History of Poland (1945–1989)

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Recent History

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 spans the period of Soviet Communist dominance over the People's Republic of Poland following World War II. These years, while featuring many improvements in the standards of living in Poland, were marred by social unrest and economic depression.

Near the end of World War II, German forces were driven from Poland by the advancing Soviet Red Army, and the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a provisional pro-Communist Polish coalition government; many Poles see this as a betrayal of their country by the Allied Powers in order to appease the Soviet leader Josef Stalin. The new government in Warsaw increased its political power and over the next two years the Communist Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) under Bolesław Bierut gained control of the People's Republic of Poland, which would become part of the postwar Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. A liberalizing "thaw" in Eastern Europe following Stalin's death in early 1953 caused a more liberal faction of the Polish Communists of Władysław Gomułka to gain power. Poland enjoyed a period of relative stability over the next decade, but by the mid-1960s, Poland was experiencing increasing economic, as well as political, difficulties. In December 1970, the government suddenly announced massive increases in the prices of basic foodstuffs in an attempt to prevent economic collapse. A wave of strikes followed as the outraged populace demonstrated against the heavy increases, and government introduced a new economic program based on large-scale borrowing from the West. The program resulted in an immediate rise in living standards and expectations, but it faltered because of the 1973 oil crisis. In the late 1970s the government of Edward Gierek was finally forced to raise prices, and this led to another wave of public protests.

This vicious cycle was finally interrupted by the 1978 election of Karol Wojtyla as Pope John Paul II. This unexpected event had an electrifying effect on the opposition to Communism in Poland. In early August 1980, the wave of strikes led among others by an electrician named Lech Wałęsa, founder of the independent trade union " Solidarity" ( Polish Solidarność) forced government of Wojciech Jaruzelski to declare martial law in December 1981 and imprison most of the opposition leaders. However, change was inevitable. Eventually, with the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union, increasing pressure from the Roman Catholic Church and trade unions, and massive foreign debts, the Communists were forced to negotiate with their opponents. In 1988, the Round Table Talks radically altered the structure of Polish government and society. In April 1989, Solidarity was again legalized and allowed to participate in the upcoming elections; its candidates' striking victory in those limited elections sparked off a succession of peaceful transitions from Communist rule in Central and Eastern Europe. In 1990, Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's leader. He was succeeded by Wałęsa in December. By the end of August, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed, and in December, Wałęsa was elected president and the Communist People's Republic of Poland again became the Republic of Poland.

Creation of the People's Republic of Poland (1945–1956)

Wartime devastation

Poland suffered enormous losses during World War II. While in 1939 Poland had 35.1 million inhabitants, the census of February 14, 1946 showed only 23.9 million. Over ninety percent of Poland's capital was destroyed in the aftermath of the Warsaw Uprising. Poland, still a predominantly agricultural country compared to Western nations, suffered catastrophic damage to its infrastructure during the war, and lagged even further behind the West in industrial output in the War's aftermath.

The implementation of the immense task of reconstructing the country was accompanied by the struggle of the new government to acquire a stable, centralized power base, further complicated by the mistrust a considerable part of the society held for the new regime and by disputes over Poland's postwar borders, which were not firmly established until mid-1945. In 1947 Soviet influence caused the Polish government to reject the most successful post-war reconstruction motion, the Marshall Plan, and in 1949 to join the Soviet Union-dominated Comecon. At the same time Soviet forces have engaged in plunder on territories of Poland, striping it of valuable industrial equipment, infrastructure and factories and sending them to Soviet Union .

Consolidation of Communist power (1945—1948)

Even before the Red Army entered Poland, the Soviet Union was pursuing a deliberate strategy to eliminate anti-Communist resistance forces in order to ensure that Poland would fall under its sphere of influence. Stalin had severed relations with the Polish government-in-exile in London in 1943, but to appease the United States and the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union agreed at the Yalta Conference in 1944 to form a coalition government composed of the Communist Polish Workers' Party, members of the pro-Western Polish government in exile, and members of the Armia Krajowa ("Home Army") resistance movement, as well as to allow for free elections to be held.

From its outset, the Yalta decision favored the Communists, who enjoyed the advantages of Soviet support, high morale, control over crucial ministries such as the security services, and Moscow's determination to bring Eastern Europe securely under its influence. With the beginning of the liberation of Polish territories and the failure of the Armia Krajowa's Operation Tempest in 1944, control over Polish territories passed from the occupying forces of Nazi Germany to the Red Army, and from the Red Army to the Polish Communists, who held the largest influence under the provisional government.

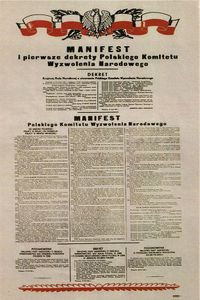

The Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, resigned his post in 1944 and, along with several other Polish exiled leaders, returned to Poland, where a Provisional Government (Rząd Tymczasowy Republiki Polskiej; RTTP), had been created by the Communist-dominated Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego; PKWN) in Lublin. This government was headed by Socialist Edward Osóbka-Morawski, but the Communists held a majority of key posts. Both of these governments were subordinate to the unelected, Communist-controlled parliament, the State National Council (Krajowa Rada Narodowa; KRN) and were not recognized by the Polish government-in-exile, which had formed its own quasi-parliament, the Council of National Unity (Rada Jedności Narodowej; RJN).

In April 1945, the Provisional Government formed an alliance with the Soviet Union. The new Polish Provisional Government of National Unity (Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej; TRJN) — as the Polish government was called until the elections of 1947 — was finally established on June 28, with Mikołajczyk as Deputy Prime Minister. The Communist Party's principal rivals were the veterans of the Armia Krajowa movement, along with Mikołajczyk's Polish Peasant Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe; PSL), and the veterans of the Polish armies which had fought in the west. But at the same time, Soviet-oriented parties, backed by the Soviet Red Army and in control of the security forces, held most of the power, especially in the Polish Workers' Party (Polska Partia Robotnicza; PPR) under Władysław Gomułka and Bolesław Bierut.

Mikołajczyk and his colleagues in the Polish government-in-exile insisted on making a stand in the defense of Poland's pre-1939 eastern border (the Curzon Line and Kresy region) as a basis for the future Polish-Soviet border. However, this was a position which could not be defended in practice — Stalin was in occupation of the territory in question, and he had already been promised those areas by Churchill and Roosevelt in 1943. The government-in-exile's refusal to accept the proposed new Polish borders infuriated the Allies, particularly Churchill, making them less inclined to oppose Stalin on issues of how Poland's postwar government would be structured. In the end, the exiles lost on both issues: Stalin annexed the eastern territories, and took control of the new Polish government. However, Poland preserved its status as an independent state, despite the arguments of some influential Communists, such as Wanda Wasilewska, in favour of Poland becoming a republic of the Soviet Union.

Stalin had promised at the Yalta Conference that free elections would be held in Poland. However, the Polish Communists, led by Gomułka and Bierut, were conscient of lack of support of their side in the Polish society. Because of that, in 1946 a national referendum, known as " 3 times YES" (3 razy TAK; 3xTAK), was held instead of the parliamentary elections. The referendum comprised three, fairly general questions, and was meant to check the popularity of the communist rule in Poland. Because all of the important parties in Poland at that time were mostly leftists and could have supported all off the options, the Mikołajczyk's PSL decided to ask its supporters to oppose the abolition of the senate, while the Communist democratic bloc supported the "3 times Yes" option. The referendum showed that the communist plans met with little support, with less than a third of the Polish population. Only vote rigging won them a majority in the carefully controlled poll. Following the forged referendum, the Polish economy started to become nationalized.

The Communists consolidated power by gradually whittling away the rights of their non-Communist foes, particularly by suppressing the leading opposition party, Mikołajczyk's Polish Peasant Party. In some cases, their opponents were sentenced to death — among them Witold Pilecki, the organizer of the Auschwitz resistance, and many leaders of Armia Krajowa and the Council of National Unity (in the Trial of the Sixteen). The opposition was also persecuted by administrative means, with many of its members murdered or forced to exile. Although the initial persecution of these former anti-Nazi organizations forced many thousands of partisans back into forests, the actions of the Służba Bezpieczeństwa, NKVD and Red Army steadily diminished their number. In 1947, an amnesty was passed for most of the partisans; the Communist authorities expected around 12,000 people to give up their arms, but the actual number of people to come out of the forests eventually reached 53,000.

By 1946, rightist parties had been outlawed. A pro-government " Democratic Bloc" formed in 1947 that included the forerunner of the communist Polish United Workers' Party and its leftist allies. By January 1947, the first parliamentary election allowed only opposition candidates of the Polish Peasant Party, which was nearly powerless due to government controls. Results were adjusted by Stalin himself to suit the Communists, and under these conditions, the regime's candidates gained 417 of 434 seats in parliament ( Sejm), effectively ending the role of genuine opposition parties. Many members of opposition parties, including Mikołajczyk, left the country. Western governments did not protest, which led many anti-Communist Poles to speak of postwar " Western betrayal". In the same year, the new Legislative Sejm created the Small Constitution of 1947, and over the next two years, the Communists would ensure their rise to power by monopolizing political power in Poland under the PZPR. The Communists admitted in the last year of their rule that they had resorted to systematic vote rigging, both in a referendum in June 1946 that legitimized the provisional government, and in the 1947 parliamentary elections, which returned a massive majority for the Communist-controlled "Democratic Bloc".

Another force in Polish politics, Józef Piłsudski's old party, the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna; PPS), suffered a fatal split at this time, as the communist applied the salami tactics to dismember any opposition. One faction, which included Osóbka-Morawski, wanted to join forces with the Peasant Party and form a united front against the Communists. Another faction, led by Józef Cyrankiewicz, argued that the Socialists should support the Communists in carrying through a socialist program, while opposing the imposition of one-party rule. Pre-war political hostilities continued to influence events, and Mikołajczyk would not agree to form a united front with the Socialists. The Communists played on these divisions by dismissing Osóbka-Morawski and making Cyrankiewicz Prime Minister. In 1948, the Communists and Cyrankiewicz's faction of Socialists merged to form the Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; PZPR). Mikołajczyk was forced to leave the country, and Poland became a de facto single-party state and a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Two small façade parties, one for farmers ( Zjednoczone Stronnictwo Ludowe) and one for the intelligentsia ( Stronnictwo Demokratyczne), were allowed to exist, both subordinate to the Communists. A period of Sovietization and Stalinism started.

The Bierut era (1948–1956)

The new Polish government was controlled by Polish Communists who had spent the war in the Soviet Union. They were "assisted" — and in some cases controlled — by Soviet "advisers" who were placed in every part of the government. The most important of these advisers was Konstantin Rokossovsky (Konstanty Rokossowski in Polish), the Defense Minister from 1949 to 1956. Although of Polish parentage, he had spent his adult life in the Soviet Union, and had attained the rank of Marshal in the Soviet Armed Forces.

This government, headed by Cyrankiewicz and economist Hilary Minc, carried through a program of sweeping economic reform and national reconstruction. In what became known as the battle for the trade, the private industry was nationalized, the land seized from prewar landowners was redistributed to the peasants, and millions of Poles transferred from the eastern territories annexed by the Soviet Union into the western territories, which Soviets transferred from Germany to Poland. By 1950, 5 million Poles had been settled in what the government called the Regained Territories. Warsaw and other ruined cities were cleared of rubble — mainly by hand — and rebuilt with remarkable speed.

The reforms were greeted with relief by much of the population, though latent popular discontent remained present, with opinion varying. Some Poles adopted an attitude that might be called "resigned cooperation". Others, including the tens of thousands of Poles who had joined the Communist Party and some Social Democratic, Communist and Trade Unionist Poles, celebrated the opportunity to create what they saw as the society of the future. Others, particularly the remnants of the Armia Krajowa, led by Narodowe Siły Zbrojne and Wolność i Niezawisłość, known as the cursed soldiers, actively opposed the Communists, expecting a World War III that would liberate Poland. Although most had surrendered during the amnesty of 1947, the brutal repressions by the secret police led many of them back into the forests, where a few continued to fight well into the 1950s.

The Polish Communists themselves were divided into two informal factions, named Natolin and Puławy after the locations where they held their meetings: the Palace of Natolin near Warsaw and Puławska Street in Warsaw. Natolin consisted largely of ethnic Poles of peasant origin who in large part had spent the war in occupied Poland, and had a peculiar nationalistic-communistic ideology. Headed by Władysław Gomułka, the faction underlined the national character of Polish local communist movement. Puławy faction included Jewish Communists, as well as members of the old Communist intelligentsia, who in large part spent the war in the USSR and supported the Sovietization of Poland. The repercussions of Yugoslavia's break with Stalin reached Warsaw in 1948. As in the other eastern European satellite states, there was a purge of Communists suspected of nationalist or other "deviationist" tendencies in Poland. In September, Gomułka, who had always been an opponent of Stalin's control of the Polish party, was accused of "nationalistic tendency", dismissed from his posts, and imprisoned. However no equivalent of the show trials that took place in the other Eastern European states occurred, and Gomułka escaped with his life. Bierut replaced him as party leader.

The Stalinist turn that led to the ascension of Bierut meant that Poland would now be brought into line with the Soviet model of a " people's democracy" and a centrally planned socialist economy, in place of the façade of democracy and market economy which the regime had preserved until 1948. The regime also embarked on the collectivization of agriculture, although the pace for this change was slower than in other satellites; Poland remained the only Soviet bloc country where individual peasants dominated agriculture. The Communists further alienated many Poles by persecuting the Catholic Church. The Stowarzyszenie PAX ("PAX Association") created in 1947 worked to undermine grassroot support from the Church and attempted to create a Communist Catholic Church. In 1953 the Primate of Poland, Stefan Cardinal Wyszyński, was placed under house arrest, although before that he had been willing to make many compromises with the government.

Despite the fact that Polish historians estimate that between 200,000 and 400,000 people died during the postwar period, Stalinism in Poland was not quite as severe as it was in the other satellite states. Many Poles believed that the reason for this was that Poland, unlike other Eastern European countries, did not need an additional phase of terror. Polish society had already been brought to the edge of disintegration by the Nazi occupation: Warsaw and other cities lay in ruins, and many smaller towns, which had been populated largely by Jews before the War, were empty. Half of the prewar Polish intelligentsia, mainly those of Jewish or middle-class origins, was dead or in political exile. Many children had gone six years without school. Under these circumstances, most people were willing to accept even Communist rule in exchange for the restoration of relatively normal life. Even the Catholic Church believed that any open resistance would be suicidal. In such circumstances a struggle for total control of every aspect of social and economical life in Poland started.

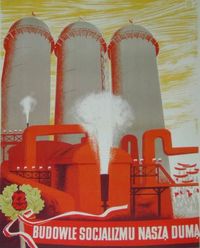

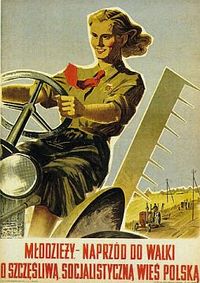

In the early 1950's the Communist regime carried out major changes to the education system. The Nazi massacre of the prewar Polish intelligentsia, and the emigration of many other intellectuals and skilled people, had left Poland severely educationally lacking. As a result, the Communist program of free and compulsory school education for all, and the establishment of new free universities, received much support. Universities from the lost eastern territories were evacuated to the new western territories: from Wilno to Toruń and from Lwów to Wrocław. Many new universities were founded, including the famous Film University of Łódź. The Communists thus took the opportunity to create a new Polish educated class, taught in an educational system which they controlled. At the same time between 1951 and 1953 a large number of pre-war reactionary professors was dismissed from the universities. Among them were Maria and Stanisław Ossowski, Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Izydora Dąmbska and many of the most prominent Polish scientists of the epoch. At the same time the control over art and artists was extended and with time the Socialist Realism became the only movement that was accepted by the authorities. After 1949 most of works of art presented to the public had to be in line with the voice of the Party and present its propaganda.

In 1948 the United States announced the Marshall plan, its initiative to help rebuild Europe. After initially welcoming the idea of Polish involvement in the plan, the Polish government declined to participate under pressure from Moscow. In 1953, following anti-Communist riots in the German Democratic Republic, Poland was forced by the Soviet Union to give up its claims to compensation from Germany, which as a result paid no significant compensation for war damages, either to the Polish state or to Polish citizens. The only compensation Poland received was in the form of the property left behind by the German population of the annexed western territories. This marked the beginning of the wealth gap, which would increase in years to come, as the Western market economies grew much more quickly than the centrally planned socialist economies of Eastern Europe.

The new Polish Constitution of 1952 officially established Poland as a People's Republic, ruled by the Polish United Workers' Party, which since the absorption of the left wing of the Socialist Party in 1948 had been the Communist Party's official name. The post of President of Poland was abolished, and Bierut, the First Secretary of the Communist Party, became the effective leader of Poland.

Minorities in Poland after the Second World War

Before World War II, a third of Poland's population was composed of ethnic minorities. After the war, however, Poland's minorities were all but gone, due to the 1945 revision of borders, and the Holocaust that resulted in the extermination of the vast majority of Poland's Jews. Under the National Repatriation Office (Państwowy Urząd Repatriacyjny), millions of Poles were forced to leave their homes in the eastern Kresy region and settle in the western former German territories. At the same time, according to the provisions of the Potsdam Agreement, approximately 5 million remaining Germans (about 8 million had already fled or had been expelled and about 1 million had been killed in 1944-46) were similarly expelled from those territories into the post-war borders of Germany. Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities found themselves now mostly within the borders of the Soviet Union; those who opposed this new policy (like the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in the Bieszczady Mountains region) were suppressed by the end of 1947 in the "Wisła" Action.

The population of Jews in Poland, which formed the largest Jewish community in pre-war Europe at about 3.5 million people, was all but destroyed by 1945. Approximately 3 million Jews (all but about 300,000 to 500,000 of the Jewish population) died of starvation in ghettos and labor camps, were slaughtered at the Nazi extermination camps or by the Einsatzgruppen death squads. Between 40,000 and 100,000 Polish Jews survived the Holocaust in Poland, and another 50,000 to 170,000 were repatriated from the Soviet Union, and 20,000 to 40,000 from Germany and other countries. At its postwar peak, there were 180,000 to 240,000 Jews in Poland, settled mostly in Warsaw, Łódź, Kraków and Wrocław.

The position of Jews in postwar Poland was precarious. Many of the Holocaust survivors shared the common fate of other people in post-war Communist Poland, and were not able to reclaim their property upon return. There were incidents of Jews who were returning to their old homes being attacked by people who had moved into their homes during the war. Jews were also sometimes associated with the Communists, as some Jews who returned from the Soviet Union, including Hilary Minc and Party security and ideological chief Jakub Berman, assumed prominent positions in Communist leadership and were as a result held responsible for the regime's repressions by many Poles. These issues fed into existing anti-Semitism, culminating in the Kielce pogrom of July 1946. Sparked by falsified rumors of Jewish blood libel, a crowd attacked a building housing Jews preparing to emigrate to Palestine while the police stood by and watched—even assisting in some cases—killing over 40 and wounding approximately 50. Afterwards, the Communists, anti-Communists and Catholic Church all blamed each other for this outbreak of violence. Kielce became a turning point for the Jews in post-war Poland. Until the pogrom, large numbers of Polish Jews had intended to stay in the country, despite the general Zionist feeling after the war. After the pogrom, the majority of Jews wanted to leave—the number of Jews crossing the border illegally skyrocketed, going from an average of 1,000 a month prior to July 1946 to over 20,000 a month for the three months afterwards. In total, 100,000 to 120,000 Jews left Poland between 1945 and 1948. Their departure was largely organized by the Zionist activists in Poland, such as Adolf Berman and Yitzhak Zuckerman, under the umbrella of a semi-clandestine organization, Berihah ("Flight"). A second wave of Jewish emigration (50,000) took place during the liberalization of the Communist regime between 1957 and 1959.

Communist reform (1956–1970)

De-Stalinization

Stalin had died in 1953. Between 1953 and 1958 Nikita Khrushchev outmaneuvered his rivals and achieved power in the Soviet Union. In March 1956 Khrushchev denounced Stalin's cult of personality at the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party. The de-Stalinization of official Soviet ideology left Poland's Stalinist hard-liners in a difficult position. In the same month as Khrushchev's speech, as unrest and desire for reform and change among both intellectuals and workers was beginning to surface throughout the Eastern Bloc, the death of the hard-line Bierut in March 1956 exacerbated an existing split in the PZPR. Bierut was succeeded by Edward Ochab as First Secretary of the PZPR, and by Cyrankiewicz as Prime Minister.

In June 1956, workers in the industrial city of Poznań went on strike. Demonstrations by striking workers turned into huge riots, in which 80 people were killed. Cyrankiewicz tried to repress the riots at first, threatening that "any provocateur or lunatic who raises his hand against the people's government may be sure that this hand will be chopped off." But soon the hard-liners realized that they had lost the support of the Soviet Union, and the regime turned to conciliation: it announced wage rises and other reforms. Voices began to be raised in the Party and among the intellectuals calling for wider reforms of the Stalinist system. The disgraced "national Communist" Władysław Gomułka re-emerged and placed himself at the head of the movement.

Realizing the need for new leadership, the PZPR chose Gomułka, a moderate who had been purged after losing his battle with Bierut, as First Secretary in October 1956, despite Moscow's threats to take action against Poland if the PZPR picked Gomułka; the Soviet Union did not intend to allow its influence on Eastern Europe to diminish. After some tough bargaining with Khrushchev, who came to Warsaw to oversee the transfer of power, the Soviets grudgingly decided not to resist Gomułka's rise to power. Even so, Poland's relations with the Soviet Union were not nearly as strained as Yugoslavia's. As a further sign that the end of Soviet influence in Poland was nowhere in sight, the Warsaw Pact was signed in the Polish capital of Warsaw on May 14, 1955, to counteract the establishment of the Western NATO.

Hard-line Stalinists such as Berman were removed from power, and many Soviet officers serving in the Polish Armed Forces were dismissed, but almost no one was put on trial for the repressions of the Bierut period. The Puławy faction argued that mass trials of Stalin-era officials, many of them Jewish, would incite animosity toward the Jews. Konstantin Rokossovsky and other Soviet advisors were sent home, and Polish Communism took on a more independent orientation. However, Gomułka knew that the Soviets would never allow Poland to leave the Warsaw Pact because of Poland's strategic position between the Soviet Union and Germany. He agreed that Soviet troops could remain in Poland, and that no overt anti-Soviet outbursts would be allowed. In this way, Poland avoided the risk of the kind of Soviet armed intervention that crushed the revolution in Hungary that same month.

There were also repeated attempts by some Polish academics and philosophers, such as Leszek Kołakowski, Tadeusz Kotarbiński, Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz and Stanisław Ossowski, to develop a specific form of Polish Marxism. While their attempts to create a bridge between Poland's history and Soviet Marxist ideology were mildly successful, especially in comparison to similar efforts in most other countries of the Eastern Bloc, they were for the most part stifled due to the regime's unwillingness to risk the wrath of the Soviet Union for going too far from the Soviet party line.

The Gomułka period

Poland welcomed Gomułka's return to power with relief, and even euphoria, despite his background as a lifelong Communist. Many Poles still rejected Communism, but they knew that the realities of Soviet dominance dictated that Poland could not escape from Communist rule. Gomułka, however, promised an end to police terror, greater intellectual and religious freedom, higher wages and the reversal of collectivization, and he fulfilled all of these promises. Gomułka also promised free elections, but this was a promise he knew he could not keep without seeing his party defeated. At the January 1957 elections, no opposition candidates were permitted to run. Voters were given the right to vote against official candidates, but Gomułka persuaded the Catholic Church to urge a vote of confidence in the government. In this way, the PZPR won 237 seats out of 459, while the rest went to satellite parties and a few independents.

After the first wave of reform, Gomułka's regime settled into a phase of "consolidation" in which the power of the Party, and Party's control of the media and universities, were gradually restored, and many of the younger and more reformist members of the Party were expelled. The reform-promising Gomułka of 1956 was replaced by the original authoritarian Gomułka. Poland enjoyed a period of relative stability over the next decade, but the idealism of the " Polish October" had faded away. What replaced it was a cynical form of Polish nationalism, fueled by a propaganda campaign against West Germany over its unwillingness to recognize the Oder-Neisse line.

By the mid-1960s, Poland was starting to experience economic, as well as political, difficulties. Like all the Communist regimes, Poland was spending too much on heavy industry, armaments and prestige projects, and too little on consumer production. The end of collectivization returned the land to the peasants, but most of their farms were too small to be efficient, so productivity in agriculture remained low. Economic relations with West Germany were frozen because of the impasse over the Oder-Neisse line. Gomułka chose to ignore the economic crisis, and his autocratic methods prevented the major changes required to prevent a downward economic spiral.

Gomułka's Poland was generally described as one of the more "liberal" Communist regimes, and Poland was certainly more open than East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Romania during this period. Nevertheless, under Gomułka, Poles could still go to prison for writing political satire about the Party leader, as Janusz Szpotański did, or for publishing a book abroad. Jacek Kuroń, who would later become a prominent dissident, was imprisoned for writing an "open letter" to other Party members. As Gomułka's popularity declined and his reform Communism lost its impetus, the regime became steadily less liberal and more repressive.

By the 1960s, other government officials had begun to plot against Gomułka. His security chief, Mieczysław Moczar, a wartime Communist partisan commander, formed a new faction, "the Partisans", based on principles of Communist nationalism and anti-Jewish sentiment. The Party boss in Upper Silesia, Edward Gierek, who unlike most of the Communist leaders was a genuine product of the working class, also emerged as a possible alternative leader.

In March 1968 student demonstrations at Warsaw University broke out when the government banned the performance of a play by Adam Mickiewicz ( Dziady, written in 1824) at the Polish Theatre in Warsaw, on the grounds that it contained "anti-Soviet references". Moczar used this affair as a pretext to launch an anti-Semitic press campaign (although the expression "anti-Zionist" was the one officially used). By 1968, most of Poland's 40,000 remaining Jews were assimilated into Polish society, but over the next year, they became the centre of an organized campaign to equate Jewish origins with Zionist sympathies and thus disloyalty to Poland. Approximately 20,000 Jews lost their jobs and had to emigrate. The campaign, despite being ostensibly directed at Jews who had held office during the Stalin era and their families, affected most of the remaining Polish Jews, regardless of background. Gomułka had the option of resisting this campaign, but instead allowed it to continue, hoping that it would burn itself out. The campaign damaged Poland's reputation abroad, particularly in the United States. Many Polish intellectuals opposed the campaign, some openly, and Moczar's security apparatus became as hated as Berman's had been.

There were several results of these March 1968 events. One was an official approval for demonstrating Polish national feelings, including the scaling down of official criticism of the prewar Polish regime, and of Poles who had fought in the anti-Communist wartime partisan movement, the Armia Krajowa. The second was the complete alienation of the regime from the leftist intelligentsia, who were disgusted at the official promotion of anti-Semitism. The third was the founding by Polish Emigrants to the West of organizations that encouraged opposition within Poland.

Two things saved Gomułka's regime at this point. First, the Soviet Union, now led by Leonid Brezhnev, made it clear that it would not tolerate political upheaval in Poland at a time when it was trying to deal with the crisis in Czechoslovakia. In particular, the Soviets made it clear that they would not allow Moczar, whom they suspected of anti-Soviet nationalism, to be leader of Poland. Secondly, the workers refused to rise up against the regime, partly because they distrusted the intellectual leadership of the protest movement, and partly because Gomułka placated them with higher wages. The Catholic Church, while protesting against police violence against demonstrating students, was also not willing to support a direct confrontation with the regime.

In August 1968 the Polish army took part in the invasion of Czechoslovakia. Some Polish intellectuals protested, and Ryszard Siwiec burned himself alive during the official national holiday celebrations. Polish participation in crushing Czech liberal communism (or socialism with a human face, as it was called at that time) further alienated Gomułka from his former liberal supporters. However, in 1970 Gomułka won a political victory when he gained West German recognition of the Oder-Neisse line. The German Chancellor, Willy Brandt, asked on his knees for forgiveness for the crimes of the Nazis: the gesture was understood in Poland as being addressed to Poles, although it was actually made at the site of the Warsaw Ghetto and was thus directed primarily toward the Jews. This occurred five years after Polish bishops had issued the famous Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish Bishops to the German Bishops.

Gomułka's temporary political success could not mask the economic crisis into which Poland was drifting. Although the system of fixed, artificially low food prices kept urban discontent under control, it caused stagnation in agriculture and made more expensive food imports necessary. This situation was unsustainable, and in December 1970, the regime suddenly announced massive increases in the prices of basic foodstuffs. It is possible that the price rises were imposed on Gomułka by enemies of his in the Party leadership who planned to maneuver him out of power. The raised prices were unpopular among many urban workers. Gomułka believed that the agreement with West Germany had made him more popular, but in fact most Poles seemed to feel that since the Germans were no longer a threat to Poland, they no longer needed to tolerate the Communist regime as a guarantee of Soviet support for the defense of the Oder-Neisse line.

Demonstrations against the price rises broke out in the northern coastal cities of Gdańsk, Gdynia, Elbląg and Szczecin. Gomułka's right-hand man, Zenon Kliszko, made matters worse by ordering the army to fire on workers as they tried to return to their factories. Another leader, Stanisław Kociołek, appealed to the workers to return to work. However, in Gdynia the soldiers had orders to prevent workers from returning to work, and they fired into a crowd of workers emerging from their trains; hundreds of workers were killed. The protest movement spread to other cities, leading to more strikes and causing angry workers to occupy many factories.

The Party leadership met in Warsaw and decided that a full-scale working-class revolt was inevitable unless drastic steps were taken. With the consent of Brezhnev in Moscow, Gomułka, Kliszko and other leaders were forced to resign; if the price rises had been a plot against Gomułka, it had succeeded. Since Moscow would not accept the appointment of Moczar, Edward Gierek was drafted as the new First Secretary of the PZPR. Prices were lowered, wage increases were announced, and sweeping economic and political changes were promised. Gierek went to Gdańsk and met the workers personally, apologizing for the mistakes of the past, and saying that as a worker himself, he would now govern Poland for the people.

The Gierek era (1970–1980)

Gierek, like Gomułka in 1956, came to power on a raft of promises that now everything would be different: wages would rise, prices would remain stable, there would be freedom of speech, and those responsible for the violence at Gdynia and elsewhere would be punished. Although Poles were much more cynical than they had been in 1956, Gierek was believed to be an honest and well-intentioned man, and his promises bought him some time. He used this time to create a new economic program, one based on large-scale borrowing from the West—mainly from the United States and West Germany—to buy technology that would upgrade Poland's production of export goods. This massive borrowing, estimated to have totaled US$10 billion, was used to re-equip and modernize Polish industry, and to import consumer goods in order to give the workers more incentive to work.

For the next four years, Poland enjoyed rapidly rising living standards and an apparently stable economy. Real wages rose 40% between 1971 and 1975, and for the first time most Poles could afford to buy cars, televisions and other consumer goods. Poles living abroad, veterans of the Armia Krajowa and the Polish II Corps, were invited to return and to invest their money in Poland, which many did. The peasants were subsidized to grow more food. Poles were able to travel—mainly to Germany, Sweden and Italy—with little difficulty. There was also some cultural and political relaxation. As long as the "leading role of the Party" and the Soviet "alliance" were not criticized, there was a limited freedom of speech. With the workers and peasants reasonably happy, the regime knew that a few grumbling intellectuals could pose no challenge.

"Consumer Communism", based on present global economic conditions, raised Polish living standards and expectations, but the program faltered suddenly in the early 1970s because of worldwide recession and increased oil prices. The effects of the world oil shock following the 1973 Arab-Israeli War produced an inflationary surge followed by a recession in the West, which resulted in a sharp increase in the price of imported consumer goods, coupled with a decline in demand for Polish exports, particularly coal. Poland's foreign debt rose from US$100 million in 1971 to US$6 billion in 1975, and continued to rise rapidly. This made it more and more difficult for Poland to continue borrowing from the West. Once again, consumer goods began to disappear from Polish shops. The new factories built by Gierek's regime also proved to be largely ineffective. For instance, one of the major investments was in an Italian-built cake and sweets factory in Ryki. It was the largest such factory in the world, and was to produce 17 million cakes a week. However, it soon turned out that most of the ingredients had to be imported from abroad at high prices, and the factory was closed soon after its completion.

In 1975, Poland and almost all other European countries became signatories of the Helsinki Accords and a member of Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the creation of which marked the high point of the period of " détente" between the Soviet Union and the United States. Despite the regime's claims that the freedoms mentioned in the agreement would be implemented in Poland, there was little change. However, Poles were gradually becoming more aware of the rights they were being denied.

As the government became increasingly unable to borrow money from abroad, it had no alternative but to raise prices, particularly for basic foodstuffs. The government had been so afraid of a repeat of the 1970 worker rebellion that it had kept prices frozen at the 1970 levels rather than allowing them to rise gradually. Then, in June 1976, under pressure from Western creditors, the government again introduced price increases: butter by 33%, meat by 70%, and sugar by 100%. The result was an immediate nationwide wave of strikes, with violent demonstrations and looting at Płock and Radom. Gierek backed down at once, dismissing Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz and repealing the price rises. This left the government looking both economically foolish and politically weak, a very dangerous combination.

The 1976 disturbances and the subsequent arrests and dismissals of worker militants brought the workers and the intellectual opposition to the regime back into contact. A group of intellectuals led by Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik founded the Committee for the Defence of the Workers (Komitet Obrony Robotników; KOR), which published an underground paper, Robotnik ("The Worker"—the same title as Józef Piłsudski's underground paper). The aim of the KOR was at first simply to assist the worker victims of the 1976 repression, but it inevitably became a political resistance group. It marked an important development: the intellectual dissidents accepting the leadership of the working class in opposing the regime. These events brought many more Polish intellectuals into active opposition of the Polish government. The complete failure of the Gierek regime, both economically and politically, led many of them to join or rejoin the opposition. During this period, new opposition groups were formed, such as the Confederation for an Independent Poland and the Movement for Defense of Human and Civic Rights (ROPCiO), which tried to resist the regime by denouncing it for violating Polish laws and the Polish constitution.

For the rest of the 1970s, resistance to the regime grew, in the form of trade unions, student groups, clandestine newspapers and publishers, imported books and newspapers, and even a " flying university". The situation was similar to that of earlier periods of Polish resistance to foreign occupation, such as the partitions of Poland of the 19th century and the German occupation of 1939–1944, except that the regime made no serious attempt to suppress the opposition. Gierek was interested only in buying off dissatisfied workers and keeping the Soviet Union convinced that Poland was a loyal ally. But the Soviet alliance was at the heart of Gierek's problems: because of Poland's strategic position between the Soviet Union and Germany, the Soviets would never allow Poland to drift out of its orbit, as Yugoslavia and Romania had by this time done. Nor would they allow any fundamental economic reform that would endanger the "socialist system".

In reality, however, Poland was already becoming increasingly capitalistic due to its Western money borrowing. The fact that the West would no longer give Poland credit meant that living standards began to sharply fall again as the supply of imported goods dried up, and as Poland was forced to export everything it could, particularly food and coal, to service its massive debt, which would reach US$23 billion by 1980. By 1978, it was therefore obvious that eventually the regime would again have to raise prices and risk another outbreak of labor unrest.

At this juncture, on October 16, 1978, Poland experienced what many Poles literally believed to be a miracle. The Archbishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope, taking the name John Paul II. The election of a Polish Pope had an electrifying effect on what was by the 1970s the last especially Catholic country in Europe. When John Paul toured Poland in June 1979, half a million people heard him speak in Warsaw, and about a quarter of the entire population of the country attended at least one of his outdoor masses. Overnight, John Paul became the de facto leader of Poland, leaving the regime not so much opposed as ignored. However, John Paul did not call for rebellion; instead, he encouraged the creation of an "alternative Poland" of social institutions independent of the government, so that when the next crisis came, the nation would present a united front.

By 1980, the Communist regime was completely trapped by Poland's economic and political dilemma. The regime had no means of legitimizing itself, since it knew that the PZPR would never win a free election. It had no choice but to make another attempt to raise consumer prices to realistic levels, but it knew that to do so would certainly spark another worker rebellion, much better-organized than the 1970 or 1976 outbreaks. In July 1980, the government gave in and announced a system of gradual but continuous price rises, particularly for meat. A wave of strikes and factory occupations began at once, coordinated from KOR's headquarters in Warsaw.

The regime made little effort to intervene. By this time, the Polish Communists had lost the Stalinist zealotry of the 1940s; they had grown corrupt and cynical during the Gierek years, and had no stomach for bloodshed. The country waited to see what would happen. In early August, the strike wave reached the politically sensitive Baltic coast, with a strike at the Lenin Shipyards in Gdańsk. Among the leaders of this strike was electrician Lech Wałęsa, who would soon become a figure of international importance. The strike wave spread along the coast, closing the ports and bringing the economy to a halt. With the assistance of the activists from KOR and the support of many intellectuals, the workers occupying the various factories, mines and shipyards across Poland came together.

The regime was now faced with a choice between repression on a massive scale and an agreement that would give the workers everything they wanted, while preserving the outward shell of Communist rule. They chose the latter, and on August 31, Wałęsa signed the Gdańsk Agreement with Mieczysław Jagielski, a member of the PZPR Politburo. The Agreement acknowledged the right of Poles to associate in free trade unions, abolished censorship, abolished weekend work, increased the minimum wage, increased and extended welfare and pensions, and abolished Party supervision of industrial enterprises. Only the façade of Party rule was preserved, which was recognized as necessary to prevent Soviet intervention. The fact that all these economic concessions were completely unaffordable escaped attention in the wave of national euphoria that swept the country. The period that started afterwards is often called the "Polish carnival".

The end of Communist rule (1980–1990)

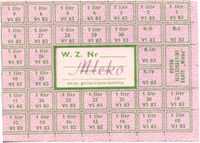

In September 1980, the increasingly frail Gierek was removed from office and replaced as Party leader by Stanisław Kania. Kania made the same sort of promises that Gomułka and Gierek made when they had come to power. But whatever goodwill the new leader gained by these promises was even shorter lived than it had been in 1956 and 1971, because there was no way that the regime could have kept the promises it had made at Gdańsk, even if it wanted to. The regime was still trapped by the conflict between economic necessity and political instability. It could not revive the economy without abandoning state control of prices, but it could not do this without triggering another general strike. Nor could it gain the support of the population through political reform, because of the threat of Soviet intervention. GNP fell in 1979 by 2%, in 1980 by 8% and in 1981 by 15-20% . Public corruption had become endemic and housing shortages and food rationing were just one of many factors contributing to the growing social unrest.

The Gdańsk Agreement, an aftermath of the August 1980 labor strike, were an important milestone. They led to the formation of an independent trade union, " Solidarity" (Polish Solidarność), founded in September 1980 and originally led by Lech Wałęsa. In the 1980s, it helped form a broad anti-Communist social movement, with members ranging from people associated with the Roman Catholic Church to anti-Communist leftists. The union was backed by a group of intellectual dissidents, the KOR, and adhered to a policy of nonviolent resistance. In time, Solidarity became a major Polish political force in opposition to the Communists.

The ideas of the Solidarity movement spread rapidly throughout Poland; more and more new unions were formed and joined the federation. The Solidarity program, although concerned chiefly with trade union matters, was universally regarded as the first step towards dismantling the Communists' dominance over social institutions, professional organizations and community associations. By the end of 1981, Solidarity had nine million members—a quarter of Poland's population, and three times as many members as the PUWP had. Using strikes and other tactics, the union sought to block government initiatives.

On December 13, 1981, claiming that the country was on the verge of economic and civil breakdown, and fearful of Soviet intervention (whether this fear was justified at that particular moment is still hotly disputed by historians), Wojciech Jaruzelski, who had become the Party's national secretary and prime minister that year, started a crack-down on Solidarity, declaring martial law, suspending the union, and temporarily imprisoning most of its leaders. Polish police ( Milicja Obywatelska) and paramilitary riot police (Zmotoryzowane Odwody Milicji Obywatelskiej; ZOMO) suppressed the demonstrators in a series of violent attacks such as the massacre of striking miners in the Kopalnia Wujek. The government banned Solidarity on October 8, 1982. Martial law was formally lifted in July 1983, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place throughout the mid-to-late 1980s.

During the chaotic Solidarity years and the imposition of martial law, Poland entered a decade of economic crisis, officially acknowledged as such even by the regime. Rationing and queuing became a way of life, with ration cards necessary to buy even such basic consumer staples as milk and sugar. Access to Western luxury goods became even more restricted, as Western governments applied economic sanctions to express their dissatisfaction with the government repression of the opposition, while at the same time the government had to use most of the foreign currency it could obtain to pay the crushing rates on its foreign debt.

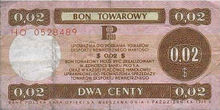

In response to this situation, the government, which controlled all official foreign trade, continued to maintain a highly artificial exchange rate with Western currencies. The exchange rate worsened distortions in the economy at all levels, resulting in a growing black market and the development of a shortage economy. The only way for an individual to buy most Western goods was to use Western currencies, notably the U.S. dollar, which in effect became a parallel currency. However, it could not simply be exchanged at the official banks for Polish złotys, since the government exchange rate undervalued the dollar and placed heavy restrictions on the amount that could be exchanged, and so the only practical way to obtain it was from remittances or work outside the country.

As money came into the country by these channels, the government in turn attempted to gather it up by various means, most visibly by establishing a chain of state-run Pewex stores in all Polish cities where goods could only be bought with hard currency. It even introduced its own ersatz U.S. currency (bony in Polish). These trends led to an unhealthy state of affairs where the chief determinant of economic status was access to hard currency. This situation was incompatible with any remaining ideals of socialism, which were soon completely abandoned.

In this desperate situation, all development and growth in the Polish economy slowed to a crawl. Most visibly, work on most of the major investment projects that had begun in the 1970s was stopped. As a result, most Polish cities acquired at least one infamous example of a large unfinished building languishing in a state of limbo. While some of these were eventually finished decades later, most, such as the Szkieletor skyscraper in Kraków, were never finished at all, wasting the considerable resources devoted to their construction. Polish investment in economic infrastructure and technological development fell rapidly, ensuring that the country lost whatever ground it had gained relative to Western European economies in the 1970s. To escape the constant economic and political pressures during these years, and the general sense of hopelessness, hundreds of thousands of Poles left the country and settled in the West, few of them returning to Poland even after the end of Communism in Poland. Tens of thousands more went to work in countries that could offer them salaries in hard currency, notably Libya and Iraq.

After several years of the situation continuing to worsen, during which time the Communist government unsuccessfully tried various expedients to improve the performance of the economy—at one point resorting to placing military commissars to direct work in the factories—it grudgingly accepted pressures to liberalize the economy. The government introduced a series of small-scale reforms, such as allowing more small-scale private enterprises to function. However, the government also realized that it lacked the legitimacy to carry out any large-scale reforms, which would inevitably cause large-scale social dislocation and economic difficulties for most of the population, accustomed to the limited social safety net that the communist system had provided. For example, when the government proposed to close the Gdańsk Shipyard, a decision in some ways justifiable from an economic point of view but also largely political, there was a wave of public outrage and the government was forced to back down.

The only way to carry out such changes without social upheaval would be to acquire at least some support from the opposition side. The government accepted the idea that some kind of a deal with the opposition would be necessary, and repeatedly attempted to find common ground throughout the 1980s. However, at this point the Communists generally still believed that they should retain the reins of power for the near future, and only allowed the opposition limited, advisory participation in the running of the country. They believed that this would be essential to pacifying the Soviet Union, which they felt was not yet ready to accept a non-Communist Poland.

The constant state of economic and societal crisis meant that, after the shock of martial law had faded, people on all levels again began to organize against the regime. "Solidarity" gained more support and power, though it never approached the levels of membership it enjoyed in the 1980–1981 period. At the same time, the dominance of the Communist Party further eroded as it lost many of its members, a number of whom had been revolted by the imposition of martial law. Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persisted solely as an underground organization, supported by the Church and by funding from the CIA. Starting from 1986, other opposition structures such as the Orange Alternative "dwarf" movement founded by Major Waldemar Fydrych began organizing street protests in form of colorful happenings that assembled thousands of participants and broke the fear barrier which was paralysing the population since the Martial Law. By the late 1980s, Solidarity was strong enough to frustrate Jaruzelski's attempts at reform, and nationwide strikes in 1988 were one of the factors that forced the government to open a dialogue with Solidarity.

The perestroika and glasnost policies of the Soviet Union's new leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, were another factor in stimulating political reform in Poland. In particular, Gorbachev essentially repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine, which had stipulated that attempts by its Eastern European satellite states to abandon Communism would be countered by the Soviet Union with force. This change in Soviet policy, in addition to the hardline stance of US President Ronald Reagan against Soviet military incursions, removed the specter of a possible Soviet invasion in response to any wide-ranging reforms, and hence eliminated the key argument employed by the Communists as a justification for maintaining Communism in Poland.

By the close of the 10th plenary session in December 1988, the Communist Party had decided to approach leaders of Solidarity for talks. From February 6 to April 15, 94 sessions of talks between 13 working groups, which became known as the " Round Table Talks" (Polish: Rozmowy Okrągłego Stołu) radically altered the structure of the Polish government and society. The talks resulted in an agreement to vest political power in a newly created bicameral legislature, and in a president who would be the chief executive.

In April 1989, Solidarity was again legalized and allowed to participate in semi-free elections on June 4, 1989. This election was officially rigged to keep the Communists in power, since only one third of the seats in the key lower chamber of parliament would be open to Solidarity candidates. The other two thirds were to be reserved for candidates from the Communist Party and its two allied, completely subservient parties. The Communists thought of the election as a way to keep power while gaining some legitimacy to carry out reforms. Many critics from the opposition believed that by accepting the rigged election Solidarity had bowed to government pressure, guaranteeing the Communists domination in Poland into the 1990s.

The outcome of the election was largely unpredictable. After all, Poland had not had a truly fair election since the 1920s, so there was little precedent to go by. It was clear that the Communists were unpopular, but there were no hard numbers as to how low support for them would actually fall. The Communist government still had control over most major media outlets and employed sports and television celebrities for candidates, as well as successful local personalities and businesspersons. Some members of the opposition were worried that such tactics would gain enough votes from the less educated segment of the population to give the Communists the legitimacy that they craved.

When the results were released, a political earthquake followed. The victory of Solidarity surpassed all predictions. Solidarity candidates captured all the seats they were allowed to compete for in the Sejm, while in the Senate they captured 99 out of the 100 available seats. At the same time, many prominent Communist candidates failed to gain even the minimum number of votes required to capture the seats that were reserved for them. With the election results, the Communists suffered a catastrophic blow to their legitimacy.

The next few months were spent on political maneuvering. The prestige of the Communists fell so low that the two parties allied with them decided to break away and adopt independent courses. The Communist candidate for the post of Prime Minister, general Czesław Kiszczak, failed to gain enough support in the Sejm to form a government. Although Jaruzelski tried to persuade Solidarity to join the Communists in a "grand coalition", Wałęsa refused. By August of 1989, it was clear that a Solidarity Prime Minister would have to be chosen. Jaruzelski resigned as general secretary of the Communist Party, but found that he was forced to come to terms with a government formed by Solidarity: the Communists, who still had control over state power, were pacified by a compromise in which Solidarity allowed General Jaruzelski to remain head of state. Thus Jaruzelski, whose name was the only one the Communist Party had allowed on the ballot for the presidential election, won by just one vote in the National Assembly, essentially through abstention by a sufficient number of Solidarity MPs. General Jaruzelski became the president of the country, but Solidarity member Tadeusz Mazowiecki became the Prime Minister. The new non-Communist government, the first of its kind in Communist Europe, was sworn into office in September 1989. It immediately adopted radical economic policies, proposed by Leszek Balcerowicz, which transformed Poland into a functioning market economy over the course of the next year.

The striking electoral victory of the Solidarity candidates in these limited elections, and the subsequent formation of the first non-Communist government in the region in decades, encouraged many similar peaceful transitions from Communist Party rule in Central and Eastern Europe in the second half of 1989.

In 1990, Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's president and was succeeded by Wałęsa, who won the 1990 presidential elections. Wałęsa's inauguration as president in December, 1990 is thought by many to be the formal end of the Communist People's Republic of Poland and the beginning of the modern Republic of Poland. The Polish United Workers' Party dissolved in 1990, and the Warsaw Pact was dissolved in the summer of 1991. On October 27, 1991 the first entirely free Polish parliamentary elections since 1928 took place. This completed Poland's transition from Communist Party rule to a Western-style liberal democratic political system.

Changes in Polish society

The Communist years in Poland saw many dramatic changes, both political and social. There were a number of shifts in the social class composition, the role of women in society, and access to health and educational services. With expanded urban industrial opportunities in the early postwar years, agriculture steadily became less popular as an occupation and as a lifestyle. The service sector, like industry, grew rapidly in size in the postwar era, but much less than the service sectors of Western Europe. The result was a postwar exodus from the rural areas and increased urbanization, which split apart the traditional multigenerational families upon which rural society had been based.

In the same period, the central planning system yielded impressive gains in the education level and living standards for much of the new urban industrial workforce. In the early postwar years, only a minority of new recruits from agricultural career were literate, but by the late 1970s only 5% of workers lacked a complete elementary education.

Postwar Poland, like the rest of socialist Eastern Europe, saw growing opportunities for higher education and employment and increased rights for women. In many respects, Poland offered women more opportunities in professional occupations than did many countries in Western Europe. Many professions, such as architecture, engineering and university teaching, employed a considerably higher percentage of women in Poland than in the rest of the West, and a majority of Polish medical students in 1980 were women. Communist propaganda, and sometimes reality itself, has created the stereotype of the "Communist woman worker", similar to the "woman miner" in Silesia.

In the first two decades of Communist rule, the health of Poland's people improved overall, as antibiotics became available and the standard of living rose in most areas. The extension of medical services also contributed to this trend; codifying this trend, the constitution of 1952 guaranteed universal free health care. However, by the 1970s and 1980s, critical national health indicators showed many negative trends, as economic conditions deteriorated, which, combined with small wages in the medical system, led to rampant corruption.

Founded in the late 1950s, the first workers' councils to voice opinions on industrial policy, based on the "Polish October" of 1956, marked a fundamental change in the social status of Polish workers. The increasingly literate leadership of these councils, dominated by the rising numbers of workers that had a secondary education at that time, led to the formidable labor and professional organizations that would gradually come to threaten the socialist order.

Despite the gains in the living standards for much of the growing urban workforce after the World War II, with the increasing influence of outside ideas from the West brought by television, radio (such as Radio Free Europe) and magazines, often smuggled by Poles returning to the country, social dissatisfaction with the regime increased, as people became aware of viable alternatives to their lifestyle. By the 1980s, the modernization of Polish society would lead to a complete restructuring of Poland's political structure.