Spanish Armada

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500-1750

| Battle of Gravelines | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

Defeat of the Spanish Armada, 1588- 08-08 by Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, painted 1797, depicts the battle of Gravelines. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| England Dutch Republic |

Spain Portugal |

||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Charles Howard Francis Drake |

Duke of Medina Sidonia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 34 warships 163 merchant vessels |

22 galleons 108 merchant vessels |

||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 50–100 dead ~400 wounded |

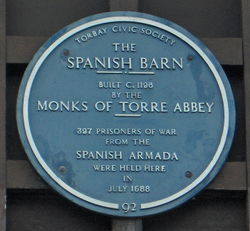

600 dead, 800 wounded, 397 captured, 4 merchant ships sunk or captured |

||||||

| Anglo-Spanish War |

|---|

| San Juan de Ulúa – Gravelines – Corunna – Lisbon – Spanish Main – Azores |

The Spanish Armada (Old Spanish: Grande y Felicísima Armada, "Great and Most Fortunate Navy," but called by the English, with ironic intention, the "Invincible Fleet") was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of the Duke of Medina Sedonia in 1588. The Armada was sent by the Catholic King Philip II of Spain, who had, until the death of his wife Mary I of England, been king consort of England. The purpose of the operation was to escort the Duke of Parma's fearsome Spanish tercios from the Spanish Netherlands across the North Sea for a landing in south-east England. The aim was to suppress English support for the United Provinces, formerly part of the Spanish Netherlands. Further aims were to cut off attacks against the Spanish possessions in the New World and the Atlantic treasure fleets, and to re-establish England (then ruled by the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I) as a Roman Catholic kingdom. The expedition was supported by the Pope, and proved the largest engagement of the undeclared Anglo–Spanish War ( 1585– 1604).

The Armada consisted of 130 warships and converted merchant ships and faced an English fleet of about 200 vessels. After forcing its way up the Channel, the Armada was attacked by English naval squadrons, with the assistance of the Dutch navy, at the Battle of Gravelines in the North Sea, off the coastal border between France and the Spanish Netherlands. A fire-ship attack drove Medina Sedonia's ships from their anchorage, and the Spanish were then forced to abandon their rendezvous with the invasion army in the face of superior English artillery.

The Armada was blown north up the east coast of England and attempted a return to Spain by sailing around Scotland and out into the Atlantic, past Ireland. But very severe weather destroyed a portion of the fleet, and more than 24 vessels were wrecked on the north and western coasts of Ireland, with the survivors having to seek refuge in Scotland. Of the Armada's initial complement of vessels, about 50 did not return to Spain. However, the loss to Philip's Royal Navy was comparatively small: only seven ships failed to return, and of these only three were lost to enemy action.

The battle is greatly misunderstood, as many myths have surrounded it. English writers have tended to present it as a pivotal moment in European history, which is to ignore the fact that it marked the beginning of an increase in Spanish naval supremacy, rather than a long decline.

Execution

On May 28, 1588, the Armada, with around 130 ships, 8,000 sailors and 18,000 soldiers, 7,000 sailors, 1,500 brass guns and 1,000 iron guns, set sail from Lisbon in Portugal, headed for the English Channel. An army of 30,000 men stood in the Spanish Netherlands, waiting for the fleet to arrive. The plan was to land the original force in Plymouth and transfer the land army to somewhere near London, mustering 55,000 men, a huge army for this time. The English fleet was prepared and waiting in Plymouth for news of Spanish movements. It took until May 30 for all of the Armada to leave port and, on the same day, Elizabeth's ambassador in the Netherlands, Dr Valentine Dale, met Parma's representatives to begin peace negotiations. On July 17 negotiations were abandoned because of a fight over a bowl of soup.

Delayed by bad weather, the Armada was not sighted in England until July 19, when it appeared off The Lizard in Cornwall. The news was conveyed to London by a sequence of beacons that had been constructed the length of the south coast of England. That same night, 55 ships of the English fleet set out in pursuit from Plymouth and came under the command of Lord Howard of Effingham (later Earl of Nottingham) and Sir John Hawkins. However, Hawkins acknowledged his subordinate, Sir Francis Drake, as the more experienced naval commander and gave him some control during the campaign. In order to execute their "line ahead" attack, the English tacked upwind of the Armada, thus gaining a significant manoeuvring advantage.

Over the next week there followed two inconclusive engagements, at Eddystone and Portland, Dorset. At the Isle of Wight the Armada had the opportunity to create a temporary base in protected waters and wait for word from Parma's army. In a full-on attack, the English fleet broke into four groups with Drake coming in with a large force from the south. At that critical moment, Medina Sidonia sent reinforcements south and ordered the Armada back into the open sea in order to avoid sandbanks. This left two Spanish wrecks, and with no secure harbours nearby the Armada sailed on to Calais, without regard to the readiness of Parma's army.

On July 27, the Spanish anchored off Calais, not far from Parma's waiting army of 16,000 in Dunkirk, in a crescent-shaped, tightly-packed defensive formation. There was no deep-water port along that coast of France and the Low Countries where the fleet might shelter - always a major difficulty for the expedition - and the Spanish found themselves vulnerable as night drew on.

At midnight of July 28, the English set eight fireships (filled with pitch, gunpowder, and tar) alight and sent them downwind among the closely-anchored Spanish vessels. The Spaniards feared that these might prove as deadly as the ' hell burners' used against them to deadly effect at the Siege of Antwerp. Two were intercepted and towed away, but the others bore down on the fleet. Medina Sedonia's flagship, and a few other "core" ships, held their positions, but the rest of the fleet cut their cables and scattered in confusion, with the result that only one Spanish ship was burned. But the fireships had managed to break the crescent formation, and the fleet now found itself too far to leeward of Calais in the rising south-westerly wind to recover its position. The lighter English ships then closed in for battle at Gravelines.

Battle of Gravelines

Gravelines was part of Flanders in the Spanish Netherlands, close to the border with France and the closest Spanish territory to England. Medina-Sidonia tried to re-form his fleet there, and was reluctant to sail further east owing to the danger from the shoals off Flanders, from which his Dutch enemies had removed the sea-marks. The Spanish army had been expected to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast, but communications were far more difficult than anticipated, and without notice of the Armada's arrival Parma needed another six days to bring his troops up, while Medina-Sidonia waited at anchor.

The English had learned much of the Armada's strengths and weaknesses during the skirmishes in the English Channel, and accordingly conserved their heavy shot and powder prior to their attack at Gravelines on July 29. During the battle, the Spanish heavy guns proved unwieldy, and their gunners hadn't been trained to re-load - in contrast to their English counterparts, they fired once and then jumped to the rigging to attend to their main task as marines ready to board enemy ships. Evidence from wrecks in Ireland shows that much of the Armada's ammunition was never spent.

In 2002 Dr Colin Martin of the University of St Andrews claimed that many Spanish ships carried cannon shot that was the wrong size for their cannon. The equipment had been gathered from a wide variety of sources in the Spanish Habsburg lands which were world-wide and, in Europe, scattered between the Heel of Italy, southern Portugal and the Ems estuary. The notion of standardization had barely been explored at this stage.

With its superior maneuverability, the English fleet provoked Spanish fire while staying out of range. Once the Spanish had loosed their heavy shot, the English then closed, firing repeated and damaging broadsides into the enemy ships. This superiority also enabled them to maintain a position to windward so that the heeling Armada hulls were exposed to damage below the water-line.

The main handicap for the Spanish was their determination to board the enemy's ships and thrash out a victory in hand-to-hand fighting. This had proved effective at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, but the English were aware of this Spanish strength and avoided it through their superiority in artillery and maneuverability.

Eleven Spanish ships were lost or damaged (though the most seaworthy Atlantic-class vessels escaped largely unscathed). The Armada suffered nearly 2,000 battle casualties, before the English fleet ran out of ammunition. English casualties in the battle were far fewer, in the low hundreds. The Spanish plan to join with Parma's army had been defeated, and the English had afforded themselves some breathing space. But the Armada's presence in northern waters still posed a great threat to England.

Pursuit

On the day after Gravelines, the wind had backed, southerly, enabling Medina Sidonia to move the Armada northward (away from the French coast). Although their shot lockers were almost empty, the English pursued and harried the Spanish fleet, in an attempt to prevent it returning to escort Parma. On 12 August, Howard called a halt to the chase in the latitude of the Firth of Forth off Scotland. But by that point, the Spanish were suffering from thirst and exhaustion. The only option left to Medina Sidonia was to chart a course home to Spain, along the most hazardous parts of the Atlantic seaboard.

Tilbury speech

The threat of invasion from the Netherlands had not yet been discounted, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester maintained a force of 4,000 soldiers at Tilbury Fort, Essex, to defend the estuary of the River Thames against any incursion up-river towards London.

On August 8, Elizabeth went to Tilbury to encourage her forces, and the next day gave to them what is probably her most famous speech:

I have come amongst you as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved in the midst and heat of the battle to live or die amongst you all, to lay down for my God and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too....

The return to Spain

The Spanish fleet sailed around Scotland and Ireland into the North Atlantic. The ships were beginning to show wear from the long voyage, and some were kept together by having their hulls bundled up with cables. Supplies of food and water ran short, and the cavalry horses were driven overboard into the sea. Shortly after reaching the latitude of Ireland, the Armada ran straight into a hurricane—to this day, it remains one of the northernmost on record. The hurricane scattered the fleet and drove some two dozen vessels onto the coast of Ireland. (See Protestant Wind)

A new theory suggests that the Spanish fleet failed to account for the effect of the Gulf Stream. Therefore they were much closer to Ireland than planned, a devastating navigational error. This was during the " Little Ice Age" and the Spanish were not aware that conditions were far colder and more difficult than they had expected for their trip around the north of England and Ireland. As a result many more ships and sailors were lost to cold and stormy weather than in combat actions.

Following the storm, it is reckoned that 5,000 men died, whether by drowning and starvation or by execution at the hands of English forces in Ireland. The reports from Ireland abound with strange accounts of brutality and survival, and attest on occasion to the brilliance of Spanish seamanship. Survivors did receive help from the Gaelic Irish, with many escaping to Scotland and beyond.

In the end, 67 ships and around 10,000 men survived. Many of the men were near death from disease, as the conditions were very cramped and most of the ships ran out of food and water. Many more died in Spain, or on hospital ships in Spanish harbours, from diseases contracted during the voyage. It was reported that, when Philip II learned of the result of the expedition, he declared, "I sent my ships to fight against the English, not against the elements".

Consequences

English losses were comparatively few, and none of their ships were sunk. But after the victory, typhus and dysentery killed many sailors and troops (estimated at 6,000–8,000) as they languished for weeks in readiness for the Armada's return out of the North Sea. Then a demoralising dispute occasioned by the government's fiscal shortfalls left many of the Armada defenders unpaid for months, which was in contrast to the assistance given by the Spanish government to its surviving men.

Although the victory was acclaimed by the English as their greatest since Agincourt, an attempt in the following year to press home their advantage failed, when an English Armada returned to port with little to show for its efforts. But the boost to national pride lasted for years, and Elizabeth's legend persisted and grew well after her death. The repulse of Spanish naval might gave heart to the Protestant cause across Europe. High seas buccaneering against the Spanish persisted, and the supply of troops and munitions from England to Philip II's enemies in the Netherlands and France continued, but the Anglo-Spanish war thereafter generally favoured Spain.

It was half a century later when the Dutch finally decisively broke Spain's dominance at sea in the Battle of the Downs in (1639). The strength of its tercios, the dominant fighting unit in European land campaigns for over a century, was broken by the French at the Battle of Rocroi (1643). Two further wars between England and Spain were waged in the 17th Century, but it was only during the Napoleonic Wars that the British navy, increasingly dominant in the 18th century, established its overwhelming mastery at sea, at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Ships involved

England and the Netherlands

Ark Royal (built as 'Ark Raleigh' bought by Elizabeth I and renamed) (flag, Lord High Admiral Charles Howard)

Elizabeth Bonaventure ( George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland)

Rainbow ( Lord Henry Seymour)

Golden Lion ( Lord Thomas Howard)

White Bear (Alexander Gibson)

Vanguard (William Winter)

Revenge (Francis Drake)

Elizabeth (Robert Southwell)

Victory (Rear Admiral Sir John Hawkins)

Antelope (Henry Palmer)

Triumph ( Martin Frobisher)

Dreadnought (George Beeston)

Mary Rose (Edward Fenton)

Nonpareil (Thomas Fenner)

Hope (Robert Crosse)

Galley Bonavolia

Swiftsure (Edward Fenner)

Swallow (Richard Hawkins)

Foresight

Aid

Bull

Tiger

Tramontana

Scout

Achates

Charles

Moon

Advice

Merlin

Spy (pinnace)

Sun (pinnace)

Cygnet

Brigandine

George (hoy)

34 merchant ships

30 ships and barks

33 ships and barks

20 coasters

23 coasters

23 coasters

Disdain (included in above)

Margaret and John (included in above)

30 Dutch cromsters blockading the Flemish coast

Fireships expended 7 August: (included in above)

Bark Talbot

Hope

Thomas

Bark Bond

Bear Yonge

Elizabeth

Angel

"Cure's Ship"

Spain and Portugal

Portuguese

São Martinho 48 (section flag, Duke of Medina Sidonia)

São João 50 (section vice-flag)

São Marcos 33 (Don Diogo Pimental or Penafiel) — Aground c. 8 August near Ostend

São Felipe 40 (Don Francisco de Toledo) — Aground 8 August between Nieupoort and Ostend, captured by Dutch 9 August

San Luis 38

San Mateo 34 — Aground 8 August between Nieupoort and Ostend, captured by Dutch 9 August

Santiago 24

Galeon de Florencia 52 (or San Francesco ex-Levantine, Niccolo Bartoli)

San Crístobal 20

San Bernardo 21

Augusta 13

Julia 14

Biscayan

Santa Ana 30 (section flag, Juan Martínez de Recalde)

El Gran Grin 28 (section vice-flag) — Aground c. 24 September, Clare Island

Santiago 25

La Concepcion de Zubelzu 16

La Concepcion de Juan del Cano 18

La Magdalena 18

San Juan 21

La María Juan 24 — Sunk 8 August north of Gravelines

La Manuela 12

Santa María de Montemayor 18

María de Aguirre 6

Isabela 10

Patache de Miguel de Suso 6

San Esteban 6

Castilian

San Crístobal 36 (section flag, Diego Flores de Valdés)

San Juan Bautista 24 (section vice-flag)

San Pedro 24

San Juan 24

Santiago el Mayor 24

San Felipe y Santiago 24

La Asuncion 24

Nuestra Señora del Barrio 24

San Linda y Celedon 24

Santa Ana 24

Nuestra Señora de Begoña 24

La Trinidad Bogitar 24

Santa Catalina 24

San Juan Bautista 24

Nuestra Señora del Rosario 24

San Antonio de Padua 12

Guipúzcoan

Santa Ana 47 (section flag, Miguel de Oquendo)

Santa María de la Rosa 26 (section vice-flag) — Damaged 8 August, wrecked 16 September, Blaskett Sound, Ireland

San Salvador 25 — Damaged by explosion and captured c. 31 July

San Esteban 26 — Wrecked 20 September, Ireland

Santa Marta 20

Santa Bárbara 12

San Buenaventura 21

La María San Juan 12

Santa Cruz 18

Doncella 16 — Sank at Santander after returning to Spain

Asuncion 9

San Bernabe 9

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe 1

La Madalena 1 " Reberto Dunecan

Levant

La Regazona lgonio 30 (section flag, Martín de Bertandona)

La Lavia 25 (section vice-flag)

La Rata Santa María Encoronada 35 (Leiva)

San Juan de Sicilia 26 (formerly Brod Martolosi) — Blew up (possibly sabotage from English agent) 5 November Tobermory Bay, Scotland

La Trinidad Valencera 42 — aground 8 August

La Anunciada 24 (formerly Presveta Anuncijata) — Scuttled 19 September at Shannon River mouth

San Nicolas Prodaneli 26 (formerly Sveti Nikola)

La Juliana 32

Santa María de Vison 18

La Trinidad de Scala 22

Hulks

El Gran Grifón pogitor 38 (section flag, Juan Gómez de Medina) — Aground 8 August

San Salvador 24 (section vice-flag)

Perro Marino 7

Falcon Blanco Mayor 16

Castillo Negro 27

Barca de Amburg 23 — sank

Casa de Paz Grande 26

San Pedro Mayor 29

El Sanson 18

San Pedro Menor 18

Barca de Danzig 26

Falcon Blanco Mediano 16 (Don Luis de Cordoba?) — Wrecked c. 25 September

San Andres 14

Casa de Paz Chica 15

Ciervo Volante 18

Paloma Blanca 12

La Ventura 4

Santa Bárbara 10

Santiago 19

David 7

El Gato 9

San Gabriel 4

Esayas 4

Neapolitan galleasses

San Lorenzo 50 (Don Hugo de Moncado) — Aground, captured 8 August, distracting the English fleet

Zúñiga 50

Girona 50 — Wrecked in Ulster

Napolitana ("Patrona") 50

Bazana - Wrecked c. 26 July near Bayonne

22 pataches and zabras (Don Antonio Hurtado de Medoza)

4 galleys of 5 guns each (Diego de Medrano)

vessels under Parma

Other meanings

- Spanish Armada ( Armada Española) can also describe the modern navy of Spain, part of the Spanish armed forces. The Spanish navy has participated in a number of military engagements, including the dispute over the Isla Perejil. This is not a reference to the Armada above — "armada" simply means "navy" in Spanish.

- In Tennis slang, Spanish Armada is used to refer to the group of highly ranked Spanish players, such as Felix Mantilla, Albert Portas, Juan Carlos Ferrero, Carlos Moyá, and others.