Computational chemistry

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: General Chemistry

Computational chemistry is a branch of chemistry that uses the results of theoretical chemistry incorporated into efficient computer programs to calculate the structures and properties of molecules and solids, applying these programs to real chemical problems. Examples of such properties are structure (i.e. the expected positions of the constituent atoms), energy and interaction energy, charges, dipoles and higher multipole moments, vibrational frequencies, reactivity or other spectroscopic quantitities, and cross sections for collision with other particles. The term computational chemistry is also sometimes used to cover any of the areas of science that overlap between computer science and chemistry. Electronic configuration theory is the largest subdiscipline of computational chemistry.

Introduction

The term theoretical chemistry may be defined as a mathematical description of chemistry, whereas computational chemistry is usually used when a mathematical method is sufficiently well developed that it can be automated for implementation on a computer. Note that the words exact and perfect do not appear here, as very few aspects of chemistry can be computed exactly. Almost every aspect of chemistry, however, can be described in a qualitative or approximate quantitative computational scheme.

Molecules consist of nuclei and electrons, so the methods of quantum mechanics apply. Computational chemists often attempt to solve the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation, with relativistic corrections added, although some progress has been made in solving the fully relativistic Schrödinger equation. It is, in principle, possible to solve the Schrödinger equation, in either its time-dependent form or time-independent form as appropriate for the problem in hand, but this in practice is not possible except for very small systems. Therefore, a great number of approximate methods strive to achieve the best trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. Present computational chemistry can routinely and very accurately calculate the properties of molecules that contain no more than 10-40 electrons. The treatment of larger molecules that contain a few dozen electrons is computationally tractable by approximate methods such as density functional theory (DFT). There is some dispute within the field whether the latter methods are sufficient to describe complex chemical reactions, such as those in biochemistry. Large molecules can be studied by semi-empirical approximate methods. Even larger molecules are treated with classical mechanics in methods called molecular mechanics.

In theoretical chemistry, chemists, physicists and mathematicians develop algorithms and computer programs to predict atomic and molecular properties and reaction paths for chemical reactions. Computational chemists, in contrast, may simply apply existing computer programs and methodologies to specific chemical questions. There are two different aspects to computational chemistry:

- Computational studies can be carried out in order to find a starting point for a laboratory synthesis, or to assist in understanding experimental data, such as the position and source of spectroscopic peaks.

- Computational studies can be used to predict the possibility of so far entirely unknown molecules or to explore reaction mechanisms that are not readily studied by experimental means.

Thus computational chemistry can assist the experimental chemist or it can challenge the experimental chemist to find entirely new chemical objects.

Several major areas may be distinguished within computational chemistry:

- The prediction of the molecular structure of molecules by the use of the simulation of forces to find stationary points on the energy hypersurface as the position of the nuclei is varied.

- Storing and searching for data on chemical entities (see chemical databases).

- Identifying correlations between chemical structures and properties (see QSPR and QSAR).

- Computational approaches to help in the efficient synthesis of compounds.

- Computational approaches to design molecules that interact in specific ways with other molecules (e.g. drug design).

Molecular structure

A given molecular formula can represent a number of molecular isomers. Each isomer is a local minimum on the energy surface (called the potential energy surface) created from the total energy (electronic energy plus repulsion energy between the nuclei) as a function of the coordinates of all the nuclei. A stationary point is a geometry such that the derivative of the energy with respect to all displacements of the nuclei is zero. A local (energy) minimum is a stationary point where all such displacements lead to an increase in energy. The local minimum that is lowest is called the global minimum and corresponds to the most stable isomer. If there is one particular coordinate change that leads to a decrease in the total energy in both directions, the stationary point is a transition structure and the coordinate is the reaction coordinate. This process of determining stationary points is called geometry optimisation.

The determination of molecular structure by geometry optimisation became routine only when efficient methods for calculating the first derivatives of the energy with respect to all atomic coordinates became available. Evaluation of the related second derivatives allows the prediction of vibrational frequencies if harmonic motion is assumed. In some ways more importantly it allows the characterisation of stationary points. The frequencies are related to the eigenvalues of the matrix of second derivatives (the Hessian matrix). If the eigenvalues are all positive, then the frequencies are all real and the stationary point is a local minimum. If one eigenvalue is negative (an imaginary frequency), the stationary point is a transition structure. If more than one eigenvalue is negative the stationary point is a more complex one, and usually of little interest. When found, it is necessary to move the search away from it, if we are looking for local minima and transition structures.

The total energy is determined by approximate solutions of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, usually with no relativistic terms included, and making use of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation which, based on the much higher velocity of the electrons in comparison with the nuclei, allows the separation of electronic and nuclear motions, and simplifies the Schrödinger equation. This leads to evaluating the total energy as a sum of the electronic energy at fixed nuclei positions plus the repulsion energy of the nuclei. A notable exception are certain approaches called direct quantum chemistry, which treat electrons and nuclei on a common footing. Density functional methods and semi-empirical methods are variants on the major theme. For very large systems the total energy is determined using molecular mechanics. The ways of determing the total energy to predict molecular structures are:-

Ab initio methods

The programs used in computational chemistry are based on many different quantum-chemical methods that solve the molecular Schrödinger equation associated with the molecular Hamiltonian. Methods that do not include any empirical or semi-empirical parameters in their equations - being derived directly from theoretical principles, with no inclusion of experimental data - are called ab initio methods. This does not imply that the solution is an exact one; they are all approximate quantum mechanical calculations. It means that a particular approximation is rigorously defined on first principles (quantum theory) and then solved within an error margin that is qualitatively known beforehand. If numerical iterative methods have to be employed, the aim is to iterate until full machine accuracy is obtained (the best that is possible with a finite word length on the computer, and whithin the mathematical and/or physical approximations made).

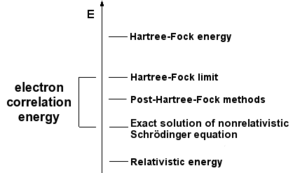

The simplest type of ab initio electronic structure calculation is the Hartree-Fock (HF) scheme, in which the Coulombic electron-electron repulsion is not specifically taken into account. Only its average effect is included in the calculation. As the basis set size is increased the energy and wave function tend to a limit called the Hartree-Fock limit. Many types of calculations, known as post-Hartree-Fock methods, begin with a Hartree-Fock calculation and subsequently correct for electron-electron repulsion, referred to also as electronic correlation. As these methods are pushed to the limit, they approach the exact solution of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation. In order to obtain exact agreement with experiment, it is necessary to include relativistic and spin orbit terms, both of which are only really important for heavy atoms. In all of these approaches, in addition to the choice of method, it is necessary to chose a basis set. This is set of functions, usually centred on the different atoms in the molecule, which are used to expand the molecular orbitals with the LCAO ansatz. Ab initio methods need to define a level of theory (the method) and a basis set.

The Hartree-Fock wave function is a single configuration or determinant. In some cases, particularly for bond breaking processes, this is quite inadequate and several configurations need to be used. Here the coefficients of the configurations and the coefficients of the basis functions are optimised together.

The total molecular energy can be evaluated as a function of the molecular geometry, in other words the potential energy surface.

Example: Is Si2H2 like acetylene (C2H2)?

A series of ab initio studies of Si2H2 shows clearly the power of ab initio computational chemistry. They go back over 20 years, and most of the main conclusions were reached by 1995. The methods used were mostly post-Hartree-Fock, particularly Configuration interaction (CI) and Coupled cluster (CC). Initially the question was whether Si2H2 had the same structure as ethyne (acetylene), C2H2. Slowly (because this started before geometry optimization was widespread), it became clear that linear Si2H2 was a transition structure between two equivalent trans-bent structures and that it was rather high in energy. The ground state was predicted to be a four-membered ring bent into a 'butterfly' structure with hydrogen atoms bridged between the two silicon atoms. Interest then moved to look at whether structures equivalent to vinylidene - Si=SiH2 - existed. This structure is predicted to be a local minimum, i. e. an isomer of Si2H2, lying higher in energy than the ground state but below the energy of the trans-bent isomer. Then surprisingly a new isomer was predicted by Brenda Colegrove in Henry F. Schaefer, III's group. This prediction was so surprising that it needed extensive calculations to confirm it. It requires post Hartree-Fock methods to obtain a local minimum for this structure. It does not exist on the Hartree-Fock energy hypersurface. The new isomer is a planar structure with one bridging hydrogen atom and one terminal hydrogen atom, cis to the bridging atom. Its energy is above the ground state but below that of the other isomers. Similar results were later obtained for Ge2H2 and SiGeH2 . More interestingly, similar results were obtained for Al2H2 (and then Ga2H2 and AlGaH2) which have two electrons less than the Group 14 molecules. The only difference is that the four-membered ring ground state is planar and not bent. The cis-mono-bridged and vinylidene-like isomers are present. Experimental work on these molecules is not easy, but matrix isolation spectroscopy of the products of the reaction of hydrogen atoms and silicon and aluminium surfaces has found the ground state ring structures and the cis-mono-bridged structures for Si2H2 and Al2H2. Theoretical predictions of the vibrational frequencies were crucial in understanding the experimental observations of the spectra of a mixture of compounds. This may appear to be an obscure area of chemistry, but the differences between carbon and silicon chemistry is always a lively question, as are the differences between group 13 and group 14 (mainly the B and C differences). The silicon and germanium compounds were the subject of a Journal of Chemical Education article.

Density Functional methods

Density functional theory (DFT) methods are often considered to be ab initio methods for determining the molecular electronic structure, even though many of the most common functionals use parameters derived from empirical data, or from more complex calculations. This means that they could also be called semi-empirical methods. It is best to treat them as a class on their own. In DFT, the total energy is expressed in terms of the total electron density rather than the wave function. In this type of calculation, there is an approximate Hamiltonian and an approximate expression for the total electron density. DFT methods can be very accurate for little computational cost. The drawback is, that unlike ab initio methods, there is no systematic way to improve the methods by improving the form of the functional.

Semi-empirical and empirical methods

Semi-empirical quantum chemistry methods are based on the Hartree-Fock formalism, but make many approximations and obtain some parameters from empirical data. They are very important in computational chemistry for treating large molecules where the full Hartree-Fock method without the approximations is too expensive. The use of empirical parameters appears to allow some inclusion of correlation effects into the methods.

Semi-empirical methods follow what are often called empirical methods where the two-electron part of the Hamiltonian is not explicitly included. For π-electron systems, this was the Hückel method proposed by Erich Hückel, and for all valence electron systems, the Extended Hückel method proposed by Roald Hoffmann.

Molecular mechanics

In many cases, large molecular systems can be modelled successfully while avoiding quantum mechanical calculations entirely. Molecular mechanics simulations, for example, use a single classical expression for the energy of a compound, for instance the harmonic oscillator. All constants appearing in the equations must be obtained beforehand from experimental data or ab initio calculations.

The database of compounds used for parameterization - (the resulting set of parameters and functions is called the force field) - is crucial to the success of molecular mechanics calculations. A force field parameterized against a specific class of molecules, for instance proteins, would be expected to only have any relevance when describing other molecules of the same class.

Interpreting molecular wave functions

The Atoms in Molecules model developed by Richard Bader was developed in order to effectively link the quantum mechanical picture of a molecule, as an electronic wavefunction, to chemically useful older models such as the theory of Lewis pairs and the valence bond model. Bader has demonstrated that these empirically useful models are connected with the topology of the quantum charge density. This method improves on the use of Mulliken charges.

Computational chemical methods in solid state physics

Computational chemical methods can be applied to solid state physics problems. The electronic structure of a crystal is in general described by a band structure, which defines the energies of electron orbitals for each point in the Brillouin zone. Ab initio and semi-empirical calculations yield orbital energies, therefore they can be applied to band structure calculations. Since it is time-consuming to calculate the energy for a molecule, it is even more time-consuming to calculate them for the entire list of points in the Brillouin zone.

Chemical dynamics

Once the electronic and nuclear variables are separated (within the Born-Oppenheimer representation), in the time-dependent approach, the wave packet corresponding to the nuclear degrees of freedom is propagated via the time evolution operator (physics) associated to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (for the full molecular Hamiltonian). In the complementary energy-dependent approach, the time-independent Schrödinger equation is solved using the scattering theory formalism. The potential respresenting the interatomic interaction is given by the potential energy surfaces. In general, the potential energy surfaces are coupled via the vibronic coupling terms.

The most popular methods for propagating the wave packet associated to the molecular geometry are

- the split operator technique,

- the Multi-Configuration Time-Dependent Hartree method (MCTDH),

- the semiclassical method.

Molecular dynamics (MD) examines (using Newton's laws of motion) the time-dependent behaviour of systems, including vibrations or Brownian motion, using a classical mechanical description. MD combined with density functional theory leads to the Car-Parrinello method.

Software packages

A number of self-sufficient software packages include many quantum-chemical methods, and in some cases molecular mechanics methods. The following table illustrates the capabilities of the most versatile software packages that show an entry in two or more columns of the table. There are separate lists for specialized programs, such as:-

- Density functional theory programs

- Semi-empirical programs

- Solid state system programs with periodic boundary conditions.

- Valence Bond programs

| Package | Molecular Mechanics | Semi-Empirical | Hartree-Fock | Post-Hartree-Fock methods | Density Functional Theory |

| ACES | N | N | Y | Y | N |

| CADPAC | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| COLUMBUS | N | N | Y | Y | N |

| DALTON | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| GAUSSIAN | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| GAMESS (UK) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| GAMESS (US) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| JAGUAR | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| MOLCAS | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| MOLPRO | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| MPQC | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| NWChem | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| PLATO | Y | N | N | N | Y |

| PQS | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| PSI | N | N | Y | Y | N |

| TURBOMOLE | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Q-Chem | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |