The purpose of this blog post depends on the reaction you had while reading the question in the title. If you hesitated, I want to convince you that maybe you should be doing research about YouTube. If you are already interested, and I hope you are (always easier to preach to the choir), I want to discuss the main challenge involved with studying YouTube, and then discretely introduce YouNiverse 🚀, our new dataset paper which can help you with that.

Why should you care about YouTube?

YouTube is a big deal. In 2018 survey by Pew, 54% of adult U.S. internet users said that “the platform was somewhat or very important in helping them understand what is happening in the world.” Also, the role of the platform is by no means limited to the United States. In Brazil, where I was born, content creators from YouTube have been elected for office, played an important role in informing the public amidst the pandemic, and even dominated bookshelves with books aimed at children and teenagers (I remember once I went with my dad to a bookstore and he was in total disbelief that half the books on display were about minecraft). If this flurry of facts was not enough to convince you, in what follows, I give you my best (buzzfeed-style) effort to summarize reasons why you should care. In the process, I hope to introduce you to some of the work being done on YouTube, and the folks behind it.

#1 YouTube is the birthplace of “influencer culture”

YouTuber is the place of birth of the “influencer” culture that has spread to so many other social networks, including Instagram, TikTok and Twitch. As Chris Stokel-Walker writes in his great book “YouTubers: How YouTube shook up TV and created a new generation of stars”:

Until the early 2000s, there was ‘us’ - the viewers […] - and ‘them:’ the Hollywood celebrities […]. But with YouTube, it was possible to create our own champions - and they looked like us. (…)

For good or bad, influencers play a big role in what happens on the internet, and studying YouTube can be a useful way to understand how these individuals shape our information ecosystem.

#2 YouTube plays a big role in politics

All across the world, YouTube is a premier venue for political content. Videos range from “Social Justice Warriors” getting “owned” by angry commentators to intricate 40-minutes video essays discussing Fascism. According to Rebecca Lewis, some political YouTuber differentiate themselves from the mainstream media by adopting micro-celebrity practices that stress relatability, authenticity, and accountability (see her paper). These practices would help YouTubers push alternative political narratives that often flirt with fringe ideologies.

My previous research, has tracked how users migrated from channels espousing contrarian viewpoints to overtly white-supremacist ones. A phenomenon discussed by Rebecca herself in her previous work, and illustrated perfectly by the tale of Caleb Cain, a college dropout who told The New York Times how he was radicalized in the platform. Although YouTube has taken steps to minimize extremist content from flourishing in the platform, the problem does not seem to be quite over yet. More recently, a team of brilliant academics (which you can follow on Twitter: Brendan Nyhan, Annie Y. Chen, Jason Reifler, Ronald Robertson and Christo Wilson) has partnered with ADL to collect user logs from April to October 2020 with a custom made browser extension. Surprisingly, they find that extreme content is still quite prevalent in the platform (source).

#3 YouTube is the world largest “algorithmic information market”

I have been kinda obsessed with this idea since I read “Right-Wing YouTube: A Supply and Demand Perspective” by Kevin Munger and Joseph Phillips. I’ve written half-baked things about this before (here and here), but the gist of it can be obtained from the following excerpt from the paper by Munger and Phillips:

A political economy of the production of political YouTube videos is essential for understanding why these videos exist. The platform has blown past the model where people simply upload videos that had been produced for other purposes; the current concern about YouTube extremism deals almost exclusively with videos produced explicitly to be shared on YouTube. “Creators” upload videos to their “channel” with the hopes of developing a devoted fanbase that they can use to “monetize” their videos.

Their insight applies to YouTube more broadly, and not only to political content. A (still) poorly explored direction that I find fascinating would be to broadly characterize how content creators “compete” for users’ attention. Note that this competition is mediated not by “prices”, as in regular markets, but by powerful recommendation algorithms which can rule your video appropriate or not for the masses (sometimes pretty arbitrarily, as any YouTuber will gladly tell you).

#4 YouTube is where parents go for kid’s content

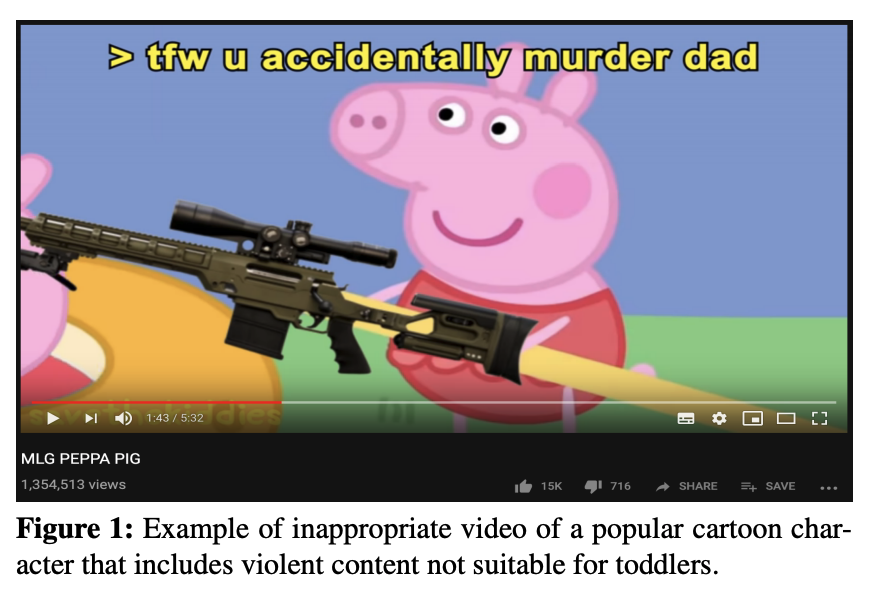

Baby shark has (worryingly?) been viewed 8 million times by children all around the globe. And while YouTube holds content with the potential to inspire kids and teenagers (with awesome channels such as Smarter Every Day, Mark Robber, and my Brazilian favorite, Manual do Mundo), it also has historically hosted content that was ridiculously inappropriate for kids. Superstar iDrama researchers Konstantinos and Antonis have looked into this phenomena in their paper “Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Disturbing Content on YouTube”, which I remember vividly due to the funny lead image:

Moving forward, studying kids content on YouTube is not only a fruitful venue to understand the complex interaction between Big Tech and strict regulation (as shown by this 170M FTC lawsuit), but may also yield real-world impact, preventing the exposure of inappropriate content towards the little ones.

#5 YouTube is an important cultural archive of our time

Last but not least, the vastness of YouTube’s archive creates not only dangerous rabbit holes but also insightful and interesting ones. For me, no video represents the potential of YouTube as a cultural archive as David Bull’s “Remembering a carver - Ito Susumu”. David, a charmingly calm Canadian in his 60s, recalls his interactions with a master woodblock printmaker, Ito Susumu. In the video, David tells how he went on to learn some of Susumu’s carving “secrets” and, in the meantime, sheds light on the life of one of his most admired artists.

The most impressive thing about the video is not only how magnetic this seemingly mundane tale is, but the attention that it received (2 million views!). The video (and others equally fascinating ones) propelled David to YouTube stardom and enabled him to spread his art all across the world through crowdsourcing campaigns.

What are the challenges in studying YouTube?

Okay, so let’s assume I convinced you that YouTube is important. This means it must be one of the most studied social networks, right? Wrong! Consider for example ICWSM: the International Conference on Web and Social Media. How many papers do you think have been published about YouTube there between 2009 and 2020? The answer is 22 (according to Microsoft Academic)! Now let’s consider Twitter, a social network with around 6 times fewer users than YouTube (source). How many papers do you think there are? 145! (Again, according to Microsoft Academic)

Why is that? One could argue that Twitter is more important because of all the fights that happen there, or because of all the journalists and politicians that use the platform. But I can give you simpler and more insightful answer: doing research on Twitter is much easier! Compared to YouTube, Twitter data is simpler to analyze and systematically obtain. For instance, if you want to obtain a random sample of Tweets mentioning COVID-19, you can easily user Twitter’s streaming API to do so. Meanwhile, if you want to obtain a random sample of videos mentioning COVID-19 on YouTube, good luck!

This was not always the case. In a 2007 paper “I tube, you tube, everybody tubes”, Mia Cha et al. did a huge crawl of YouTube. Back then, YouTube would give you an indexed list of all content available on the platform! Wild times. Since then, things have gotten much harder:

-

The platform’s catalog is orders of magnitude larger than it was back in 2007.

-

There is no systematic way to obtain a random sample of videos or channels (that is not extremely inefficient).

-

Application Programming Interfaces do exist, but have been severely limited in recent times.

Thus, when researchers study the platform, they resort to a variety of heuristics such as using the Website’s search functionality, snowball sampling recommendations, and selecting links that are shared in other platforms (e.g., Twitter). These sampling strategies involve a great amount of extra work and often hinder the generalizability of studies (since research is carried with little knowledge about the representativeness of the data analyzed).

YouNiverse 🚀

Since data collection seems to be the big block, Bob and I decided to release YouNiverse: a large scale dataset on YouTube that will empower the community to do research with and about YouTube. YouNiverse contains many moving parts, including video metadata for over 72.9 million videos. You can read the paper in arXiv and download the data on Zenodo, but to get the gist of it, here goes a YouTube video for your watch list!