Recorder

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Musical Instruments

The recorder is a woodwind musical instrument of the family known as fipple flutes or internal duct flutes—whistle-like instruments which include the tin whistle and ocarina. The recorder is end-blown and the mouth of the instrument is constricted by a wooden plug, known as a block or fipple. It is distinguished from other members of the family by having holes for seven fingers (the lower one or two often doubled to facilitate the production of semitones) and one for the thumb of the uppermost hand. The bore of the recorder is occasionally cylindrical but is usually tapered slightly, being widest at the mouthpiece end.

The recorder was popular from mediaeval times but declined in the eighteenth century in favour of orchestral woodwind instruments, such as the flute and possibly the clarinet, which have greater chromatic range and louder volume. During its heyday, the recorder was traditionally associated with birds, shepherds, miraculous events, funerals, marriages and amorous scenes. Images of recorders can be found in literature and artwork associated with all these. Purcell, Bach, Telemann and Vivaldi used the recorder to suggest shepherds and birds, and the pattern continued into the 20th Century.

The recorder was revived in the twentieth century, partly in the pursuit of historically informed performance of early music, but also because of its suitability as a simple instrument for teaching music and its appeal to amateur players. Today, it is often thought of as a child's instrument, but there are many excellent virtuosic players who can demonstrate the instrument's full potential as a solo instrument. The sound of the recorder is remarkably clear and sweet, partly because of the lack of upper harmonics and predominance of odd harmonics in the sound.

In German the recorder is called the Blockflöte (Block Flute), in French the flûte à bec (Beaked Flute), in Italian the flauto dolce (Sweet Flute), in Spanish the flauta de pico (beak Flute), and in contemporary music blockflute. The English name may come from a Middle English use of the word record, meaning, "to practice a piece of music".

How the instrument is played

Click here to hear a soprano (descant) recorder being played.

The recorder is held outwards from the player's lips (rather than to the side, like the "transverse" flute). The player's breath is constrained by a wooden "block" (A), in the mouthpiece of the instrument, so as to travel along a duct (B) called the "windway". Exiting from the windway, the breath is directed against a hard edge (C), called the " labium", which agitates a column of air, the length of which (and the pitch of the note produced) is modified by finger holes in the front and back of the instrument. The roughly rectangular opening in the top of the recorder, adjacent to the labium is called the "window". Because of the fixed position of the windway with respect to the labium, the embouchure does not depend on the lips; instead, the shape and size of the recorder player's mouth cavity has a discernable effect on the timbre, tone and response of the recorder—indeed, much of the skill of recorder playing is concerned with using the parts of the mouth (as well as the diaphragm) to shape and control the stream of air entering the recorder.

The range of a recorder is about two octaves. A skilled player can extend this and can typically play chromatically over two octaves and a fifth. The note two octaves and one semitone above the lowest note (C# for soprano, tenor and great bass instruments: F# for sopranino, alto and bass instruments) can normally only be played by covering the end of the instrument, typically by using one's upper leg or a special bell key. The note is only occasionally found in pre-20th-century music, but it has become standard in modern music. Use of other notes in the 3rd octave is becoming more common, several requiring closure of the bell or shading of the window area (ie holding a finger above the window, partially restricting the air emerging from it). In the hands of a competent player, these upper notes are not especially loud or shrill.

The lowest chromatic scale degrees— the minor second and minor third above the lowest note — are played by covering only a part of a hole, a technique known as "half-holing." Most modern instruments are constructed with double holes or keys to facilitate the playing of these notes. Other chromatic scale degrees are played by so-called "fork" fingerings, uncovering one hole and covering one or more of the ones below it. Fork fingerings have a different tonal character from the diatonic notes, giving the recorder a somewhat uneven sound. Many "budget" tenor recorders have a single key for low C but not low C#, making this note virtually impossible. Other tenor recorder producers, more aware of this dilemma, produce an instrument with a double low key, allowing both C and C#.

Most of the notes in the second octave and above are produced by partially closing the thumbhole on the back of the recorder, a technique known as 'pinching'. The placement of the thumb is crucial to the intonation and stability of these notes, and varies as the notes increase in pitch, making the boring of a double hole for the thumb unviable.

History

Early Recorders

Internal duct-flutes have a long history: an example of an Iron Age specimen, made from a sheep bone, exists in Leeds City Museum.

The true recorders are distinguished from other internal duct flutes by having eight finger holes; seven on the front of the instrument and one, for the left hand thumb, on the back, and having a slightly tapered bore, with its widest end at the mouthpiece. It is thought that these instruments evolved in the 14th century, but an earlier origin is a matter of some debate, based on the depiction of various whistles in medieval paintings. To this day whistles -as used in Irish folk music- have six holes. The original design of the transverse flute (and its fingering) was based on the same six holes, but it was later much altered by Theobald Böhm.

One of the earliest surviving instruments was discovered in a castle moat in Dordrecht, the Netherlands in 1940, and has been dated to the 14th century. It is, however, in very poor condition. A second damaged 14th century recorder was found in a latrine in northern Germany (in Göttingen): other 14th-century examples survive from Esslingen (Germany) and Tartu (Estonia), and there is a fragment of a possible 14th-15th-century bone recorder at Rhodes (Greece).

The Renaissance

The recorder achieved great popularity in the 16th and 17th centuries. This development was linked to the fact that art music (as opposed to folk music) was no longer the exclusive domain of nobility and clergy. The advent of the printing press made it available to the more affluent commoners as well. The popularity of the instrument also reached the courts however. For example, at Henry VIII's death in 1547, an inventory of his possessions included 76 recorders. There are also numerous references to the instrument in contemporary literature (eg Shakespeare, Pepys and Milton). Many instruments survive from this period, including an incomplete set of recorders in Nuremberg which date from the 16th century and are still in a playable condition.

Renaissance recorders sound somewhat different to the modern recorders, largely owing to their wider, less tapered bore. The sound is louder, especially in the lower notes, and can be described as "fuller" or "woodier". The wide bore means that greater air pressure is required to play the instrument, but this makes them more responsive. They can usually only be played reliably over a range of an octave and a sixth.

Baroque Recorders

Several changes in the construction of recorders took place in the seventeenth century, resulting in the type of instrument generally referred to as baroque recorders, as opposed to the earlier renaissance recorders. These innovations allowed baroque recorders to play two full chromatic octaves of notes, and to possess a tone which was regarded as "sweeter" than that of the earlier instruments.

In the 18th century, rather confusingly, the instrument was often referred to simply as Flute (Flauto) — the transverse form was separately referred to as Traverso. In the 4th Brandenburg Concerto in G major, J.S. Bach calls for two "flauti d'echo". The musicologist Thurston Dart mistakenly suggested that it was intended for flageolets at a higher pitch, and in a recording under Neville Marriner using Dart's editions it was played an octave higher than usual on sopranino recorders. An argument can be made that the instruments Bach identified as "flauti d'echo" were echo flutes, an example of which survives in Leipzig to this day. It consisted of two recorders in f' connected together by leather flanges: one instrument was voiced to play softly, the other loudly. Vivaldi wrote three concertos for the "flautino" and required the same instrument in his opera orchestra. In modern performance, the "flautino" was initially thought to be the piccolo. It is now generally accepted, however, that the instrument intended was a recorder with lowest note d5.

The decline of the recorder

The instrument went into decline after the 18th century, being used for about the last time as an other-worldly sound by Gluck in his opera Orfeo ed Euridice.

By the Romantic era, the recorder had been almost entirely superseded by the flute and clarinet. Nonetheless there were probably more works (ca 800) written for the recorder during the 19th century than in all the preceding centuries: the instrument simply sprouted keys and changed its name, being known as the csakan or "flute douce".

Modern revival

The recorder was revived around the turn of the 20th Century by early music enthusiasts, but used almost exclusively for this purpose. It was considered a mainly historical instrument. Even in the early 20th century it was uncommon enough that Stravinsky thought it to be a kind of clarinet, which is not surprising since the early clarinet was, in a sense, derived from the recorder, at least in its outward appearance.

The eventual success of the recorder in the modern era is often attributed to Arnold Dolmetsch in the UK and various German scholar/performers. Whilst he was responsible for broadening interest beyond that of the early music specialist in the UK, Dolmetsch was far from being solely responsible for the recorder's revival. On the Continent his efforts were preceded by those of musicians at the Brussels Conservatoire (where Dolmetsch received his training), and by the performances of the Bogenhausen Künstlerkapelle (Bogenhausen Artists' Band) based in Germany. Over the period from 1890-1939 the Bogenhausers played music of all ages, including arrangements of classical and romantic music. Also in Germany, the work of Willibald Gurlitt, Werner Danckerts and Gustav Scheck proceded quite independently of the Dolmetsches.

In the mid 20th Century, manufacturers were able to make recorders out of bakelite and (more successfully) plastics which made them cheap and quick to produce. Because of this, recorders became very popular in schools, as they are one of the cheapest instruments to buy in bulk. They are also relatively easy to play at a basic level as they are pre-tuned, and are not too strident in even the most musically-inept hands. It is, however, incorrect to assume that mastery is similarly easy — like other instruments, the recorder requires talent and study to play at an advanced level.

The success of the recorder in schools is partly responsible for its poor reputation as a "child's instrument". Although the recorder is ready-tuned, it is very easy to warp the pitch by over or under blowing, which often results in an unpleasant sound from beginners.

Among the influential virtuosos who figure in the revival of the recorder as a serious concert instrument in the latter part of the twentieth century are Frans Brüggen, Hans-Martin Linde, Bernard Kranis, and David Munrow. Brüggen recorded most of the landmarks of the historical repertoire and commissioned a substantial number of new works for the recorder. Munrow's 1975 double album The Art of the Recorder remains as an important anthology of recorder music through the ages.

Modern composers of great stature have written for the recorder, including Paul Hindemith, Luciano Berio, John Tavener, Michael Tippett, Benjamin Britten, Leonard Bernstein, Gordon Jacob, and Edmund Rubbra.

It is also occasionally used in popular music, including that of groups such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and Jimi Hendrix.

Some modern music calls for the recorder to produce unusual noises, rhythms and effects, by such techniques as flutter-tongueing and overblowing to produce chords. David Murphy's 2002 composition Bavardage is an example, as is Hans Martin Linde's Music for a Bird.

Among modern recorder ensembles, the trio Sour Cream (led by Frans Brüggen), the Flanders Recorder Quartet and the Amsterdam Loeki Stardust Quartet have programmed remarkable mixtures of historical and contemporary repertoire.

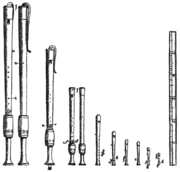

Types of recorder

Recorders are most often tuned in C and F, though instruments in D, G, and E-flat were not uncommon historically and are still found today, especially the tenor in D, known as a voice flute. The size most frequently used in classroom instruction is the soprano in C (in Britain also known as the descant) which has a lowest note of c'' (one octave above middle C). Above this are the sopranino in F and the gar klein Flötlein ("really small flute") or "garklein" in C, with a lowest note of c'''. An experimental 'piccolino' has also been produced in f''', but the garklein is already too small for adult-sized fingers to play easily. Below the soprano are the alto in F (in Britain also known as the treble), tenor in C, and bass in F. Lower instruments in C and F also exist: bass in C (in Britain also known as the great bass), contrabass in F, subcontrabass in C, and sub-subcontrabass or octo-contrabass in F, but these are more rare. They are also difficult to handle: the contrabass in F is about 2 meters tall. The soprano and the alto are the most common solo instruments in the recorder family.

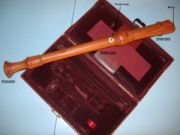

Today, high-quality recorders are made from a range of different hardwoods, such as oiled pear wood, rosewood or boxwood with a block of red cedar wood. However, many recorders are made of plastic, which is cheaper, is resistant to damage from condensation, and does not require re-oiling. While higher-end professional instruments are almost always wooden, many plastic recorders currently being produced are equal to or better than lower-end wooden instruments. Beginners' instruments, the sort usually found in children's ensembles, are also made of plastic and can be purchased quite cheaply.

Most modern recorders are based on instruments from the baroque period, although some specialist makers produce replicas of the earlier renaissance style of instrument. These latter instruments have a wider, less tapered bore and typically possess a loud and strident tone.

Some newer designs of recorder are now being produced. One area are square section larger instruments which are cheaper than the normal designs if, perhaps, not so elegant. Another area is the development of instruments with a greater dynamic range and more powerful bottom notes. These modern designs make it easier to be heard when playing concerti.

Makers

The evolution of the renaissance recorder into the baroque instrument is generally attributed to the Hottetere family, in France. They developed the ideas of a more tapered bore (allowing greater range) and the construction of instruments in several jointed sections. This innovation allowed more accurate shaping of each section and also offered the player minor tuning adjustments, by slightly pulling out one of the sections to lengthen the instrument.

The French innovations were taken to London by Pierre Bressan, a set of whose instruments survive in the Grosvenor Museum, Chester, as well as examples in other European museums. Bressan's contemporary, Thomas Stanesby, was born in Derbyshire but became an instrument maker in London. He and his son (Thomas Stanesby junior) were the other important British-based recorder-makers of the early eighteenth century.

In continental Europe, the Denner family of Nürnberg were the most celebrated makers of this period.

Many modern recorders are based on the dimensions and construction of surving instruments produced by Bressan, the Stanesbys or the Denner family.

Recorder ensembles

The recorder is a very social instrument. Many amateurs enjoy playing in large groups or in one-to-a-part chamber groups, and there is a wide variety of music for such groupings including many modern works. Groups of different sized instruments help to compensate for the limited note range of the individual instruments.

One of the more interesting developments in recorder playing over the last 30 years has been the development of recorder orchestras. They can have 60 or more players and use up to nine sizes of instrument. In addition to arrangements, many new pieces of music, including symphonies, have been written for these ensembles. There are recorder orchestras in Germany, Holland, Japan, The United States, Canada, and the UK.