Alpaca

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mammals

| iAlpaca | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Domesticated

|

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Vicugna pacos (Linnaeus, 1758) |

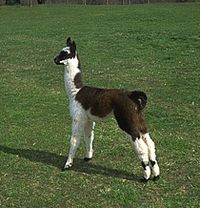

The Alpaca (Vicugna pacos) is a domesticated breed of South American camel-like ungulates, derived from the wild vicuña. It resembles a sheep in appearance, but is larger and has a long erect neck.

Alpacas are kept in herds that graze on the level heights of the Andes of southern Peru, northern Bolivia, and northern Chile at an altitude of 3500 to 5000 meters above sea-level, throughout the year. Alpacas are considerably smaller than llamas and unlike them are not used as beasts of burden but are valued only for their fibre (wool), used for making blankets and ponchos in South America, and sweaters, blankets, socks and coats in other parts of the world. The fibre comes in more than 22 natural colours.

In the textile industry, "alpaca" primarily refers to the hair of Peruvian alpaca, but more broadly it refers to a style of fabric originally made from alpaca hair but now often made from similar fibers, such as mohair, Icelandic sheep wool, or even high-quality English wool. In trade, distinctions are made between alpacas and the several styles of mohair and lustre. However, as far as the general purchaser is concerned, little or no distinction is made.

Background

Alpacas have been domesticated for thousands of years. There are no wild alpacas; they were bred down in domesticated form from the vicuña, which is also native to South America. They are closely related to llamas, which are descended from the guanaco. These four species of animals are collectively called camelids.

Of the four, the alpaca and the vicuña are the most valuable fiber-bearing animals: the alpaca because of the quality and quantity of its fiber, and the vicuña because of the softness, fineness and quality of its coat. Alpacas cannot carry pack loads like their llama cousins; they were bred exclusively for their fibre and meat.

Alpacas and llamas can (and do) successfully cross-breed. The resulting offspring are called huarizo, and have little "real purpose," but often have gentle temperaments and are suitable for pets.

There are two types of alpaca – Huacaya (with dense, crimpy sheep-like fiber) and Suri (with silky dreadlocks). Suri fiber is often preferred by spinners, because it is long and has a silky luster. Suris are much rarer than Huacayas, and are estimated to make up between 6 and 10% of the alpaca population. However, since its import into the United States through Bill Barnett, the Suri is growing substantially in number and colour diversity. The Suri is thought to be rarer possibly because it is less hardy in the harsh South American mountain climates, as its fleece offers less insulation against the cold. The Suri fleece parts along the spine, exposing the animal to the cold, unlike the Huacaya fleece which provides excellent cover over the backbone. Hoffman ( page 279) states that the word suri comes from the rhea, a flightless ostrich-like bird from Patagonia. The fact that the name is shared with that of the bird supports the belief that suris developed in the lowlands and were forced to live in higher areas by the actions of the Spanish invaders. However there is little evidence of any sort on this topic, so suri origins can only be the subject of speculation.

Alpaca fleece is a luxurious fibre, similar to sheep’s wool in some respects, but lighter in weight, silkier to the touch, warmer, not prickly and bears no lanolin, making it nearly hypoallergenic. A big trade of alpaca fleece exists in the countries where alpacas live, from very simple and not so expensive garments made by the aboriginal communities, to sophisticated, industrially made and expensive products. In the United States, groups of smaller alpaca breeders have banded together to create "fibre co-ops," to make the manufacture of alpaca fibre products much cheaper.

White is the predominant colour of alpacas, both Suri and Huacaya. This is because South American selective breeding has favoured white — bulk white fleece is easier to market and can be dyed any colour. However, alpacas come in more than 22 natural colour shades, from a true-blue black through browns-and-fawns to white, and there are silver-greys and rose-greys as well. In South America, the preference is for white, and white animals generally have better fleece than darker-colored animals. However, in the United States, more and more people desire darker fiber, especially blacks and greys. Thus, breeders have been diligently working on breeding dark animals with exceptional fibre, and much progress has been made in these areas over the last 5-7 years.

Traditionally, alpaca meat has been eaten fresh, fried or in stews, by Andean inhabitants. There is a resurgent interest in alpaca meat in countries like Peru, where it is relatively easy to find it at upscale restaurants.

Behaviour

Alpacas are social herd animals and should always be kept with others of their kind, or at the very least with other herd animals. They are gentle, elegant, inquisitive, intelligent and observant. As they are a prey animal, they are cautious and nervous if they feel threatened. They like having their own space and do not like an unfamiliar alpaca or human getting close, especially from behind. They warn the intruder away by making sharp, noisy inhalations, putting back their ears, twisting their heads and necks backwards toward the perceived threat, screaming, threatening to spit, and eventually may spit and kick. Due to the soft pads on their feet, the kicks are not as dangerous as those of hoofed animals.

Spitting

Not all alpacas spit, but all are capable. "Spit" is somewhat euphemistic. While occasionally the projectile contains only air and a little saliva, the alpaca often bring up and project regurgitated stomach contents.

Spitting is mostly reserved for other alpacas, not for humans, but sometimes a human gets in the line of fire. If an alpaca is extremely displeased at a human, that person may well become covered in smelly, green goo. The smell is so foul that many people who work with alpacas would much rather come into contact with alpaca feces than with alpaca spit.

For alpacas, spitting results in what is called "sour mouth." Sour mouth is characterized by a loose-hanging lower lip and a gaping mouth. This is caused by the stomach acids and unpleasant taste of the contents as they pass out of the mouth.

Some alpacas will spit when looked at, others will never spit — their personalities are all so individualized that there is no hard and fast rule about them in terms of social behaviour.

Physical contact

Alpacas generally do not like their heads being touched. Once they know their owners and feel confident around them, they may allow their backs and necks to be touched. They do not like being grabbed, especially by boisterous children. This is probably because when alpacas are caught up for medical or otherwise unpleasant procedures, people generally grab their necks and hold them by the neck and head. Once socialized well, most alpacas tolerate being stroked or petted anywhere on their bodies, although many do not like their feet and lower legs handled. If an owner needs to catch an alpaca, the neck offers a good handle — holding the neck firmly between the arms is the best way to restrain the animal.

Hygiene

To help alpacas control their internal parasites they have a communal dung pile, which they do not graze. Generally, males have much tidier dung piles than females who tend to stand in a line and all go at once. One female approaches the dung pile and begins to urinate and/or defecate, and the rest of the herd often follows.

Because of their preference to using a dung pile, some alpacas have been successfully house-trained. Difficult though it may be to conceive of having a large animal such as a full-grown alpaca around the household, many owners so love their animals that they wish to be in their presence as much as possible. If acclimated to dogs and cats, alpacas can accept them as members of the herd, and interact with nearly all species which do not pose a threat, from birds and butterflies to horses and humans.

Sounds

Individuals vary, but Alpacas generally make a humming sound. Hums are often comfort noises, letting the other alpacas know they are present and content. However, humming can take on many inflections and meanings, from a high-pitched, almost desperate, squealing, "MMMM!" or frantic question, "mmMMM!" when a mother is separated from her offspring (called a "cria,") to a questioning "Mmm?" when they are curious.

Alpacas also make other sounds as well as humming. In danger, they make a high-pitched, shrieking whine. Some breeds are known to make a "wark" noise when excited, and they stand proud with their tails sticking out and their ears in a very alert position. Strange dogs — and even cats — can trigger this reaction. To signal friendly and/or submissive behaviour, alpacas "cluck," a sound possibly generated by suction on the soft palate, or possibly somehow in the nasal cavity. This is often accompanied by a flipping up of the tail over the back.

When males fight they also scream, a warbling bird-like cry, presumably intended to terrify the opponent. Fighting is to determine dominance, and therefore the right to mate the females in the herd, and it is triggered by testosterone. This is why males are often kept in separate paddocks — when two dominant males get together violent fights often occur. When males must be pastured together, it is wise to trim down the large fang-like teeth used in fights, called "fighting teeth".

Reproduction

A male in the act of mating, or hoping for a chance to mate, "orgles." This orgling helps to put the female in the mood, and it is believed to also help her to ovulate after mating.

Females have no estrus cycle — they are "induced ovulators," which means that the act of mating and the presence of semen causes them to ovulate. Occasionally, females conceive after just one breeding (which can last anywhere from 5 minutes to well over an hour; the males are "dribble ejaculators,") but occasionally do have troubles conceiving. Artificial insemination is prohibitively expensive and there are complications with the process in camelid species.

A male is usually ready to mate for the first time at a year of age, but a female alpaca is not fully mature (physically and mentally) until she reaches approximately 16-18 months, and it is not advisable to breed a female earlier.

The male's penis is attached to the inside of his body, and generally does not detach until at least two years of age. The penis is a very long, thin, prehensile organ that is, oddly enough, perfectly designed for the task of finding the vaginal opening despite a fluffy tail, penetrating the hymen (if present,) navigating the vaginal canal and entering the cervical opening, where deposit of the semen occurs.

Pregnancies last 11 to 11.5 months and the young are called crias. After a female gives birth, she is generally receptive to breeding again after approximately 15 days. Crias may be weaned through human intervention at approximately 6 months and 60 pounds. However, many breeders prefer to allow the female to decide when to wean her offspring.

It is believed that alpacas generally live for more than 20 years. Conditions and nutrition are better in the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Europe than in South America, so animals live longer and are healthier. One of the oldest alpacas in New Zealand (fondly called Vomiting Violet) died at the end of 2005 at the old age of 29.

History of the scientific name

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the four South American camelid species were assigned scientific names. At that time, the alpaca was assumed to be descended from the llama, ignoring similarities in size, fleece and dentition between the alpaca and the vicuña. Classification was complicated by the fact that all four species of South American camelid can interbreed and produce fertile offspring. It was not until the advent of DNA technology that a more accurate classification was possible.

In 2001, the alpaca genus classification changed from Lama pacos to Vicugna pacos following the presentation of a paper on work by Dr Jane Wheeler et al on alpaca DNA to the Royal Society showing that the alpaca is descended from the vicuña, not the guanaco.

The relationship between alpacas and vicuñas was disputed for many years, but Wheeler's DNA work proved it. However many academic sites have not caught up with this, so it is something well known to alpaca breeders who have read Dr Hoffman's book, and to Royal Society members who have access to the current classification data, but not more widely known.

Fibre

Alpaca fiber is warmer than sheep's wool and lighter in weight. It is soft and luxurious and lacks the "prickle" factor. However, as with all fleece-producing animals, quality varies from animal to animal, and some alpaca produce fiber which is less than ideal. Fiber and conformation are the two most important factors in determining an alpaca's value. Animals from the Peruvian Accoyo line often have the best fiber characteristics. The Accoyo estancia of Peru practiced "line breeding" (breeding granddaughters to their grandfathers and so forth, much like dog breeders do,) and they managed to create exceptional fibre. Most Accoyo animals (both Suri and Huacaya) are white, although with diversification, there are some darker Accoyo animals.

Alpaca have been bred in South America for thousands of years (vicuñas were first domesticated and bred into alpacas by the ancient Andean tribes of Peru, but also appeared in Chile and Bolivia,) but in recent years have been exported to other countries. In countries such as the USA, Australia and New Zealand breeders shear their animals annually, weigh the fleeces and test them for fineness. With the resulting knowledge they are able to breed heavier-fleeced animals with finer fibre. Fleece weights vary, with the top stud males reaching annual shear weights up to 6kg.

In physical structure, alpaca fibre is somewhat akin to (human?) hair, being very glossy, but its softness and fineness enable the spinner to produce satisfactory yarn with comparative ease. Alpaca fibre can even be spun into yarn with one's fingers.

Alpaca fibre industry

History

The Amerindians of Peru, a country in South America, used this fibre in the manufacture of many styles of fabrics for thousands of years before its introduction into Europe as a commercial product. The alpaca was a crucial component of ancient life in the Andes, as it provided not only warm clothing but also meat. Many rituals revolved around the alpaca, perhaps most notably the method of killing it: An alpaca was restrained by one or more people, and a specially-trained person plunged his bare hand into the chest cavity of the animal, ripping out its heart. Today, this ritual is viewed by most as barbaric, but there are still some tribes in the Andes which practice it.

The first European importations of alpaca fibre were into Spain. Spain transferred the fibre to Germany and France. Apparently alpaca yarn was spun in England for the first time about the year 1808 but the fibre was condemned as an unworkable material. In 1830 Benjamin Outram, of Greetland, near Halifax, appears to have reattempted spinning it, and again it was condemned. These two attempts failed due to the style of fabric into which the yarn was woven — a species of camlet. It was not until the introduction of cotton warps into Bradford trade about 1836 that the true qualities of alpaca could be developed in the fabric. It is not known where the cotton warp and mohair or alpaca weft plain-cloth came from, but it was this simple and ingenious structure which enabled Titus Salt, then a young Bradford manufacturer, to use alpaca successfully. Bradford is still the great spinning and manufacturing centre for alpaca. Large quantities of yarns and cloths are exported annually to the European continent and the US, although the quantities vary with the fashions in vogue. The typical "alpaca-fabric" is a very characteristic " dress-fabric."

Due to the successful manufacture of various alpaca cloths by Sir Titus Salt and other Bradford manufacturers, a great demand for alpaca wool arose, which could not be met by the native product. Apparently, the number of alpacas available never increase appreciably. Unsuccessful attempts were made to acclimatize alpaca in England, on the European continent and in Australia, and even to cross English breeds of sheep with alpaca. But there is a cross between alpaca and llama — a true hybrid in every sense — producing a material placed upon the Liverpool market under the name "Huarizo". Crosses between the alpaca and vicuña have not proved satisfactory. Current attempts to cross these two breeds are underway at farms in the US. According to the Alpaca Owners and Breeders Association, alpacas are now being bred in the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, UK, and numerous other places.

In recent years, interest in alpaca fibre clothing has surged, perhaps partly because alpaca ranching has a reasonably low impact on the environment. Outdoor sports enthusiasts recognize that its lighter weight and better warmth provides them more comfort in colder weather, so outfitters such as R.E.I. and others are beginning to stock more alpaca products. Occasionally, alpaca fibre is woven together with merino wool to attain even more softness and durability.

The preparing, combing, spinning, weaving and finishing process of alpaca and mohair are similar to that of wool.

Farmers commonly quote the alpaca with the phrase 'love is in the fleece', which describes their love for the animal.

Prices

The price for alpacas can range from US$100 to US$1,060,000, depending on breeding history, sex, and colour. It is possible to raise up to 10 alpacas on one acre (4,047 m²) as they have a designated area for waste products and keep their eating area away from their waste area to avoid diseases. But this ratio differs from country to country and is highly dependent on the quality of pasture available (in Australia it is generally only possible to run one to three animals per acre). Fibre quality is the primary variant in the price achieved for alpaca wool, in Australia it is common to classify the fibre by the thickness of the individual hairs and by the amount of vegetable matter contained in the supplied shearings.

US speculative bubble

A research paper on this topic published by the Agricultural Issues Centre of the University of California in 2005 examined the US alpaca industry and concluded: current prices for alpaca stock are not supportable by market fundamentals and that the industry represents the latest in the rich history of speculative bubbles.