Katyn massacre

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: World War II

The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre ( Polish: zbrodnia katyńska, literally 'Katyń crime'), was a mass execution of Polish citizens ordered by Soviet authorities in 1940. Estimates of the number of Polish citizens executed at three mass-murder sites in the spring of 1940 range from 1,803 and 14,540 to 21,857 and over 28,000 on the high end. About 8,000 reserve officers taken prisoner during the 1939 invasion of Poland were killed, as were many civilians who had been arrested for allegedly being " intelligence agents, gendarmes, spies, saboteurs, landowners, factory owners and officials." Since Poland's conscription system required every unexempted university graduate to become a reserve officer, the Soviets were thus able to round up much of the Polish intelligentsia, as well as the Jewish, Ukrainian, Georgian and Belarusian intelligentsia of Polish citizenship.

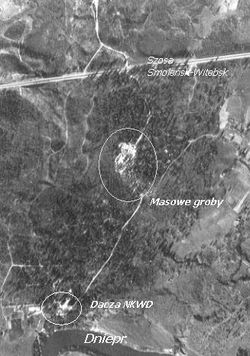

The term "Katyn massacre" originally referred to the massacre, at Katyn Forest near the village of Gnezdovo (located 12 miles (19 km) west of Smolensk, Russia), of Polish military officers confined at the Kozelsk prisoner-of-war camp. It is applied now also to the execution of prisoners of war held at Starobelsk and Ostashkov camps, and political prisoners in West Belarus and West Ukraine, shot on Stalin's orders at Katyn Forest, at the NKVD (Narodny Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del) Smolensk headquarters and at a slaughterhouse in the same city,, as well as at prisons in Kalinin (Tver), Kharkiv, Moscow, and other Soviet cities.

The 1943 discovery of mass graves at Katyn Forest by Germany, after its armed forces had occupied the site in 1941, precipitated a rupture of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the Polish government-in-exile in London. The Soviet Union continued to deny responsibility for the massacres until 1990, when it acknowledged that the NKVD secret police had in fact committed the massacres of over 22,000 Polish soldiers and intelligentsia and the subsequent cover-up. The Russian government has admitted Soviet responsibility for the massacres, although it does not classify them a war crime or an act of genocide, as this would have necessitated the prosecution of surviving perpetrators, which is what the Polish government has requested. Since "for 50 years, the Soviet Union concealed the truth" some, particularly in Russia, continue to believe the original Soviet explanation that it had been the Germans who had killed the Poles.

Preparations

On September 17, 1939 the Red Army invaded the territory of Poland from the east. This invasion took place while Poland had already sustained serious defeats in the wake of the German attack on the country that started on September 1, 1939; thus Soviets moved to safeguard their claims in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. In the wake of the Red Army's quick advance that met little resistance, between 250,000 and 454,700 Polish soldiers had become prisoners and were interned by the Soviets. About 250,000 were set free by the army almost on the spot, while 125,000 were delivered to the internal security services (the NKVD). The NKVD in turn quickly released 42,400 soldiers. The approximately 170,000 released were mostly soldiers of Ukrainian and Belorusian ethnicity serving in the Polish army. The 43,000 soldiers born in West Poland, now under German control, were transferred to the Germans. By November 19, 1939, NKVD had about 40,000 Polish POWs: about 8,500 officers and warrant officers, 6,500 police officers and 25,000 soldiers and NCOs who were still being held as POWs.

As early as September 19, 1939, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs and First Rank Commissar of State Security, Lavrenty Beria, ordered the NKVD to create a Directorate for Prisoners of War (or USSR NKVD Board for Prisoners of War and Internees, headed by State Security Captain Pyotr Soprunenko) to manage Polish prisoners. The NKVD took custody of Polish prisoners from the Red Army, and proceeded to organize a network of reception centers and transit camps and arrange rail transport to prisoner-of-war camps in the western USSR. The camps were located at Jukhnovo ( Babynino rail station), Yuzhe (Talitsy), Kozelsk, Kozelshchyna, Oranki, Ostashkov ( Stolbnyi Island on Seliger Lake near Ostashkov), Tyotkino rail station (56 mi/90 km from Putyvl), Starobielsk, Vologda ( Zaenikevo rail station) and Gryazovets.

Kozelsk and Starobielsk were used mainly for military officers, while Ostashkov was used mainly for Boy Scouts, gendarmes, police officers and prison officers. Prisoners at these camps were not exclusively military officers or members of the other groups mentioned, but also included Polish intelligentsia. The approximate distribution of men throughout the camps was as follows: Kozelsk, 5,000; Ostashkov, 6,570; and Starobelsk, 4,000. They totalled 15,570 men.

Once at the camps, from October 1939 to February 1940, the Poles were subjected to lengthy interrogations and constant political agitation by NKVD officers such as Vasily Zarubin. The Poles were encouraged to believe they would be released, but the interviews were in effect a selection process to determine who would live and who would die. According to NKVD reports, the prisoners could not be induced to adopt a pro-Soviet attitude. They were declared "hardened and uncompromising enemies of Soviet authority."

On March 5, 1940, pursuant to a note to Joseph Stalin from Lavrenty Beria, the members of the Soviet Politburo — Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Mikhail Kalinin, Kliment Voroshilov, Anastas Mikoyan and Beria — signed an order to execute 25,700 Polish "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries" kept at camps and prisons in occupied western Ukraine and Belarus.

Execution

In the period from April 3 to May 19, 1940, about 22,000 prisoners were executed: 14,700–15,570 from the three camps and about 11,000 prisoners in western parts of Belarus and Ukraine. A 1956 memo from KGB chief Alexander Shelepin to First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev confirmed 21,257 of these killings at the following sites: Katyn–4,421, Starobelsk Camp–3,820, Ostashkov Camp–6,311, other places of detention–7,305. Those who died at Katyn included an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 3,420 NCOs, seven chaplains, three landowners, a prince, 43 officials, 85 privates, and 131 refugees. Also among the dead were 20 university professors (including Stefan Kaczmarz); 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists as well as about 200 pilots. In all, the NKVD executed almost half the Polish officer corps. Altogether, during the massacre the NKVD murdered 14 Polish generals: Leon Billewicz (ret.), Bronisław Bohatyrewicz (ret.), Xawery Czernicki (admiral), Stanisław Haller (ret.), Aleksander Kowalewski (ret.), Henryk Minkiewicz (ret.), Kazimierz Orlik-Łukoski, Konstanty Plisowski (ret.), Rudolf Prich (murdered in Lviv), Franciszek Sikorski (ret.), Leonard Skierski (ret.), Piotr Skuratowicz, Mieczysław Smorawiński and Alojzy Wir-Konas (promoted posthumously). A mere 395 prisoners were saved from the slaughter, among them Stanisław Swianiewicz. They were taken to the Yukhnov camp and then down to Gryazovets. They were the only ones who escaped death.

Up to 99% of the remaining prisoners were subsequently murdered. People from Kozelsk were murdered in the usual mass murder site of Smolensk country, called Katyn forest; people from Starobielsk were murdered in the inner NKVD prison of Kharkov and the bodies were buried near Pyatikhatki; and police officers from Ostashkov were murdered in the inner NKVD prison of Kalinin (Tver) and buried in Miednoje (Mednoye).

Detailed information on the executions in the Kalinin NKVD prison was given during the hearing by Dmitrii S. Tokarev, former head of the Board of the District NKVD in Kalinin. According to Tokarev, the shooting started in the evening and ended at dawn. The first transport on April 4, 1940, carried 390 people, and the executioners had a hard time killing so many people during one night. The following transports were no greater than 250 people. The executions were usually performed with German-made Walther-type pistols supplied by Moscow.

The killings were methodical. After the condemned's personal information was checked, he was handcuffed and led to a cell insulated with a felt-lined door. The sounds of the murderers were also masked by the operation of loud machines (perhaps fans) throughout the night. After being taken into the cell, the victim was immediately shot in the back of the head. His body was then taken out through the opposite door and laid in one of the five or six waiting trucks, whereupon the next condemned was taken inside. The procedure went on every night, except for the May Day holiday. Near Smolensk, the Poles, with their hands tied behind their backs, were led to the graves and shot in the neck.

After the execution was carried out, there were still more than 22,000 of the former Polish soldiers in NKVD labor camps. According to Beria's report, by November 2, 1940 his department had 2 generals, 39 lieutenant-colonels and colonels, 222 captains and majors, 691 lieutenants, 4022 warrant officers and NCOs and 13,321 enlisted men captured during the Polish campaign. Plus 3,300 Polish soldiers were captured during the annexation of Lithuania, where they were kept interned since September 1939.

Discovery

The question of the Polish prisoners' fate was first raised soon after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, when the Polish government-in-exile and the Soviet government signed the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement in which they agreed to cooperate against Germany, and so that a Polish army on Soviet territory was to be formed. When the Polish general Władysław Anders began organizing this army, he requested information about the Polish officers. During a personal meeting Stalin assured him and Władysław Sikorski, the Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile, that all the Poles had been freed, and the fact that not all can be accounted is due to the fact that the Soviets "lost track" of them in Manchuria.

The fate of the missing prisoners remained unknown until April 1943 when the German Wehrmacht discovered the mass grave of more than 4,000 Polish military reserve officers in the forest on Goat Hill near Katyn. Joseph Goebbels saw this discovery as an excellent tool to drive a wedge between Poland, Western Allies, and the Soviet Union. On April 13 Berlin Radio broadcast to the world that the German military forces in the Katyn forest near Smolensk had uncovered "a ditch ... 28 metres long and 16 metres wide [92 ft by 52 ft], in which the bodies of 3,000 Polish officers were piled up in 12 layers." The broadcast went on to charge the Soviets with carrying out the massacre in 1940.

The Germans assembled and brought in a European commission consisting of twelve forensic experts and their staffs. With the exception of a Swiss from the University of Geneva, all were from lands then occupied by Germany. After the war, all of the experts, save for a Bulgarian and a Czech, reaffirmed their 1943 finding of Soviet guilt.

The Katyn Massacre was beneficial to Nazi Germany, which it used to discredit the Soviet Union. Goebbels wrote in his diary on April 14, 1943: "We are now using the discovery of 12,000 Polish officers, murdered by the GPU, for anti-Bolshevik propaganda on a grand style. We sent neutral journalists and Polish intellectuals to the spot where they were found. Their reports now reaching us from ahead are gruesome. The Fuehrer has also given permission for us to hand out a drastic news item to the German press. I gave instructions to make the widest possible use of the propaganda material. We shall be able to live on it for a couple weeks" The Germans had succeeded in discrediting the Soviet Government in the eyes of the world and briefly raised the spectre of a communist monster rampaging across the territories of Western civilization; moreover they had forged the unwilling General Sikorski into a tool which could threaten to unravel the alliance between the Western Allies and Soviet Union.

The Soviet government immediately denied the German charges and claimed that the Polish prisoners of war had been engaged in construction work west of Smolensk and consequently were captured and executed by invading German units in August 1941. The Soviet response on April 15 to the German initial broadcast of April 13, prepared by the Soviet Information Bureau stated that "[...]Polish prisoners-of-war who in 1941 were engaged in country construction work west of Smolensk and who [...] fell into the hands of the German-Fascist hangmen [...]."

The Allies were aware that the Nazis had found a mass grave as the discovery transpired, via radio transmissions intercepted and decrypted by Bletchley Park. Germans and the international commission, which was invited by Germany, investigated the Katyn corpses and soon produced physical evidence that the massacre took place in early 1940, at a time when the area was still under Soviet control.

In April 1943, when the Polish government in exile insisted on bringing this matter to the negotiation table with Soviets and on an investigation by the International Red Cross, Stalin accused the Polish government in exile of collaborating with Nazi Germany, broke diplomatic relations with it, and started a campaign to get the Western Allies to recognize the alternative Polish pro-Soviet government in Moscow led by Wanda Wasilewska. Sikorski, whose uncompromising stance on that issue was beginning to create a rift between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, died suddenly two months later. The cause of his death is still disputed.

Actions taken by the Soviet Union

When in September 1943 Goebbels was informed that the German Army had to withdraw from the Katyn area, he entered a prediction in his diary. His entry for September 29, 1943 reads: "Unfortunately we have had to give up Katyn. The Bolsheviks undoubtedly will soon 'find' that we shot 12,000 Polish officers. That episode is one that is going to cause us quite a little trouble in the future. The Soviets are undoubtedly going to make it their business to discover as many mass graves as possible and then blame it on us."

Indeed, having retaken the Katyn area almost immediately after the Red Army had recaptured Smolensk, the Soviet Union, led by the NKVD, began a cover-up. A cemetery the Germans had permitted the Polish Red Cross to build was destroyed and other evidence removed. In January 1944, the Soviet Union sent the "Special Commission for Determination and Investigation of the Shooting of Polish Prisoners of War by German-Fascist Invaders in Katyn Forest," (U.S.S.R. Spetsial'naya Kommissiya po Ustanovleniyu i Rassledovaniyu Obstoyatel'stv Rasstrela Nemetsko-Fashistskimi Zakhvatchikami v Katynskom Lesu) to investigate the incidents again. The so-called "Burdenko Commission", headed by Nikolai Burdenko, the President of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR, exhumed the bodies again and reached the conclusion that the shooting was done in 1941, when the Katyn area was under German occupation. No foreign personnel, including the Polish communists, were allowed to join the Burdenko Commission, whereas the Nazi German investigation had allowed wider access to both international press and organizations (like the Red Cross) and even used Polish workers, like Józef Mackiewicz.

Response to the massacre by the Western Allies

The Western Allies had an implicit, if unwilling, hand in the cover-up in their endeavour not to antagonise a then ally, the Soviet Union. The resulting Polish-Soviet crisis was beginning to threaten the vital alliance with the Soviet Union at a time when the Poles' importance to the Allies, essential in the first years of the war, was beginning to fade due to the entry into the conflict of the military and industrial giants, the Soviet Union and the United States. In retrospective review of records, it is clear that both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt were increasingly torn between their commitments to their Polish ally, the uncompromising stance of Sikorski and the demands by Stalin and his diplomats.

In private, Churchill agreed that the atrocity was likely carried out by the Soviets. According to the note taken by Count Raczyński, Churchill admitted on April 15 during a conversation with General Sikorski: "Alas, the German revelations are probably true. The Bolsheviks can be very cruel." However at the same time, on April 24 Churchill assured the Soviets: "We shall certainly oppose vigorously any 'investigation' by the International Red Cross or any other body in any territory under German authority. Such investigation would be a fraud and its conclusions reached by terrorism." Unofficial or classified UK documents concluded that Soviet guilt was a "near certainty", but the alliance with the Soviets was deemed to be more important than moral issues, thus official version supported the Soviet version, up to censoring the contradictory accounts. Churchill's own post-war account of the Katyn affair is laconic. In his memoirs, he quotes the 1944 Soviet inquiry into the massacre, which predictably proved that the Germans had committed the crime, and adds, "belief seems an act of faith."

In the United States, a similar line was taken notwithstanding that two official intelligence reports into Katyn massacre were produced that contradicted the official position.

In 1944 Roosevelt assigned Army Captain George Earle, his special emissary to the Balkans, to compile information on Katyn which he did using contacts in Bulgaria and Romania. He concluded that the Soviet Union committed the massacre. After consulting with Elmer Davis, the director of the Office of War Information, Roosevelt rejected that conclusion, saying that he was convinced of Nazi Germany's responsibility, and ordered Earle's report suppressed. When Earle formally requested permission to publish his findings, the President gave him a written order to desist. Earle was reassigned and spent the rest of the war in American Samoa.

A further report in 1945 supporting the same conclusion was produced and stifled. In 1943 two US POWs – Lt. Col. Donald B. Stewart and Col. John H. Van Vliet – had been taken by Nazi Germans to Katyn in 1943 for an international news conference. Later, in 1945, Van Vliet wrote a report concluding that the Soviets, not the Germans, were responsible. He gave the report to Maj. Gen. Clayton Bissell, Gen. George Marshall's assistant chief of staff for intelligence, who destroyed it. During the 1951–1952 investigation Bissell defended his action before Congress, contending that it was not in the US interest to embarrass an ally whose forces were still needed to defeat Japan.

Trials

From December 29, 1945 to January 5, 1946, ten officers of the German Wehrmacht – Karl Hermann Strüffling, Heinrich Remmlinger, Ernst Böhm, Eduard Sonnenfeld, Herbard Janike, Erwin Skotki, Ernst Geherer, Erich Paul Vogel, Franz Wiese, and Arno Dürer – were tried by a Soviet military court in Leningrad. They were falsely charged for an alleged role in the Katyn massacre. The first seven officers were sentenced to death and executed by public hanging on the same day. The other three were sentenced to hard labor, Vogel and Wiese to 20 year terms each and Dürer to 15 years. Dürer is said to have pleaded guilty at the trial and to have returned to Germany later, the fate of the others sentenced to hard labor remains unknown.( dubious—see talk page)

In 1946, the chief Soviet prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, Roman A. Rudenko, tried to indict Germany for the Katyn killings, stating that "one of the most important criminal acts for which the major war criminals are responsible was the mass execution of Polish prisoners of war shot in the Katyn forest near Smolensk by the German fascist invaders", but dropped the matter after the United States and United Kingdom refused to support it and German lawyers mounted an embarrassing defense.

More specifically, presented by the Soviet charge the Burdenko report, in spite of the reservesof the Anglo-Saxons, was accepted on grounds of the article 21 and coded as URSS-54. The German White Book of 1943 was accepted on grounds of the article 19 with, as had underlined it the president of the court, a potential convincing value; the course of the debates would make this adjective pointless. The intransigence of the Soviets to reveal Katyn in the bill of indictment was driven by the final objective: to quote it in the verdict. To this end, summoning of some witnesses was refused.

However, the problem to be addressed by the court was not to allot the responsibility for the massacre to Germany or the Soviet Union, but to attribute the crime to at least one of the twenty four dignitaries of the nazi state. The task of the charge was thus to establish a link between the reproached acts and the defendants. On hearings, however, the Soviet prosecutor proved to be unable to name the person in charge for the execution of the massacre, as well as the supposed guilty among the defendants.

In spite of this bankruptcy of the charge, Nikitchenko tried to make pass in force the Soviet point of view and did not hesitate to claim the inadequacy of the statutes of the court. This failed and the name of Katyn did not appear in the verdict.

Perception of the massacre in the Cold War

In 1951–52, in the background of the Korean War, a U.S. Congressional investigation chaired by Rep. Ray J. Madden and known as the Madden Committee investigated the Katyn massacre. It charged that the Poles had been killed by the Soviets and recommended that the Soviets be tried before the International World Court of Justice. The committee was however less conclusive on the issue of alleged American cover up.

The question of responsibility remained controversial in the West as well as behind the Iron Curtain. For example, in the United Kingdom in the late 1970s, plans for a memorial to the victims bearing the date 1940 (rather than 1941) were condemned as provocative in the political climate of the Cold War.

It has been sometimes speculated that the choice made in 1969 for the location of the BSSR's war memorial at the former Belarusian village named Khatyn, a site of a 1943 Nazi massacre in which the entire village with its whole population was burned, have been made to cause confusion with Katyn. The two names are similar or identical in many languages.

In Poland Communist authorities covered up the matter in concord with Soviet propaganda, deliberately censoring any sources that might shed some light on the Soviet crime. Katyn was a forbidden topic in postwar Poland. Not only did government censorship suppress all references to it, but even mentioning the atrocity was dangerous. Katyn became erased from Poland's official history, but it could not be erased from historical memory. In 1981, Polish trade union Solidarity erected a memorial with the simple inscription "Katyn, 1940" but it was confiscated by the police, to be replaced with an official monument "To the Polish soldiers – victims of Hitlerite fascism – reposing in the soil of Katyn". Nevertheless, every year on Zaduszki, similar memorial crosses were erected at Powązki cemetery and numerous other places in Poland, only to be dismantled by the police overnight. The Katyn subject remained a political taboo in Poland until the fall of the Eastern bloc in 1989.

Revelations

From the late 1980s, pressure was put not only on the Polish government, but on the Soviet one as well. Polish academics tried to include Katyn in the agenda of the 1987 joint Polish-Soviet commission to investigate censored episodes of the Polish-Russian history. In 1989 Soviet scholars revealed that Joseph Stalin had indeed ordered the massacre, and in 1990 Mikhail Gorbachev admitted that the NKVD had executed the Poles and confirmed two other burial sites similar to the site at Katyn: Mednoje and Pyatikhatki.

On 30 October 1989, Gorbachev allowed a delegation of several hundred Poles, organized by a Polish association named Families of Katyń Victims, to visit the Katyn memorial. This group included former U.S. national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski. A mass was held and banners hailing the Solidarity movement were laid. One mourner affixed a sign reading "NKVD" on the memorial, covering the word "Nazis" in the inscription such that it read "In memory of Polish officers murdered by the NKVD in 1941." Several visitors scaled the fence of a nearby KGB compound and left burning candles on the grounds. Brzezinski commented that:

- "It isn't a personal pain which has brought me here, as is the case in the majority of these people, but rather recognition of the symbolic nature of Katyń. Russians and Poles, tortured to death, lie here together. It seems very important to me that the truth should be spoken about what took place, for only with the truth can the new Soviet leadership distance itself from the crimes of Stalin and the NKVD. Only the truth can serve as the basis of true friendship between the Soviet and the Polish peoples. The truth will make a path for itself. I am convinced of this by the very fact that I was able to travel here."

Brzezinski further stated that "The fact that the Soviet government has enabled me to be here – and the Soviets know my views – is symbolic of the breach with Stalinism that perestroika represents." His remarks were given extensive coverage on Soviet television. At the ceremony he placed a bouquet of red roses bearing a handwritten message penned in both Polish and English: "For the victims of Stalin and the NKVD. Zbigniew Brzezinski."

On 13 April 1990, the forty-seventh anniversary of the discovery of the mass graves, the USSR formally expressed "profound regret" and admitted Soviet secret police responsibility. That day is also an International Day of Katyn Victims Memorial (Światowy Dzień Pamięci Ofiar Katynia).

After Poles and Americans discovered further evidence in 1991 and 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin released and transferred to the new Polish president, former Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa, top-secret documents from the sealed package no. 1. Among the documents included Lavrenty Beria's March 1940 proposal to shoot 25,700 Poles from Kozelsk, Ostashkov and Starobels camps, and from certain prisons of Western Ukraine and Belarus with the signature of Stalin (among others); an excerpt from the Politburo shooting order of March 5 1940; and Aleksandr Shelepin's March 3, 1959 note to Nikita Khrushchev, with information about the execution of 21,857 Poles and with the proposal to destroy their personal files.

The investigations that indicted the German state rather than the Soviet state for the killings are sometimes used to impeach the Nuremberg Trials in their entirety, often in support of Holocaust denial, or to question the legitimacy and/or wisdom of using the criminal law to prohibit Holocaust denial. Still, there are some who deny Soviet guilt, call the released documents fakes, and try to prove that Poles were shot by Germans in 1941.

On the opposing sides there are allegations that the massacre was part of wider action coordinated by Nazi Germany and Soviet Union, or that Germans at least knew of Katyn beforehand. The reason for these allegations is that Soviet Union and Nazi Germany added on 28 September, a secret supplementary protocol to the German-Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, in which they stated that Both parties will tolerate in their territories no Polish agitation which affects the territories of the other party. They will suppress in their territories all beginnings of such agitation and inform each other concerning suitable measures for this purpose, after which in 1939–1940 a series of conferences by NKVD and Gestapo were organised in the town of Zakopane. The aim of these conferences was to coordinate the killing and the deportation policy and exchange experience. A University of Cambridge professor of history George Watson believes that the fate of Polish prisoners was discussed at the conference. This theory surfaces in Polish media, where it is also pointed out that similar massacre of Polish elites ( AB-Aktion) were taking place in the exact time and with similar methods in German occupied Poland.

In June 1998, Yeltsin and Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski agreed to construct memorial complexes at Katyn and Mednoye, the two NKVD execution sites on Russian soil. However in September that year Russians also raised the issue of Soviet POWs death in the Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919-1924). About 15,000–20,000 POWs died in those camps due to epidemic (especially Spanish flu), however some Russian officials argued that it was 'a genocide comparable to Katyń'. Similar claim was raised in 1994; such attempts are seen by some, particulary in Poland, as a highly provocative Russian attempt to create an 'anti-Katyn' and 'balance the historical equation'.

During Kwaśniewski's visit to Russia in September 2004, Russian officials announced that they are willing to transfer all the information on the Katyn Massacre to the Polish authorities as soon as it is declassified. In March 2005 Russian authorities ended the decade-long investigation with no one charged. Russian Chief Military Prosecutor Alexander Savenkov put the final Katyn death toll at 14,540 and declared that the massacre was not a genocide – a war crime – or a crime against humanity but a military crime for which the 50-year term of limitation has expired and that consequently there is absolutely no basis to talk about this in judicial terms. Despite earlier declarations, President Vladimir Putin's government refused to allow Polish investigators to travel to Moscow in late 2004 and 116 out of 183 volumes of files gathered during the Russian investigation, as well as the decision to put an end to it, were classified.

Because of that, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance has decided to open its own investigation. Prosecution team head Leon Kieres said they would try to identify those involved in ordering and carrying out the killings. In addition, on March 22, 2005 the Polish Sejm unanimously passed an act, requesting the Russian archives to be declassified. The Sejm also requested Russia to classify the Katyn massacre as genocide: "On the 65th anniversary of the Katyn murder the Senate pays tribute to the murdered, best sons of the homeland and those who fought for the truth about the murder to come to light, also the Russians who fought for the truth, despite harassment and persecution" – the resolution said. The resolution stressed that the authorities of Russia "seek to diminish the burden of this crime by refusing to acknowledge it was genocide and refuse to give access to the records of the investigation into the issue, making it difficult to determine the whole truth about the murder and its perpetrators."

Russia and Poland remained divided on the legal qualification of the Katyn crime, with the Poles considering it a case of genocide and demanding further investigations, as well as complete disclosure of Soviet documents.

Katyn in fiction

The Katyn massacre is a major plot element in many works of fiction, for example, in the W.E.B. Griffin novel The Lieutenants which is part of the Brotherhood of War series, as well as in the novel and film Enigma. Polish poet Jacek Kaczmarski has dedicated one of his sung poems to this event. The award-winning Polish film director Andrzej Wajda begun work on a film depicting the event in 2006, the production title of which is "Post-Mortem: The Katyn story". The film will recount the fate of some of the women - mothers, wives and daughters - of the Polish officers slaughtered by the Soviets. Some Katyn Forest scenes will be re-enacted. The screenplay is based on Andrzej Mularczyk's book of the same title. The film is produced by Akson Studio, and planned for release in the Autumn of 2007.

Original documents

Original documents related to the Katyn massacre: