Book

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Literature types

| Literature |

|---|

|

| Major forms |

| Epic • Romance • Novel |

| Media |

| Performance • Book |

| Techniques |

| Prose • Poetry |

| History & lists |

| History • Modern History • Books • Authors • Awards • Basic Topics |

| Discussion |

| Criticism • Theory • Magazines |

A book is a collection of paper, parchment or other material with a piece of text written on them, bound together along one edge, usually within covers. Each side of a sheet is called a page and a single sheet within a book may be called a leaf. A book is also a literary work or a main division of such a work. A book produced in electronic format is known as an e-book.

In library and information science, a book is called a monograph to distinguish it from serial publications such as magazines, journals or newspapers.

Publishers may produce low-cost, pre-publication copies known as galleys or 'bound proofs' for promotional purposes, such as generating reviews in advance of publication. Galleys are usually made as cheaply as possible, since they are not intended for sale.

A lover of books is usually referred to as a bibliophile, a bibliophilist, or a philobiblist, or, more informally, a bookworm.

A book may be studied by students in the form of a book report. It may also be covered by a professional writer as a book review to introduce a new book. Some belong to a book club.

History of books

Antiquity

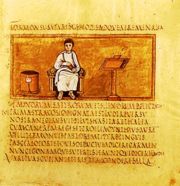

The oral account ( word of mouth, tradition, hearsay) is the oldest carrier of messages and stories. When writing systems were invented in ancient civilizations, nearly everything that could be written upon—stone, clay, tree bark, metal sheets—was used for writing. Alphabetic writing emerged in Egypt around 1800 BC and at first the words were not separated from each other (scripta continua) and there was no punctuation. The text could be written from right to left, from left to right or even so that alternate lines must be read in opposite directions ( boustrophedon).

Scroll

In Ancient Egypt, papyrus (a form of paper made from the stems of the papyrus plant) was used for writing maybe as early as from First Dynasty, but first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC). Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a scroll. This custom gained widespread popularity in the Hellenistic and Roman world, although we have evidence that tree bark (Latin liber, from there also library) and other materials were also used. According to Herodotus (History 5:58) the Phoenicians brought writing and also papyrus to Greece around tenth or ninth century BC and so the Greek word for papyrus as writing material (biblion) and book (biblos) come from the Phoenician port town Byblos through which most of the papyrus was exported to Greece.

Codex

In schools, in accounting and for taking notes wax tablets were the normal writing material. Wax tablets had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted and a new text carved into the wax. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex). Also the etymology of the word codex (block of wood) suggest that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.

As witnessed by the findings in Pompeii papyrus scrolls were still dominant in the first century AD. At the end of the century we have the first written mention of the codex as a form of book from Martial in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV, where he praises its compactness. In the pagan Hellenistic world however, the codex never gained much popularity and only within the Christian community was it popularized and gained widespread use. This gradual change happened during the third and fourth centuries and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book are several: the codex format is more economical as both sides of the writing material can be used, it is easy to conceal, portable and searchable. It is also possible that the Christian authors distinguished their writings on purpose from the pagan texts which were written normally in the form of scrolls.

In the 7th century Isidore of Seville explains the relation between codex, book and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13) as this:

- A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches.

Middle Ages

Manuscripts

The fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D. saw the decline of the culture of ancient Rome. Due to lack of contacts with Egypt the papyrus became difficult to obtain and parchment (what had been used for writing already for centuries) started to be the main writing material.

In Western Roman Empire mainly monasteries carried on the latin writing tradition, because first Cassiodorus in the monastery of Vivarium (established around 540) stressed the importance of copying texts, and later also St. Benedict of Nursia, in his Regula Monachorum (completed around the middle of the 6th century) promoted reading. The Rule of St. Benedict (Ch. XLVIII), which set aside certain times for reading, greatly influenced the monastic culture of the Middle Ages, and is one of the reasons why the clergy were the predominant readers of books. At first the tradition and style of the Roman Empire still dominated and only slowly the peculiar medieval book culture emerged.

Before the invention and adoption of the printing press, almost all books were copied by hand, which made books expensive and comparatively rare. Smaller monasteries had usually only some dozen books, medium sized a couple hundred. By the ninth century larger collections held around 500 volumes and even at the end of the Middle Ages the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of Sorbonne held only around 2000 volumes.

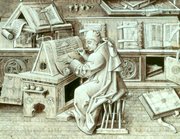

The scriptorium of the monastery was usually located over the chapter house and artificial light was forbidden in fear that it may damage the manuscripts. The bookmaking process was long and laborious. At first the parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after that the text was written by the scribe who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Only after that the book was bound by the bookbinder.

There were four types of scribes:

- Copyists, who dealt with basic production and correspondence

- Calligraphers, who dealt in fine book production

- Correctors, who collated and compared a finished book with the manuscript from which it had been produced

- Rubricators, who painted in the red letters; and Illuminators, who painted illustrations

Already in antiquity there were known different types of ink, usually prepared from soot and gum or later also from gall nuts and iron vitriol. This gave writing the typical brownish black colour, but black or brown were not the only colours used. There are texts written in red or even gold, and of course different colours were used for illumination. Sometimes the whole parchment was coloured purple and the text was written on it with gold or silver (eg Codex Argenteus). Irish monks introduced spacing between words in the seventh century. This facilitated reading, as these monks tended to be less familiar with Latin. However the use of spaces between words did not become commonplace before 12th century. It has been argued, that the use of spacing between words shows the transition from semi-vocalized reading into silent reading.

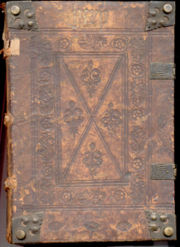

The first books used parchment or vellum (calf skin) for the pages. The book covers were made of wood and covered with leather. As dried parchment tends to assume the form before processing, the books were fitted with clasps or straps. During later Middle Ages, when public libraries appeared, books were often chained to a bookshelf or a desk to prevent theft. The so called libri catenati were used up to 18th century.

At first books were copied mostly in monasteries, one at a time. With the rise of universities in the 13th century, the demand for books increased and a new system for copying books appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the book production speed was considerably increased. The system was maintained by stationers guilds, which were secular, and produced both religious and non-religious material.

Block printing and incunables

In block printing, a relief image of an entire page was carved out of blocks of wood. It could then be inked and used to reproduce many copies of that page. This method was used widely throughout East Asia, originating in Eygpt and China sometime between the mid-6th and late 9th centuries as a method of printing on paper and cloth. The oldest dated (868 AD) book printed with this method is The Diamond Sutra.

This method (called also xylography) arrived to Europe in the early 14th century. Books, as well as playing cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by such method. Creating an entire book, however, was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page. Also, the wood blocks were not durable and could easily wear out or crack.

The Chinese inventor Pi Sheng made movable type of earthenware circa 1045, but we have no surviving examples of his printing. Metal movable type was invented in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (around 1230), but was not widely used, one reason being the enormous Chinese character set. Around 1450, in what is commonly regarded as an independent invention, Johannes Gutenberg introduced movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention made books comparatively affordable (although still quite expensive for most people) and more widely available. It is estimated that in Europe about 1,000 various books were created per year before the development of the printing press. These early printed books, single sheets and images which are created before the year 1501 in Europe are known as incunabula, sometimes anglicized to incunables.

Paper

Though papermaking in Europe begun around 11th century, up until the beginning of 16th century vellum and paper were produced congruent to one another, vellum being the more expensive and durable option. Printers or publishers would often issue the same publication on both materials, to cater to more than one market. As was the case with many medieval inventions, paper was first made in China, as early as 200 B.C., and reached Europe through muslim territories. At first made of rags, the industrial revolution changed paper-making practices, allowing for paper to be made out of wood pulp.

Modern world

With the rise of printing in the fifteenth century, books were published in limited numbers and were quite valuable. The need to protect these precious commodities was evident. One of the earliest references to the use of bookmarks was in 1584 when the Queen's Printer, Christopher Barker, presented Queen Elizabeth I with a fringed silk bookmark. Common bookmarks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were narrow silk ribbons bound into the book at the top of the spine and extended below the lower edge of the page. The first detachable bookmarks began appearing in the 1850's and were made from silk or embroidered fabrics. Not until the 1880's, did paper and other materials become more common.

Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 1800s. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour, but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour.

Monotype and linotype presses were introduced in the late 19th century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once.

The centuries after the 15th century were thus spent on improving both the printing press and the conditions for freedom of the press through the gradual relaxation of restrictive censorship laws. See also intellectual property, public domain, copyright. In mid-20th century, Europe book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year.

Structure of books

Depending on a book's purpose or type (e.g. Encyclopedia, Dictionary, Textbook, Monograph), its structure varies, but some common structural parts of a book usually are:

- Book cover (hard or soft, shows title and author of book, sometimes with illustration)

- Title page (shows title and author, often with small illustration or icon)

- Metrics page

- Dedication (may or may not be included)

- Table of contents

- Preface

- Text of contents of the book

- Index

Conservation issues

In the early-19th century, papers made from pulp (cellulose, wood) were introduced because it was cheaper than cloth-based papers ( linen or abaca). Pulp based paper made cheap novels, cheap school text books and cheap books of all kinds available to the general public. This paved the way for huge leaps in the rate of literacy in industrialised nations and eased the spread of information during the Second Industrial Revolution.

However, this pulp paper contained acid that causes a sort of slow fires that eventually destroys the paper from within. Earlier techniques for making paper used limestone rollers which neutralized the acid in the pulp. Libraries today have to consider mass deacidification of their older collections. Books printed between 1850 and 1950 are at risk; more recent books are often printed on acid-free or alkaline paper.

The proper care of books takes into account the possibility of chemical changes to the cover and text. Books are best stored in reduced lighting, definitely out of direct sunlight, at cool temperatures, and at moderate humidity. Books, especially heavy ones, need the support of surrounding volumes to maintain their shape. It is desirable for that reason to group books by size.

Collections of books

Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books, (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) first appeared in classical Greece. In ancient world the maintaining of a library was usually (but not exclusively) the privilege of a wealthy individual. These libraries could have been either private or public, i.e. for individuals that were interested in using them. The difference from a modern public library lies in the fact that they were usually not funded from public sources. It is estimated that in the city of Rome at the end of the third century there were around 30 public libraries, public libraries also existed in other cities of the ancient Mediterranean region (e.g. Library of Alexandria). Later, in the Middle Ages, monasteries and universities had also libraries that could be accessible to general public. Typically not the whole collection was available to public, the books could not be borrowed and often were chained to reading stands to prevent theft.

The beginning of modern public library begins around 15th century when individuals started to donate books to towns. The growth of a public library system in the United States started in the late 19th century and was much helped by donations from Andrew Carnegie. This reflected classes in a society: The poor or the middle class had to access most books through a public library or by other means while the rich could afford to have a private library built in their homes.

The advent of paperback books in the 20th century led to an explosion of popular publishing. Paperback books made owning books affordable for many people. Paperback books often included works from genres that had previously been published mostly in pulp magazines. As a result of the low cost of such books and the spread of bookstores filled with them (in addition to the creation of a smaller market of extremely cheap used paperbacks) owning a private library ceased to be a status symbol for the rich.

While a small collection of books, or one to be used by a small number of people, can be stored in any way convenient to the owners, including a standard bookcase, a large or public collection requires a catalogue and some means of consulting it. Often codes or other marks have to be added to the books to speed the process of relating them to the catalogue and their correct shelf position. Where these identify a volume uniquely, they are referred to as "call numbers". In large libraries this call number is usually based on a Library classification system. The call number is placed inside the book and on the spine of the book, normally a short distance before the bottom, in accordance with institutional or national standards such as ANSI/ NISO Z39.41 - 1997. This short (7 pages) standard also establishes the correct way to place information (such as the title or the name of the author) on book spines and on "shelvable" book-like objects such as containers for DVDs, video tapes and software.

In library and booksellers' catalogues, it is common to include an abbreviation such as "Crown 8vo" to indicate the paper size from which the book is made.

When rows of books are lined on a bookshelf, bookends are sometimes needed to keep them from slanting.

Keeping track of books

One of the earliest and most widely known systems of cataloguing books is the Dewey Decimal System. This system has fallen out of use in some places, mainly because of a Eurocentric bias and other difficulties applying the system to modern libraries. However, it is still used by most public libraries in America. Another popular classification system is the Library of Congress system, which is more popular in university libraries.

For the entire 20th century most librarians concerned with offering proper library services to the public (or a smaller subset such as students) worried about keeping track of the books being added yearly to the Gutenberg Galaxy. Through a global society called the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions ( IFLA) they devised a series of tools such as the International Standard Book Description or ISBD.

Besides, each book is specified by an International Standard Book Number, or ISBN, which is unique to every edition of every book produced by participating publishers, world wide. It is managed by the ISBN Society. It has four parts. The first part is the country code, the second the publisher code, and the third the title code. The last part is a checksum or a check digit and can take values from 0–9 and X (10). The EAN Barcodes numbers for books are derived from the ISBN by prefixing 978, for Bookland and calculating a new check digit.

Many government publishers, in industrial countries as well as in developing countries, do not participate fully in the ISBN system. They often produce books which do not have ISBNs. In certain industrialized countries large classes of commercial books, such as novels, textbooks and other non-fiction books, are nearly always given ISBNs by publishers, thus giving the illusion to many customers that the ISBN is an international and complete system, with no exceptions.

Transition to digital format

The term e-book (electronic book) in the broad sense is an amount of information like a conventional book, but in digital form. It is made available through internet, CD-ROM, etc. In the popular press the term e-Book sometimes refers to a device such as the Sony Librie EBR-1000EP, which is meant to read the digital form and present it in a human readable form.

Throughout the 20th century, libraries have faced an ever-increasing rate of publishing, sometimes called an information explosion. The advent of electronic publishing and the Internet means that much new information is not printed in paper books, but is made available online through a digital library, on CD-ROM, or in the form of e-books.

On the other hand, though books are nowadays produced using a digital version of the content, for most books such a version is not available to the public (i.e. neither in the library nor on the Internet), and there is no decline in the rate of paper publishing. There is an effort, however, to convert books that are in the public domain into a digital medium for unlimited redistribution and infinite availability. The effort is spearheaded by Project Gutenberg combined with Distributed Proofreaders.

There have also been new developments in the process of publishing books. Technologies such as print on demand have made it easier for less known authors to make their work available to a larger audience.