Palmyra Atoll

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Geography of Oceania (Australasia)

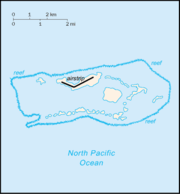

Palmyra Atoll, is an incorporated atoll administered by the United States government. The atoll is 4.6 square miles (12 km²) and it is located in the Northern Pacific Ocean at . Geographically, Palmyra is one of the Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati Line Islands), located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly halfway between Hawaii and American Samoa. Its 9 miles (14.5 km) of coastline has one anchorage known as West Lagoon. It consists of an extensive reef, two shallow lagoons, and some 50 sand and reef-rock islets and bars covered with vegetation—mostly coconut trees, Scaevola, and tall Pisonia trees.

The islets of the atoll are all connected, except Sand Island in the West and Barren Island in the East. The largest island is Cooper Island in the North, followed by Kaula Island in the South. The northern arch of islets is formed by Strawn Island, Cooper Island, Aviation Island, Quail Island, Whippoorwill Island, followed in the East by Eastern Island, Papala Island, and Pelican Island, and in the South by Bird Island, Holei Island, Engineer island, Marine Island, Kaula Island, Paradise Island and Home Island (clockwise). Average annual rainfall is approximately 175 inches (4,445 mm) per year. Daytime temperatures average 85° F year round.

Political status

Palmyra is an incorporated territory of the United States, meaning that it is subject to all provisions contained in the United States Constitution and is permanently under U.S. sovereignty. However, it is also an unorganized territory as there is no Congressional act specifying how it should be governed; the only relevant law simply gives the President the discretion to administer the island as he sees fit (see Section 48 of the Hawaii Omnibus Act, Pub. L. 86–624, July 12, 1960, 74 Stat. 411, attached as a note to former sections 491 to 636 of Title 48, United States Code ).

The atoll is part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands. The issue of Palmyra's governance is an obviously moot point, as there is no indigenous population remaining nor any reason to think that there will be one in the future. It remains therefore currently the only unorganized incorporated U.S. territory. It is privately owned by The Nature Conservancy and managed as a nature reserve, but administered from Washington, D.C. by the Office of Insular Affairs, United States Department of the Interior. The surrounding waters, out to the 12 mile (22.2 km) limit, were transferred to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and designated as the Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge in 2001. Defense is the responsibility of the United States.

There is no current economic activity on the island. Many of the roads and causeways on the atoll were built during World War II. All are now unserviceable and overgrown. There is a roughly 2,200 yard (2,000 m) long, unpaved and unimproved airstrip. Various abandoned World War II-era structures are found on the island.

The atoll has been manned by a group of scientists and volunteers (totalling between four and 20 in all) for the last several years. A series of improvements in 2004 consisted of new two-person bungalows and showers for the island's inhabitants. Water is collected from the roof of a concrete building not far from the main living area of the scientists. Communal buildings of the settlement on the north side of Cooper Island (the only one on the atoll) consist of a common cooking/dining building adjacent to the Atoll's only dock and a kayak and scuba equipment storage building next to the launch ramp.

Palmyra Atoll's location in the Pacific Ocean, where the southern and northern currents meet, means that its beaches are littered with trash and debris. Plastic mooring buoys are particularly plentiful on the beaches of Palmyra, as well as plastic bottles for soft drinks, detergents, etc.

Large parts of the Atoll are closed to any sort of public access due to the threat of uncleared World War II ordnance.

History

Palmyra was first sighted in 1798 by an American sea captain, Edmund Fanning of Stonington, Connecticut, while his ship the Betsy was in transit to Asia, but it was only later—on November 7, 1802—that the first western people landed on the uninhabited atoll. On that date, Captain Sawle of the U.S. ship Palmyra was wrecked on the atoll.

In 1859, Palmyra was claimed by Dr. Gerrit P. Judd of the brig Josephine for the American Guano Company and the United States, in accordance with the Guano Islands Act of 1856; however, the company never started mining for guano, because there was none to be mined. Palmyra is located close to the Intertropical Convergence Zone; there is too much rain for guano to accumulate. In the meanwhile, on February 26, 1862, Kamehameha IV ( 1834– 1863), Fourth King of Hawaii ( 1854– 1863), issued a commission to Captain Zenas Bent and Johnson B. Wilkinson, both Hawaiian citizens, to sail to Palmyra and to take possession of the atoll in the king's name and on April 15, 1862 it was formally annexed to the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Captain Bent sold his rights to Palmyra to Mr. Wilkinson on December 24, 1862 and from 1862 to 1885, Kalama Wilkinson owned the island which was divided in 1885 between three heirs, two of which immediately transferred their rights to a certain Wilcox (?) who, in turn, transferred them to the Pacific Navigation Company. The latter entity made an attempt to colonize the atoll by sending a married couple to live there between September 1885 and August 1886.

In 1898 Palmyra was annexed to the U.S. in conjunction with the overall U.S. annexation of Hawaii; on June 14, 1900 it became part of the then U.S. Territory of Hawaii. In the period preceding the formal annexation of the atoll by the U.S., the U.K. had shown interest for the atoll to become part of the "Guano Empire" of John T. Arundel & Co; and in 1889 the British had even formally annexed it. In order to end all further British attempts or contestations, a second, separate act of annexation of Palmyra by the U.S. was made in 1911.

Afterwards, by a series of agreements signed between 1888 and 1911, the Pacific Navigation Company transferred its interests to Henry Ernest Cooper Sr. ( 1857– 1929). The third heir of Kalama Wilkinson transferred his rights to a Mr. Ringer, whose children in turn also transferred their rights to Henry Ernest Cooper Sr. (s.a.) in 1912 and who then became the sole owner of the atoll.

On February 21, 1912 it was formally claimed by the U.S. government, still as part of Hawaii Territory.

In 1922 Cooper sold the whole atoll except some minor islets (the 5 "home islands") to Leslie and Ellen Fullard-Leo on August 19 for $15,000.00. The latter party established the Palmyra Copra Company to exploit the coconuts growing on the atoll. Their heirs continued as proprietors afterwards, except for a period of Navy administration during World War II.

In 1934, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, and Palmyra were placed under the Department of the Navy. When the U.S. Navy took over to use the atoll as a naval air station on 15 August 1941, the atoll was owned privately by Hawaiian and American citizens. It only had permanently resident government representatives, styled Island Commanders, from November 1939 to 1947.

After the war, the Fullard-Leos fought for the return of Palmyra all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and won in 1947. When Hawaii achieved statehood in 1959, Palmyra, which had been officially part of the City & County of Honolulu, was explicitly separated from the new state as an Incorporated Territory of the U.S., administered by U.S. Department of Interior.

In 1962, the U.S. Department of Defense used the atoll for an instrumentation site during high altitude atomic weapon tests over Johnston Island. There were more than 40 people living there to run the instrumentation and to service the technical staff. Problems occurred with the protection of wildlife from immature servicemen. The engineers and scientists there had their hands full keeping the servicemen away from the coconut crabs and birds.

In July 1990, Peter Savio of Honolulu took a lease on the atoll until the year 2065 and formed the Palmyra Development Company. In January 2000, the atoll was purchased by The Nature Conservancy for the purposes of coral reef conservation and research.

In November 2005, a worldwide team of scientists has joined with The Nature Conservancy to launch a new research station on the Palmyra Atoll in order to study climate change, disappearing coral reefs, invasive species and other global environmental threats.

And the Sea Will Tell

In 1974, a yachting couple from San Diego, California, Malcolm ("Mac") and Eleanor ("Muff") Graham, sailed to Palmyra hoping to find it deserted and to pass an idyllic year or more there. The Grahams overcame their disappointment of finding other "yachties" already on Palmyra and stayed. Their tragic decision was foreshadowed by the forbidding natural conditions on the atoll.

Also on Palmyra were Duane ("Buck") Walker (now known as Wesley G. Walker, the name he uses as a federal inmate) and Stephanie Stearns (now known to many as "Jennifer Jenkins"), who sailed there together from Hawaii. Walker was an ex-con fleeing the law for life on the Iola, a deteriorated, patched-together wooden sailboat. In contrast, the Grahams' ship, the Sea Wind, was a beautifully finished, impeccably outfitted ketch. The Grahams brought more than a year's supply of food, but Walker and Stearns quickly consumed their meager supplies. They were forced to plan a voyage in the rickety Iola against prevailing winds to Fanning, a nearby atoll, to restock. Although they started off friendly, tension soon arose between the Grahams, and Walker and Stearns.

Sometime between August 28 and August 30, 1974, Stearns said, the Grahams disappeared and the young couple found their Zodiac dinghy upside down. On September 11, 1974, after days of searching and waiting for the Grahams to return to their boat, Stearns said, Walker and Stearns scuttled the Iola and sailed for Hawaii on the Sea Wind. Once in Hawaii, the couple had the distinctive Sea Wind repainted on Kauai and renamed it, which according to boating superstition brings bad luck. This subterfuge merely aroused suspicion; acquaintances of the Grahams easily recognized the repainted Sea Wind. Walker and Stearns were arrested for their theft of the Sea Wind, for which both were tried and convicted, and served time.

On an early morning in 1981, by remarkable timing, another visitor to Palmyra found Muff Graham's skull and other skeletal remains in the surf there near to a large metal container. The remains showed signs of dismemberment and burning (possibly by Mac Graham's acetylene welding torch), and the body appeared to have been concealed underwater in the container. Buck Walker was tried and convicted of Muff Graham's murder and is serving his sentence. Walker is scheduled for a parole hearing in 2006, when he will be 68 years old.

As of 11/30/2006, Walker is being held in the Victorville Federal Prison, with an estimated release date of 12/4/2018. He will be 80 years old at that time.

Stearns was tried separately in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California in San Francisco, after her defense lawyer Vincent Bugliosi persuaded the court that publicity about the murders in Hawaii prevented the empaneling of an impartial jury there. Stearns was acquitted of the murder of Muff Graham and resumed her life in California in the telecommunications industry.

Mac Graham's body was never found. Vince Bugliosi recounts the story of the murders and trials in his 1991 book, And the Sea Will Tell ( ISBN 0-393-02919-0).