Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Military History and War; World War II

Mauthausen (known from the summer of 1940 as Mauthausen-Gusen) grew to become a large group of Nazi concentration camps that were built around the villages of Mauthausen and Gusen in Upper Austria, roughly 20 kilometres east of the city of Linz.

Though initially it consisted of a single camp at Mauthausen, with time it was expanded to become one of the largest labour camp complexes in German-controlled Europe. Apart from the four main sub-camps at Mauthausen and nearby Gusen, more than 50 sub-camps, located throughout Austria and southern Germany, used the inmates as slave labour. Several subordinate camps of the KZ Mauthausen complex included quarries, munitions factories, mines, arms factories and Me 262 fighter-plane assembly plants.

In January 1945, the camps, directed from the central office in Mauthausen, contained roughly 85,000 inmates. The death toll remains unknown, although most sources place it between 122,766 and 320,000 for the entire complex. The camps formed one of the first massive concentration camp complexes in Nazi Germany, and were the last ones to be occupied by the Western Allies or the Soviet Union. The two main camps, Mauthausen and Gusen I, were also the only two camps in the whole of Europe to be labelled as "Grade III" camps, which meant that they were intended to be the toughest camps for the "Incorrigible Political Enemies of the Reich". Unlike many other concentration camps, intended for all categories of prisoners, Mauthausen was mostly used for extermination through labour of the intelligentsia, who were educated people and members of the higher social classes in countries subjugated by Germany during World War II.

History

KZ Mauthausen

On August 8, 1938, prisoners from Dachau concentration camp were sent to the town of Mauthausen near Linz, Austria, to begin the construction of a new camp. The location was chosen due to its proximity to the transport hub of Linz, but also because the area was sparsely populated. Although the camp was, from the beginning of its existence, controlled by the German state, it was founded by a private company as an economic enterprise. The owner of the Wiener-Graben quarry (the Marbacher-Bruch, and Bettelberg quarries), which was located in and around Mauthausen, was a DEST Company: an acronym for Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH. The company, led by Oswald Pohl, who was also a high-ranking official of the SS, bought the quarries from the city of Vienna and started the construction of the Mauthausen camp. A year later, the company ordered the construction of the first camp at Gusen. The granite mined in the quarries had previously been used to pave the streets of Vienna, but the Nazi authorities envisioned a complete reconstruction of major German towns in accordance with the plans of Albert Speer and other architects of Nazi architecture, for which large quantities of granite were needed.

The money needed for the construction of the Mauthausen camp was gathered from a variety of sources, including commercial loans from Dresdner Bank and Prague-based Escompte Bank, the so-called Reinhardt's fund (meaning money stolen from the inmates of the concentration camps themselves); and from the German Red Cross.

Mauthausen initially served as a strictly-run prison camp for common criminals, prostitutes and other categories of "Incorrigible Law Offenders". On May 8, 1939 it was converted to a labour camp which was mainly used for the incarceration of political prisoners.

KL Gusen

In late 1939, the Mauthausen camp, with its Wiener-Graben granite quarry, was already overcrowded with prisoners. Their numbers rose from 1,080 in late 1938 to over 3,000 a year later. About that time the construction of a new camp began in Gusen, about 4.5 kilometres away. The new camp (later named Gusen I) and its Kastenhofen quarry were completed in May of 1940. The first inmates were put in the first two huts (No. 7 and 8) on April 17, 1940, while the first transport of prisoners - mostly from the camps in Dachau and Sachsenhausen - arrived on May 25 of the same year.

Like nearby Mauthausen, the Gusen camp also used its inmates as slave labour in the granite quarries, but they also rented them out to various local businesses. In October of 1941, several huts were separated from the Gusen sub-camp by barbed wire and turned into a separate Prisoner of War Labour Camp (German: Kriegsgefangenenarbeitslager). This camp had a large number of prisoners of war incarcerated, mostly Soviet officers. By 1942, the production capacity of both Mauthausen and Gusen had reached its peak. Gusen was expanded to include the central depot of the SS, where various goods, which had been stolen from occupied territories, were sorted and then dispatched to Germany. Local quarries and businesses were in constant need of a new source of labour as more and more Germans were drafted into the Wehrmacht.

In March of 1944, the former SS depot was converted to a new sub-camp, and was named Gusen II. Until the end of the war the depot served as an improvised concentration camp. The camp contained about 12,000 to 17,000 inmates, who were deprived of even the most basic facilities. In December of 1944, another part of Gusen was opened in nearby Lungitz. Here, parts of a factory infrastructure were converted into the third sub-camp of Gusen — Gusen III. The rise in the number of sub-camps could not catch up with the rising number of inmates, which led to overcrowding of the huts in all of the sub-camps of Mauthausen-Gusen. From late 1940 to 1944, the number of inmates per bed rose from 2 to 4.

Mauthausen-Gusen camp system

As the production in all of the sub-camps of Mauthausen-Gusen complex was constantly rising, so was the number of detainees and the number of the sub-camps themselves. Although initially the camps of Gusen and Mauthausen mostly served the local quarries, from 1942, and onwards, they began to be included in the German war machine. To accommodate the ever-increasing number of slave workers, additional sub-camps (German: Außenlager) of Mauthausen began construction in all parts of Austria. At the end of the war the list included 101 camps (including 49 major sub-camps) which covered most of modern Austria, from Mittersill south of Salzburg to Schwechat east of Vienna and from Passau on the pre-war Austro-German border to the Loibl Pass on the border with Yugoslavia. The sub-camps were divided into several categories, depending on their main function: Produktionslager for factory workers, Baulager for construction, Aufräumlager for cleaning the rubble in Allied-bombed towns, and Kleinlager (small camps) where the inmates were working specifically for the SS.

Mauthausen-Gusen as a business enterprise

The production output of Mauthausen-Gusen exceeded that of each of the five other large slave labour centres, including: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Flossenbürg, Gross-Rosen, Marburg and Natzweiler-Struthof, in terms of both production quota and profits. The list of companies using slave labour from the Mauthausen-Gusen camp system was long, and included both national corporations and small, local firms and communities. Some parts of the quarries were converted into a Mauser machine pistol assembly plant. In 1943, an underground factory for the Steyr-Daimler-Puch company was built in Gusen. A similar factory for the Messerschmitt aeroplane-producer was opened near the village of St. Georgen. Altogether, 45 larger companies took part in making KZ Mauthausen-Gusen one of the most profitable concentration camps of Nazi Germany, with more than 11,000,000 Reichsmark of the profits in 1944 alone. Among them were:

| Sub-camp inmate counts Late 1944 – Early 1945 |

|

|---|---|

| Gusen (I, II and III combined) | 26,311 |

| Ebensee | 18,437 |

| Gunskirchen | 15,000 |

| Melk | 10,314 |

| Linz | 6,690 |

| Amstetten | 2,966 |

| Wiener-Neudorf | 2,954 |

| Schwechat | 2,568 |

| Steyr-Münichholz | 1,971 |

| Schlier-Redl-Zipf | 1,488 |

- DEST cartel

- Accumulatoren-Fabrik AFA (the main producer of batteries for German U-Boats)

- Bayer (main German producer of medicines and medications)

- Deutsche Bergwerks- und Hüttenbau

- Linz-based Eisenwerke Oberdonau (a major World War II steel supplier for the German Panzer tanks)

- Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark (aeroplane engine manufacturer)

- Otto Eberhard Patronenfabrik (munitions works)

- Heinkel and Messerschmitt (aeroplane factories, also a V-2 rocket fuselage factory)

- Hofherr und Schrenz

- Österreichische Sauerwerks (arms producer)

- PUCH (vehicles)

- Rax-Werke (machinery and V-2 rockets)

- Steyr (small arms factory)

- Steyr-Daimler-Puch cartel (arms and vehicles)

- Universale Hoch und Tiefbau (construction of tunnels in the Loibl Pass)

Prisoners were also 'rented out' as slave labour, and were exploited in various ways, such as working for local farms, for road construction, reinforcing and repairing the banks of the Danube, and the construction of large residential areas in Sankt Georgen as well as being forced to excavate archaeological sites in Spielberg.

When the Allied strategic bombing campaign started to target the German war industry, German planners decided to move production to underground facilities that were impenetrable to enemy aerial bombardment. In Gusen I, the prisoners were ordered to build several large tunnels beneath the hills surrounding the camp (code-named Kellerbau). By the end of World War II the prisoners had dug 29,400 m² to house a small arms factory. After 1944, similar tunnels were also built beneath the village of Sankt Georgen by the inmates of Gusen II sub-camp (code-named Bergkristall). They dug roughly 50,000 m² so the Messerschmitt company could build an assembly plant to produce the Messerschmitt Me 262 and V-2 rockets. In addition to planes, some 7,000 m² of Gusen II tunnels served as factories for various war materials. In late 1944, roughly 11,000 of the Gusen I and II inmates were working in underground facilities. An additional 6,500 worked on expanding the underground network of tunnels and halls. In 1945, the Me 262 works was already finished and the Germans were able to assemble 1,250 planes a month. This was the second largest plane factory in Germany after the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, which was also underground.

Extermination through labour

The political function of the camp continued in parallel with its economic role. Until at least 1942, it was used for the imprisonment and murder of Germany's political and ideological enemies, both real and imagined. The camp served the needs of the German war machine and also carried out exterminations through labour. When the inmates were totally exhausted, after having worked in the quarries for 12 hours a day; or if they were too ill, or too weak to work, they were then transferred to the Revier ("Krankenrevier", sick barrack) or other places for extermination. Initially, the camp did not have a gas chamber of its own and the so-called Muzulmans, or prisoners who were too sick to work, after being maltreated, under-nourished or totally exhausted, were then transferred to other concentration camps for extermination (mostly to the infamous Hartheim Castle, which was 40.7 km (25.3 miles) away), or killed by lethal injection and cremated in the local crematorium. The growing number of prisoners made the system too expensive and from 1940, Mauthausen was one of the few camps in the West to use a gas chamber on a regular basis. In the beginning, an improvised mobile gas chamber – a van with the exhaust pipe connected to the inside – shuttled between Mauthausen and Gusen. By December of 1941, a permanent gas chamber that could kill about 120 prisoners at a time was completed.

Liberation and post-war heritage

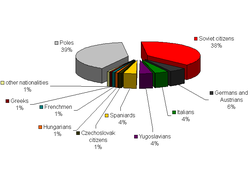

| A chart representing the nationality of the surviving inmates of Gusen I, II and III click the image for more details |

|---|

|

During the final months before liberation, the camp's commander Franz Ziereis prepared for its defence against a possible Soviet offensive. Most of the inmates of German and Austrian nationality "volunteered" for the SS-Freiwillige Häftlingsdivision, an SS unit composed mostly of former concentration camp inmates and headed by Oskar Dirlewanger. The remaining prisoners were rushed to build a line of granite anti-tank obstacles to the east of Mauthausen. The inmates unable to cope with the hard labour and malnutrition were exterminated in large numbers to free space for newly-arrived evacuation transports from other camps, including most of the sub-camps of Mauthausen-Gusen located in eastern Austria. In the final months of the war, the main source of calories, that is the parcels of food sent through the International Red Cross, stopped and food rations became catastrophically low. The prisoners transferred to the "Hospital Sub-camp" received one piece of bread per 20 inmates and roughly half a litre of weed soup a day. This made some of the prisoners, previously engaged in various types of resistance activity, begin to prepare plans to defend the camp in case of an SS attempt to exterminate all the remaining inmates. It is not known why the prisoners of Gusen I and II were not exterminated en-masse, despite direct orders from Heinrich Himmler; Ziereis' plan assumed rushing all the prisoners into the tunnels of the underground factories of Kellerbau and blowing up the entrances. The plan was known to one of the Polish resistance organizations which started an ambitious plan of gathering tools necessary to dig air vents in the entrances.

On April 28, under cover of a fictional air-raid alarm, some 22,000 prisoners of Gusen were rushed into the tunnels. However, after several hours in the tunnels all of the prisoners were allowed to return to the camp. Stanisław Dobosiewicz, the author of a monumental monograph of the Mauthausen-Gusen complex explains that one of the possible causes of the failure of the German plan was that the Polish prisoners managed to cut the fuse wires. Ziereis himself stated in his testimony written on May 25 that it was his wife who convinced him not to follow the order from above. Although the plan was abandoned, the prisoners feared that the SS might want to massacre the prisoners by other means. Because of that the Polish, Soviet and French prisoners prepared a plan for an assault on the barracks of the SS guards in order to seize the arms necessary to put up a fight. A similar plan was also devised by the Spanish inmates.

On May 3, the SS and other guards started to prepare for evacuation of the camp. The following day, the guards of Mauthausen were replaced with unarmed Volkssturm soldiers and an improvised unit formed of elderly police officers and fire fighters evacuated from Vienna. The police officer in charge of the unit accepted the "inmate self-government" as the camp's highest authority and Martin Gerken, until then the highest-ranking kapo prisoner in the Gusen's administration (in the rank of Lagerälteste, or the Camp's Elder), became the new de facto commander. He attempted to create an International Prisoner Committee that would become a provisional governing body of the camp until it was liberated by one of the approaching armies, but he was openly accused of co-operation with the SS and the plan failed. All work in the sub-camps of Mauthausen stopped and the inmates focused on preparations for their liberation - or defence of the camps against a possible assault by the SS divisions concentrated in the area. The remnants of several German divisions indeed assaulted the Mauthausen sub-camp, but were repelled by the prisoners who took over the camp. Out of all the main sub-camps of Mauthausen-Gusen only Gusen III was to be evacuated. On May 1 the inmates were rushed on a death march towards Sankt Georgen, but were ordered to return to the camp after several hours. The operation was repeated the following day, but called off soon afterwards. The following day, the SS guards deserted the camp, leaving the prisoners to their own fate.

The camps of Mauthausen-Gusen were the last to be liberated during the World War II. On May 5, 1945, the camp at Mauthausen was approached by soldiers of the 41st Recon Squad of the US 11th Armoured Division, 3rd US Army. The reconnaissance squad was led by S/SGT Albert J. Kosiek. His troop disarmed the policemen and left the camp. By the time of its liberation, most of the SS-men of Mauthausen had already fled; however, some 30 who were left were lynched by the prisoners; a similar number were lynched in Gusen II. Until May 6 all the remaining sub-camps of the Mauthausen-Gusen camp complex, with the exception of the two camps in the Loibl Pass, were also liberated by American forces.

Among the inmates liberated from the camp was Lieutenant Jack Taylor, an officer of the Office of Strategic Services. He had managed to survive with the help of several prisoners and was later a key witness at the Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials carried out by the Dachau International Military Tribunal. Another of the camp's survivors was Simon Wiesenthal, an engineer who spent the rest of his life hunting Nazi war criminals.

Following the capitulation of Germany, the Mauthausen-Gusen complex fell within the Soviet sector of occupation of Austria. Initially, the Soviet authorities used parts of the Mauthausen and Gusen I camps as barracks for the Red Army. At the same time, the underground factories were being dismantled and sent to the USSR as a war booty. After that, between 1946 and 1947, the camps were unguarded and many furnishings and facilities of the camp were dismantled, both by the Red Army and by the local population. In the early summer of 1947, the Soviet forces had blown the tunnels up and were then withdrawn from the area, while the camp was turned over to Austrian civilian authorities. However, it was not until 1949 that it was declared a national memorial site. Finally, 30 years after camp's liberation, on May 3, 1975, Chancellor Bruno Kreisky officially opened the Mauthausen Museum. Unlike Mauthausen, much of what constituted the sub-camps of Gusen I, II and III is now covered by residential areas built there after the war.