Bongo (antelope)

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mammals

| iBongo | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Tragelaphus eurycerus Ogilby, 1837 |

The Bongo, Tragelaphus eurycerus, is a large African forest antelope species. It is characterized by a striking reddish coat, black and white markings, prominent colours and long slightly spiral horns.

Taxonomy

The Bongo belongs to the genus Tragelaphus, which includes the Sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekeii), the Nyala (Tragelaphus angasii), the Bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), the Mountain Nyala (Tragelaphus buxtoni), the Lesser Kudu (Tragelaphus imberbis) and the Greater Kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros).

A Bongo is further catalogued into one of the two subspecies: Tragelaphus eurycerus eurycerus, the lowland or "Western Bongo" and the far more rare Tragelaphus eurycerus isaaci, the mountain or "Eastern Bongo" isolated to North-Eastern Central Africa. There are two other subspecies from West and Central Africa, taxonomic clarification not withstanding. Their life span up to 19 years in observation.

The scientific name of the Bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus) is acquired from Greek words. "Tragelaphus" is derived from the Greek words "Trago" (a he-goat), and "elaphos" (a deer), in combination referring to "an antelope". The word "Eurycerus" is originated from the fusion of "eurus" (broad, widespread) and "keras" (an animal's horn). Bongo is an African native name.

Bongos are one of the largest of the forest antelopes, and are considered by many to be the most beautiful of all antelopes. In addition to the deep chestnut colour of their coats, bongos have bright white stripes on their sides to help camouflage them from their enemies.

Gestation is approximately 285 days (9.5 months) with 1 young per birth with weaning at 6 months. Sexual maturity is at 24 to 27 months. Adults of both genders are similar in size. Adult height is about 1.1 to 1.3 m (3' 8"-4' 3") and length is 1.7 to 2.5 m (5' 8"-8' 3"). Females weigh around 210 to 235 kg (460 to 520 lb) while males weigh around 240 to 405 kg (530 to 895 lb). Both sexes have heavy spiraling horns; those of the male are longer and more massive. All bongos in captivity are from the isolated Aberdere Mountain portion of the species’ range in central Kenya.

Physical characteristics and information

Distribution

Bongos are found in dense tropical jungles with dense undergrowth up to an altitude of 4,000 m (12,800 ft) in central Africa, with isolated populations in Kenya, and western Africa. Countries: Angola, Benin [regionally extinct?], Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana. Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya (the only place where the Eastern Bongo are found in the wild), Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Togo [regionally extinct?] and Uganda [regionally extinct] (IUCN, 2002).

Habitat

Historically bongos were found in three disjunct parts of Africa. Evolved for a life in dense forest, jungle and bamboo thickets, one population, the eastern/mountain bongo, is native to the Aberdere Mountains of central Kenya (from which all zoo-held bongos originate). The second is from Central Africa and the third is from West Africa. Today all three populations’ ranges have shrunk in size due to habitat loss for agriculture and uncontrolled timber cutting as well as poaching for meat.

Coat and body

The bongo has the most beautiful and dazzling coat of all antelopes. Its rich and brilliant body sports a bright auburn colour, but the neck, chest and legs are generally darker than the rest of the body. Coats of male bongos become darker and buffy as they age until it results in a dark mahogany-brown colour. Coats of female bongos are usually more brightly coloured than males'. The pigmentation in the coat rubs off quite easily with anecdotal reports that rain running off a bongo has been noticed to run red with pigment.

A bongo's smooth coat is accented with an average of ten to fifteen vertical and white-yellow torso stripes that run from the base of the neck down to the rump. The narrow stripes travel down the sides of the bongo, but the number of stripes on each side is rarely the same. The bongo has a short, bristly and vertical brown ridge of hair with slender white stripes that extends along the shoulder to the rump.

A white chevron appears between the eyes and two large white spots grace each cheek.

The large ears are believed to sharpen hearing, and the distinctive coloration may help bongos identify one another in their dark forest habitats. Bongos have no special secretion glands and so rely less on scent to find one another than do other similar antelopes.

The lips of a bongo are white, topped with a black muzzle.

Horns

Bongos have two heavy and slightly spiralled horns that slope over their back and like in many other antelope species, both the male and female bongos have horns. Bongos are the only Tragelaphid in which both sexes have horns. The horns of bongos are in the form of a lyre and bear a resemblance to those of the related antelope species of nyalas, sitatungas, bushbucks, kudus and elands.

Unlike deer, which have branched antlers that they shed annually, bongos and other antelopes have pointed horns that they keep throughout their lifespan. Males have massive backswept horns while females have smaller, thinner and more parallel horns. The size of the horns range between 75 and 99 centimetres (30 to 39 in). The horns twist once. Like all other horns of antelopes, the core of a bongo's horn is hollow and the outer layer of the horn is made of keratin, the same material that makes up human fingernails, toenails and hair. The Bongo runs gracefully, and at full speed through even the thickest tangles of lianas, laying its heavy spiraled horns on its back so that the brush cannot impede its flight. Bongos are hunted for their horns by humans.

Social organization and behaviour

Like other forest ungulates, bongos are seldom seen in large groups. Males tend to be solitary and groups of females with young seem to live in groups of 6 to 8. Bongos have seldom been seen in herds of more than 20. The preferred habitat of this species is so dense and difficult to operate in that few Europeans or Americans observed this species until the 1960’s. Current living animals derive solely from Kenyan importations made during the period 1969-1978.

As young males mature, they leave their maternal groups. Adult males of similar size or age seem to try to avoid one another, but occasionally they will meet and spar with their horns in a ritualized manner. Sometimes serious fights will take place, but they are usually discouraged by visual displays, in which the males bulge their necks, roll their eyes and hold their horns in a vertical position while slowly pacing back and forth in front of the other male. Younger mature males most often remain solitary, although they sometimes join up with an older male. They seek out females only at mating time; when they are with a herd of females, males do not coerce them or try to restrict their movements as do some other antelopes.

Although bongos are mostly nocturnal, they are occasionally active during the day. They are timid and easily frightened. They will move away after a scare, running at considerable speed, even through dense undergrowth. They seek cover, where they stand very still and alert, facing away from the disturbance and turning their heads from time to time to check on the situation. The bongo's hindquarters are less conspicuous than the forequarters, and from this position the animal can quickly flee.

When in distress the bongo emits a bleat. It uses a limited number of vocalizations, mostly grunts and snorts. The females have a weak, mooing contact call for their young.

Females prefer to use traditional calving grounds restricted to certain areas. The newborn calf lies out in hiding for a week or more, receiving short visits by the mother to suckle it. The calves grow rapidly and can soon accompany their mothers in the nursery herds. Their horns also grow rapidly and begin to show in 3 1/2 months.

Diet

Bongos are herbivorous, like many other forest ungulates. A large animal, the Bongo requires an ample amount of food, and is therefore quite restricted to suitable areas with abundant year-round growth of herbs and low shrubs. Such restrictions may account for the animal's limited distribution.

Bongos are browsers and feed primarily on the leaves of trees, bushes, vines, bark and pith of rotting trees, grasses, herbs, roots, cereals, shrubs and fruits. Bongos need salt in their diet. Indeed, bongos are known to regularly visit natural salt licks. They have been known to eat burned wood after lightning storms; this behaviour is believed to be a means of getting salts and minerals into their diet (See Animal Diversity link 2). Suitable habitat must have permanent water available.

Threats to survival

Population

Few estimates of population density are available. Assuming average population densities of 0.25 animals per km² in regions where it is known to be common or abundant, and 0.02 per km² elsewhere, and with a total area of occupancy of 327,000 km², a total population estimate of approximately 28,000 is suggested. Only about 60% are in protected areas, suggesting that actual numbers of the lowland subspecies may only be in the low tens of thousands. In Kenya, their numbers have declined significantly and on Mt. Kenya, they were extirpated within the last decade due to illegal hunting with dogs. Although information on their status in the wild is lacking, lowland bongos are not presently considered endangered.

Bongos are susceptible to disease such as rinderpest (in the 1890s this disease almost exterminated the species). It has been observed that the Tragelaphus eurycerus may suffer from Goiter (C. A. Schiller et al, Department of Pathology, National Zoological Park, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA. Veterinary Pathology, Vol 32, Issue 3 242-249). Over the course of the disease, the thyroid glands greatly enlarge (up to 10 x 20 cm) and became polycystic. C. A. Schiller et al (cited above) concluded that the pathogenesis of goiter in the Bongo may reflect a mixture of genetic predisposition coupled with environmental factors, including a period of exposure to a goitrogen.

Leopards, Spotted Hyenas, Lions, and Humans prey on them for their pelts, horns and meat; Pythons sometimes eat bongo calves.

Bongo populations have been greatly reduced by hunting and snares, although some bongo refuges exist. Although Bongos are quite easy for humans to catch via snares; it is of interest that many people native to the Bongos habitat believed that if they ate or touched Bongo they would have spasms similar to epileptic seizures. Because of this superstition Bongos were less harmed in their native ranges than expected. However, these taboos are said no longer to exist and that may account for increased hunting by humans in recent times.

Zoo programs

An international studbook is maintained to help manage animals held in captivity. Because of its bright colour, it is very popular in zoos and private collections. In North America, there are thought to be over 400 individuals, a population that probably exceeds that of the mountain bongo in the wild.

In 2000, the American Zoo and Aquarum Association ( AZA) upgraded the Bongo to a Species Survival Plan (SSP) Participant - which works to improve the genetic diversity of managed animal populations. The target population for participating zoos and private collections in North America is 250 animals. Through the efforts of zoos in North America, a reintroduction to the population in Kenya is being developed.

Conservation

The western/lowland Bongo faces an ongoing population decline as habitat destruction and meat hunting pressures increase with the relentless expansion of human settlement. Its long-term survival will only be assured in areas which receive active protection and management. At present, such areas comprise about 30,000 km²., and several are in countries where political stability is fragile. There is therefore a realistic possibility that its status could decline to Threatened in the near future.

As the largest and most spectacular forest antelope, the western/lowland Bongo is both an important flagship species for protected areas such as national parks, and a major trophy species which has been taken in increasing numbers in Central Africa by sport hunters during the 1990’s. Both of these factors are strong incentives to provide effective protection and management of western/lowland bongo populations. Trophy hunting has the potential to provide economic justification for the preservation of larger areas of bongo habitat than national parks, especially in remote regions of Central Africa where possibilities for commercially successful tourism are very limited (Wilkie and Carpenter 1999).

The eastern/mountain Bongo’s survival in the wild is dependent on more effective protection of the surviving remnant populations in Kenya. If this does not occur, if will eventually become extinct in the wild. The existence of a healthy captive population of this subspecies offers the potential for its reintroduction. The total number of mountain Bongos held in captivity in North America alone may already be similar to or exceed the total number remaining in the wild.

Legal status

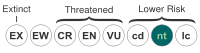

In 2002 the IUCN, listed the species as "low risk/near threatened". This may mean that Bongos may be endangered due to human environmental interaction as well as hunting and illegal actions towards wildlife. Bongos are becoming extinct and endangered due to hunters.

CITES lists bongo as an Appendix III species, only regulating their exportation from a single country, Ghana. It is not protected by the U.S. Endangered Species Act and is not listed by USFWS.

The IUCN Antelope Specialist Group considers the western or lowland bongo, T. e. eurycerus, to be Lower Risk (Near Threatened), and the eastern or mountain bongo, T. e. isaaci, of Kenya to be Endangered. Other subspecific names have been used but their validity has not been tested.