[This post describes research from the paper Population-scale dietary interests during the COVID-19 pandemic published in Nature Communications. Code and data are available on GitHub.]

Very early on in the course of the pandemic, there were warnings about the potential side-effects of the lockdowns, such as alcohol misuse and weight-gain. We started working on this project believing that it would be interesting and important to understand changes in food-related habits brought by the pandemic.

There were also anecdotal reports about the increased interest in baking, sourdough bread, comfort food. Banana bread had a serious moment right there!

Our guiding question in this work was: How did dietary interests shift during COVID-19-induced mobility restrictions? To address this, we decided to quantify people’s change of interest in foods when they spend more time at home and study how long these shifts in interests persist.

Mmmm… Yummy!

Foods and people’s interests

We used time-series capturing the popularity of Google search queries related to about 1.5k foods (e.g., pizza), and ways of accessing food (e.g., recipe) collected with Google Trends and calibrated with G-TAB library. Hence, the internal project name: Foodle Trends! 👀

Search queries can be specified as entity identifiers (e.g., “/m/021mn”) from the Freebase knowledge base. We use these identifiers to conduct a multilingual study of interest since they allow for grouping various surface forms relating to the same topic. For instance, the entity “Cookie” (“/m/021mn”) captures “cookies”, “cookie”, “Cookie”, or “cookie jar”, etc., while the entity “Recipe” (“/m/0p57p”) captures all recipe queries across languages.

Additionally, for each Freebase entity id, we queried Wikidata to get its “instance of” or “subclass of” properties. We then derived a taxonomy of 28 categories (e.g., pie, stew, cocktail) based on “subclass of” and “instance of” relations. A co-author who is a professional epidemiologist specializing in nutrition helped us assess and refine the entities and the categorization.

Such a multilingual and detailed analysis was possible by relying on Freebase and Wikidata knowledge—what a treat!

The modeling approach

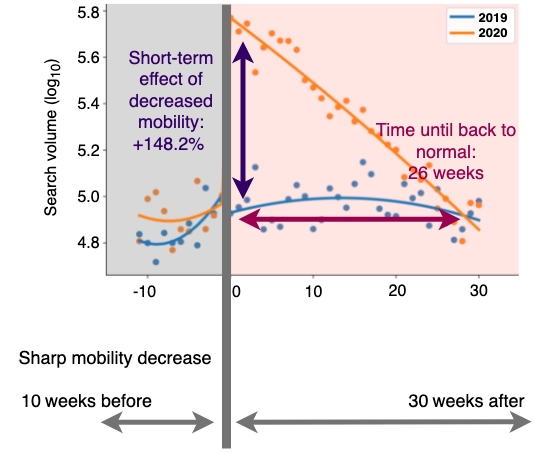

We then performed quasi-experimental time-series analyses that aim to isolate the effect of the discontinuity in mobility patterns on food interests, accounting for 2019 baseline trends (see how it works in the example of interest in pastry and bakery products in Brazil). Mobility patterns were captured via Google Mobility Reports.

The model lets us measure the short-term increase in interest (blue arrow) and the time it takes for the interest to revert to normal (red arrow). We also measure the long-term increase in interest: In case the interest did not go back to normal within the 30 weeks after the mobility decrease, we measure how elevated the interest remains at the end of the modeled period, 30 weeks after mobility decrease, compared to the interest in the same week in 2019.

Illustration of the modeling.

What did we find?

During the first wave of the pandemic, there was an immediate overall surge in food interest, larger and longer-lasting than the surge during typical end-of-year holidays in Western countries. The effects are comparable in amplitude and last longer. From a population health point of view, this is important and potentially concerning by analogy: Christmas and Thanksgiving are known to be disruptive to dietary habits and a hazard to balanced diets.

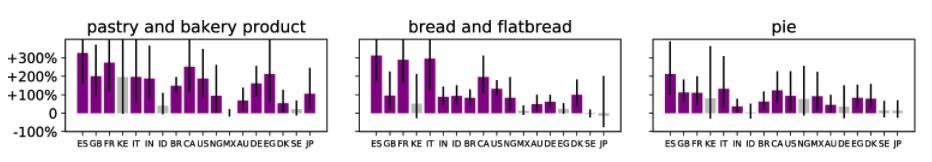

Next, we found that, in addition to the overall volume, the nature of the food interest also changed. The increased food interest is not uniform across types of food. The most prominent increases, in absolute and relative terms, occur for calorie-dense carbohydrate-based foods. These surges are not matched by proportional increases in interest in fresh produce. These results call for developing a deeper understanding of the exact mechanisms in how stress, boredom, and emotional eating are associated with the lockdown.

The short-term effects estimated with our RDD-based model, example food categories.

So what?

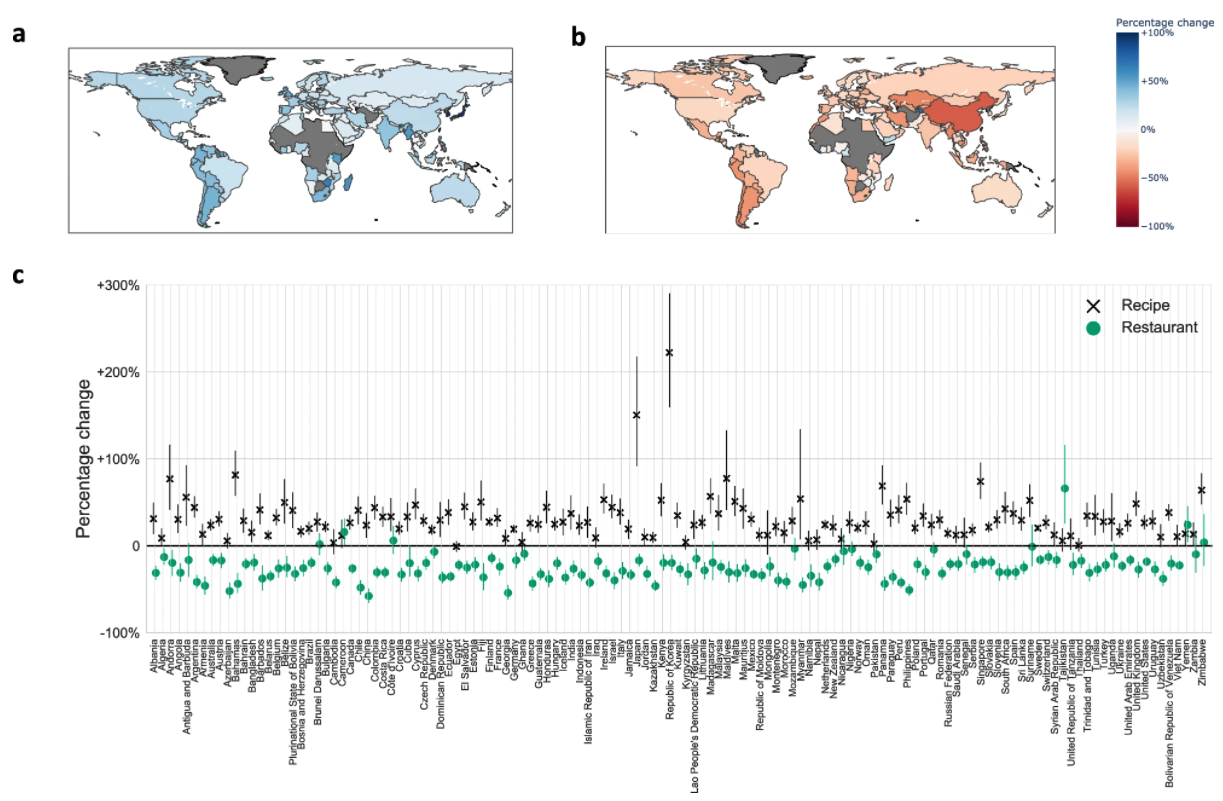

Our results indicate that, when confined, people are interested in carbohydrates and calorie-dense foods, likely due to changes in preferences on the one hand and due to changes in accessibility and price of foods on the other hand. These effects are consistent across countries, which is an indication that they occur across cultures and economic conditions, e.g., see globally across 129 countries with enough search data available to estimate weekly interest volumes.

In a search interest in the concept of “recipe” across countries, in 2020 vs. 2019. In b search interest in the concept of “restaurant” across countries, in 2020 vs. 2019. Countries with not enough search data are marked in gray. In c average relative change in interest in 52 weeks of 2020 in a country, compared to corresponding weeks of 2019.

Takeaway pizza message

These changes in dietary interests have the potential to globally reflect and affect food consumption and health. We hope these findings can inform governmental and organizational decisions regarding measures to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on diet. The goal was to point out prominent emerging behaviors, quantify the initial developments, and provide a broad grounding for future studies. We hope this is a good first step!

To read more, check out: