediately after its magnificent charge destroyed its effectiveness for the rest of the day.

Wellington should also be considered a model for multi-national leadership. He efficiently coordinated the efforts of Portuguese, Spanish, and a multitude of other foreign units, as well as negotiating with a home government not always sympathetic to his military concerns. It is a testament to Wellington's ability that he successfully integrated and commanded British, Spanish, Portuguese, Hanoverian, Saxon, Prussian, Swiss, Indian, Dutch, and Belgian troops; a retinue probably only Napoleon himself could match. In command of these forces, he was almost always outnumbered, and succeeded by the merits of his attention to detail and tactical foresight.

An important point when comparing Wellington and Napoleon is that whereas Napoleon was supreme commander of the armed forces of his Empire, Wellington was merely a general in the field, with little or no influence on the organisation or administration of the British Army as a whole. He was driven to exasperation on several occasions, for example by the fact that his artillery and engineers were administered separately from the infantry and cavalry, and by the quality of some of the commanders and staff officers foisted on him by the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of York. (For example, General Erskine was appointed second in command of the cavalry; Wellington considered him both incompetent and mad, and only Erskine's suicide finally removed him from the scene.)

However, when Wellington himself became commander-in-chief, he made no major changes to the Army's policies, maintaining practices such as purchase of commissions and flogging for disciplinary offences unchanged for almost forty years. He is often criticised for being 'brutal' in this respect, but it must be remembered that, good or bad, this was typical and accepted practice in the British armed forces at the time.

Later life

Politics beckoned once again in 1819, when Wellington was appointed Master-General of the Ordnance in the Tory government of Lord Liverpool. In 1827, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. Along with Robert Peel, Wellington became one of the rising stars of the Tory party, and in 1828 he became Prime Minister.

During his first seven months as Prime Minister he chose not to live in the official residence at 10 Downing Street, finding it too small. He only relented and moved in because his own home, Apsley House, required extensive renovations.

As Prime Minister, Wellington was the picture of the arch-conservative, fearing that the anarchy of the French Revolution would spread to England. Oddly enough, the highlight of his term was Catholic Emancipation, the granting of almost full civil rights to Catholics in the United Kingdom. The change was forced by the landslide by-election win of Daniel O'Connell, a Catholic proponent of emancipation, who was elected despite not being legally allowed to sit in Parliament. Lord Winchilsea accused the Duke of having "treacherously plotted the destruction of the Protestant constitution". Wellington responded by immediately challenging Winchilsea to a duel. On 21 March 1829, Wellington and Winchilsea met on Battersea fields. When it came time to fire, the Duke deliberately aimed wide and Winchilsea fired into the air. He subsequently wrote Wellington a grovelling apology. In the House of Lords, facing stiff opposition, Wellington spoke for Catholic emancipation, giving one of the best speeches of his career . He had grown up in Ireland, and later governed it, so he knew firsthand of the misery of the Catholic masses there. The Catholic Relief Act 1829 was passed with a majority of 105. Many of the Tories voted against the Act, and it passed only with the help of the Whigs.

The epithet "Iron Duke" originates from his period of Prime Minister, during which he experienced an extremely high degree of personal and political unpopularity. His residence at Apsley House was the constant target of window-smashers and iron shutters were installed to mitigate the damage. It was this rather than his characteristic, resolute constitution, that earned him the epithet of "The Iron Duke".

Wellington's government fell in 1830. In the summer and autumn of that year, a wave of riots (the Swing Riots) swept the country. The Whigs had been out of power for all but a few years since the 1770s, and saw political reform in response to the unrest as the key to their return. Wellington stuck to the Tory policy of no reform and no expansion of the franchise, and as a result lost a vote of no confidence on 15 November 1830. He was replaced as Prime Minister by Earl Grey.

The Whigs introduced the first Reform Act, but Wellington and the Tories worked to prevent its passage. The bill passed in the House of Commons, but was defeated in the House of Lords. An election followed in direct response, and the Whigs were returned with an even larger majority. A second Reform Act was introduced, and defeated in the same way, and another wave of near insurrection swept the country. During this time, Wellington was greeted by a hostile reaction from the crowds at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and eventually the bill was passed after the Whigs threatened to have the House of Lords packed with their own followers if it were not. Though it passed, Wellington was never reconciled to the change; when Parliament first met after the first election under the widened franchise, Wellington is reported to have said "I never saw so many shocking bad hats in my life". During this time Wellington was gradually superseded as leader of the Tories by Robert Peel. When the Tories were brought back to power in 1834 Wellington declined to become prime minister, and Peel was selected instead. Unfortunately Peel was in Italy, and for three weeks in November and December 1834, Wellington acted as a caretaker, taking the responsibilities of Prime Minister and most of the other ministries. In Peel's first cabinet (1834–1835), Wellington became Foreign Secretary, while in the second (1841–1846) he was a Minister without Portfolio and Leader of the House of Lords.

Wellington retired from political life in 1846, although he remained Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, and returned briefly to the spotlight in 1848 when he helped organize a military force to protect London during that year of European revolution. He died in 1852 at Walmer Castle (his honorary residence as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, which he enjoyed and at which he hosted Queen Victoria). Although in life he hated travelling by rail, his body was then taken by train to London, where he was given a state funeral - one of only a handful of British subjects to be honoured in that way (other examples are Nelson and Churchill) - and was buried in a sarcophagus of luxulyanite in St Paul's Cathedral.

Legacy

In 1838 a proposal to build a statue of Wellington resulted in the building of a giant statue of him on his horse Copenhagen, placed above the Arch at Constitution Hill in London directly outside Apsley House, his former London home. Completed in 1846, the enormous scale of the 40 ton, 30 feet high monument resulted in its removal in 1883, and the following year it was transported to Aldershot where it still stands near the Royal Garrison Church.

The capital city of New Zealand is named Wellington in honour of Wellington. The city has a private preparatory school named Wellesley College and a private club, Wellesley Club. The city of Auckland, New Zealand, has a central city road named Wellesley Street after Arthur Wellesley.

HMS Iron Duke, named after Wellington, was the flagship of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe at the Battle of Jutland in World War I.

Wellington Street in Ottawa, Canada is named after Wellington. It is the street upon which the Parliament Buildings, Canada's seat of government are located.

Titles and honours

Peerage of the United Kingdom

- Baron Douro, of Wellington in the County of Somerset (4 September 1809)

- Viscount Wellington, of Talavera and of Wellington in the County of Somerset (4 September 1809)

- Earl of Wellington, in the County of Somerset (28 February 1812)

- Marquess of Wellington, in the County of Somerset (3 October 1812)

- Marquess Douro (11 May 1814)

- Duke of Wellington, in the County of Somerset (11 May 1814)

British and Irish honours

- Knight of the Bath (1804)

- Privy Councillor of Great Britain (8 April 1807)

- Privy Councillor of Ireland (28 April 1807)

- Knight of the Garter (4 March 1813)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (1815)

- Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire (1820)

- Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1829)

- Peninsular Cross medal with nine bars for all campaigns — the only one so issued. Displayed at Apsley House along with a Waterloo Medal.

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1847)

- Chancellor of Oxford University (1834-1852)

International honours and titles

- Conde de Vimeiro (18 October 1811, Portugal)

- Duque de Ciudad Rodrigo (January 1812, Spain)

- Grandee of the First Class (January 1812, Spain)

- Marquês de Torres Vedras (August 1812, Portugal)

- Duque da Vitória (Duke of the Victory) (18 December 1812, Portugal)

- Knight of the Golden Fleece (1812, Spain)

- Prins van Waterloo (18 July 1815, The Netherlands)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Hanover (1816, Hanover)

- Field Marshal batons from 12 countries. These can be seen at Apsley House.

The Duke of Wellington stood as godfather to Queen Victoria's seventh child, Prince Arthur, in 1850. The Duke of Wellington and his godson shared the same birthday, and as a toddler, young Arthur was encouraged to remind people that the Duke of Wellington was his godfather.

Styles

- The Hon. Arthur Wesley (birth–7 March 1787)

- Ensign The Hon. Arthur Wesley (7 March 1787–25 December 1787)

- Lieutenant The Hon. Arthur Wesley (25 December 1787–30 June 1791)

- Captain The Hon. Arthur Wesley (30 June 1791–30 April 1793)

- Major The Hon. Arthur Wesley (30 April 1793–30 September 1793)

- Lieutenant-Colonel The Hon. Arthur Wesley (30 September 1793–3 May 1796)

- Colonel The Hon. Arthur Wesley (3 May 1796–19 May 1798)

- Colonel The Hon. Arthur Wellesley (19 May 1798–29 April 1802)

- Major-General The Hon. Arthur Wellesley (29 April 1802–1 September 1804)

- Major-General The Hon. Sir Arthur Wellesley, KB (1 September 1804–8 April 1807)

- Major-General The Rt Hon. Sir Arthur Wellesley, KB (8 April 1807–25 April 1808)

- Lieutenant-General The Rt Hon. Sir Arthur Wellesley, KB (25 April 1808–4 September 1809)

- Lieutenant-General The Rt Hon. The Viscount Wellington, KB, PC (4 September 1809–May 1811)

- General The Rt Hon. The Viscount Wellington, KB, PC (May 1811–28 February 1812)

- General The Rt Hon. The Earl of Wellington, KB, PC (28 February 1812–3 October 1812)

- General The Most Hon. The Marquess of Wellington, KB, PC (3 October 1812–4 March 1813)

- General The Most Hon. The Marquess of Wellington, KG, KB, PC (4 March 1813–21 June 1813)

- Field Marshal The Most Hon. The Marquess of Wellington, KG, KB, PC (21 June 1813–11 May 1814)

- Field Marshal His Grace The Duke of Wellington, KG, KB, PC (11 May 1814–2 January 1815)

- Field Marshal His Grace The Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, PC (2 January 1815–14 September 1852)

Nicknames

Apart from giving his name to " Wellington boots", the Duke of Wellington also had several nicknames.

- The " Iron Duke", after an incident in 1830 in which he installed metal shutters to prevent rioters breaking windows at Apsley House

- Officers under his command called him "The Beau", he being a fine dresser or "The Peer" after he was created a Viscount.

- Regular soldiers under his command called him "Old Nosey" or "Old Hookey" because of his long nose.

- Spanish and Portuguese troops called him "the Eagle" and "Douro" respectively.

Misattributed quotations

- The epigram "the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton" was never said by Wellington (it was invented by a French journalist), and could not have been: he remembered his days at Eton as lonely and unhappy, his only sport being solitary leaps across a local brook, and he almost never visited the school in after years despite being its most famous alumnus.

- The exclamation "Publish and be damned!" is attributed to Wellington, as what he said after the courtesan Harriette Wilson threatened to publish her memoirs and his letters if he did not supply her financial demands.

Personality traits

Wellington set a gruelling pace of work. He rose early - he "couldn't bear to lie" in once awake - and usually slept six hours or less. Even when he returned to civilian life after 1815, he slept in a camp bed, reflecting his lack of regard for creature comforts.

Never much of a gourmet, he frequently drove his chef to frustration by his abstemious ways and general lack of interest in food, even eating a rotten egg on one occasion without realising it. Whilst on campaign he seldom ate anything between breakfast and dinner. During the retreat back to Portugal during 1811, he subsisted (to the despair of his staff who dined with him) on "cold meat and bread". He was however renowned for the excellent quality of the wine he drank and served (often drinking a bottle with his dinner - not a great quantity by the standards of his day).

Although by no means ostentatious, the Duke was renowned for his fine sartorial taste (which, as mentioned above, helped earn him the nickname of "The Beau"). He was particularly fond of trousers - only just entering the gentleman's wardrobe during his life time. On one occasion the Duke was turned away from the Almack's Assembly Rooms (a popular haunt of high society) for wearing trousers rather than the more conventional knee breeches. Despite his luminary status, he quietly left without a word of protest.

He was very fond of high-technology and mechanical gadgets.

He was very insistent that he was not interrupted during shaving (possibly because his unusually rapid growth of facial hair required him to shave twice a day).

In fiction

- Wellington is a recurring character in the Richard Sharpe novels by Bernard Cornwell. In the film versions he was played by David Troughton for the first two instalments and Hugh Fraser for the remainder of the 14 movie series.

- He was memorably (if unflatteringly) portrayed by Stephen Fry in the "Duel and Duality" episode of the BBC One comedy television series Blackadder as a shouting, blustering war maniac with a tendency of violence towards the lower orders (including the Prince Regent, who was at the time disguised as his own butler, Mr. E. Blackadder) and a penchant for duelling with cannon (because "only girls fight with swords these days"). Fry later reprised his role, this time in a more historically accurate manner, in Blackadder: Back & Forth.

- C. S. Forester invented a younger sister, "Lady Barbara Wellesley", as a character in his Horatio Hornblower novels.

- In Susanna Clarke's novel Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, Wellington appears as the British Army's commanding officer in Portugal and Spain. He employs Jonathan Strange to help defeat the French using magic. He also appears as himself in Clarke's collection of short stories, The Ladies of Grace Adieu, in The Duke of Wellington Misplaces His Horse: Wellington follows his famous horse Copenhagen into Faerie.

- An 82 year old Wellington was portrayed by Ron Moody in the Doctor Who audio play Other Lives, in which the Duke met the Doctor and his companions at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The Duke of Wellington's Government, January 1828 – November 1830

- The Duke of Wellington— First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords

- Lord Lyndhurst— Lord Chancellor

- Lord Bathurst— Lord President of the Council

- Lord Ellenborough— Lord Privy Seal

- Robert Peel— Secretary of State for the Home Department and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Dudley— Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- William Huskisson— Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

- Henry Goulburn— Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Charles Grant— President of the Board of Trade and Treasurer of the Navy

- Lord Melville— President of the Board of Control

- John Charles Herries— Master of the Mint

- Lord Aberdeen— Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Palmerston— Secretary at War

Changes

- May-June, 1828— Sir George Murray succeeded Huskisson as Colonial Secretary. Lord Aberdeen succeeded Lord Dudley as Foreign Secretary. Aberdeen's successor at the Duchy of Lancaster was not in the cabinet. William Vesey-FitzGerald succeeded Grant as President of the Board of Trade and Treasurer of the Navy. Lord Palmerston left the Cabinet. His successor as Secretary at War was not in the cabinet.

- September, 1828— Lord Melville became First Lord of the Admiralty. He was succeeded as President of the Board of Control by Lord Ellenborough, who also remained Lord Privy Seal

- June, 1829— Lord Rosslyn succeeded Lord Ellenborough as Lord Privy Seal. Ellenborough remained at the Board of Control.

The Duke of Wellington's Caretaker Government November 1834 – December 1834

- The Duke of Wellington— First Lord of the Treasury, Secretary of State for the Home Department, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies and Leader of the House of Lords

- Lord Lyndhurst— Lord Chancellor

- Lord Denham— Chancellor of the Exchequer

Other offices were in commission.