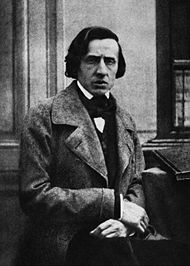

Frédéric Chopin

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Performers and composers

Frédéric Chopin ( Polish: Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin, sometimes Szopen; French: Frédéric François Chopin; English surname pronunciation: IPA: /ʃoʊpæn/ or /ʃoʊpæ̃/; March 1, 1810, Żelazowa Wola – October 17, 1849, Paris) was a Polish piano composer of the Romantic period. He is widely regarded as one of the most famous, influential and prolific composers for piano.

Chopin was born in the village of Żelazowa Wola, Poland, to a Polish mother and French- expatriate father. Hailed in his homeland as a child prodigy, at age twenty Chopin left for Paris. There he made a career as performer, teacher and composer, and adopted the French version of his given names, "Frédéric-François." From 1837 to 1847 he had a turbulent relationship with the French writer George Sand (Aurore Dudevant). Always in frail health, at 39 he succumbed to pulmonary tuberculosis.

All of Chopin's extant work includes the piano in some role (predominantly as a solo instrument), and his compositions are widely considered to be among the pinnacles of the piano's repertoire. Although his music is among the most technically demanding for the instrument, Chopin's style emphasizes nuance and expressive depth rather than mere technical display. He invented some musical forms, such as the ballade, but his most significant innovations were within existing structures such as the piano sonata, waltz, nocturne, étude, and prelude. His works are often cited as being among the mainstays of Romanticism in 19th-century classical music. Additionally, Chopin was the first western classical composer to imbue Slavic elements into his music; to this day his mazurkas and polonaises are the cornerstone of Polish nationalistic classical music.

Life

Chopin was born in Żelazowa Wola, near Sochaczew in the Masovia region, which was part of the Duchy of Warsaw. He was born to Mikołaj (Nicolas) Chopin, a Frenchman of distant Polish ancestry from Lorraine who had adopted Poland as his homeland when he moved there in 1787. Nicolas had married a woman from an upper-class but impoverished Polish family, Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska.

According to the composer's family, Chopin was born March 1, 1810. There is no known birth certificate. His baptismal certificate lists his birthdate as February 22, 1810, but this was most likely an error on the part of the priest.

Formative years

In October 1810, when Frédéric was seven months old, the family moved to Warsaw, where the father took a position as teacher of French language at a high school housed in the Saxon Palace. The family lived on the palace grounds.

Young Chopin, like his sisters, received his first piano lessons from his mother. His musical talent was early apparent, and he gained a reputation in Warsaw as a "second Mozart." At age seven he was already the author of two polonaises ( G minor and B flat major), the first being published in the engraving workshop of Father Cybulski, director of a School of Organists and one of the few music publishers in Poland. The prodigy was featured in the Warsaw newspapers, and "little Chopin" became an attraction at receptions given in the capital's aristocratic salons. He also began giving public charity concerts. He is said to once have been asked what he thought the audience liked best; seven-year-old Chopin replied, "My shirt collar." He first appeared publicly as a pianist when he was eight.

Chopin received his first professional piano lessons, in 1816-22, from Wojciech Żywny. Chopin later spoke highly of Żywny, although the youngster's skills soon surpassed those of his teacher. The further development of Chopin's talent was supervised by Wilhelm Würfel. This renowned pianist, a professor at the Warsaw Conservatory, gave Chopin valuable though irregular lessons in playing the organ, and possibly also the piano. From 1823 to 1826 Chopin attended the Warsaw Lyceum, a high school where his father taught.

In the autumn of 1826, Chopin began studying music theory, figured bass and composition with the composer Józef Elsner at the Warsaw Conservatory. Chopin's contact with Elsner may date to as early as 1822, and it is certain that Elsner was giving Chopin informal guidance by 1823. Chopin completed a normal three-year course at the conservatory in 1829.

That same year in Warsaw, Chopin heard Niccolò Paganini play, and he also met the German pianist and composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel. It was also in 1829 that Chopin met his first love, a singing student named Konstancja Gładkowska. This inspired Chopin to put the melody of the human voice into his works.

In August 1829, three weeks after leaving the Warsaw Conservatory, Chopin made a brilliant debut in Vienna. He gave two piano performances and received many very favorable reviews, along with others that criticized the small tone that he produced from the piano.

In Warsaw in December 1829 he performed the premiere of his Piano Concerto in F minor at the Merchants' Club. He gave the first performance of his other piano concerto, in E minor, at the National Theatre on March 17, 1830.

On November 2, 1830, Chopin left Warsaw to give concerts in western Europe, never to return to Poland. At month's end the November 1830 Uprising broke out, and his traveling companion Titus Woyciechowski went home to take part. Chopin stayed in Vienna, tortured by anxiety for his loved ones, then visited Munich and Stuttgart (where he learned of Poland's occupation by the Russian army; see Congress Poland) and arrived in Paris by October 1831. He had already composed a body of important compositions, including his two piano concertos and some of his Études Op. 10.

Paris

In Paris, Chopin was welcomed by eminent Polish exiles and by leading artists such as Heinrich Heine, Alfred de Vigny and Eugène Delacroix. He was introduced to some of the foremost pianists of the day, including Friedrich Kalkbrenner, Ferdinand Hiller and Franz Liszt, and he formed personal friendships with composers Hector Berlioz, Felix Mendelssohn, Charles-Valentin Alkan and Vincenzo Bellini (beside whom he is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery). Chopin's music was already admired by many of his composer contemporaries, among them Robert Schumann who, in his review of the Variations on "La ci darem la mano" (from Mozart's opera Don Giovanni), Op. 2, wrote: "Hats off, gentlemen! A genius."

During his years in Paris, Chopin participated in a number of concerts. The programs provide some idea of the richness of Parisian artistic life during this period, such as the concert on March 23, 1833, in which Chopin, Liszt and Hiller played the solo parts in a performance of Johann Sebastian Bach's concerto for three harpsichords, and the concert on March 3, 1838, when Chopin, Alkan, Alkan's teacher Pierre Joseph Zimmerman and Chopin's pupil Adolphe Gutman played Alkan's 8-hand arrangement of Beethoven's 7th symphony.

A distinguished English amateur described seeing Chopin at a salon:

| “ | Imagine a delicate man of extreme refinement of mien and manner, sitting at the piano and playing with no sway of the body and scarcely any movement of the arms, depending entirely upon his narrow feminine hand and slender fingers. The wide arpeggios in the left hand, maintained in a continuous stream of tone by the strict legato and fine and constant use of the damper pedal, formed a harmonious substructure for a wonderfully poetic cantabile. His delicate pianissimo, the ever-changing modifications of tone and time ( tempo rubato) were of indescribable effect. Even in energetic passages he scarcely ever exceeded an ordinary mezzoforte. | ” |

From Paris, Chopin made various visits and tours. In 1834, with Hiller, he visited a Rhenish Music Festival at Aachen organized by Ferdinand Ries. Here Chopin and Hiller met up with Mendelssohn, and the three went on to visit Düsseldorf, Koblenz and Cologne, enjoying each other's company and learning and playing music together.

In 1835 Chopin visited his family in Karlsbad, whence he accompanied his parents to Děčín where they lived. He returned to Paris via Dresden, where he stayed for some weeks, and then Leipzig where he met up with Mendelssohn, Schumann and Clara Wieck. However, on the return journey he had a severe bronchial attack — so bad that he was reported dead in some Polish newspapers.

In 1836 Chopin became engaged to a seventeen-year-old Polish girl, Maria Wodzińska, whose mother insisted that the engagement be kept secret. The following year the engagement was called off by her family.

Chopin and Sand

In 1836, at a party hosted by Countess Marie d'Agoult, mistress of fellow-composer Franz Liszt, Chopin met Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin, Baroness Dudevant, better known by her pseudonym, George Sand. She was a French Romantic writer noted for her numerous love affairs with Prosper Mérimée, Alfred de Musset (1833–34), her secretary Alexandre Manceau (1849–65) and others.

Chopin initially did not find her attractive. "Something about her repels me," he told his family. Sand, however, in an extraordinary June 1837 letter to her friend Count Wojciech Grzymała, debated whether to let Chopin go with his fiancée Maria Wodzińska or to abandon another affair in order to begin a relationship with Chopin. Sand had strong feelings for Chopin and pursued him until a relationship developed.

A notable episode in their time together was a turbulent and miserable winter on Mallorca (1838–1839), where they had problems finding habitable accommodation and ended up lodging in the scenic but stark and cold Valldemossa monastery. Chopin also had problems having his Pleyel piano sent to him. It arrived from Paris after a great delay, to be stuck at Spanish customs, which demanded a large import duty. He could use it for little more than three weeks; the rest of the time he had to compose on a rickety rented piano to complete his Preludes (Op. 28).

During the winter, the bad weather had such a serious effect on Chopin's health and his chronic lung disease that – to save his life – he, George Sand and her two children were compelled to return first to the Spanish mainland where they reached Barcelona, and then to Marseille where they stayed for a few months to recover. Although his health improved, he never completely recovered from this bout. He complained, with his habitual wit, about the incompetence of the doctors in Mallorca: "The first said I was going to die; the second said I had breathed my last; and the third said I was already dead."

Chopin spent the summers of 1839 until 1843 at Sand's estate in Nohant. These were quiet but productive days during which Chopin composed many works. They included his great Polonaise in A-flat major, Op.53 "Heroic," still one of his most famous pieces. On Chopin's return to Paris in 1839, he met the pianist and composer Ignaz Moscheles.

In 1845 a serious problem emerged in Chopin's relationship with Sand at the same time as a further deterioration occurred in his health. Their relationship was further soured in 1846 by family problems; this was the year in which Sand published Lucrezia Floriani, which is quite unfavorable to Chopin. The story is about a rich actress and a prince with weak health, and it is possible to interpret the main characters as Sand and Chopin. In 1847 the family problems finally brought an end to their relationship.

Death and funeral

In 1848 Chopin gave his last concert in Paris, and visited England and Scotland with his student and admirer Jane Stirling. They reached London in November, and although Chopin managed to give some concerts and salon performances, he was severely ill. He returned to Paris, where in 1849 he became unable to teach or perform. His sister Ludwika nursed him in his apartment at Place Vendôme, 12, where he died in the small hours of October 17. Later that morning, a death mask and a cast of Chopin's hands were made by the young sculptor, Jean Baptiste Clesinger.

Before his funeral, Chopin's heart was removed, to be taken by his sister in an urn to Warsaw, where it remains sealed within a pillar of the Holy Cross Church (Kościół Świętego Krzyża) on Krakowskie Przedmieście.

Chopin had requested that Mozart's Requiem be sung at his funeral. The Requiem has major parts for female singers, but the chosen church, the Church of the Madeleine, had never permitted female singers in its choir. The funeral was delayed for almost two weeks, until the church finally relented and granted Chopin's final wish, provided the female singers remained behind a black velvet curtain. The funeral was held on 30 October and was attended by nearly three thousand people. The soloists in the Requiem included the bass Luigi Lablache, who had sung the same work at the funeral of Beethoven and also sang at the funeral of Bellini. Preludes No. 4 in E minor and No. 6 in B minor were also played. He was buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, also at his own request. At the graveside, the Funeral March from the Sonata Op. 35 was played, in Napoléon Henri Reber's instrumentation. Later, some of Chopin's Polish friends journeyed to Paris with a jar of earth from their native land and scattered it over his grave, so that Chopin would lie under Polish soil. His grave attracts numerous visitors and is invariably festooned with flowers, even in the dead of winter.

Music

Chopin's music for the piano combined a unique rhythmic sense (particularly his use of rubato), frequent use of chromaticism, and counterpoint. This mixture produces a particularly fragile sound in the melody and the harmony, which are nonetheless underpinned by solid and interesting harmonic techniques. He took the new salon genre of the nocturne, invented by Irish composer John Field, to a deeper level of sophistication. Three of his twenty-one nocturnes were only published after his death in 1849, contrary to his wishes. He also endowed popular dance forms, such as the Polish mazurka and the Viennese waltz, with a greater range of melody and expression. Chopin was the first to write ballades and scherzi as individual pieces. Chopin also took the example of Bach's preludes and fugues, transforming the genre in his own preludes.

Several of Chopin's pieces have become very well known — for instance the Revolutionary Étude (Op. 10, No. 12), the Minute Waltz (Op. 64, No. 1), and the third movement of his Funeral March sonata (Op. 35), which is often used as an iconic representation of grief. The Revolutionary Étude was not written with the failed Polish uprising against Russia in mind; it merely appeared at that time. The Funeral March was written before the rest of the sonata within which it is contained, but the exact occasion is not known; it appears not to have been inspired by any specific personal bereavement. Other melodies have been used as the basis of popular songs, such as the slow section of the Fantaisie-Impromptu (Op. 66) and the first section of the Étude Op. 10 No. 3. These pieces often rely on an intense and personalised chromaticism, as well as a melodic curve that resembles the operas of Chopin's day — the operas of Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, and especially Bellini. Chopin used the piano to re-create the gracefulness of the singing voice, and talked and wrote constantly about singers.

Chopin's style and gifts became increasingly influential. Robert Schumann was a huge admirer of Chopin's music — although the feeling was not reciprocated — and he took melodies from Chopin and even named a piece from his suite Carnaval after Chopin.

Franz Liszt, another great admirer and personal friend of the composer, transcribed for piano six of Chopin's Polish songs. However, one myth about Liszt's admiration for Chopin should be dispelled. In 1853, Liszt published a piano suite called Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses. The seventh movement, Funérailles, is subtitled "October 1849". That this was the month of Chopin's death, and that the middle section seems to be modelled upon the famous octave trio section of Chopin's Polonaise in A-flat major, Op. 53, have led many to presume that Liszt wrote the piece in memory of Chopin. However, Liszt denied this, saying the piece had been inspired by the deaths of three of his Hungarian compatriots in the same month.

Chopin performed his own works in concert halls but most often in his salon for friends. Only later in life, as his disease progressed, did Chopin give up public performance altogether.

Chopin's technical innovations also became influential. His Préludes (Op. 28) and Études (Opp. 10 and 25) rapidly became standard works, and inspired both Liszt's Transcendental Études and Schumann's Symphonic Études. Alexander Scriabin was also strongly influenced by Chopin; for example, his 24 Preludes, Op. 11 are inspired by Chopin's Op. 28.

Jeremy Siepmann, in his biography of the composer, named a list of pianists he believed to have made recordings of works by Chopin generally acknowledged to be among the greatest Chopin performances ever preserved: Vladimir de Pachmann, Raoul Pugno, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Moriz Rosenthal, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alfred Cortot, Ignaz Friedman, Raoul Koczalski, Arthur Rubinstein, Mieczysław Horszowski, Claudio Arrau, Vlado Perlemuter, Vladimir Horowitz, Dinu Lipatti, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Martha Argerich, Maurizio Pollini, Murray Perahia, Krystian Zimerman, Evgeny Kissin.

Rubinstein said the following about Chopin's music and its universality:

| “ | Chopin was a genius of universal appeal. His music conquers the most diverse audiences. When the first notes of Chopin sound through the concert hall there is a happy sigh of recognition. All over the world men and women know his music. They love it. They are moved by it. Yet it is not "Romantic music" in the Byronic sense. It does not tell stories or paint pictures. It is expressive and personal, but still a pure art. Even in this abstract atomic age, where emotion is not fashionable, Chopin endures. His music is the universal language of human communication. When I play Chopin I know I speak directly to the hearts of people! | ” |

Style

Although Chopin lived in the 1800s, he was educated in the tradition of Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart and Clementi; he even used Clementi's piano method with his own students. He was also influenced by Hummel's development of virtuoso, yet Mozartian, piano technique. One of his students, Friederike Muller, wrote the following in her diary about Chopin's playing style:

| “ | His playing was always noble and beautiful; his tones sang, whether in full forte or softest piano. He took infinite pains to teach his pupils this legato, cantabile style of playing. His most severe criticism was "He—or she—does not know how to join two notes together." He also demanded the strictest adherence to rhythm. He hated all lingering and dragging, misplaced rubatos, as well as exaggerated ritardandos ... and it is precisely in this respect that people make such terrible errors in playing his works. | ” |

Chopin's polonaises brought the musical form to a higher level than anyone had envisioned the musical style to be capable of. The series of seven polonaises published in his lifetime (another nine were published posthumously), beginning with the Op. 26 pair, set a whole new standard for composing and playing the music and were rooted in a passion by Chopin to write something to celebrate Polish culture — after the country had fallen back into the Russian grip. The A major polonaise Op. 40 No. 1, "Military," and the polonaise in A flat major Op. 53, "Heroic," are among Chopin's most beloved and played works.

Romanticism

Chopin regarded most of his contemporaries with some indifference, although he had many acquaintances with those associated with romanticism in music, literature and the arts, (many of them via his liaison with George Sand). Chopin's music is however considered by many to be a peak of the Romantic style. The relative classical purity and discretion in his music, with little extravagant exhibitionism, partly reflects his reverence of Bach and Mozart. (Chopin based the sequence of his Preludes on the Well-Tempered Clavier of Bach). Chopin also never indulged in explicit 'scene painting' in his music, or used programmatic titles, castigating publishers who renamed his pieces in this way.

Works

All Chopin's works involve the piano, solo or accompanied. They are predominantly for solo piano, but include a small number of piano ensembles with instruments, including a second piano, violin, cello, voice or orchestra.

Over 230 of Chopin's works survive. Various manuscripts and pieces from early childhood have been lost.

Chopin in popular culture

- A statue of Chopin was erected before World War II in Warsaw's Łazienki Park. At its base, in summer, free piano recitals of Chopin's compositions are performed on Sundays. The stylized tree over Chopin's figure echoes a pianist's hand and fingers.

- In commemoration of the genius of Frédéric Chopin, the International Frederick Chopin Piano Competition is held every five years in Warsaw.

- The Grand prix du disque de F.Chopin is awarded periodically for notable Chopin recordings, both remastered and newly-recorded work.

Eponyms

The following have been named after the composer:

- Asteroid 3784 Chopin

- Warsaw Frederic Chopin Airport (also known as Frederic Chopin International Airport)