Scanian (linguistics)

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Linguistics

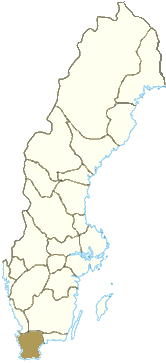

Scanian ( skånska ) is a closely related group of dialects spoken in the Southern-Swedish region Skåne (Scania). It is considered by some Scandinavian linguists to be a dialect of Swedish, by other Scandinavian linguists to be a dialect of Danish, while many early linguists, including Adolf Noreenand G. Sjöstedt, classified it as "South-Scandinavian". It is however classified as a separate language by SIL International ( ISO 639-3:scy) and is assumed to include not only the dialect of Skåne but also those of Halland (halländska), Blekinge (blekingska), and the Danish island of Bornholm (bornholmsk).

Status

Scanian is considered a separate language mainly from a historical, cultural or ethnic point of view. It is not regarded as a separate language by a majority of Swedes, but with the establishment of the Scanian Academy and with recent heritage conservation programs funded by the Swedish Government, there is a renewed interest in the region for Scanian as a cultural language and as a regional identity, especially among younger generations of Scanians. Many of the genuine rural dialects have been in decline subsequent to the industrial revolution and urbanization in Sweden. However, Scanian regionalist debaters express the view that Scanian is a suppressed minority language, and that it therefore should be considered an official minority language.

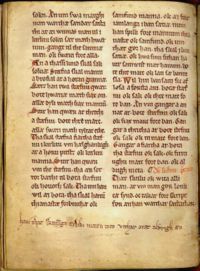

It is classified as a separate language by SIL International ( ISO 639-3:scy) and is assumed to include not only the dialect of Skåne but also those of Halland (halländska), Blekinge (blekingska), and the Danish island of Bornholm (bornholmsk). This larger definition coincides with the extent of Skåneland (Terra Scaniae), a medieval term which has regionalist overtones but also historical substance. The medieval Skånske Lov (Codex Runicus) applied to all four provinces and in the Landsting (Thing), the governing assembly, the four provinces chose and paid homage to the king as a unity. According to SIL International there were 80.000 people who spoke the Scanian language in Sweden in 2002, with Scania, Halland and Blekinge having a combined population of about 1,6 million people.

The population of Skåne consists of around 13% of the total population in Sweden. Scanian is one of the most distinctive dialects in Sweden. In an internet poll on the website of a major newspaper in which more than 30,000 people have voted, Scanian is currently ranked in second place (12,5%) for most beautiful dialect, but also considered the dialect most people consider ugly (39,4%).

History

After the Swedish acquisition of the Danish districts Skåne, Blekinge, and Halland (collectively known as Skåneland) with the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658, a process of Swedification was introduced, including a switch of languages used in churches and restrictions imposed on cross border travel and trade. A similar change occurred within other newly acquired provinces along the west coast and along the border with Norway. Bornholm was once part of Skåneland, but it was lost by Sweden in 1659. Scanian remained in use in Bornholm as a functioning transitional stage before Standard Danish became dominant in official contexts. In Scania, the Swedish government officially limited the use of Scanian in 1719 by nullifying the self-rule granted in The Treaty of Roskilde, where Scania had initially been granted the right to continue with the old privileges, laws and customs. The assimilation has accelerated during the 20th century with the dominance of Standard Swedish language radio and television, urbanization, and movement of people to and from the other regions of Sweden.

Historic shifts

The gradual transition to Swedish has resulted in a local creolisation, with many new Swedish characteristics introduced since the 18th century. The result of this slow shift is a distinct Scanian form of pronunciation, with details of grammar and vocabulary that in some aspects differ from Standard Swedish. The degree of contrast between Scanian and Swedish could be considered comparable to the differences between American and Australian English. As pointed out by the researchers involved in the project Comparative Semantics for Nordic Languages, it is difficult to quantify and analyze the fine degrees of semantic differences that exist, even between Danish, Swedish and Norwegian: "[S]ome of the Nordic languages [..]are historically, lexically and structurally very similar.[...]Are there systematic semantic differences between these languages? If so, are the formal semantic analytic tools that have been developed mainly for English and German sufficiently fine-grained to account for the differences among the Scandinavian languages?"

The characteristic Scanian diphthongs, which do not occur in Danish or Swedish, are in popular belief often seen as signs of Scanian natives' efforts to adapt from a Danish to a "proper" Swedish pronunciation. However, linguists reject this explanation for the sound change; at present, there are no universally-accepted theories for why sound changes occur. Danish research supports the assertion that Scanian was a distinct dialect before the Swedish acquisition of most of old Skåneland. One of the artifacts supporting this is a letter from the 16th century, where the Danish Bible translators were advised not to employ Scanian translators since their language was not proper Danish.

Historic preservation

Scanian once possessed many unique words which do not exist in neither Swedish nor Danish. In attempts to preserve the unique aspects of Scanian, these words have been recorded and documented by the Institute for Dialectology, Onomastics and Folklore Research. Preservation is also accomplished through comparative studies, such as the Scanian-Swedish-Danish dictionary project, commissioned by the Scanian Academy. This project is led by Dr. Helmer Lång and involves a group of scholars from different fields, including Professor Birger Bergh, linguistics, Professor Inger Elkjær and Dr. Inge Lise Pedersen, researcher in Danish dialects. Many specialty Scanian dictionaries have been published through the years, including one by Dr. Sten Bertil Vide, who wrote his doctoral thesis on the names of flowers in Scanian. This publication, and a variety of other Scanian dictionaries are available through Department of Dialectology and Onomastics in Lund.

The words and pronunciation differ around Scania, as they were sometimes only spoken by a small number of people in remote villages. Villages close to the sea, for example, such as Falsterbo and Limhamn, had many unique words connected to fishing. Most of these words no longer have any use in the spoken language.

Modern history

General public and academic interest in protecting the Scanian dialect or language was first established in the early 19th century with the advent of folkloristics and romantic nationalism in Scandinavia (see for example Norwegian romantic nationalism). According to Helmer Lång, Scanian and the folklore of the region had not been given proper attention because the Swedes considered them Danish, and the Danes, on the other hand, avoided dealing with this area which they had lost.

An early advocate was Henrik Wranér (1853-1908) who wrote books on Scanian (Kivikja Snackk..., 1901). His contribution was manifested with his Selected Works (Valda Verk) which was published in 1922-23. His primary successor was Axel Ebbe (1869-1941), who wrote Rijm å rodevelske in Scanian along with a witty translation of the Bible (Bibelsk historie, 1949).

Scanian was not well known north of Skåneland and its adjacent districts until the Scanian movie actor Edvard Persson sang his way into the hearts of the Swedish nation during the 1930s and 1940s. More recently, radio voices Kjell Stensson and Sten Broman have popularized the dialect.

Today

There are a sizable number of singers and other celebrities who speak Scanian and use it in their professional life. Artist Mikael Wiehe, voted "Scanian of the Year" in 2000, explained his relation to Scanian by referring a "love, knowledge of and pride in Scania's history and uniqueness": "To be a Scanian, to love Scania, to take an interest in its history and to cherish its uniqueness [...] has helped me to understand and respect other people's love for and pride over their native area. [...] In the same way, I love the Scanian language. Not because it is better than other languages, but because it is the language I express myself best in. This love for my native region and my language has given me a security and confidence which has made it possible for me to go out and explore the world without fear." Wiehe received the Swedish Martin Luther King Award of 2005 for his work at home and internationally for peace, freedom, justice and solidarity. Hans Alfredson, a popular showman, producer, singer and performer during the last 50 years, has produced several movies with Scanian dialogue, including the internationally recognized movie "The Simple-Minded Murder", starring Scanian-speaking Stellan Skarsgård who grew up in Malmö. Thomas Öberg, the singer of Swedish rock group bob hund, is a notable speaker of Scanian, who also sings in Scanian. The rock band Kal P. Dal, considered a cult favourite in some areas, Björn Afzelius, rock artist Peps Persson and the band Joddla med Siv are also popular examples of Scanian artists. The folk-singer Danne Stråhed is very popular in some regions, not the least due to his trademark song När en flicka talar skånska ("When a girl speaks Scanian").

Recently, several humorously written Scanian dictionaries have been published. As there is no Scanian language standard, the choice of words to be included is always under debate.

Sounds

Scanian realizes the phoneme /r/ as a uvular trill, [ʀ] in clear articulation, but in everyday speech more commonly as a voiceless, [χ] or voiced uvular fricative, [ʁ], depending on phonetic context. This is in contrast to the alveolar articulations and retroflex assimilations in most Swedish dialects north of Småland. The realizations of the highly variable and uniquely Swedish fricative /ɧ/ also tend to be more velar and less labialized than in other dialects. Though the phonemes of Scanian correspond to those of Standard Swedish and most other Swedish dialects, long vowels have developed into diphthongs which are unique to the region. In the southern parts of Skåne many diphthongs also have a pharyngeal quality, similar to Danish vowels.

Vocabulary

While the general vocabulary does not differ considerably from Standard Swedish, a few specifically Scanian words exist which are known in all of Scania, occurring frequently among a majority of the speakers. These are some examples:

- påg , "boy" (Standard Swedish: pojke, former Danish: poge / pog)

- tös, "girl" (Standard Swedish: flicka, Danish: tøs)

- rälig, "disgusting", "ugly" (Standard Swedish äcklig, ful, dialect Danish: rærlig)

There are other Scanian words that are well-known in Scania but could be considered old-fashioned or extremely rural in general usage:

- pantoffel, "potatoe" (Standard Swedish: potatis, Danish: kartoffel)