Family

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Animal & Human Rights; Everyday life

A family consists of a domestic group of people (or a number of domestic groups), typically affiliated by birth or marriage, or by analogous or comparable relationships — including domestic partnership, cohabitation, adoption, surname and (in some cases) ownership (as occurred in the Roman Empire).

In many societies, family ties are only those recognized as such by law or a similar normative system. Although many people (including social scientists) have understood familial relationships in terms of "blood", many anthropologists have argued that one must understand the notion of "blood" metaphorically, and that many societies understand 'family' through other concepts rather than through genetics.

Article 16(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says: "The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State".

The family cross-culturally

According to sociology and anthropology, the family has the primary function of reproducing — biologically, sociologically, or both - society. Thus, one's experience of one's family shifts over time. From the perspective of children, the family functions as a family of orientation: the family serves to locate children socially, and plays a major role in their enculturation and socialization. From the point of view of the parent(s), the family serves as a family of procreation with the goal of producing, enculturating and socializing children.

Producing children, however important, does not exhaust the functions of the family. In societies with a sexual division of labor, marriage (and the resulting relationship between a husband and wife) must precede the formation of an economically productive household. In modern societies marriage entails particular rights and privileges that encourage the formation of new families even when participants have no intention of having children.

Types of family

The structure of families traditionally hinges on relations between parents and children, on relations between spouses, or on both. Anthropologists have called attention to three major types of family:

- matrifocal;

- consanguineal;

- conjugal.

Note: this typology deals with "ideal" families. All societies tolerate some acceptable deviations from the ideal or statistical norm, owing either to incidental circumstances (such as the death of a member of the family), to infertility or to personal preferences.

Matrifocal families

A matrifocal family consists of a mother and her children — generally her biological offspring, although nearly every society also practices adoption of children. This kind of family commonly develops where women have the resources to rear their children by themselves, or where men have more mobility than women. Some indigenous South American and Melanesian societies are matrifocal.

Among polygynous societies studied along the Orinoco river system in southern Venezuela, families are set up in two levels. The larger system consists of one man, one to five women, and their children. The smaller matrifocal family consists of each woman and her children. The children are reared by their mothers as they would in a simple matrifocal system, with most fathers not being closely involved.

Consanguineal families

A consanguineal family comes in various forms, but the most common subset consists of a mother and her children, and other people — usually the family of the mother. This kind of family commonly evolves where mothers do not have the resources to rear their children on their own, fathers are not often present, and especially where property changes ownership through inheritance. When men own important property, consanguineal families commonly consist of a husband and wife, their children, and other members of the husband's family.

Conjugal families

A conjugal family consists of one or more mothers and their children, and/or one or more fathers. This kind of family occurs commonly where a division of labor requires the participation of both men and women, and where families have relatively high mobility. A notable subset of this family type, the nuclear family, has one woman with one husband, and they raise their children. This was formerly known as the " Eskimo system" in anthropology.

Family in the West

The different types of families occur in a wide variety of settings, and their specific functions and meanings depend largely on their relationship to other social institutions. Sociologists have an especial interest in the function and status of these forms in stratified (especially capitalist) societies.

Non-scholars, especially in the United States and Europe, use the term " nuclear family" to refer to conjugal families. Sociologists distinguish between conjugal families (relatively independent of the kindreds of the parents and of other families in general) and nuclear families (which maintain relatively close ties with their kindreds).

Non-scholars, especially in the United States and Europe, also use the term " extended family". This term has two distinct meanings. First, it serves as a synonym of "consanguinal family". Second, in societies dominated by the conjugal family, it refers to kindred (an egocentric network of relatives that extends beyond the domestic group) who do not belong to the conjugal family.

These types refer to ideal or normative structures found in particular societies. Any society will exhibit some variation in the actual composition and conception of families. Much sociological, historical and anthropological research dedicates itself to the understanding of this variation, and of changes in the family form over time. Thus, some speak of the bourgeois family, a family structure arising out of 16th-century and 17th-century European households, in which the family centers on a marriage between a man and woman, with strictly-defined gender-roles. The man typically has responsibility for income and support, the woman for home and family matters.

In contemporary Europe and the United States, people in academic, political and civil sectors have called attention to single-father-headed households, and families headed by same-sex couples, although academics point out that these forms exist in other societies.

Economic function of the family

Anthropologists have often supposed that the family in a traditional society forms the primary economic unit. This economic role has gradually diminished in modern times, and in societies like the United States it has become much smaller — except in certain sectors such as agriculture and in a few upper class families. In China the family as an economic unit still plays a strong role in the countryside. However, the relations between the economic role of the family, its socio-economic mode of production and cultural values remain highly complex.

Families and other social institutions

Wherever people agree that families seem fundamental to the ordered nature of society, other social institutions such as the state and organised religion will make special provisions for families and will support (in word and/or in deed) the idea of the family. This can however lead to problems if conflicting loyalties arise. Thus the Biblical prescription: "every one that hath forsaken houses, or brethren, or sisters, or father, or mother, or wife, or children, or lands, for my name's sake, shall receive a hundredfold, and shall inherit everlasting life" (Matthew 19, 29). Totalitarian states also can develop ambiguous attitudes to families, which they may perceive as potentially interfering with the fostering of official ideology and practice. Different attitudes to divorce and to denunciation may develop in this light.

Families and Political Structure

On the other hand family structures or its internal relationships may affect both state and religious institutions. J.F. del Giorgio in The Oldest Europeans points that the high status of women among the descendants of the post-glacial Paleolithic European population was coherent with the fierce love of freedom of pre-Indo-European tribes. He believes that the extraordinary respect for women in those families made that children raised in such atmosphere tended to distrust strong, authoritarian leaders. According to del Giorgio, European democracies have their roots in those ancient ancestors.

Kinship terminology

Anthropologist Louis Henry Morgan (1818–1881) performed the first survey of kinship terminologies in use around the world. Though much of his work is now considered dated, he argued that kinship terminologies reflect different sets of distinctions. For example, most kinship terminologies distinguish between sexes (the difference between a brother and a sister) and between generations (the difference between a child and a parent). Moreover, he argued, kinship terminologies distinguish between relatives by blood and marriage (although recently some anthropologists have argued that many societies define kinship in terms other than "blood").

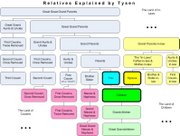

However, Morgan also observed that different languages (and thus, societies) organize these distinctions differently. He thus proposed to describe kin terms and terminologies as either descriptive or classificatory. "Descriptive" terms refer to only one type of relationship, while "classificatory" terms refer to many types of relationships. Most kinship terminologies include both descriptive and classificatory terms. For example, Western societies provide only one way to express relationship with one's brother (brother = parents' son); thus, in Western society, the word "brother" functions as a descriptive term. But many different ways exist to express relationship with one's male first-cousin (cousin = mother's brother's son, mother's sister's son, father's brother's son, father's sister's son, and so on); thus, in Western society, the word "cousin" operates as a classificatory term.

Morgan discovered that a descriptive term in one society can become a classificatory term in another society. For example, in some societies one would refer to many different people as "mother" (the woman who gave birth to oneself, as well as her sister and husband's sister, and also one's father's sister). Moreover, some societies do not lump together relatives that the West classifies together. For example, some languages have no one word equivalent to "cousin", because different terms refer to mother's sister's children and to father's sister's children.

Armed with these different terms, Morgan identified six basic patterns of kinship terminologies:

- Hawaiian: the most classificatory; only distinguishes between sex and generation.

- Sudanese: the most descriptive; no two relatives share the same term.

- Eskimo: has both classificatory and descriptive terms; in addition to sex and generation, also distinguishes between lineal relatives (those related directly by a line of descent) and collateral relatives (those related by blood, but not directly in the line of descent). Lineal relatives have highly descriptive terms, collateral relatives have highly classificatory terms.

- Iroquois: has both classificatory and descriptive terms; in addition to sex and generation, also distinguishes between siblings of opposite sexes in the parental generation. Siblings of the same sex class as blood relatives, but siblings of the opposite sex count as relatives by marriage. Thus, one calls one's mother's sister "mother", and one's father's brother "father"; however, one refers to one's mother's brother as "father-in-law", and to one's father's sister as "mother-in-law".

- Crow: like Iroquois, but further distinguishes between mother's side and father's side. Relatives on the mother's side of the family have more descriptive terms, and relatives on the father's side have more classificatory terms.

- Omaha: like Iroquois, but further distinguishes between mother's side and father's side. Relatives on the mother's side of the family have more classificatory terms, and relatives on the father's side have more descriptive terms.

Western kinship

Most Western societies employ Eskimo kinship terminology. This kinship terminology commonly occurs in societies based on conjugal (or nuclear) families, where nuclear families have a degree of relatively mobility.

Members of the nuclear family use descriptive kinship terms:

- Mother: the female parent

- Father: the male parent

- Son: the males born of the mother; sired by the father

- Daughter: the females born of the mother; sired by the father

- Brother: a male born of the same mother; sired by the same father

- Sister: a female born of the same mother; sired by the same father

Such systems generally assume that the mother's husband has also served as the biological father. In some families, a woman may have children with more than one man or a man may have children with more than one woman. The system refers to a child who shares only one parent with another child as a "half-brother" or "half-sister". For children who do not share biological or adoptive parents in common, English-speakers use the term "step-brother" or "step-sister" to refer to their new relationship with each other when one of their biological parents marries one of the other child's biological parents.

Any person (other than the biological parent of a child) who marries the parent of that child becomes the "step-parent" of the child, either the "stepmother" or "stepfather". The same terms generally apply to children adopted into a family as to children born into the family.

Typically, societies with conjugal families also favour neolocal residence; thus upon marriage a person separates from the nuclear family of their childhood (family of orientation) and forms a new nuclear family (family of procreation). This practice means that members of one's own nuclear family once functioned as members of another nuclear family, or may one day become members of another nuclear family.

Members of the nuclear families of members of one's own (former) nuclear family may class as lineal or as collateral. Kin who regard them as lineal refer to them in terms that build on the terms used within the nuclear family:

- Grandparent

- Grandfather: a parent's father

- Grandmother: a parent's mother

- Grandson: a child's son

- Granddaughter: a child's daughter

For collateral relatives, more classificatory terms come into play, terms that do not build on the terms used within the nuclear family:

- Uncle: father's brother, father's sister's husband, mother's brother, mother's sister's husband

- Aunt: father's sister, father's brother's wife, mother's sister, mother's brother's wife

- Nephew: sister's son, brother's son

- Niece: sister's daughter, brother's daughter

When additional generations intervene (in other words, when one's collateral relatives belong to the same generation as one's grandparents or grandchildren), the prefix "grand" modifies these terms. (Although in casual usage in the USA a "grand aunt" is often referred to as a "great aunt", for instance.) And as with grandparents and grandchildren, as more generations intervene the prefix becomes "great grand", adding an additional "great" for each additional generation.

Most collateral relatives have never had membership of the nuclear family of the members of one's own nuclear family.

- Cousin: the most classificatory term; the children of aunts or uncles. One can further distinguish cousins by degrees of collaterality and by generation. Two persons of the same generation who share a grandparent count as "first cousins" (one degree of collaterality); if they share a great-grandparent they count as "second cousins" (two degrees of collaterality) and so on. If two persons share an ancestor, one as a grandchild and the other as a great-grandchild of that individual, then the two descendants class as "first cousins once removed" (removed by one generation); if the shared ancestor figures as the grandparent of one individual and the great-great-grandparent of the other, the individuals class as "first cousins twice removed" (removed by two generations), and so on. Similarly, if the shared ancestor figures as the great-grandparent of one person and the great-great-grandparent of the other, the individuals class as "second cousins once removed". Hence the phrase "third cousin once removed upwards".

Distant cousins of an older generation (in other words, one's parents' first cousins), though technically first cousins once removed, often get classified with "aunts" and "uncles".

Similarly, a person may refer to close friends of one's parents as "aunt" or "uncle", or may refer to close friends as "brother" or "sister", using the practice of fictive kinship.

English-speakers mark relationships by marriage (except for wife/husband) with the tag "-in-law". The mother and father of one's spouse become one's mother-in-law and father-in-law; the female spouse of one's child becomes one's daughter-in-law and the male spouse of one's child becomes one's son-in-law. The term "sister-in-law" refers to three essentially different relationships, either the wife of one's brother, or the sister of one's spouse, or the wife of one's spouse's sibling. "Brother-in-law" expresses a similar ambiguity. No special terms exist for the rest of one's spouse's family.

The terms "half-brother" and "half-sister" indicate siblings who one share only one biological or adoptive parent.