Ostrich

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Birds

| iOstrich | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

Least Concern (LC) |

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758 |

The ostrich (Struthio camelus) is a flightless bird native to Africa. It is the only living species of its family, Struthionidae, and its genus, Struthio. They are distinct in their appearance, with a long neck and legs and the ability to run at speeds of about 65 km/h (40 mph). Ostriches are the largest living species of bird and are farmed in many areas all over the world. The scientific name for the ostrich is from the Greek for "camel sparrow" in allusion to their long necks.

Description

Ostriches usually weigh from 90 to 130 kg (200 to 285 pounds), although some male ostriches have been recorded with weights of up to 155 kg (340 pounds). The feathers of adult males are mostly black, with some white on the wings and tail. Females and young males are grayish-brown, with a bit of white. The small vestigial wings are used by males in mating displays. They can also provide shade for chicks. The feathers are soft and serve as insulation, and are quite different from the stiff airfoil feathers of flying birds. There are claws on two of the wings' fingers. The strong legs of the ostrich lack feathers. The bird stands on two toes, with the bigger one resembling a hoof. This is an adaptation unique to ostriches that appears to aid in running.

At sexual maturity (two to four years old), male ostriches can be between 1.8 m and 2.7 m (6 feet and 9 feet) in height, while female ostriches range from 1.7 m to 2 m (5.5 ft to 6.5 ft). During the first year of life, chicks grow about 25 cm (10 inches) per month. At one year, ostriches weigh around 45 kg (100 pounds). An ostrich can live up to 75 years.

Systematics and distribution

The ostrich belong to the Struthioniformes order ( ratites). Other members of this group include rheas, emus, cassowaries and the largest bird ever, the now-extinct Aepyornis. However, the classification of the ratites as a single order has always being questioned, with the alternative classification restricting the Struthioniformes to the ostrich lineage and elevating the other groups to order status also. Presently, molecular evidence is equivocal while paleobiogeographical and paleontological considerations are slightly in favour of the multi-order arrangement.

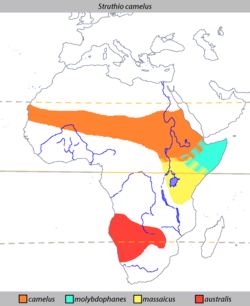

Ostriches occur naturally in the savannas and the Sahel of Africa, both north and south of the equatorial forest zone. Five subspecies are recognized:

- S. c. australis in Southern Africa

- S. c. camelus in North Africa, sometimes called the North African ostrich or red-necked ostrich.

- S. c. massaicus in East Africa, sometimes called the Masai ostrich. During the mating season, the male's neck and thighs turn pink-orange. Their range is from Ethiopia and Kenya in the east to Senegal in the west, and from eastern Mauritania in the north to southern Morocco in the south.

- S. c. syriacus in the Middle East, sometimes called the Arabian ostrich or Middle Eastern ostrich, was a subspecies formerly very common in the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Iraq; it became extinct around 1966.

- S. c. molybdophanes in Somalia, Ethiopia, and northern Kenya, is called the Somali ostrich. During the mating season, the male's neck and thighs turn blue. Its range overlaps with S.c. massaicus in northeastern Kenya.

Analyses indicate that the Somali ostrich may be better considered a full species. mtDNA haplotype comparisons suggest that it diverged from the other ostriches not quite 4 mya due to formation of the Great Rift Valley. Subsequently, hybridization with the subspecies that evolved southwestwards of its range, S. c. massaicus, has apparently been prevented to occur on a significant scale by ecological separation, the Somali ostrich preferring bushland where it browses middle-height vegetation for food while the Masai ostrich is, like the other subspecies, a grazing bird of the open savanna and miombo habitat (Freitag & Robinson, 1993).

The population from Río de Oro was once separated as Struthio camelus spatzi because its eggshell pores were shaped like a teardrop and not round, but as there is considerable variation of this character and there were no other differences between these birds and adjacent populations of S. c. camelus, it is not anymore considered valid. This population has disappeared in the later half of the 20th century. In addition, there have been 19th century reports of the existence of small ostriches in North Africa; these have been referred to as Levaillant's Ostrich (Struthio bidactylus) but remain a hypothetical form not supported by material evidence (Fuller, 2000). Given the persistence of savanna wildlife in a few mountaineous regions of the Sahara (such as the Tagant Plateau and the Ennedi Plateau), it is not at all unlikely that ostriches too were able to persist in some numbers until recent times after the drying-up of the Sahara.

Evolution

The earliest fossil of ostrich-like birds is the Central European Palaeotis from the Middle Eocene, a middle-sized flightless bird that was originally believed to be a bustard. Its distribution indicates that its ancestors must have flown across the ocean which at that time separated the continents from each other, and this indicates that theories about evolution and dispersal of the ratites need much more research before a consensus can be reached. Apart from this enigmatic bird, the fossil record of the ostriches continues with several species of the modern genus Struthio which are known from the Early Miocene onwards. While the relationship of the African species is comparatively straightforward, a large number of Asian species of ostrich have been described from very fragmentary remains, and their interrelationships and how they relate to the African ostriches is very confusing. In China, ostriches are known to have become extinct only around or even after the end of the last ice age; images of ostriches have been found there on prehistoric pottery and as petroglyphs. There are also records in maritime history of ostriches being sighted way out at sea in the Indian Ocean and when discovered on the island of Madagascar the sailors of the 18th century referred to them as Sea Ostriches, although this has never been confirmed.

Several of these fossil forms are ichnotaxa and their association with those described from distinctive bones is contentious and in need of revision pending more good material (Bibi et al., 2006).

- Struthio coppensi (Early Miocene of Elizabethfeld, Namibia)

- Struthio linxiaensis (Liushu Late Miocene of Yangwapuzijifang, China)

- Struthio orlovi (Late Miocene of Moldavia)

- Struthio karingarabensis (Late Miocene - Early Pliocene of SW and CE Africa) - oospecies(?)

- Struthio kakesiensis (Laetolil Early Pliocene of Laetoli, Tanzania) - oospecies

- Struthio wimani (Early Pliocene of China and Mongolia)

- Struthio daberasensis (Early - Middle Pliocene of Namibia) - oospecies

- Struthio brachydactylus (Pliocene of Ukraine)

- Struthio chersonensis (Pliocene of SE Europe to WC Asia) - oospecies

- Asian Ostrich, Struthio asiaticus (Early Pliocene - Late Pleistocene of Central Asia to China)

- Struthio oldawayi (Early Pleistocene of Tanzania) - probably subspecies of S. camelus

- Struthio anderssoni - oospecies(?)

Behaviour

Ostriches live in nomadic groups of 5 to 50 birds that often travel together with other grazing animals, such as zebras or antelopes. They mainly feed on seeds and other plant matter; occasionally they also eat insects such as locusts. Lacking teeth, they swallow pebbles that help as gastroliths to grind the swallowed foodstuff in the gizzard. An adult ostrich typically carries about 1 kg of stones in its stomach. Ostriches can go without water for a long time, exclusively living off the moisture in the ingested plants. However, they enjoy water and frequently take baths.

With their acute eyesight and hearing, they can sense predators such as lions from far away.

In popular mythology, the ostrich is famous for hiding its head in the sand at the first sign of danger. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder is noted for his descriptions of the ostrich in his Naturalis Historia, where he describes the ostrich and the fact that it hides its head in a bush. There have been no recorded observations of this behavior. A common counter-argument is that a species that displayed this behaviour would not likely survive very long. The myth may have resulted from the fact that, from a distance, when ostriches feed they appear to be burying their head in the sand because they deliberately swallow sand and pebbles to help grind up their food. Burying their heads in sand will in fact suffocate the ostrich. When lying down and hiding from predators, the birds are known to lay their head and neck flat on the ground, making them appear as a mound of earth from a distance. This even works for the males, as they hold their wings and tail low so that the heat haze of the hot, dry air that often occurs in their habitat aids in making them appear as a nondescript dark lump. When threatened, ostriches run away, but they can also seriously injure with kicks from their powerful legs.

The ostrich's behaviour is also mentioned in what is thought to be the most ancient book of the Bible in God's discourse to Job ( Job 39.13-18). It is described as joyfully proud of its small wings, unmindful of the safety of its nest, treats its offspring harshly, lacks in wisdom, yet can put a horse to shame with its speed. Elsewhere, ostriches are mentioned as proverbial examples of bad parenting (see Arabian Ostrich for details).

Ostriches are known to eat almost anything ( dietary indiscretion), particularly in captivity where opportunity is increased.

Ostriches can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. In much of its habitat temperature differences of 40°C between night- and daytime can be encountered. Their temperature control mechanism is more complex than in other birds and mammals, utilizing the naked skin of the upper legs and flanks (see the photo of the "dancing" female ostrich below) which can be covered by the wing feathers or bared according to whether the bird wants to retain or lose body heat.

Reproduction

Ostriches become sexually mature when 2 to 4 years old; females mature about six months earlier than males. The species is iteroparous, with the mating season beginning in March or April and ending sometime before September. The mating process differs in different geographical regions. Territorial males will typically use hisses and other sounds to fight for a harem of 2 to 5 females (which are called hens). The winner of these fights will breed with all the females in an area but only form a pair bond with one, the dominant female. The female crouches on the ground and is mounted from behind by the male.

Ostriches are oviparous. The females will lay their fertilized eggs in a single communal nest, a simple pit scraped in the ground and 30 to 60 cm deep. Ostrich eggs can weigh 1.3 kg and are the largest of all eggs, though they are actually the smallest eggs relative to the size of the bird. The nest may contain 15 to 60 eggs, with an average egg being 6 inches (15 cm) long, 5 inches (13 cm) wide, and weigh 3 pounds (1.4 kg). They are shiny and whitish in colour. The eggs are incubated by the females by day and by the male by night, making use of the different colors of the two sexes to escape detection. The gestation period is 35 to 45 days. Typically, the male will tend to the hatchlings.

The life span of an ostrich can extend from 30 to 70 years, with 50 being typical.

Ostriches and humans

In the past, ostriches were mostly hunted and farmed for their feathers, which used to be very popular as ornaments in ladies' hats and such. Their skins were also valued to make a fine leather. In the 18th century, they were almost hunted to extinction; farming for feathers began in the 19th century. The market for feathers collapsed after World War I, but commercial farming for feathers and later for skins, took off during the 1970s.

The Arabian Ostriches in the Near and Middle East were hunted to extinction by the middle of the 20th century.

Today, ostriches are bred all over the world, including climates as cold as that of Sweden. They will prosper in climates between 30 and −30 °C, and are farmed in over 50 countries around the world, but the majority are still found in Southern Africa. Since they also have the best feed to weight ratio gain of any land animal in the world (3.5:1 whereas that of cattle is 6:1), they are bound to appear attractive to farmers. Although they are farmed primarily for leather and secondarily for meat, additional useful byproducts are the eggs, offal, and feathers. It is traditional to place seven of the large eggs on the roof of an Ethiopian Orthodox church, to symbolise the Heavenly and Earthly Angels.

It is claimed that ostriches produce the strongest commercially available leather1. Ostrich meat tastes similar to lean beef and is low in fat and cholesterol, as well as high in calcium, protein and iron.

Ostriches are large enough for a small human to ride them; typically, the human will hold on to the wings while riding. They have been trained in some areas of northern Africa and Arabia as racing mounts. Ostrich races in the United States have been criticized by animal rights organizations, however there is little possibility of this becoming a widespread practice due to the fact that the animals are difficult to saddle (and ostriches are known to have a rather irascible temper).

Ostriches are classified as dangerous animals in Australia, the US and the UK. There are a number of recorded incidents of people being attacked and killed. Big males can be very territorial and aggressive and can attack and kick very powerfully with their legs. An ostrich will easily outrun any human athlete. Their legs are powerful enough to eviscerate large animals.

Ostrich farming

The town of Oudtshoorn in South Africa has the world's largest population of ostriches. Many farms and specialized breeding centres have been set up around the town such as the Safari Show Farm and the Highgate Ostrich Show Farm. The CP Nel Museum is a museum that specializes in the history of the ostrich.

Gallery

|

Ostrich eggs for sale in a Polish supermarket. |

|||

|

Male and female ostriches on a farm in New Zealand. |