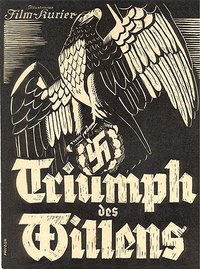

Triumph of the Will

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Films

| Triumph of the Will | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Leni Riefenstahl |

| Produced by | Leni Riefenstahl Adolf Hitler |

| Written by | Leni Riefenstahl Walter Ruttmann |

| Starring | Adolf Hitler Hermann Göring Other Nazi Leaders |

| Music by | Herbert Windt Richard Wagner |

| Distributed by | Reichsparteitagsfilm |

| Release date(s) | 28 March 1935 (Berlin) |

| Running time | 114 minutes |

| Language | German |

| Budget | Unknown |

| All Movie Guide profile | |

| IMDb profile | |

Triumph of the Will (German: Triumph des Willens) is a documentary and propaganda film by the German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl that chronicles the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg. It features footage of uniformed party members (though relatively few German soldiers), who are marching and drilling to classical melodies. The film contains excerpts from speeches given by various Nazi leaders at the Congress, including portions of speeches by Adolf Hitler. Hitler commissioned the film and served as an unofficial executive producer; his name appears in the opening credits. The overriding theme of the film is the return of Germany as a great power, with Hitler as a German Messiah who will bring glory to the nation.

Triumph of the Will was released in 1935 and rapidly became one of the best-known examples of propaganda in film history. Riefenstahl's techniques, such as moving cameras, the use of telephoto lenses to create a distorted perspective, aerial photography, and revolutionary approach to the use of music and cinematography, have earned Triumph recognition as one of the greatest propaganda films in history. Riefenstahl won several awards, not only in Germany but also in the United States, France, Sweden, and in other countries. The film was popular in the Third Reich and elsewhere, and has continued to influence movies, documentaries, and commercials to this day, even as it raises the question over the dividing line between art and morality.

Plot

Triumph of the Will has been described as "by Nazis, for Nazis, and about Nazis". The film begins with a prologue, the only commentary in the film. On a stone wall, the following text appears: On September 5, 1934, … 20 years after the outbreak of the World War … 16 years after the beginning of our suffering … 19 months after the beginning of the German renaissance … Adolf Hitler flew again to Nuremberg to review the columns of his faithful followers…

'Day 1': The film opens with shots of the clouds above the city, and then moves through the clouds to float above the assembling masses below, with the intention of portraying beauty and majesty of the scene. The shadow of Hitler's plane is visible as it passes over the tiny figures marching below, accompanied by music from Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, which slowly turns into the Horst-Wessel-Lied. Upon arriving at the Nürnberg airport, Hitler emerges from his plane to thunderous applause and a cheering crowd. He is then driven into Nürnberg, through equally enthusiastic people, to his hotel where a night rally is later held.

'Day 2': The second day begins with a montage of the attendees getting ready for the opening of the Reich Party Congress, and then footage of the top Nazi officials arriving at the Luitpold Arena. The film then cuts to the opening ceremony, where Rudolf Hess announces the start of the Congress. The camera then introduces much of the Nazi hierarchy and covers their opening speeches, including Joseph Goebbels, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Fritz Todt, Robert Ley, and Julius Streicher. Then the film cuts to an outdoor rally for the Reichsarbeitdienst (Labor Service), which is primarily a series of pseudo-military drills by men carrying shovels. This is also where Hitler gives his first speech on the merits of the Labor Service and praising them for their work in rebuilding Germany. The day then ends with a torchlight SA parade.

'Day 3': The third day starts with a Hitler Youth rally on the parade ground. Again the camera covers the Nazi dignitaries arriving and the introduction of Hitler by Baldur von Schirach. Hitler then addresses the Youth, describing in militaristic terms how they must harden themselves and prepare for sacrifice. Everyone present then assembles for a military pass and review, featuring Wehrmacht cavalry and various armored vehicles. That night Hitler delivers another speech to low-ranking party officials by torchlight, commemorating the first year since the Nazis took power and declaring that the party and state are one entity.

'Day 4': The fourth day is the climax of the film, where the most memorable of the imagery is presented. Hitler, flanked by Heinrich Himmler and Viktor Lutze, walks through a long wide expanse with over 150,000 SA and SS troops standing at attention, to lay a wreath at a World War I Memorial. Hitler then reviews the parading SA and SS men, following which Hitler and Lutze deliver a speech where they discuss the Night of the Long Knives purge of the SA several months prior. Lutze reaffirms the SA's loyalty to the regime, and Hitler absolves the SA of any crimes committed by Ernst Röhm. New party flags are consecrated by touching them to the " blood banner" (the same cloth flag carried by the fallen Nazis during the Beer Hall Putsch) and, following a final parade in front of the Nürnberg Frauenkirche, Hitler delivers his closing speech. In it he reaffirms the primacy of the Nazi Party in Germany, declaring, "All loyal Germans will become National Socialists. Only the best National Socialists are party comrades!" Hess then leads the assembled crowd in a final Sieg Heil salute for Hitler, marking the close of the party congress. The film fades to black as the entire crowd sings the " Horst-Wessel-Lied".

Origins

"Shortly after he came to power Hitler called me to see him and explained that he wanted a film about a Party Congress, and wanted me to make it. My first reaction was to say that I did not know anything about the way such a thing worked or the organization of the Party, so that I would obviously photograph all the wrong things and please nobody — even supposing that I could make a documentary, which I had never yet done. Hitler said that this was exactly why he wanted me to do it: because anyone who knew all about the relative importance of the various people and groups and so on might make a film that would be pedantically accurate, but this was not what he wanted. He wanted a film showing the Congress through a non-expert eye, selecting just what was most artistically satisfying — in terms of spectacle, I suppose you might say. He wanted a film which would move, appeal to, impress an audience which was not necessarily interested in politics." -- Leni Riefenstahl

Riefenstahl, a popular German actress, had directed her first movie called Das Blaue Licht (The Blue Light) in 1932. Around the same time she first heard Hitler speak at a Nazi rally and, by her own admission, was impressed. She later began a correspondence with him that would last for years. Hitler, by turn, was equally impressed with Das Blaue Licht, and in 1933 asked her to direct a film about the Nazi's annual rally in Nürenberg. The Nazis had only recently taken power amid a period of political instability (Hitler was the fourth Chancellor of Germany in less than a year) and were considered an unknown quantity by many Germans, to say nothing of the world.

Riefenstahl was initially reluctant, not because of any moral qualms, but because she wanted to continue making feature films. Hitler persisted and Riefenstahl eventually agreed to make a film at the 1933 Nürnberg Rally called Der Sieg des Glaubens. However the film had numerous technical problems, including a lack of preparation (Riefenstahl reported having just a few days) and Hitler's apparent unease at being filmed. To make matters worse, Riefenstahl had to deal with infighting by party officials, in particular Joseph Goebbels who tried to have the film released by the Propaganda Ministry. Though Sieg apparently did well at the box office, it later became a serious embarrassment to the Nazis after SA Leader Ernst Röhm, who had a prominent role in the film, was executed during the Night of the Long Knives.

In 1934, Riefenstahl had no wish to repeat the fiasco of Sieg and initially recommended fellow director Walter Ruttmann. Ruttmann's film, which would have covered the rise of the Nazi Party from 1923 to 1934 and been more overtly propagandistic (the opening text of Triumph was his), did not appeal to Hitler. He again asked Riefenstahl, who finally relented (there is still debate over how willing she was) after Hitler guaranteed his personal support and promised to keep other Nazi organizations, specifically the Propaganda Ministry, from meddling with her film.

Filmmaking

Unlike Der Sieg des Glaubens (German: victory of faith), Riefenstahl shot Triumph of the Will with a large budget, extensive preparations, and vital help from high-ranking Nazis like Goebbels. As Susan Sontag observed, "The Rally was planned not only as a spectacular mass meeting, but as a spectacular propaganda film." Albert Speer, Hitler's personal architect designed the set in Nürnberg and did most of the coordination for the event. Riefenstahl also used a film crew that was extravagant by the standards of the day. Her crew consisted of 172 people, including ten technical staff, thirty-six cameramen and assistants (operating in 16 teams with 30 cameras), nine aerial photographers, 17 newsreel men, 12 newsreel crew, 17 lighting men, two photographers, 26 drivers, 37 security personnel, four labor service workers, and two office assistants. Many of her cameramen also dressed in SA uniforms so they could blend into the crowds.

Triumph included innovative filmmaking techniques such as moving cameras, including one on an elevator attached to the mammoth flagpoles behind the speaker's podium, as well as another on Hitler's personal Mercedes (the latter requiring numerous takes so that the cameraman would not be filmed.) It also featured the use of telephoto lenses to create a distorted perspective. To capture other angles, Riefenstahl had pits dug below the speakers' podiums, tracks laid for moving shots, and aerial photography taken from several planes and a blimp. There were frequent close-ups of crowds watching and listening to Hitler, and poses of Hitler shot from well below eye-level to make him appear heroic. Aside from the prologue, Riefenstahl used no verbal editorial commentary in Triumph, preferring to make her points through rapid editing cuts, montages, and music. She also used "real sound" throughout the film. The film score was Wagnerian in scope (much of it was lifted directly from Wagner's operas), and tended to flow with Riefenstahl's edits, creating an atmosphere that was passionate and exuberant, frequently building up to a climactic frenzy whenever Hitler was about to speak.

The New York Times has said it took almost two years to edit the final version from 250 miles of raw footage. However, this time frame is obviously incorrect, as there were only 200 days between the rally in September 1934 and the premiere in March 1935. The New York Times is most likely referring to "Olympia," Riefenstahl's documentary about the 1936 Berlin Olympic games. In the documentary "The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl," the 400,000 meters (250 miles) of footage and the two years of editing are mentioned. In Triumph of the Will, however, Riefenstahl did have the difficult task of condensing an estimated 61 hours of film into two hours. She labored to complete the film as fast as she could, going so far as to sleep in the editing room filled with hundreds of thousands of feet of film footage.

Themes

"[Triumph of the Will is] the supreme visualisation in cinematic form of the Nazi political religion. Its artistry, reinforced by the grandeur and power of the Nürnberg decor, is designed to sweep us into empathetic identification with Hitler as a kind of human deity. The massive spectacle of regimentation, unity and loyalty to the Führer powerfully conveys the message that the Nazi movement was the living symbol of the reborn German nation." -- Professor Robert Wistrich

- Religion: This morning's opening meeting…was more than a gorgeous show, it also had something of the mysticism and religious fervor of an Easter or Christmas Mass in a great Gothic cathedral." -- Reporter William Shirer

Religion is a major theme in Triumph. The film opens with a Point Of View coming godlike out of the skies to alight on twin cathedral spires. It contains many scenes of church bells ringing, and individuals in a state of near-religious fervor, as well as a prominent shot of Reich Bishop Ludwig Müller standing in his vestments among high-ranking Nazis. A scene where the camera pans over rows and rows of tents set up for the rally is reminiscent of religious pilgrimages such as the Hajj. It is probably not a coincidence that the final parade of the film was held in front of the Nürnberg Frauenkirche. In his final speech in the film, Hitler also directly compares the Nazi party to a holy order, and the consecration of new party flags by having Hitler touch them to the "blood banner" has obvious religious overtones. Hitler himself is portrayed in a messianic manner, from the opening where he descends like Odin from the clouds, to his drive through Nürnberg where even a cat stops what it is doing to watch him, to the many scenes where — standing on his podium — he will issue a command to hundreds of thousands of followers and the audience will comply in unison. Frank Tomasulo comments that in Triumph, "Hitler is cast as a veritable German Messiah who will save the nation, if only the citizenry will put its destiny in his hands."

- Power: "It is our will that this state shall endure for a thousand years." -- Hitler

Germany had not seen images of military power and strength since the end of World War I, and the huge formations of men would remind the audience that Germany was becoming a great power once again. Though the men carried shovels, they handled them as if they were rifles. The Eagles and Swastikas could be seen as a reference to the Roman Legions of antiquity. The large mass of well-drilled party members could be seen in a more ominous light, as a warning to anyone thinking of challenging the regime. Hitler's arrival in an airplane should also be viewed in this context. According to Kenneth Poferl, "Flying in an airplane was a luxury known only to a select few in the 1930s, but Hitler had made himself widely associated with the practice, having been the first politician to campaign via air travel. Victory reinforced this image and defined him as the top man in the movement, by showing him as the only one to arrive in a plane and receive an individual welcome from the crowd. "Hitler's speech to the SA also contained an implied threat: if he could have Röhm -- the commander of the hundreds of thousands of troops on the screen -- shot, it was only logical to assume that Hitler could get away with having anyone executed.

- Unity: "The Party is Hitler - and Hitler is Germany just as Germany is Hitler!" -- Hess

Triumph has many scenes that blur the distinction between the Nazi Party, the German State, and the German People. There are scenes where Germans in peasant farmers’ costumes and other traditional clothing greet Hitler. The torchlight processions, though now associated by many with the Nazis, would remind the viewer of the medieval Karneval celebration. The old flag of Imperial Germany is also shown several times flying alongside the Swastika, and there is a ceremony where Hitler pays his respects to soldiers who died in World War I (as well as President Paul von Hindenburg who had died a month before the convention). There is also a scene where the Labor Servicemen individually call out which town or area in Germany they are from, reminding the viewers that the Nazi Party had expanded from its stronghold in Bavaria to become a pan-Germanic movement.

Response

Triumph of the Will premiered on March 28, 1935 at the Berlin Ufa Palace Theatre and was an instant success. Within two months the film had earned 815,000 Reichsmark, and the Ufa considered it one of the three most profitable films of that year. Hitler praised the film as being an "incomparable glorification of the power and beauty of our Movement." For her efforts, Riefenstahl was rewarded with the German Film Prize (Deutscher Filmpreis), a gold medal at the 1935 Venice Biennale, and the Grand Prix at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris. However, there were few claims that the film would result in a mass influx of ' converts' to fascism and the Nazis apparently did not make a serious effort to promote the film outside of Germany. Film historian Richard Taylor also said that Triumph was not generally used for propaganda purposes inside the Third Reich, although Roy Frumkes argued that, on the contrary, it was shown each year in every German theatre until 1945.

The reception in other countries was not as enthusiastic. British documentarian Paul Rotha called it tedious, while others were repelled by its pro-Nazi sentiments. During World War II, Frank Capra made a direct response called Why We Fight, a series of newsreels commissioned by the United States government that spliced in footage from Triumph of the Will, but recontextualized it so that it promoted the cause of the Allies instead. Capra later remarked that Triumph, "fired no gun, dropped no bombs. But as a psychological weapon aimed at destroying the will to resist, it was just as lethal." Clips from Triumph were also used in an Allied propaganda short called General Adolph Takes Over, set to the British dance tune " The Lambeth Walk." The legions of marching soldiers, as well as Hitler giving his Nazi salute, were made to look like wind-up dolls, dancing to the music. Also during WWII, the poet Dylan Thomas wrote the screenplay and narrated "These Are The Men," a propaganda piece using "Triumph" footage to discredit Nazi leadership.

One of the best ways to gauge the response to Triumph was the instant and lasting international fame it gave Riefenstahl. The Economist said it "sealed her reputation as the greatest female filmmaker of the 20th century." For a director who made eight films, only two of which received significant coverage outside of Germany, Riefenstahl had unusually high name recognition for the remainder of her life, most of it stemming from Triumph. However, her career was also permanently damaged by this association. After the war, Riefenstahl was imprisoned by the Allies for four years for allegedly being a Nazi sympathizer and was permanently blacklisted by the film industry. When she died in 2003, 68 years after its premiere, her obituary received significant coverage in many major publications -- including the Associated Press, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and The Guardian -- most of which reaffirmed the importance of Triumph.

Controversy

Like American filmmaker D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, Triumph of the Will has been criticized as a use of spectacular filmmaking to promote a system that, to many in modern times, is seen as both evil and unjust. In Germany, this movie is classified as National Socialist propaganda and its showing is restricted under post-war denazification laws, but it may be shown in an educational context. In her defense, Riefenstahl claimed that she was naïve about the Nazis when she made it and had no knowledge of Hitler's genocidal policies. She also pointed out that Triumph contains "not one single anti-Semitic word," although it does contain a veiled comment by Julius Streicher that "A people that does not protect its racial purity will perish." However, Roger Ebert has observed that for some, "the very absence of anti-Semitism in Triumph of the Will looks like a calculation; excluding the central motif of almost all of Hitler's public speeches must have been a deliberate decision to make the film more efficient as propaganda."

Riefenstahl also repeatedly defended herself against the charge that she was a Nazi propagandist, saying that Triumph focuses on images over ideas, and should therefore be viewed as a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). In 1964, she returned to this topic, saying:

- "If you see this film again today you ascertain that it doesn't contain a single reconstructed scene. Everything in it is true. And it contains no tendentious commentary at all. It is history. A pure historical film… it is film-vérité. It reflects the truth that was then in 1934, history. It is therefore a documentary. Not a propaganda film. Oh! I know very well what propaganda is. That consists of recreating events in order to illustrate a thesis, or, in the face of certain events, to let one thing go in order to accentuate another. I found myself, me, at the heart of an event which was the reality of a certain time and a certain place. My film is composed of what stemmed from that."

However, Riefenstahl was an active participant in the rally, though in later years she downplayed her influence significantly, claiming, "I just observed and tried to film it well. The idea that I helped to plan it is downright absurd." Film critic Roy Frumkes has called Triumph "the antithesis of an objective work" and suggested that because of the special accommodations Riefenstahl received (one scene featured aerial searchlights requisitioned from the Luftwaffe) and because "the film was altered by practically every in-the-camera and laboratory special effect then known" the film can be labeled anything except a documentary. Ebert also disagrees, saying that Triumph is "by general consent [one] of the best documentaries ever made," but added that because it reflects the ideology of a movement regarded by many as evil, "[it poses] a classic question of the contest between art and morality: Is there such a thing as pure art, or does all art make a political statement?"

Susan Sontag considered Triumph of the Will the best made documentary of all time. Brian Winston's essay on the film in The Movies as History : Visions of the Twentieth Century, an anthology edited by David Ellwood (published by the International Association for Media and History), is largely a critique of Sontag's analysis, which he finds faulty. His ultimate point is that any filmmaker could have made the film look impressive because the Nazi's mise en scène was impressive, particularly when they were offering it for camera re-stagings. In form, the film alternates repetitively between marches and speeches. Winston asks the viewers to consider if such a film should be seen as anything more than a pedestrian effort. Like Rotha, he finds the film tedious, and believes anyone who takes the time to analyze its structure will quickly agree.

Wehrmacht objections

The first controversy over Triumph occurred even before its release, when several generals in the Wehrmacht protested over the minimal army presence in the film. Only one scene, the review of the German cavalry, actually involved the German military. The other formations were party organizations that were not part of the military. Hitler proposed his own "artistic" compromise where Triumph would open with a camera slowly tracking down a row of all the "overlooked" generals (and placate each general's ego). According to her own testimony, Riefenstahl refused his suggestion and insisted on keeping artistic control over Triumph of the Will. She did agree to return to the 1935 rally and make a film exclusively about the Wehrmacht, which became Tag der Freiheit.

Influences and legacy

According to historian Philip Gavin, "The legacy of Triumph of the Will lives on today in the numerous TV documentaries concerning the Nazi era which replay portions of the film… [Its] most enduring and dangerous illusion is that Nazi Germany was a super-organized state, that, although evil in nature, was impressive nonetheless." Gavin believes that the reality of Nazism as a disorganized and bureaucratic mess was obscured by Triumph of the Will's powerful images of a united Fascist movement. Nicholas Reeves concurs, adding that "many of the most enduring images of the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler derive from Riefenstahl’s film."

Triumph of the Will has also been studied by many contemporary artists (at his wedding, Mick Jagger told Riefenstahl that he had seen it at least fifteen times), including film directors Peter Jackson, George Lucas, and Ridley Scott. The first known movie to use Triumph imagery is Charlie Chaplin's The Great Dictator, which ironically was a parody of Nazism. Scenes from the film have also been imitated in later movies, most famously Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (as well as the other Star Wars films). Other films to use either Triumph–like imagery or scenes from the film are Citizen Kane, A Clockwork Orange, Gladiator, Hero, Lord of the Rings, The Lion King, Richard III, Red Dawn, Spartacus, The Wall, and Starship Troopers. The movie The Empty Mirror even shows several scenes from Triumph, with Hitler (played by Norman Rodway) giving his analysis of them. Some see the musical Springtime for Hitler in the Mel Brooks comedy The Producers as a spoof of Triumph, though Brooks has denied this.

The film's fame (or infamy) has even turned the phrase "Triumph of the Will" into a gag line, because so many people understand the reference. For example, in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, when Dr. Frank N. Furter shows his creation to his retainers, his maid exclaims in a strong German accent that it is "a triumph of your vill." In addition, the Boomtown Rats song "(I Never Loved) Eva Braun" also includes the line "Eva Braun…never really fitted in the scheme of things/She was a triumph of my will." The title was also referenced in the Dead Kennedys song "Triumph of the Swill" as well as the 1979 Devo song "Triumph of the Will." In the DVD of " Venue Songs" from They Might Be Giants, the Anaheim House of Blues was described as having a "Triumph-of-the-Will management style."

The film has also influenced American politics. The director of a political ad for Nelson Rockefeller's 1968 presidential campaign admitted he used Triumph as a reference. Some American political commentators have also compared both the Republican and Democratic Party Conventions to Triumph of the Will, although these criticisms are usually partisan in nature.