Albrecht Dürer

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mathematicians

Albrecht Dürer (äl'brekht dür'ur) ( May 21, 1471 – April 6, 1528) was a German painter, printmaker, mathematician, and, with Rembrandt and Goya, the greatest creator of old master prints. Born and died in Nuremberg, Germany, he is best known for his prints often done in series, including the Apocalypse (1498) and his two series on the passion of Christ, the Great Passion (1498–1510) and the Little Passion (1510–1511). Dürer's best known individual engravings include Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), Saint Jerome in his Study (1514) and Melencolia I (1514), which has been the subject of the most analysis and speculation. With his Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1497–1498), from the Apocalypse series, it is his most iconic image, followed by his " Rhinoceros" and his numerous painted self-portraits.

Early life

Dürer was born on May 21, 1471, the third child and second son of fourteen to eighteen children. His father was a successful goldsmith, named Ajtósi, who had moved in 1455 to Nuremberg from Ajtós, near Gyula in Hungary. The German name "Dürer" is derived from the Hungarian "Ajtósi". Initially it was "Thürer", meaning doormaker which is "ajtós" in Hungarian (from "ajtó" meaning door). The name "Thürer" became "Dürer"; a door featured in the coat-of-arms the family acquired. Albrecht Ajtósi-Dürer the Elder married Barbara Holper, from a prosperous Nuremberg family, in 1467.

His godfather was Anton Koberger, who in the year of Dürer's birth ceased goldsmithing to become a printer and publisher. He quickly became the most successful publisher in Germany, eventually owning twenty-four printing-presses and having many offices in Germany and abroad. His most famous publication was the Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493 in German and Latin editions, with and an unprecedented 1,809 woodcut illustrations (many repeated uses of the same block) by the Wolgemut workshop.

It is fortunate that Dürer left some autobiographical notes, and also became very famous by his mid-twenties, so that his life is well documented from a number of sources. After a few years of school, Dürer started to learn the basics of goldsmithing and drawing from his father. Though his father wanted him to continue to train as a goldsmith, he showed such a precocious talent in drawing that he started as an apprentice to Michael Wolgemut at the age of 15 in 1486. A superb self-portrait drawing in silverpoint is dated 1484 ( Albertina, Vienna) - "when I was a child" as his later inscription on it says. Wolgemut was the leading artist in Nuremberg at the time, with a large workshop producing a variety of works of art, including woodcuts for books. Nuremberg was a prosperous city, a centre for publishing and many luxury trades. It had strong links with Italy, especially Venice, a relatively short distance across the Alps.

Gap year, or four

After completing his term of apprenticeship in 1489, Dürer followed the common German custom of taking a "wanderjahre" - in effect a gap year. However Dürer was away nearly four years, travelling to Germany, Switzerland, and probably the Netherlands. To his great regret, he missed meeting Martin Schongauer, the leading engraver of Northern Europe, who had died shortly before Dürer's arrival. However he was very hospitably treated by Schongauer's brother and seems to have acquired at this point some works by Schongauer that he is known to have owned. His first self-portrait ( Louvre) was painted in Strasbourg, probably to be sent back to his fiancé in Nuremberg.

Marriage and first visit to Italy

Very soon after his return to Nuremberg, on July 7, 1494, Dürer was married, following an arrangement made during his absence, to Agnes Frey, the daughter of a prominent brassworker (and amateur harpist) in the city. The nature of his relationship with his wife is unclear, but it would not seem to have been a love-match, and his portraits of her lack warmth. They had no children. Within three months Dürer left again for Italy, alone, perhaps stimulated by an outbreak of plague in Nuremberg. He made watercolour sketches as he travelled over the Alps, some of which have survived, and others of which can be deduced from the accurate landscapes of real places in his later work, for example his engraving Nemesis. These are the first pure landscape studies known in Western art.

In Italy, he went to Venice to study the more advanced artistic world there. Through Wolgemut's tutelage, Dürer had learned how to make prints in drypoint and design woodcuts in the German style. based on Martin Schongauer and the Housebook Master.. He would also have had access to some Italian works in Germany, but the two visits he made to Italy had an enormous influence on him. He wrote that Giovanni Bellini was the oldest and still the best of the artists in Venice. His drawings and engravings show the influence of others notably Antonio Pollaiuolo with his interest in the proportions of the body, Mantegna, Lorenzo di Credi and others. Dürer probably also visited Padua and Mantua on this trip.

Return to Nuremberg

On his return to Nuremberg in 1495, Dürer opened his own workshop (being married was a requirement for this). Over the next five years his style increasingly worked Italian influences into underlying Northern forms. Dürer lost his parents during the following years, his father in 1502 and his mother in 1513. His best works in the first years were his woodcut prints, mostly religious, but including secular scenes like The Mens Bath-house (c1496). These were larger than the great majority of German woodcuts hitherto, and far more complex and balanced in composition.

It is now thought unlikely that Dürer cut any of the woodblocks himself; this was left for a specialist craftsman. But his training in Wolgemut's studio, which made many carved and painted altarpieces, and both designed and cut woodblocks for woodcut , evidently gave him great understanding of what the technique could be made to produce, and how to work with blockcutters. Dürer either drew his design directly onto the woodblock itself, or glued a paper drawing to the block. Either way his drawing was destroyed during the cutting of the block.

His famous series of sixteen great designs for the Apocalypse, are dated 1498. He made the first seven scenes of the Great Passion in the same year, and a little later a series of eleven on the Holy Family and saints. Around 1503–1505 he produced the first seventeen of a set illustrating the life of the Virgin, which he did not finish for some years. Neither these nor the Great Passion were published as sets until several years later, but prints were sold individually in considerable numbers.

Over the same period Dürer trained himself in the difficult art of the use of the burin to make engravings; perhaps he had made a start on this during his early training with his father. The first few were relatively unambitious, but by 1496 he was able to produce the masterpiece of the Prodigal Son which Vasari singled out for praise some decades later, noting its Germanic quality. He was soon producing some spectacular and original images, notably Nemesis (1502), The Sea Monster (1498) and St Eustace (1501), with a highly detailed landscape background, and beautiful animals. He made a number of Madonnas, single religious figures, and small scenes with comic peasant figures. Prints are highly portable, and these works made Dürer famous throughout the main artistic centres of Europe within a very few years.

The Venetian artist Jacopo de Barbari, whom Dürer had met in Venice, visited Nuremberg in 1500, and Dürer says that he learned from him much about the new developments in perspective, anatomy and proportion, although de Barberi would not explain everything he knew. Dürer therefore began his own studies, which would be a lifelong preoccupation. A series of extant drawings show Dürer's experiments in human proportion, leading to the famous engraving of Adam and Eve (1504); showing his subtlety at using the burin in the texturing of flesh surfaces.

Dürer made large numbers of preparatory drawings, especially for his paintings and engravings, and many survive, most famously the Praying Hands (1508 Albertina, Vienna), a study for an apostle in the Heller altarpiece. He also continued to make images in watercolour and bodycolour (usually combined), including a number of exquisite still-lifes of pieces of meadow or animals, including his " Hare" (1502, Albertina, Vienna).

Second visit to Italy

In Italy, he turned again to painting, at first producing a series of works by tempera-painting on linen, including portraits and altarpieces, notably the Paumgartner altarpiece and the Adoration of the Magi. In early 1506, he returned to Venice, and stayed there until the spring of 1507. By this time Dürer's engravings had attained great popularity, and had begun to be copied. In Venice he was given a valuable commission from the emigrant German community for the church of St. Bartholomew. The picture painted by Dürer was closer to the Italian style—the Adoration of the Virgin, also known as the Feast of Rose Garlands; it was subsequently acquired by the Emperor Rudolf II and taken to Prague. Other paintings Dürer produced in Venice include The Virgin and Child with the Goldfinch, a Christ disputing with the Doctors (supposedly produced in a mere five days) and a number of smaller works.

Nuremberg and the masterworks

Despite the regard in which he was held by the Venetians, Dürer was back in Nuremberg by mid-1507. He remained in Germany until 1520. His reputation had spread all over Europe. He was on terms of friendship or friendly communication with most of the major artists of Europe, and exchanged drawings with Raphael.

The years between his return from Venice and his journey to the Netherlands are divided according to the type of work with which he was principally occupied. The first five years, 1507–1511, are pre-eminently the painting years of his life. In them, working with a vast number of preliminary drawings and studies, he produced what have been accounted his four best works in painting: Adam and Eve (1507), Virgin with the Iris (1508), the altarpiece the Assumption of the Virgin (1509), and the Adoration of the Trinity by all the Saints ( 1511). During this period he also completed the two woodcut series of the Great Passion and the Life of the Virgin, both published in 1511 together with a second edition of the Apocalypse series.

He complained that painting did not make enough money to justify the time spent, when compared to his prints, and from 1511 to 1514 concentrated on printmaking, in woodcut and especially engraving. The major works he produced in this period were the thirty-seven woodcut subjects of the Little Passion, published first in 1511, and a set of fifteen small engravings on the same theme in 1512. In 1513 and 1514 appeared the three most famous of Dürer's engravings , The Knight, Death, and the Devil (or simply The Knight, as he called it, 1513), the enigmatic and much analysed Melencolia I and St. Jerome in his Study (both 1514).

In ' Melencolia I' appears a 4th-order magic square which is believed to be the first seen in European art. The two numbers in the middle of the bottom row give the date of the engraving: 1514.

Main Article: Dürer's Rhinoceros In 1515, he created a woodcut of a Rhinoceros which had arrived in Lisbon from a written description and brief sketch, without ever seeing the animal depicted. Despite being relatively inaccurate (the animal belonged to a now extinct Indian species), the image has such force that it remains one of his best-known, and was still being used in some German school science text-books early last century.

In the years leading to 1520 he produced a wide range of works, including portraits in tempera on linen in 1516, engravings on many subjects, a few experiments in etching on plates of iron, and parts of the Triumphal Arch and the Triumphs of Maximilian which were huge propaganda woodcut projects commissioned by Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. He drew marginal decorations for some pages of a copy of the Emperor's printed prayer book, which were hardly known until facsimiles were published in 1808 (the first book published in lithography ). These show a lighter, more fanciful, side to Dürer's art, as well as his usual suberb draftsmanship. He also drew a portrait of the Emperor Maximilian shortly before his death in 1519.

Journey to the Netherlands and beyond

In the summer of 1520 the desire of Dürer to renew the Imperial pension Maximilian had given him (typically instructing the City of Nuremberg to pay it) and to secure new patronage following the death of Maximilian and an outbreak of sickness in Nuremberg, gave occasion to his fourth and last journey. Together with his wife and her maid he set out in July for the Netherlands in order to be present at the coronation of the new Emperor Charles V. He journeyed by the Rhine to Cologne, and then to Antwerp, where he was well received and produced numerous drawings in silverpoint, chalk or charcoal. Besides going to Aachen for the coronation, he made excursions to Cologne, Nijmegen, 's-Hertogenbosch, Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Zeeland. In Brussels he saw "the things which have been sent to the king from the golden land" - the Aztec treasure that Hernán Cortés had sent home to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V following the fall of Mexico. Dürer wrote that this trove "was much more beautiful to me than miracles. These things are so precious that they have been valued at 100,000 florins".

He took a large stock of prints with him, and wrote in his diary who he gave, exchanged or sold them to, and for how much. This gives rare information on the monetary value placed on old master prints at this time; unlike paintings their sale was very rarely documented. He finally returned home in July 1521, having caught an undetermined illness which afflicted him for the rest of his life, and greatly reduced his rate of work.

Final years in Nuremberg

Back in Nuremberg, Dürer began work on a series of religious pictures. Many preliminary sketches and studies survive, but no paintings on the grand scale were ever carried out. This was due in part to his declining health, but more because of the time he gave to the preparation of his theoretical works on geometry and perspective, the proportions of men and horses, and fortification. Though having little natural gift for writing, he worked hard to produce his works.

The consequence of this shift in emphasis was that in the last years of his life Dürer produced, as an artist, comparatively little. In painting there was a portrait of Hieronymus Holtzschuher, a Madonna and Child (1526), a Salvator Mundi (1526) and two panels showing St. John with St. Peter in front and St. Paul with St. Mark in the background. In copper-engraving Dürer produced only a number of portraits, those of the cardinal-elector of Mainz (The Great Cardinal), Frederick the Wise, elector of Saxony, and his friends the humanist scholar Willibald Pirckheimer, Philipp Melanchthon and Erasmus of Rotterdam.

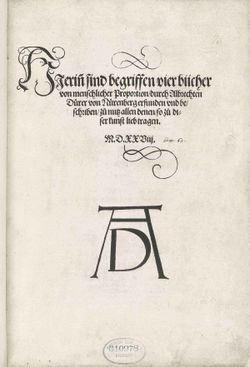

Despite complaining of his lack of formal education, especially in the classical languages, Dürer was greatly interested in intellectual matters, and learned much from his great friend Willibald Pirckheimer , who he probably consulted as to the content of many of his images. He also got great satisfaction from his friendship and correspondence with Erasmus and other scholars. Of his books, Dürer succeeded in finishing and producing two during his lifetime. One on geometry and perspective, The Painter's Manual (more literally the Instructions on Measurement) was published at Nuremberg in 1525, and is the first book for adults to be published on mathematics in German. His work on fortification was published in 1527, and his work on human proportion was brought out in four volumes shortly after his death in 1528 at the age of 56.

It is clear from his writings that Dürer was highly sympathetic to Martin Luther, and he may have been influential in the City Council declaring for Luther in 1525. However, he died before religious divisions had hardened into different churches, and may well have regarded himself as a reform-minded Catholic to the end.

He left an estate valued at 6,874 florins - a considerable sum. His large house, where his workshop also was, and his widow lived until her death in 1537, remains a prominent Nuremberg landmark, and is now a museum.

Legacy

Dürer exerted a huge influence on the artists of succeeding generations; especially on printmaking, the medium through which his contemporaries mostly experienced his art, as his paintings were mostly either in private collections or in a few cities. His success in spreading his reputation across Europe through prints was undoubtedly an inspiration for major artists like Raphael, Titian and Parmigianino who entered into collaborations with printmakers to publicise their work beyond their local region.

His work in engraving seems to have had an intimidating effect on his German successors, the Little Masters, who attempted few large engravings, but continued Dürer's themes in tiny, rather cramped, compositions. The early Lucas van Leiden was the only Northern engraver to successfully continue to produce large engravings in the first third of the century. The generation of Italian engravers who trained in the shadow of Dürer all directly copied either parts of his landscape backgrounds ( Giulio Campagnola and Christofano Robetta), or whole prints ( Marcantonio Raimondi and Agostino Veneziano). However, Dürer's influence became less dominant after about 1515, when Marcantonio perfected his new engraving style, which in turn went over the Alps to dominate Northern engraving also.

In painting, Dürer had relatively little influence in Italy, where probably only his altarpiece in Venice was to be seen, and his German successors were less effective in blending German and Italian styles.

His intense and self-dramatising self-portraits have continued to have huge influence up to the present, and can perhaps be blamed for some of the wilder excesses of artist's self-portraiture, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

He has never fallen from critical favour, and there were particular revivals of interest in him in Germany in the " Dürer Renaissance" of c1570-c1630, in the early nineteenth century, and in German Nationalism from 1870-1945.

Books

- Giulia Bartrum, Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy, British Museum Press, 2002, ISBN 0714126330

- Walter L. Strauss (Editor), The Complete Engravings, Etchings and Drypoints of Albrecht Durer,

Dover Publications, 1973 ISBN 0486228517 - still in print in pb, excellent value.

- Wilhelm Kurth (Editor), The Complete Woodcuts of Albrecht Durer, Dover Publications, 2000, ISBN 0486210979 - still in print in pb, excellent value