Diplodocus

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Dinosaurs

| iDiplodocus |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Diplodocus skull

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Extinct (fossil)

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

See text. |

Diplodocus ( pronounced /ˌdɪ.pləˈdɔ.kəs/ or /dɪˈplɔd.əkəs/; meaning "double beam") is a genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaur which lived in what is now western North America at the end of the Jurassic Period. The generic name is in reference to its double-beamed chevron bones ( Greek diplos/διπλος meaning 'double' and dokos/δοκος meaning 'wooden beam' or 'bar'). The chevrons, initially believed to be unique to Diplodocus, have since then been discovered in other diplodocids.

Diplodocus, a herbivorous sauropod dinosaur, was one of the more common dinosaurs found in the Upper Morrison Formation, about 150 to 147 million years ago, in an environment and time dominated by giant sauropods , such as Camarasaurus, Barosaurus, Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus . It is among the most easily identifiable dinosaurs, with its classic dinosaur shape, long neck and tail and four sturdy legs. For many years it was the longest dinosaur known. Its great size may have been a deterrent to predators such as Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus.

Description

One of the best known sauropods, Diplodocus was a very large long-necked quadrupedal animal, with a long, whip-like tail. Its forelimbs were slightly shorter than its hind limbs, resulting in a largely horizontal posture. The long-necked, long-tailed animal with four sturdy legs has been mechanically compared with a suspension bridge. In fact, Diplodocus is the longest dinosaur known from a complete skeleton. While dinosaurs such as Seismosaurus (which might be a large Diplodocus) and Supersaurus were probably longer, fossil remains of these animals are only fragmentary.

The skull of Diplodocus was very small, compared to the size of the animal, which could reach up to 27 metres (90 feet), of which 6 metres was neck. Diplodocus had small, 'peg'-like teeth only at the anterior part of the jaws, which were distinctly procumbent . Its braincase was small. The neck was composed of at least fifteen vertebrae and is now believed to have been generally held parallel to the ground and unable to have been elevated much past horizontal .

Diplodocus had an extremely long tail, composed of at around eighty caudal vertebrae, which is almost double the number some of the earlier sauropods had in their tails (such as Shunosaurus with 43), and far more than conteporaneous macronarians had (such as Camarasaurus with 53). There has been speculation as to whether it may have had a defensive or noisemaking function.

The tail may have served as a counterbalance for the neck. The middle part of the tail had 'double beams' (oddly-shaped bones on the underside of the tail), which gave Diplodocus its name. They may have provided support for the vertebrae or perhaps prevented the blood vessels from being crushed if the animal's heavy tail pressed against the ground. These 'double beams' are also seen in some related dinosaurs.

Discovery and species

Several species of Diplodocus were described between 1878 and 1924. The first skeleton was found at Como Bluff, Wyoming by Benjamin Mudge and Samuel Wendell Williston in 1878 and was named Diplodocus longus ("long double-beam"), by palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878. Diplodocus remains have since been found in the Morrison Formation of the western U.S. States of Colorado, Utah, Montana and Wyoming. Fossils of this animal are common, except for the skull, which is often missing from otherwise complete skeletons. Although not the type species, D. carnegiei is the most completely known and most famous due to the large number of casts of its skeleton in museums around the world.

The two Morrison Formation sauropod genera Diplodocus and Barosaurus had very similar limb-bones. In the past, many isolated limb bones were automatically attributed to Diplodocus but may, in fact, have belonged to Barosaurus.

Valid species

- D. longus, the type species, is known from two skulls and a caudal series from the Morrison Formation of Colorado and Utah.

- D. carnegiei, named after Andrew Carnegie, is the best known, mainly due to a near-complete skeleton collected by Jacob Wortman, of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and described and named by John Bell Hatcher in 1901.

- D. hayi, known from a partial skeleton discovered by William H. Utterback in 1902 near Sheridan, Wyoming, was described in 1924.

- D. hallorum better known as Seismosaurus hallorum. A presentation at the annual conference of the Geological Society of America, in 2004, made a case for Seismosaurus, discovered in 1979 and recognised as a separate genus in 1991, to be reassigned as a species of Diplodocus, namely D. hallorum.

Nomina dubia (Dubious species)

- D. lacustris is a nomen dubium, named by Marsh in 1884, from remains of a smaller animal from Morrison, Colorado. These remains are now believed to have been from an immature animal, rather than from a separate species.

Palaeobiology

Due to a wealth of skeletal remains, Diplodocus is one of the best studied dinosaurs. Many aspects of its lifestyle have been subject to various theories over the years. Marsh and then Hatcher assumed the animal was aquatic, due to the position of its nasal openings at the apex of the cranium. A classic 1910 reconstruction by Dr. Oliver P. Hay depicts two Diplodocus with splayed lizard-like limbs on the banks of a river. Dr. Hay made an argument in favour for Diplodocus having a sprawling, lizard-like gait with widely-splayed legs, and was supported by Dr. Gustav Tornier. However, this hypothesis was put to rest by Dr. W. J. Holland, who demonstrated that a sprawling Diplodocus would have needed a trench to pull its belly through.

The idea of an aquatic existence was later debunked, as the water pressure on the chest wall of Diplodocus was proven to have been too great for the animal to have breathed. Since the 1970s, general consensus has the sauropods as firmly terrestrial animals, browsing on trees. Later still, interestingly, with the preceding view of its possible preference for water plants there is a view of a likely riparian habitat for Diplodocus, echoing the original aquatic theory.

Neck

At first, diplodocids were often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to graze from tall trees. More recently, scientists have argued that the heart would have had trouble sustaining sufficient blood pressure to oxygenate the brain. Furthermore, more recent studies have shown that the structure of the neck vertebrae would not have permitted the neck to bend far upwards. Interestingly, the range of movement of the neck would have allowed the head to graze below the level of the body, leading scientists to speculate on whether Diplodocus grazed on submerged water plants, from riverbanks. This concept of the feeding posture is supported by the relative lengths of front and hind limbs. Furthermore, its peglike teeth may have been used for eating soft water plants.

As with the related genus Barosaurus, the very long neck of Diplodocus is the source of much controversy amongst scientists. A 1992 Columbia University study of Diplodocid neck structure indicated that the longest necks would have required a 1.6 ton heart. The study proposed that animals like these would have had rudimentary auxiliary 'hearts' in their necks, whose only purpose was to pump blood up to the next 'heart' (Lambert).

Spines

Recent discoveries have suggested that Diplodocus and other diplodocids may have had narrow, pointed keratinous spines lining their back, much like those on an iguana. This radically different look has been incorporated into recent reconstructions, notably Walking with Dinosaurs. It is unknown exactly how many diplodocids had this trait.

Trunk

There has been speculation over whether the high nasal openings in the skull meant that Diplodocus may have had a trunk. A recent study surmised there was no paleoneuroanatomical evidence for a trunk. It noted that the facial nerve in an animal with a trunk, such as an elephant, is large as it innervates the trunk. The evidence is that it is very small in Diplodocus. Studies by Lawrence Witmer (2001) indicated that, while the nasal openings were high on the head, the actual, fleshy nostrils were situated much lower down on the snout. .

Growth rate

Following a number of bone histology studies, Diplodocus, along with other sauropods, grew at a very fast rate, reaching sexual maturity just over a decade, though continuing to grow throughout their lives. Previous thinking held that sauropods would keep growing slowly throughout their lifetime, taking decades to reach maturity.

Diet

Diplodocus had highly unusual teeth compared to other sauropods. The crowns were long and slender, elliptical in cross-section, while the apex forms a blunt triangular point. The most prominent wear facet is on the apex, though unlike all other wear patterns observed within sauropods, Diplodocus wear patterns are on the labial (cheek) side of both the upper and lower teeth. What this means is Diplodocus and other diplodocids had a radically different feeding mechanism than other sauropods. Unilateral branch-stripping is the most likely feeding behaviour of Diplodocus , as it explains the unusual wear patterns of the teeth (coming from tooth-food contact). In unilateral branch-stripping one tooth row would have been used to strip foliage from the stem, whilst the other would act as a guide and stabiliser.

With a laterally and dorsoventrally flexible neck, and the possibilty of using its tail and rearing up on its hind limbs (tripodal ability), Diplodocus would have had the ability to browse at many levels (low, medium, and high), up to approximately 12 metres from the ground.

Classification

Diplodocus is both the type genus of, and gives its name to Diplodocidae, the family in which it belongs. Members of this family, while still massive, are of a markedly more slender build compared with other sauropods such as the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs. All are characterised by long necks and tails and a horizontal posture, with forelimbs shorter than hindlimbs. Diplodocids flourished in the Late Jurassic of North America and possibly Africa and appear to have been replaced ecologically by titanosaurs during the Cretaceous.

A subfamily, Diplodocinae, was erected to include Diplodocus and its closest relatives, including Seismosaurus, which may belong to the same genus, and Barosaurus. More distantly related is the contemporaneous Apatosaurus, which is still considered a diplodocid although not a diplodocine, as it is a member of the subfamily Apatosaurine. The Portuguese Dinheirosaurus and the African Tornieria have also been identified as close relatives of Diplodocus by some authors.

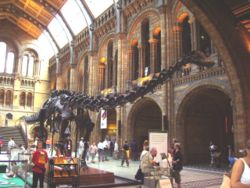

In popular culture

Mounted Casts of Diplodocus skeletons are displayed in many museums worldwide, including an unusual D. hayi in the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and D. carnegiei in the Natural History Museum in London, the Natural Science Museum in Madrid, Spain, the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and, of course, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. A mounted skeleton of D. longus is at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D. C..

Diplodocus was featured in the second episode of the award-winning BBC television series Walking With Dinosaurs. The episode "Time of the Titans" follows the life of a simulated Diplodocus 152 million years ago.

In the animated film The Land Before Time VI: The Secret of Saurus Rock, the character "Doc" (presumably short for Diplodocus), voiced by Kris Kristofferson, was a Diplodocus; in contrast to the "long-neck" protagonists, which were Apatosaurus.

Diplodocus had cameo appearances in The Land That Time Forgot and in The Lost World (2001).