Quetzalcoatl

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Divinities

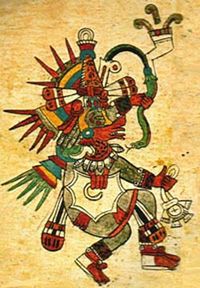

Quetzalcoatl ("feathered serpent" or "plumed serpent") is the Nahuatl name for the Feathered-Serpent deity of ancient Mesoamerican culture. In Mesoamerican myth Quetzalcoatl is also a mythical culture hero from whom almost all mesoamerican peoples claim descent. These myths often describe him as the a divine ruler of the mythical Toltecs of Tollan who after his expulsion from Tollan, travelled south or east to set up new cities and kingdoms. Many different Mesoamerican cultures, e.g. Maya, K'iche, Pipil, Zapotec claim to have been the only true lineage of Quetzalcoatl and thus of the mythical Toltecs.

Antecedents and origins

The name Quetzalcoatl literally means "feathered snake". The Nahuatl word quetzalli means "long green feather" (Molina: ), but later came to be applied also to the bird who give these feathers: the Resplendent Quetzal. Quetzal feathers were a rare and precious commodity in the Aztec culture. So the combination of quetzalli "precious feather" and coatl "snake" has often been interpreted as signifying a serpent with the feathers of Quetzal. The meaning of his local name in other Mesoamerican languages is similar. The Maya of Yucatán knew him as Kukulk'an; the K'iche-Maya of Guatemala, as Guk'umatz, both names can be translated as "feathersnake".

The Feathered Serpent deity was important in art and religion in most of Mesoamerica for close to 2,000 years, from the Pre-Classic era until the Spanish conquest. Civilizations worshipping the Feathered Serpent included the Olmec, Mixtec, Toltec, Aztec, who adopted it from the people of Teotihuacan, and the Maya.

The cult of the serpent in Mesoamerica is very old; there are representations of snakes with bird-like characteristics as old as the Olmec preclassic (1150-500 BC). The snake represents the earth and vegetation, but it was in Teotihuacan (around 150 BC) where the snake got the precious feathers of the Quetzal, as seen in the Murals of the city. The most elaborate representations come from the old Quetzalcoatl Temple built around 200 BC, which shows a rattlesnake with the long green feathers of the quetzal.

Teotihuacan was dedicated to Tlaloc, the water god, at the same time Quetzalcoatl, as a snake, was a representation of the fertility of the earth, and it was subordinate to Tlaloc. As the cult evolved, it became independent.

In time Quetzalcoatl was mixed with other gods, and acquired their attributes. Quetzalcoatl is often associated with Ehecatl, the wind god, and represents the forces of nature, and is also associated with the morning star (Venus). Quetzalcoatl became a representation of the rain, the celestial water and their associated winds, while Tlaloc would be the god of earthly water, the water in lakes, caverns and rivers, and also of vegetation. Eventually Quetzalcoatl was transformed into one of the gods of the creation (Ipalnemohuani).

The Teotihuacan influence took the god to the Mayas, who adopted him as Kukulkán. The Maya regarded him as a being who would transport the gods.

In Xochicalco (700-900 AD), the political class began to claim that they ruled in the name of Quetzalcoatl, and representations of the god became more human. They influenced the Toltec, and the Toltec rulers began to use the name of Quetzalcoatl. The Toltec represented Quetzalcoatl as man, with god-like attributes, and these attributes were also associated with their rulers.

The most famous of those rulers was Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl. Ce Acatl means "one reed" and is the calendaric name of the ruler (923 - 947), whose legends became almost inseparable from accounts of the god. The Toltecs would associate Quetzalcoatl with their own god, Tezcatlipoca, and make them equals, enemies and twins. The legends of Ce Acatl told us that he thought his face was ugly, so he let his beard grow to hide it, and eventually he wore a white mask. This legend has been distorted so representations of Quezalcoatl as a white bearded man have become common.

The Nahuas would take the legends of Quetzalcoatl and mix them with their own. Quetzalcoatl would be considered the originator of the arts, poetry and all knowledge. The figure of Ce Acatl would become inseparable from the image of the god.

Religion and Ritual

The worship of Quetzalcoatl sometimes included animal sacrifices, and in other traditions Quetzalcoatl was said to oppose human sacrifice.

Mesoamerican priests and kings would sometimes take the name of a deity they were associated with, so Quetzalcoatl and Kukulcan are also the names of historical persons.

One noted Post-Classic Toltec ruler was named Quetzalcoatl; he may be the same individual as the Kukulcan who invaded Yucatán at about the same time. The Mixtec also recorded a ruler named for the Feathered Serpent. In the 10th century a ruler closely associated with Quetzalcoatl ruled the Toltecs; his name was Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl. This ruler was said to be the son of either the great Chichimeca warrior, Mixcoatl and the Culhuacano woman Chimalman, or of their descent.

The Toltecs had a dualistic belief system. Quetzalcoatl's opposite was Tezcatlipoca, who supposedly sent Quetzalcoatl into exile. Alternatively, he left willingly on a raft of snakes, promising to return.

The Aztec turned him into a symbol of dying and resurrection and a patron of priests. When the Aztecs adopted the culture of the Toltecs, they made twin gods of Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl, opposite and equal; Quetzalcoatl was also called White Tezcatlipoca, to contrast him to the black Tezcatlipoca. Together, they created the world; Tezcatlipoca lost his foot in that process. Because white was the colour symbol of Quezalcoatl, it does not mean Quezalcoatl was white.

Along with other gods, like Tezcatlipoca, and Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl would be called "Ipalnemohuani", which means "by whom we live", a title reserved for the gods directly involved in the creation. Because the name, Ipalnemohuani is singular, this had lead to speculations that the Aztec were becoming monotheist, and all the main gods, were only one. While this interpretation cannot be ruled out, it is probably an oversimpification of the Aztec religion.

In modern times

In some rural parts of Mexico, there still exists a belief that in some caves, near certain towns, there lives a monster, a great feathered snake that can only be seen by special people. The monster must be placated for there to be plentiful rain. The feathered snake is also still worshipped by Huichol and Cora Indians.

The cult of Quetzalcoatl has been more or less idealized, and the image of a "white god" has become part of the popular culture.

Some modern esoteric groups, sometimes called "Mexicanistas", have mixed the cult of Queztalcoatl with modern esoteric practices. There are also claims that Quetzalcoatl was either a lone viking, Levite, Jesus, a survivor from Atlantis, or even an extraterrestrial.

Attributes

The exact significance and attributes of Quetzalcoatl varied somewhat between civilizations and through history. Quetzalcoatl was often considered the god of the morning star, and his twin brother Xolotl was the evening star ( Venus). As the morning star he was known by the title Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, meaning "lord of the star of the dawn." He was known as the inventor of books and the calendar, the giver of maize corn to mankind, and sometimes as a symbol of death and resurrection. Quetzalcoatl was also the patron of the priests and the title of the Aztec high priest.

Most Mesoamerican beliefs included cycles of worlds. Usually, our current time was considered the fifth world, the previous four having been destroyed by flood, fire and the like. Quetzalcoatl allegedly went to Mictlan, the underworld, and created fifth-world mankind from the bones of the previous races (with the help of Cihuacoatl), using his own blood, from a wound, to imbue the bones with new life.

His birth, along with his twin Xolotl, was unusual; it was a virgin birth, to the goddess Coatlicue. Alternatively, he was a son of Xochiquetzal and Mixcoatl.

One Aztec story claims that Quetzalcoatl was seduced by Tezcatlipoca into becoming drunk and sleeping with a celibate priestess, and then burned himself to death out of remorse. His heart became the morning star (see Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli).

Moctezuma Controversy

It has been widely believed that the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II initially believed the landing of Hernán Cortés in 1519 to be Quetzalcoatl's return. This has been questioned by many ethnohistorians (e.g. Matthew Restall 2001) who argue that the Quetzalcoatl-Cortés connection is asserted in no documents created independently of post-Conquest Spanish influence, and that there is little proof of a pre-Hispanic belief in Quetzalcoatl's return. Most documents expounding this theory are of entirely Spanish origin, such as Cortés's letters to Charles V of Spain, in which Cortés goes to great pains to present the naïve gullibility of the Mexicans in general as a great aid in his conquest of Mexico.

Much of the idea of Cortés being seen as a deity can be traced back to the Florentine Codex written down some 50 years after the conquest. In the codex's description of the first meeting between Moctezuma and Cortés, the Aztec ruler is described as giving a prepared speech in classical oratorial Nahuatl, a speech which as described verbatim in the codex (written by Sahagún's, Tlatelolcan informants who were probably not eyewitnesses of the meeting) included such prostrate declarations of divine or near-divine admiration as, "You have graciously come on earth, you have graciously approached your water, your high place of Mexico, you have come down to your mat, your throne, which I have briefly kept for you, I who used to keep it for you," and, "You have graciously arrived, you have known pain, you have known weariness, now come on earth, take your rest, enter into your palace, rest your limbs; may our lords come on earth." Subtleties in, and an imperfect scholarly understanding of, high Nahuatl rhetorical style make the exact intent of these comments tricky to ascertain, but Restall argues that Moctezuma politely offering his throne to Cortés (if indeed he did ever give the speech as reported) may well have been meant as the exactly opposite of what it was taken to mean: politeness in Aztec culture was a way to assert dominance and show superiority. This speech, which has been widely referred to, has been a factor in the widespread belief that Moctezuma was addressing Cortés as the returning god Quetzalcoatl.

Other parties have also propagated the idea that the Native Americans believed the conquistadors to be gods: most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Geronimo Mendieta (Martínez 1980). Some Franciscans at this time held millennarian beliefs (Phelan 1956) and the natives taking the Spanish conquerors for gods was an idea that went well with this theology. Bernardino de Sahagún, who compiled the Florentine Codex, was also a Franciscan.

Some scholars still hold the view that the fall of the Aztec empire can in part be attributed to Moctezumas belief in Cortés as the returning Quetzalcoatl, but most modern scholars see the "Quetzalcoatl/Cortés myth" as one of many myths about the Spanish conquest which have risen in the early post-conquest period.