Go (board game)

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Games

| Go | |

|---|---|

|

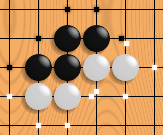

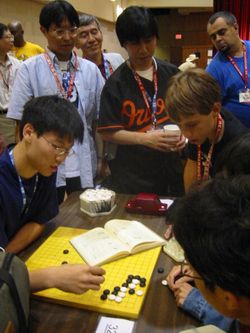

A traditional Go board is wooden, with black painted lines. The stones are lenticular and fit closely together when placed on adjacent intersections. |

|

| Players | 2 |

| Age range | 5+ |

| Setup time | No setup needed |

| Playing time | 10 minutes to 3 hours |

| Rules complexity | Low |

| Strategy depth | Very High |

| Random chance | None |

| Skills required | Strategy, Observation |

Go is a board game for two players. It is also called Weiqi in Chinese (圍棋,围棋), Igo in Japanese ( Kanji: 囲碁), and Baduk in Korean ( Hangul:바둑). Go originated in ancient China before 500 BC. It is now popular throughout the world, especially in East Asia.

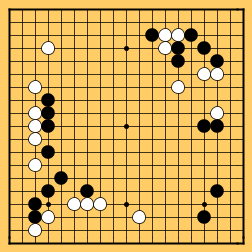

Go is played by alternately placing black and white stones on the vacant intersections of a 19×19 rectilinear grid. A stone or a group of stones is captured and removed if it is tightly surrounded by stones of the opposing colour. The objective is to control a larger territory than the opponent by placing one's stones so they cannot be captured. The game ends and the score is counted when both players consecutively pass on a turn, indicating that neither side can increase its territory or reduce its opponent's; the game can also end by resignation.

Origin of the name

The game is called Go in many languages; this word originated from the Japanese pronunciation "go" of the Chinese characters 棋/碁; in Japanese the name is written 碁. The Chinese name Weiqi (圍棋,围棋) roughly translates as "encirclement chess", "board game of surrounding", or "enclosing game". Its ancient Chinese name is 弈 ( pinyin: yì). The writings 棋/碁 are variants, as seen in the Chinese Kangxi dictionary. The game is most commonly known as 囲碁 (igo) in Japanese. Because Japanese professionals taught the first Western players, the latter naturally used the Japanese name in early German-language and then English-language books and articles about the game.

Terminology

The Japan Go Association ( Nihon Ki-in) has long played a leading role spreading Go outside East Asia, publishing the English-language magazine Go Review in the 1960s, establishing Go Centers in the US and Europe, and often sending professional teachers to Western nations for extended periods. As a result, many Go concepts for which there is no ready English equivalent have become known elsewhere by their Japanese names.

The widespread use of Japanese terminology in the West notwithstanding, Chinese and Korean members of the international Go community, including professionals, continue to advocate for the primacy of terms from their language in common usage. They point out that in recent years, many Chinese and Korean players have also taught Western students. There is also no exact equivalence of concepts in different Asian languages, meaning that Go is still without a standard technical jargon.

In order to differentiate the game from the common English verb " go", the game is sometimes spelt with a capital G; this convention is not however followed in most of the technical literature on the game. An alternative but uncommon spelling is Goe, proposed by Ing Chang-Ki, the late wealthy promoter of Go (particularly in Taiwan and the US), for the same reason. This spelling is not widely used outside events sponsored by the Ing foundation.

History

Some legends trace the origin of the game to Chinese emperor Yao 堯 (2337 - 2258 BC) who designed it for his son, Danzhu, to teach him discipline, concentration, and balance. Other theories suggest that the game was derived from Chinese warlords and generals who used pieces of stone to map out attacking positions, or that Go equipment emerged from divination material. The earliest written references of the game come from the Zuo Zhuan, which describes a man in 548 BC who likes the game, and Book XVII of the Analects of Confucius, compiled sometime after 479 BC.

In China, Go was perceived as the popular game of the aristocratic class while Xiangqi (Chinese chess) was the game of the masses. Go was considered one of the cultivated arts of the Chinese scholar gentleman, along with calligraphy, painting and playing the guqin, together known as 琴棋書畫 ( 四艺, pinyin: Sìyì), or the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar.

Go had reached Japan from China by the 7th century, and gained popularity at the imperial court in the 8th century. By the beginning of the 13th century, Go was played among the general public in Japan.

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu created Japan's first unified national government. Almost immediately, he appointed the then-best player in Japan, Honinbo Sansa, head of a newly founded Go academy (the Honinbo school, the first of several competing schools founded about the same time). These officially recognized and subsidized Go schools greatly developed the level of play, and introduced the martial arts style system of ranking players. Players from the four houses (Honinbo, Yasui, Inoue, Hayashi) competed in the annual castle games for status and the position of Godokoro, or minister of Go. Players like Honinbo Shusaku became national celebrities. The government discontinued its support for the Go academies in 1868 as a result of the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Historically, Go has seen unequal gender participation. However, the creation of new, open tournaments and the rise of strong female players, most notably Rui Naiwei, has in recent years legitimised the strength and competitiveness of emerging female players.

Around 2000, in Japan, the manga (Japanese comic) and anime series Hikaru no Go popularized Go among the youth and started a Go boom in Japan.

Scott A. Boorman's The Protracted Game: A Wei-Chi Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy , likens the game to historical events, saying that the Maoists were better at surrounding territory. Mao Zedong himself was a Go player.

Nature of the game

In game theory terms, Go is a zero-sum, perfect information, deterministic, strategy game, putting it in the same class as chess, checkers (draughts), and reversi (othello) although it is not similar in its play to these. Although the game rules are very simple, the practical strategy is extremely complex.

The game emphasizes the importance of balance on multiple levels, and has internal tensions. To secure an area of the board, it is good to play moves close together; but to cover the largest area one needs to spread out, perhaps leaving weaknesses that can be exploited. Playing too low (close to the edge) secures insufficient territory and influence; yet playing too high (far from the edge) allows the opponent to invade. Many people find Go attractive for its reflection of the conflicting demands of real life.

It has been claimed that Go is the most complex game in the world, on various measures, such as the spread of identifiable levels of skill. Its large board and lack of restrictions allows great scope in strategy and expression of players' individuality. Decisions in one part of the board may be influenced by an apparently unrelated situation in a distant part of the board. Plays made early in the game can shape the nature of conflict a hundred moves later.

The game complexity of Go is such that even an introduction to strategy can fill a book, as evidenced in many introductory books. Go strategy and tactics gives a very brief introduction to the main concepts of Go strategy.

Numerical estimates

On a 19×19 board, there are about 3361×0.012 = 2.1×10170 possible positions, most of which are the end result of about (120!)2 = 4.5×10397 different (no-capture) games, for a total of about 9.3×10567 games. Allowing captures gives as many as

possible games, all of which last for over 4.1×1048 moves. Certainly, no Go game has ever been played twice.

In comparison, the number of legal positions in chess is estimated to be between 1043 and 1050.

Traditional Japanese equipment

Although one could play Go with a piece of cardboard for a board and a bag of plastic tokens, the finest equipment costs thousands of dollars. Many players derive great aesthetic and sensual satisfaction from playing with good equipment.

The traditional Go board (goban in Japanese) is solid wood, from 10 to 18 cm thick, and often stands on its own attached legs. It is preferably made from the rare golden-tinged Kaya tree (Torreya nucifera), with the very best made from Kaya trees up to 700 years old. More recently, the California Torreya (Torreya californica) has been prized for its light colour and pale rings. Other woods often used to make quality table boards include Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata), Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum), and Kauri (Agathis). So-called Shin Kaya is a potentially confusing merchant's term: shin means "new" and "shin kaya" is best translated "faux kaya" — the woods so described are biologically unrelated to Kaya.

Players sit on rice-straw mats ( tatami) on the floor to play. The pleasantly smooth stones (go-ishi) are kept in matching solid wood bowls (go-ke) and are made of clamshell (white) and slate (black). The classic slate is nachiguro stone mined in Wakayama prefecture and the clamshell from the Hamaguri clam. The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the native clams and slow-growing Kaya trees; both must be of sufficient age to grow to the desired size, and they are now extremely rare at the age and quality required, raising the price of such equipment tremendously.

In clubs and at tournaments, where large numbers of sets must be maintained (and usually purchased) by one organization, expensive traditional sets are not usually used. For these situations, table boards (of the same design as floor boards, but only about 2–5 cm thick and without legs) are used, and the stones are made of glass rather than slate and shell. Bowls are often plastic if wooden bowls are not available. Plastic stones could be used, but are considered inferior to glass as they are generally too light, and stick to the fingers even after being released. Most players find that the lower price does not justify this distraction.

Traditionally, the board's grid is 1.5 shaku long by 1.4 shaku wide (455 mm by 424 mm) with space beyond to allow stones to be played on the edges and corners of the grid. This often surprises newcomers: it is not a perfect square, but is longer than it is wide, in the proportion 15:14. Two reasons are frequently given for this. One is that when the players sit at the board, the angle at which they view the board gives a foreshortening of the grid; the board is slightly longer between the players to compensate for this. Another suggested reason is that the Japanese aesthetic finds structures with geometric symmetry to be in bad taste.

Traditional stones are made so that black stones are slightly larger in diameter than white; this is probably to compensate for the optical illusion created by contrasting colours that would make equal-sized white stones appear larger on the board than black stones. The difference is slight, and since its effect is to make the stones appear the same size on the board, it can be surprising to discover they are not.

The bowls for the stones are of a simple shape, like a flattened sphere with a level underside. The lid is loose-fitting and is upturned before play to receive stones captured during the game. The bowls are usually made of turned wood, although small lidded baskets of woven bamboo or reeds make an attractive cheaper alternative.

The traditional way to place a Go stone is to first take a stone from the bowl, gripping it between the index and middle fingers, and then place it directly on the desired intersection. It is permissible to strike the board firmly to produce a sharp click. Many consider the acoustic properties of the board to be quite important. The traditional goban will usually have its underside carved with a pyramid called a heso recessed into the board. Tradition holds that this is to give a better resonance to the stone's click, but the more conventional explanation is to allow the board to expand and contract without splitting the wood. A board is seen as more attractive when it is marked with slight dents from decades (or centuries) of stones striking the surface.

Rules

Basic rules

- Two players, Black and White, take turns placing a stone (game piece) on a vacant point (intersection) of a 19 by 19 board (grid). Black moves first. Other board sizes such as 13x13 and 9x9 may be used for teaching or quick games, but 19x19 is the standard size. Once played, a stone may not be moved to a different point.

- A vacant point adjacent to a stone is a liberty for that stone.

- Adjacent stones of the same colour form a unit that shares its liberties in common, cannot subsequently be subdivided, and in effect becomes a single larger stone.

- Units may be expanded by playing additional stones of the same color on their liberties, or amalgamated by playing a stone on a mutual liberty of two or more units of the same colour.

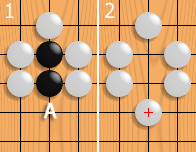

- A unit must have at least one liberty to remain on the board. When a unit is surrounded by opposing stones so that it has no liberties, it is captured and removed from the board.

- If a stone is played where it has no liberties, but it occupies the last liberty of one or more opposing units, then such units are captured first, leaving the newly played stone at least one liberty.

- "Ko rule": A stone cannot be played on a particular point if doing so would recreate the board position that existed after the same player's previous turn.

- A player may pass instead of placing a stone, indicating that he sees no way to increase his territory or reduce his opponent's territory. When both players pass consecutively, the game ends and is then scored.

A player's score is the number of empty points enclosed only by his stones plus the number of points occupied by his stones. The player with the higher score wins. (Note that there are other rulesets that count the score differently, yet almost always produce the same result.) For a more detailed treatment, see Rules of Go.

This is the essence of the game of Go. The risk of capture means that stones must work together to control territory, which makes the gameplay very complex and interesting.

Go allows one to play not only even games (games between players of roughly equal strength) but also handicap games (games between players of unequal strength). Without a handicap, even a slight difference in strength will generally be decisive.

Optional rules

Optional Go rules may set the following:

- compensation points, almost always for the second player, see komi;

- compensation stones placed on the board before alternate play, allowing players of different strengths to play competitively (see Go handicap for more information);

- "superko": the ko rule (a move must not recreate the previous position) is extended to disallow any previous position. This prevents complex repetitive situations ("triple ko", "eternal life", etc.) from cycling indefinitely.

Strategy

Basic strategic aspects include the following:

- Connection: Keeping one's own stones connected means that fewer groups need defense.

- Cut: Keeping opposing stones disconnected means that the opponent needs to defend more groups.

- Life: This is the ability of stones to permanently avoid capture. The simplest way is for the group to surround two "eyes" (separate empty areas), so that filling one eye will not kill the group and therefore be suicidal.

- Death: The absence of life coupled with the inability to create it, resulting in the eventual removal of a group.

- Invasion: Setting up a new living position inside an area where the opponent has greater influence, as a means of balancing territory.

- Reduction: Placing a stone far enough into the opponent's area of influence to reduce the amount of territory he/she will eventually get, but not so far in that it is cut off from friendly stones outside.

The strategy involved can become very abstract and complex. High-level players spend years perfecting understanding of strategy.

Concepts and philosophy

Go is not easy to play well. With each new level (rank) comes a deeper appreciation for the subtlety and nuances involved, and for the insight of stronger players. The acquisition of major concepts of the game comes slowly. Novices often start by randomly placing stones on the board, as if it were a game of chance; they inevitably lose to experienced players who know how to create effective formations. An understanding of how stones connect for greater power develops, and then a few basic common opening sequences may be understood. Learning the ways of life and death helps in a fundamental way to develop one's strategic understanding, of weak groups. It is necessary to play some thousands of games before one can get close to one's ultimate potential Go skill. A player who plays aggressively, is said to display kiai or fighting spirit in the game.

Familiarity with the board shows first the tactical importance of the edges, and then the efficiency of developing in the corners first, then sides, then centre. The more advanced beginner understands that territory and influence are somewhat interchangeable — but there needs to be a balance. It is best to develop more or less at the same pace as the opponent in both territory and influence. This intricate struggle of power and control makes the game highly dynamic.

Often, a comparison of Go and chess is used as a parallel to explain western versus eastern strategic thinking. Go begins with an empty board. It is focused on building from the ground up (nothing to something) with multiple, simultaneous battles leading to a point-based win. Chess, one can say, is in the end centralised, as the predetermined object is to kill one individual piece (the king). Go is quite otherwise: individuals are only significant as they join or help determine the fate of larger forces, and what those are is worked out only as the game proceeds.

A similar comparison has been drawn among Go, chess and backgammon, perhaps the three oldest games that still enjoy worldwide popularity. Backgammon is a "man vs. fate" contest, with chance playing a strong role in determining the outcome. Chess, with rows of soldiers marching forward to capture each other, embodies the conflict of "man vs. man." Because the handicap system tells each Go player where he/she stands relative to other players, an honestly ranked player can expect to lose about half of his/her games; therefore, Go can be seen as embodying the quest for self-improvement — "man vs. self."

Computer software

Software players

Go poses a significant challenge to computer programmers. While there may be only a handful of masters in the world who can beat the best computer chess software, there are millions of people who can beat the best computer Go software. The best computer Go software manages to reach consistently only the range 8–10 kyu, the level a human beginner can hope to reach by studying and playing regularly for some months. Programs for Go are not yet much helped by fast computation. On the other hand, a chess-playing computer, Deep Blue, beat the world champion in 1997. For this reason, many in the field of artificial intelligence consider Go to be a better measure of a computer's capacity for thought than chess.

The reasons why computers are not good at playing Go are attributed to many qualities of the game, including:

- Although there are usually less than 50 playable (meaning acceptable) moves (and not uncommonly even fewer than 10) the area of the board is very large (five times the size of a chess board) and the number of legal moves rarely go below 50. Throughout most of the game the number of legal moves stay at around 150–250, but computers have a hard time distinguishing between good and bad moves.

- Whereas in most games based on capture (e.g. chess, checkers) the game becomes simpler over time as pieces disappear, in Go, a new piece appears every move, and the game becomes progressively more complex, at least for the first 100 ply.

- Unlike other games, a material advantage in Go does not mean a simple way to victory, and may just mean that short-term gain has been given priority.

- The non-local nature of the ko rule has to be kept in mind in advanced play.

- There is a very high degree of pattern recognition involved in human capacity to play well.

Software assistance

Computers become useful when they are used as tools to support Go learners and players in the following ways:

- Internet-based Go servers allow people all over the world to play one another. Online Go playing is becoming popular, with many strong amateur players and pros taking part.

- There are numerous go websites, and a specialist go wiki, Sensei's Library.

- Game records can be stored in files and kept in a database. One can then search the database for a particular opening strategy, or for games by a particular player. Electronic databases now provide a convenient, efficient way to study joseki, fuseki, life and death situations and other problems. This development has had a major impact on the information on high-level play that is generally available.

- Computers make it easy to review and study game records. Many comments and annotated variations can be included in one file. Teachers can review a player's game records and attach variations and comments. Many teachers now use this method online, instructing students they may have never met.

Variants

There are many variations on the basic game of Go. Many of the modern variants are purely for fun, but some were invented with a specific purpose in mind. For example, capture Go is used for introducing the game to beginners, whilst rengo (paired Go) aims at the promotion of the game amongst women. There are also historical regional variations that have now fallen out of fashion, such as Sunjang Baduk and Tibetan Go.

In popular culture

There are some instances in modern culture where Go and its strategies have been used as a literary concept, such as theme. For example, the 1979 novel Shibumi by Trevanian, centers around the game and uses Go metaphors. Go symbolism is used in the Chung Kuo series of novels, and Rick Cook's Limbo System. Other novels that have centered around the game include the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens and Kiriyama Prize winner The Girl Who Played Go by Shan Sa, Nobel prize-winner Yasunari Kawabata's The Master of Go, Sung-Hwa Hong's First Kyu, Scarlett Thomas's PopCo, and Jean-Jacques Pelletier' s Blunt: Les Treize Derniers Jours.

In television, Go appeared in:

- a Nikita story arc with the character "Jurgen".

- the Star Trek: Enterprise episode titled "The Cogenitor", in which Charles Tucker plays Go.

- Andromeda, in which Dylan Hunt and Gaheris Rhade both play a futuristic version of Go.

- in episode 15 of season 3 of 24, with several scenes in an underground Chinese Go club.

- a 1980s TV series called Chessgame with Terence Stamp as a spy master who would spend long periods studying a Go board.

In films Go has appeared in Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, A Beautiful Mind, Pi, Restless, After the Sunset and Hero among many others. The game is featured in the manga and anime series Hikaru no Go and Naruto. At the end of each episode of the Japanese anime version of Hikaru no Go, a three minute segment teaches a concept of Go.

Competitive play

Ranks

In Go, ranks are employed to indicate playing strength. The difference between the amateur ranks is one handicap stone while for professional ranks the difference is roughly 1 stone for every three ranks. For example, if a 5k played a game with a 1k where the 1k gave four handicap stones, the game would be about even whereas if a 9p played a 3p, he would give two handicap stones for a game where both have equal chances.

The rank system is comprised of, from the lowest to highest ranks:

| Rank Type | Range | Stage |

|---|---|---|

| double-digit kyu (級,급) (gup in Korean) | 30–10k | Introductory |

| single-digit kyu | 9–1k | Elementary to Intermediate |

| amateur dan (段,단) | 1–7d (where 8d is special title) | Advanced |

| professional dan (段,단) | 1–9p (where 10p is special title) | Expert |

Time control

Like many other games, a game of Go may be timed using a game clock. Game clocks are often used in tournaments so that all players finish in a timely way and the next round can be paired on time. Players may also use game clocks for casual play, for instance if playing an opponent who is known to play slowly. There are two widely used methods that are associated with Go .

Standard Byo-Yomi: After the main time is depleted, a player has a certain number of time periods (typically around thirty seconds). After each move, the number of time periods that the player took (possibly zero) is subtracted. For example, if a player has three thirty-second time periods and takes thirty or more (but less than sixty) seconds to make a move, he loses one time period. With 60-89 seconds, he loses two time periods, and so on. If, however, he takes less than thirty seconds, the timer simply resets without subtracting any periods. Using up the last period means that the player has lost on time.

Canadian Byo-Yomi: After using all of his/her main time, a player must make a certain number of moves within a certain period of time — for example, twenty moves within five minutes. Typically, players stop the clock, and the player in overtime sets his/her clock for the desired interval, counts out the required number of stones and sets the remaining stones out of reach, so as not to become confused. If twenty moves are made in time, the timer is reset to five minutes again. If the time period expires without the required number of stones having been played, then the player has lost on time.

Further details on this subject can be found at time control.

Top players

Although the game was developed in China, Japan-based players dominated the international Go scene for most of the twentieth century. However, professional players from China such as Nie Weiping (from the 1980s) and South Korea (since the 1990s) have reached even higher levels. Nowadays, top players from China and Korea are of similar strength, but Japan is increasingly lagging behind. Professionals from these three countries regularly compete in a number of national and international Go tournaments. The top Japanese tournaments have a prize purse comparable to that of professional golf tournaments in the United States, while tournaments in China and Korea are less lavishly funded.

Korean players have had an edge in the major international titles, winning 23 tournaments in a row between 2000 and 2002. In the last few years, Korean dominance in international competitions have been increasingly challenged by their Chinese counterparts. Several big name players in South Korea are Lee Chang-ho, Cho Hunhyun, Lee Sedol, Choi Cheol-han, Park Young-Hoon.

The level in other countries has traditionally been much lower (apart from Taiwan), except for some players who had preparatory professional training in Asia. Knowledge of the game has been scanty elsewhere, for most of the game's history. It was not until 2000 that a Westerner, Michael Redmond, achieved the top rank awarded by an Asian Go association, 9th dan. A German scientist, Oscar Korschelt, is credited with the first systematic description of the game in a Western language in 1880; it was not until the 1950s that Western players would take up the game as more than a passing interest. In 1978, Manfred Wimmer became the first Westerner to receive a professional player's certificate from an Asian professional Go association.