First Transcontinental Railroad

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Railway transport

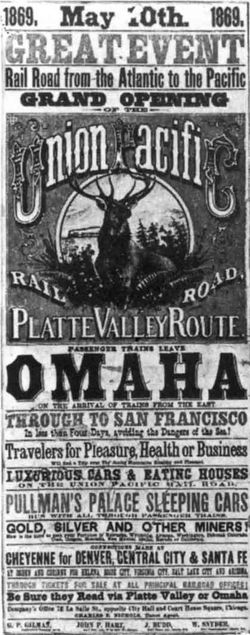

The First Transcontinental Railroad in the United States was built across North America in the 1860s, linking the railway network of the Eastern United States with California on the Pacific coast. Ceremonially completed on May 10, 1869, at the famous " golden spike" event at Promontory Summit, Utah, it created a nationwide mechanized transportation network that revolutionized the population and economy of the American West, catalyzing the transition from the wagon trains of previous decades to a modern transportation system.

Authorized by the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 and heavily backed by the federal government, it was the culmination of a decades-long movement to build such a line and was one of the crowning achievements of the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, completed four years after his death. The building of the railway required enormous feats of engineering and labor in the crossing of plains and high mountains by the Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad, the two privately chartered federally backed enterprises that built the line westward and eastward respectively.

The building of the railroad was motivated in part to bind the Union together during the strife of the American Civil War. It substantially accelerated the populating of the West by white homesteaders, while contributing to the decline of the Native Americans in these regions. In 1879, the Supreme Court of the United States formally established, in its decision regarding Union Pacific Railroad vs. United States (99 U.S. 402), the official "date of completion" of the Transcontinental Railroad as November 6, 1869.

The Central Pacific and the Southern Pacific Railroad combined operations in 1870 and formally merged in 1885. Union Pacific originally bought the Southern Pacific in 1901 but was forced to divest it in 1913; the company once again acquired the Southern Pacific in 1996. Much of the original right-of-way is still in use today and owned by the Union Pacific.

Description

In 1859, the railway network of the eastern United States reached as far west as eastern Iowa. To connect the rail network with the Pacific coast, the Central Pacific Railroad was built from Sacramento, California, eastward and the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, westward until they met. (During construction, the eastern rail network expanded from eastern Iowa to Omaha, Nebraska.)

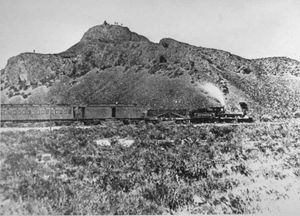

The railroad was considered the greatest technological feat of the 19th century. It served as a vital link for trade, commerce and travel that joined the eastern and western halves of late 19th century United States. The transcontinental railroad quickly ended the romantic yet far slower and more hazardous Pony Express and stagecoach lines which had preceded it. The subsequent march of "Manifest Destiny" and proliferation of the so-called "Iron Horse" across Native American land greatly accelerated the demise of Great Plains Indian culture.

This line was not the first railroad to connect the Atlantic with the Pacific; that honour goes to the Panama Railway, completed in 1855, which ran 48 miles (77 km) across Panama. Other transcontinental railroads followed: the Canadian Pacific Railway, completed in 1885; the Trans-Siberian Railroad, completed in 1905; the first trans-Australian rail line, completed in 1917; and the first north-south trans-Australia line, completed in 2003.

Route

The route followed the main trails used for the opening of the West pioneered by the Oregon, Mormon, California Trails and the Pony Express. Going from Omaha it followed the Platte River through Nebraska, crossed the Rocky Mountains at South Pass and then cut down through northern Utah and Nevada to Sacramento.

When it started it was not directly connected to the Eastern U.S. rail network. Instead trains had to be ferried across the Missouri River. In 1872, the Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge opened and directly connected the East and West.

When construction on the transcontinental line began, the furthest west point for a rail service was the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad connection at the Missouri River at St. Joseph, Missouri. However, Missouri as a border state was considered too strategically vulnerable in the Civil War, and so the decision was made to build the line further north.

The Central Pacific laid 690 miles (1,110 km) of track, starting in Sacramento, California, and continuing through California ( Newcastle and Truckee), Nevada ( Reno, Wadsworth, Winnemucca, Battle Mountain, Elko, Humboldt-Wells), and connecting with the Union Pacific line at Promontory Summit in the Utah Territory. Later, the route was extended to the Alameda Terminal in Alameda, California, and shortly thereafter, to the Oakland Long Wharf in Oakland, California.

The Union Pacific laid 1,087 miles (1,749 km) of track, starting in Omaha, Nebraska, and continuing through Nebraska ( Elkhorn, Grand Island, North Platte, Ogallala, Sidney, Nebraska), the Colorado Territory ( Julesburg), the Wyoming Territory ( Cheyenne, Laramie, Green River, Evanston), the Utah Territory ( Ogden, Brigham City, Corinne), and connecting with the Central Pacific at Promontory Summit.

Laborers

The majority of the Union Pacific track was built by Irish laborers, veterans of both the Union and Confederate armies, and Mormons who wished to see the railroad pass through Ogden and Salt Lake City, Utah. Mostly Chinese ( coolies) built the Central Pacific track. Even though at first they were thought to be too weak or fragile to do this type of work, after the first day in which Chinese were on the line, the decision was made to hire as many as could be found in California (where most were gold miners or in service industries such as laundries and kitchens), plus many more were imported from China. Most of the men received between one and three dollars per day, but the workers from China received much less. Eventually, they went on strike and gained a small increase in salary.

In addition to track laying (which employed approximately 25% of the labor force), the operation also required the efforts of hundreds of blacksmiths, carpenters, engineers, masons, surveyors, teamsters, telegraphers, and even cooks, to name just a few of the trades involved in this monumental task.

History

Pacific Railroad Act

Although Theodore Judah is considered to be the "father" of the First Transcontinental Railroad, Asa Whitney made what some consider the first concerted attempt to get the government to seriously consider such a great project. He was not the first or only man of his time to conceive of a railroad running across the frontier from the Great Lakes to the Pacific coast, but he was the first to lead a team of eight men in June 1845 along the proposed route.

Whitney's team assessed available resources, such as stone and wood, attempted to determine how many bridges, cuts and tunnels would be necessary, and estimated the amount of arable land. Additionally, Whitney traveled widely to solicit support from businessmen and politicians, printed maps and pamphlets, and submitted several carefully considered proposals to Congress, all at his own expense. The Mexican-American War obstructed his efforts over a period of six years.

Theodore Judah was perhaps no more committed than Whitney, but he had advantages and opportunities that Whitney never got. He became the chief engineer for the newly-formed Sacramento Valley Railroad in 1852, surveyed the route for the road, and oversaw its construction. Judah was convinced that from Sacramento, a rail line could be laid over the Sierra Nevada mountains, and he wanted to be the engineer to do it.

Interest payments bankrupted the Sacramento Valley Railroad, though, so Judah had to find another way to build the road. He traveled to Washington, D.C. in 1856, hoping to learn how to lobby Congress for his project. He wrote a 13,000-word proposal in support of a Pacific railroad, had it printed, and distributed it to Cabinent secretaries, congressmen, and other influential people.

Judah was chosen to be the accredited lobbyist for the Pacific Railroad Convention, first assembled in San Francisco in September 1859. Although factional bickering threatened to derail the Convention proceedings, Judah rallied them to adopt his plan to survey, finance, and engineer the road. Judah returned to Washington in December 1859, where he was given an office in the United States Capitol, an audience with President James Buchanan, and he represented the Convention before Congress. Iowa Representative Samuel Curtis introduced a bill in February 1860, which called for finances and land grants to support the Pacific road, but it was not passed by the House until December that year, and came to nothing when it could not be reconciled with rival bills.

Judah returned to California in 1860 and split his time between raising enough money to live and scouting the Sierra Nevada mountains in search of a pass suitable for a railroad, convinced that if he found it, no one could deny the worth of his project. That summer, a local miner, Daniel Strong, had surveyed a route over the Sierras for a wagon road, a route he realized would also suit a railroad. He described his discovery in a letter to Judah, and together they formed an association to solicit subscriptions from local merchants and businessmen to support their paper railroad.

Collis Huntington, a prosperous Sacramento hardware merchant, heard Theodore Judah lecture at the St. Charles Hotel in November 1860, and he invited Judah to his office to hear his proposal in detail. Huntington was savvy enough to realize the importance of a transcontinental railroad to business. He also knew that selling subscriptions door to door was no way to raise money for such a grand enterprise, so he found four partners to invest $1,500 each and form a board of directors: Mark Hopkins, his business partner; James Bailey, a jeweler; Leland Stanford, a grocer and the future governor of California; and Charles Crocker, a dry-goods merchant.

From January or February 1861 until July, the party of ten led by Judah and Strong surveyed the route for the railroad over the Sierra Nevada, through Clipper Gap, Emigrant Gap, Donner Pass, and south to Truckee. While he charted the road's line, Leland Stanford met with President Abraham Lincoln in Washington, and a special congressional session was convened where the Pacific Railway bill was reintroduced by Curtis. Congress was more concerned with issues surround the Civil War, however, and the bill was not passed until the next session.

Judah traveled to Washington in October 1861 to lobby for the Pacific Railroad Act with Aaron Sargent, once a newspaper editor and one of Judah's strongest supporters, now a freshman Congressman assigned to the House Pacific Railroad Committee. Judah was named the committee's clerk. While they helped push the Pacific Railroad bill through committee, Stanford and Crocker traveled to Nevada to secure a franchise from the Nevada legislature to build the Central Pacific through the territory.

The Pacific Railroad bill passed the House of Representatives on May 6, 1862, and the Senate on June 20. Lincoln signed it into law on July 1. The act called for several companies to build the railroad: from the west, the Central Pacific, and from the east, the newly-chartered Union Pacific. Each was required to build only 50 miles (80 km) in the first year; after that, only 50 miles (80 km) more were required each year. Besides land grants along the right-of-way, each railroad was subsidized $16,000 per mile ($9.94/m) built over an easy grade, $32,000 mile ($19.88/m) in the high plains, and $48,000 per mile ($29.83/m) in the mountains. The race was on to see which railroad company could build the longest section of track.

Construction

Because of the nature of the way money was given to the companies building the railroad, they were sometimes known to sabotage each other's railroads to claim that land as their own. When they first came close to meeting, they changed paths to be nearly parallel, so that each company could claim subsidies from the government over the same plot of land. Fed up with the fighting, Congress eventually declared where and when the railways should meet. Survey teams closely followed by work crews from each railroad passed each other, eager to lay as much track as possible. The leading Central Pacific road crew set a record by laying 10 miles (16 km) of track in a single day, commemorating the event with a signpost beside the track for passing trains to see.

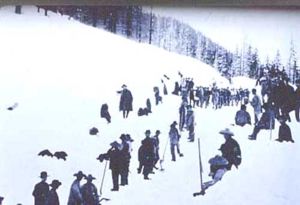

Central Pacific

Six months later, on January 8, 1863 Governor Leland Stanford ceremoniously broke ground in Sacramento, California, to begin construction of the Central Pacific Railroad. The Central Pacific made great progress along the Sacramento Valley. However construction was slowed, first by the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, then by the mountains themselves and most importantly by winter snow storms. As a result, the Central Pacific expanded its efforts to hire immigrant laborers (many of whom were Chinese). The immigrants seemed to be more willing to tolerate the horrible conditions, and progress continued. The increasing necessity for tunneling then began to slow progress of the line yet again. To combat this, Central Pacific began to use the newly-invented and very unstable nitroglycerin explosives—which accelerated both the rate of construction and the mortality of the laborers. Appalled by the losses, the Central Pacific began to use less volatile explosives and developed a method of placing the explosives in which the Chinese blasters worked from large suspended baskets which were then rapidly pulled to safety after the fuses were lit. Construction began again in earnest.

Union Pacific

The major investor in the Union Pacific was Thomas Clark Durant , who had made his stake money by smuggling Confederate cotton with the aid of Grenville M. Dodge. Durant chose routes that would favour places where he held land, and he announced connections to other lines at times that suited his share dealings. Durant paid an associate to submit the construction bid who then handed it over to another company controlled by Durant, Crédit Mobilier. Durant then manipulated the finances and government subsidies, making himself another fortune. Durant hired Dodge as chief engineer and Jack Casement as construction boss.

In the east, the progress started in Omaha, Nebraska, by the Union Pacific Railroad proceeded very quickly because of the open terrain of the Great Plains. However, they soon became subject to slowdowns as they entered Indian-held lands. The Native Americans living there saw the addition of the railroad as a violation of their treaties with the United States. War parties began to raid the moving labor camps that followed the progress of the line. Union Pacific responded by increasing security and by hiring marksmen to kill American Bison—which were both a physical threat to trains and the primary food source for many of the Plains Indians. The Native Americans then began killing laborers when they realized that the so-called "Iron Horse" threatened their existence. Security measures were further strengthened, and progress on the railroad continued.

Completion

Six years after the groundbreaking, laborers of the Central Pacific Railroad from the west and the Union Pacific Railroad from the east met at Promontory Summit, Utah. It was here on May 10, 1869 that Stanford drove the golden spike (which is now located at the Stanford University Museum ) that symbolized the completion of the transcontinental railroad. In perhaps the world's first live mass-media event, the hammers and spike were wired to the telegraph line so that each hammerstroke would be heard as a click at telegraph stations nationwide—the hammerstrokes were missed, so the clicks were sent by the telegraph operator. As soon as the ceremonial spike had been replaced by an ordinary iron spike, a message was transmitted to both the East Coast and West Coast that simply read, "DONE." The country erupted in celebration upon receipt of this message. Complete travel from coast to coast was reduced from six or more months to just one week.

Between 1865 and 1869, the Union Pacific laid 1,087 miles (1,749 km) and the Central Pacific 690 miles (1,110 km) of track. The years immediately following the construction of the railway were years of astounding growth for the United States, largely because of the speed and ease of travel this railroad provided. For example, on June 4, 1876, an express train called the Transcontinental Express arrived in San Francisco via the First Transcontinental Railroad only 83 hours and 39 minutes after it left from New York City. Only ten years before the same journey would have taken months overland or weeks on ship.

Visible remains

Visible remains of the historic line are still easily located—hundreds of miles are still in service today, especially through the Sierra Nevada Mountains and canyons in Utah and Wyoming. While the original rail has long since been replaced because of age and wear, and the roadbed upgraded and repaired, the lines generally run on top of the original, handmade grade. Vista points on Interstate 80 through California's Truckee Canyon provide a panoramic view of many miles of the original Central Pacific line and of the snow sheds which make winter train travel safe and practical.

In areas where the original line has been bypassed and abandoned, primarily in Utah, the road grade is still obvious, as are numerous cuts and fills, especially the Big Fill a few miles east of Promontory. Promontory was bypassed and that portion of the route closed in 1942 and the site ignored for over two decades. In 1965, the site was established as the Golden Spike National Historic Site with a National Park Service visitor centre. The sweeping curve which connected to the east end of the Big Fill now passes a Thiokol rocket research and development facility.

Current passenger service

Amtrak runs a daily service from Emeryville, California ( San Francisco Bay Area) to Chicago, the California Zephyr. The Zephyr consistently uses the original First Transcontinental Railroad track from Sacramento to Winnemucca, Nevada. The Zephyr usually uses the original track on the westbound runs from Winnemucca to Wells, Nevada. The eastbound runs between these towns usually use tracks built by the Western Pacific Railroad. This is because the Union Pacific Railroad now owns both tracks, and it routes trains on either track.