Australian English

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Languages

Australian English (AuE) is the form of the English language used in Australia.

History

Australian English began to diverge from British English soon after the foundation of the Colony of New South Wales in 1788. The settlement was intended mainly as a penal colony. The British convicts sent to Australia were mostly people from large English cities, such as Cockneys from London. In addition to these many of the original immigrants were free settlers, military personnel and administrators and their families. In 1827, Peter Cunningham, in his book Two Years in New South Wales, reported that native-born white Australians spoke with a distinctive accent and vocabulary, albeit with a strong Cockney influence. (The transportation of convicts to Australian colonies continued until 1868, but immigration of free settlers from Britain continued unabated.) A much larger wave of immigration, as a result of the first Australian gold rushes, in the 1850s, also had a significant influence on Australian English, including large numbers of people who spoke English as a second language.

The " Americanisation" of Australian English — signified by the borrowing of words, spellings, terms, and usages from North American English — began during the goldrushes, and was accelerated by a massive influx of United States military personnel during World War II. The large-scale importation of television programs and other mass media content from the US, from the 1950s onwards, including more recently US computer software, especially Microsoft's spellchecker, has also had a significant effect. As a result Australians use many British and American words interchangeably, such as pants/trousers or lift/elevator, while shunning other words such as "wildfire" as too American when a more Australian term "bushfire" is preferred.

Due to their shared history and geographical proximity, Australian English is most similar to New Zealand English. However, the difference between the two spoken versions is obvious to people from either country, if not to a casual observer from a third country. The vocabulary used also exhibits some striking differences.

Irish influences

There is some influence from Hiberno-English, but perhaps not as much as might be expected given that many Australians are of Irish descent. One such influence is the pronunciation of the name of the letter "H" as "haitch" /hæɪtʃ/, which can sometimes be heard amongst speakers of "Broad Australian English", rather than the unaspirated "aitch" /æɪtʃ/ more likely to be heard in South Australia and common in New Zealand, most of Britain and North America. This is thought to be the influence of Irish Catholic priests and nuns.

Other Irish influences include the non-standard plural of "you" as "youse" /jʉːz/, sometimes used informally in Australia, and the expression "good on you" or "good onya". Of these the former is common throughout North America and the latter is encountered in New Zealand English and British English. Another Irish influence is use of the word 'me' replacing 'my', such as in the phrase Where's me hat? This usage is generally restricted to informal situations. Another influence is the use of the term "after" as it is used in hiberno English.

Phonology

Australian English is a non-rhotic dialect. The Australian accent is most similar to that of New Zealand and is also similar to accents from the South-East of Britain, particularly those of Cockney and Received Pronunciation. As with most dialects of English, it is distinguished primarily by its vowel phonology.

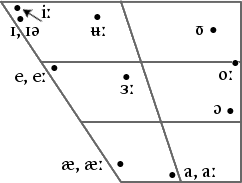

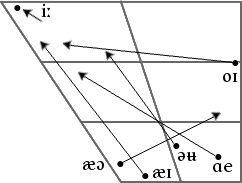

Australian English vowels are divided into two categories: long, which includes long monophthongs and diphthongs, and short, all of which are monophthongs. The short vowels mostly correspond to the lax vowels used in analyses of Received Pronunciation with the long vowels corresponding to its tense vowels as well as its centralising diphthongs. Unlike most varieties of English, it has a phonemic length distinction: a number of vowels differ only by the length.

Australian English consonants are similar to those of other non-rhotic varieties of English. In comparison to other varieties, it has a flapped variant of /t/ and /d/ in similar environments as in American English. Many speakers have also coalesced /tj/ and /dj/ into /tʃ/ and /dʒ/, with pronunciations such as /tʃʉːn/ being standard.

Vocabulary

Australian English incorporates many terms that Australians consider to be unique to their country. One of the best-known of these is outback which means a remote, sparsely-populated area. The similar bush can mean either native forests, or country areas in general. However, both terms are historically widely used in many English-speaking countries. Many such words, phrases or usages originated with the British convicts transported to Australia. Many words used frequently by country Australians are, or were, also used in all or part of England, with variations in meaning. For example: a creek in Australia, as in North America, is any stream or small river, whereas in England it is a small watercourse flowing into the sea; paddock is the Australian word for a field, while in England it is a small enclosure for livestock and; wooded areas in Australia are known as bush or scrub, as in North America, while in England, they are commonly used only in proper names (such as Shepherd's Bush and Wormwood Scrubs). Australian English and several British English dialects (eg. Cockney; Geordie) also both use the word mate to mean a close friend of the same gender and increasingly with platonic friend of the opposite sex (rather than the conventional meaning of "a spouse"), although this usage has also become common in some other varieties of English.

The origins of other terms are not as clear, or are disputed. Dinkum (or "fair dinkum") means "true", or when used in speech: "is that true?", "this is the truth!", and other meanings, depending on context and inflection. It is often claimed that dinkum dates back to the Australian goldrushes of the 1850s, and that it is derived from the Cantonese (or Hokkien) ding kam, meaning "top gold". However, scholars give greater credence to the notion that it originated with a now-extinct dialect word from the East Midlands in England, where dinkum (or dincum) meant "hard work" or "fair work", which was also the original meaning in Australian English. The derivation dinky-di means a 'true' or devoted Australian. The words dinkum or dinky-di and phrases like true blue are widely purported to be typical Australian sayings, but the majority of Australians, these days, don't say these at all, except when parodying the stereotypically "Australian" way of speaking.

Similarly, g'day, a stereotypical Australian greeting, is no longer synonymous with "good day" in other varieties of English (it can be used at night time) and is never used as an expression for "farewell", as "good day" is in other countries.

Some elements of Aboriginal languages have been incorporated into Australian English, mainly as names for places, flora and fauna (for example dingo, kangaroo). Beyond that, few terms have been adopted into the wider language, except for some localised terms, or slang. Some examples are cooee and Hard yakka. The former is a high-pitched call (pronounced /kʉː.iː/) which travels long distances and is used to attract attention. Cooee has also become a notional distance: if he's within cooee, we'll spot him. Hard yakka means hard work and is derived from yakka, from the Yagara/ Jagara language once spoken in the Brisbane region. Also from the Brisbane region comes the word bung meaning broken. A failed piece of equipment might be described as having bunged up or referred to as "on the bung" or "gone bung". Bung is also used to describe an individual who is pretending to be hurt; such individual is said to be "bunging it on".

Though often thought of as an Aboriginal word, didgeridoo (a well known wooden musical instrument) is probably an onomatopaoeic word of Western invention. It has also been suggested that it may have an Irish derivation.

Spelling

Australian spelling is generally very similar to British spelling, with a few exceptions (for example, program is more common than programme). Publishers, schools, universities and governments typically use the Macquarie Dictionary as a standard spelling reference. Both -ise and -ize are accepted, as in British English, but -ise is the preferred form in Australian English by a ratio of about 3:1 according to the Macquarie's Australian Corpus of English.

There is a widely held belief in Australia that "American spellings" are a modern intrusion, but the debate over spelling is much older and has little to do with the influence of North American English. For example, a pamphlet entitled The So-Called "American Spelling.", published in Sydney some time before 1900, argued that "there is no valid etymological reason for the preservation of the u in such words as honour, labor, etc." The pamphlet noted, correctly, that "the tendency of people in Australasia is to excise the u, and one of the Sydney morning papers habitually does this, while the other generally follows the older form".

Many Australian newspapers once excised the "u", for words like "colour" but do not anymore, and the Australian Labor Party retains the "-or" ending it officially adopted in 1912. Because of a backlash to the perceived " Americanisation" of Australian English, there is now a trend to reinsert the "u" in words such as harbour. The town of Victor Harbour now has the Victor Harbour Railway Station and the municipality's official website speculates that excising the 'u' from the town's name was originally a 'spelling error'. This continues to cause confusion in how the town is named in official and unofficial documents

The official (although not commonly used) spelling of gaol/jail is gaol although most Australians would write jail naturally.

In academia, as long as the spelling is consistent, the usage of various English variants is generally accepted.

Varieties of Australian English

Most linguists consider there to be three main varieties of Australian English. These are Broad, General and Cultivated Australian English. These three main varieties are actually part of a continuum and are based on variations in accent. They often, but not always, reflect the social class and/or educational background of the speaker.

Broad Australian English is the archetypal and most recognisable variety. It is familiar to English speakers around the world because of its use in identifying Australian characters in non-Australian films and television programs. Examples include television personalities Steve Irwin and Dame Edna Everage.

General Australian English is the stereotypical variety of Australian English. It is the variety of English used by the majority of Australians and it dominates the accents found in contemporary Australian-made films and television programs. Examples include actors Russell Crowe and Nicole Kidman. Cultivated Australian English has many similarities to British Received Pronunciation, and is often mistaken for it. Cultivated Australian English is now spoken by less than 10% of the population. Examples include actors Judy Davis and Geoffrey Rush.

It is sometimes claimed that there are regional variations in pronunciation and accent. If present at all, however, they are very small compared to those of British and American English – so much so that linguists are divided on the question. Overall, pronunciation is determined less by region than by social, cultural and educational influences, as well as by a general difference between urban and rural voices that can be heard throughout Australia.

One example of a minor difference in pronunciation exists in the pronunciation of words such as: castle, dance, chance, advance, etc. In Queensland and Victoria, the Irish pronunciation of these words, choosing the æ-vowel, is preferred, whereas in New South Wales, the a:-vowel, found in English English, is preferred. The NSW pronunciation of these words is somewhat more predominant in such examples as in singing the national anthem, Advance Australia Fair, where [əd'va:ns] remains the preferred pronunciation of "advance" where it might otherwise be pronounced [əd'væ:ns] in Queensland and Victoria.

There is, however, some variation in Australian English vocabulary between different regions. Of particular interest in this respect are sporting terms and terms for food, clothing and beer glasses.

Use of words by Australians

Many Australians believe themselves to be direct in manner and/or admire frank and open communication. Such sentiments can lead to misunderstandings and offence being caused to people from other cultures.

For instance, spoken Australian English is generally more tolerant of offensive and/or abusive language than other variants. A famous exponent was the former Prime Minister Paul Keating, who referred in Parliament to various political opponents as a "mangy maggot", a "stupid foul-mouthed grub", and so on.

An important aspect of Australian English usage, inherited in large part from Britain and Ireland, is the use of deadpan humour, in which a person will make extravagant, outrageous and/or ridiculous statements in a neutral tone, and without explicitly indicating they are joking. Tourists seen to be gullible and/or lacking a sense of humour may be subjected to tales of kangaroos hopping across the Sydney Harbour Bridge, " drop bears" and similar tall tales.

Australian English makes frequent use of diminutives. They can be formed in a number of ways and can be used to indicate familiarity. Some examples include arvo (afternoon), servo ( service station), bottle-o ( bottle-shop), barbie (barbecue), cozzie (swimming costume), footy (Australian rules football or rugby) and mozzie (mosquito). Occasionally, a -za diminutive is used, usually for personal names where the first of multiple syllables ends in an "r" for example Bazza (Barry) and Shazza (Sharon).

Many phrases once common to Australian English have become the subject of common stereotypes, over-use and Hollywood's caricaturised overexaggerations, even though they have largely disappeared from everyday use. Words being used less often include cobber, strewth, you beaut and crikey, and archetypal phrases like Flat out like a lizard drinking are rarely heard without a sense of irony.

The phrase Put a shrimp on the barbie is a misquotation of a phrase that became famous after being used by Paul Hogan in tourism advertisements that aired in America. Most Australians use the term prawn rather than shrimp, and do not commonly barbeque them. Many people trying to impersonate or mock an Australian will use this line, though Australians themselves would never have used this line.

Australia's unofficial national anthem Waltzing Matilda written by bush poet Banjo Patterson, contains many obsolete Australian words and phrases that appeal to a rural ideal and are understood by Australians even though they are not in common usage outside this song. One example is the title, which means travelling (particularly with a type of bed roll called a swag). Thus the refrain "You'll come a waltzing matilda with me" means you will come travelling with me. Part of the appeal of the song as distinctively Australian is its incomprehension to non-native Australian English speakers.