Bay Area Rapid Transit

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Railway transport

|

|

| Locale | San Francisco Bay Area |

|---|---|

| Transit type | Rapid transit |

| Began operation | September 11, 1972 |

| System length | 104 mi (167 km) |

| No. of lines | 5 |

| No. of stations | 43 |

| Daily ridership | 310,717 (avg. weekday exits, FY2005) |

| Track gauge | 5 ft 6 in (1676 mm) |

| Operator | San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District |

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) is a public rapid-transit system that serves parts of the San Francisco Bay Area, including the cities of San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Daly City, Richmond, Fremont, Hayward, Walnut Creek, and Concord. It also serves San Francisco International Airport and, via AirBART buses, Oakland International Airport. The BART acronym is pronounced as a single word, not as individual letters.

BART today

System details

BART comprises 104 miles (167 km) of track and 43 stations. The system uses a 5 ft 6 in (1676 mm) broad rail gauge, as opposed to the 4 ft 8.5 in (1435 mm) standard gauge predominantly found in the U.S. The broad gauge was selected to provide greater stability (due in part to a planned Golden Gate Bridge route), a smoother ride for lightweight aluminum and fibreglass cars, and for political and economic reasons.

Some critics point out that the broad gauge has very little technical merit, but does act as a very effective barrier to use for any other rail system, freight or passenger. The French, German, and Japanese high-speed rail networks, for instance, are all standard gauge, and operate at higher speeds. Most, if not all, light rail systems operate with lightweight cars on standard gauge track. Broad gauge makes engineering more difficult, as track building equipment must be custom-built. In addition, the non-standard gauge makes new fleet procurement extremely expensive because the trains must be custom-built instead of using common designs for standard gauge.

Trains can achieve a centrally-controlled maximum speed of 80 mph (129 km/h) and provide a systemwide average speed of 33 mph (53 km/h) with 20-second station dwell times. Trains operate at a minimum length of three cars per California Public Utilities Commission guidelines to a maximum length of 10 cars, spanning the entire 700 ft (213.3 m) length of a platform.

Power is delivered to the trains over a third rail, whose position alternates with respect to the train depending on context. Inside stations, the third rail is always on the side furthest away from the passenger platforms. This design feature eliminates the danger of a passenger either falling directly on the third rail, or stepping onto it to climb back to the platform should they fall off. On ground-level trackways, the third rail also is alternated from one side of the track to the other, providing breaks in the third rail to allow for emergency evacuations across trackways.

Underground tunnels, aerial structures and the transbay tube also have evacuation walkways and passageways to allow for train evacuation without exposing passengers to easy, inadvertent contact with the third rail, which is located as far away from these walkways as possible. The voltage over the third rail is 1000 V DC (1 kV DC); as a result, there are numerous notices through the system to warn passengers of its danger. BART also posts notices in each train car warning of the third rail and of the four paddle-like rail contact shoes that protrude from the underside of each car by the rail wheel trucks.

The BART system operates five lines, but most of the network consists of more than one line on the same track. Trains on each line typically run every 15 minutes on weekdays and 20 minutes during the evenings, weekends and holidays; however, since a given station might be served by as many as four lines, it could have service as frequently as every 3-4 minutes. As of 2006, BART service begins around 4:00 a.m. on weekdays, 6:00 a.m. on Saturdays, and 8:00 a.m. on Sundays. Service ends every day around midnight with station closings timed to the last train at station.

Current lines

Unlike most other rapid transit and rail systems around the world, BART lines are consistently not referred to by shorthand designations by the system's users and officials. Although the lines have been colored consistently on BART system maps for more than a decade, they are never referred to officially by colour names (for example, "Red Line"), and only rarely referred to in this way by members of the public. Each line is generally identified on maps and schedules by the names of its termini (for example, "Richmond - Daly City Line"). Since some routes have changed over the years, referring to routes by termini rather makes the change less "painful" for riders.

Trains are merely referred to by their destination or destinations by train operators and BART personnel (for example, "Richmond train" or "Richmond-bound train"). Electronic destination signs add "San Francisco" to the destination of any westbound transbay train or eastbound train west of San Francisco to make it clear that it will be passing through the City, and "SFO Airport" (or just "SFO") is added to any train going to the airport. This can cause quite cumbersome destination descriptions, such as "San Francisco/Daly City train", "San Francisco/SFO Airport/Millbrae train", and "San Francisco/Pittsburg/Bay Point train." Perhaps the worst such description is for trains leaving Millbrae, which say "San Francisco/SFO Airport/Dublin/Pleasanton."

Rolling stock

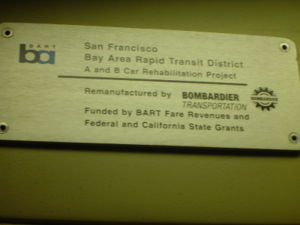

BART operates four types of cars, built in three separate orders. The A and B cars were built from 1968 to 1971 by Rohr Industries. The A cars, made to be leading or trailing cars only, have a fibreglass operator's cab with equipment to control the train and BART's two-way communication system. They can comfortably seat 72 passengers, and under crush load can hold 150 passengers. The B cars have no operator's cab and are used in the middle of trains to carry passengers only; these cars have the same passenger capacity as the A cars. Currently, BART operates 137 A Cars and 303 B cars. The C cars were built from 1987 until 1989 by Alstom. The C cars have the same fibreglass operator's cab and control and communications equipment as the A cars, but unlike A cars, can act as middle cars as well. The dual purpose of the C cars allow train sizes to be changed quickly without having to move the train to a switching yard. The C cars can comfortably seat 64 passengers and under crush load can fit 150 passengers. The last order, from Morrison-Knudson Corporation, was for C2 cars. C2 cars are essentially the same as C cars, but have a newer, third-generation interior featuring a blue/gray motif, in contrast to the older blue and brown colors. C2 cars feature flip-up seats near side exit/entry doors to accommodate passengers in wheelchairs and have red lights on posts near the door to warn deaf and hearing-impaired passengers when doors are about to close. C2 cars can comfortably seat 68 passengers, and under crush load can carry 150 passengers. Currently, BART operates 150 C1 cars and 80 C2 cars. From 1995 through 2002, the 439 original Rohr cars were rehabilitated/overhauled by ADtranz and Bombardier, which had acquired ADtranz by the end of the project. Refurbishment of the fleet was financially attractive compared to purchasing new custom trains to fit BART's non-standard track gauge and extended its useful life for about 20 years. The older vintage brown seats were converted to light-blue ones, which can be removed easily for washing or replacement.

All of the BART cars have upholstered seats and many cars have carpeting, although this is being removed for maintenance reasons and due to the prevalence of bicycles on trains. One of the original design goals of BART was that all passengers would have a seat. Therefore, many of the older cars have poor provisions for standees, such as few vertical grab bars. Newer cars, in contrast, have more grab bars, fewer seats facing each other, and flip up seats to accommodate wheelchairs and bicycles. However, unlike many urban transit systems, hand straps are not to be found on BART.

The cars, which all have just two doors on each side, often cause extended wait times at stations as passengers must negotiate groups of standees in order to exit or enter the train. To speed up service, BART has considered introducing new, three-door cars. (Bart cars must have doors on both sides as some stations have central platforms while others have platforms on each side of central two-way tracks.)

Governance

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District is a special governmental agency created by the State of California consisting of Alameda County, Contra Costa County, and San Francisco County. It is governed by an elected Board of Directors with each of the nine directors representing a specific geographic area within the BART district. BART has its own police force.

While the district includes all of the cities and communities in its jurisdiction, some of these cities do not have stations on the BART system. This has caused tensions in places like Livermore which pay BART taxes but receive no BART service. In addition, in areas like Fremont, the majority of commuters do not commute in the direction that BART would take them (many Fremonters commute to San Jose, where there is currently no BART service). This particular instance of the problem would be alleviated with the completion BART-to-San Jose extension project, if it ever went forward.

However, some cities and towns are near enough to cities with BART stations that residents commute via a bus or car to the nearest BART station. Emeryville, for instance, has no BART service, but has a free shuttle service, the Emery-Go-Round, that takes passengers to the nearby MacArthur station. For those wishing to drive their cars to the stations instead, many BART stations offer many kinds of parking options.

Cost and budget

BART's initial cost was $1.6 billion, which included both the initial system and the Transbay Tube. Adjusted for inflation, this cost would be valued at $15 billion in 2004.

In 2005, BART required nearly $300 million in subsidies after fares. About 37% of the costs went to maintenance, 29% to actual transportation operations, 24% to general administration, 8% to police services, and 4% to construction and engineering.

In 2005, 53% of the budget came from fares, 32% came from taxes, and 15% came from "other sources", such as advertising, leasing station space to vendors, and parking fees. BART's farebox recovery ratio of 0.53 is considered very high for a US public transit agency operating over such long distances with high frequency. It is often favorably compared to the ratio of the nearby Caltrain diesel commuter rail operation and is presented as an argument for an extension of BART all around the bay.

Fares

Fares on BART are comparable to that of commuter rail systems and are higher than that of most metros, especially for long trips. The fare is based on a formula that takes into account both the length and speed of the trip. A surcharge is added for trips traveling through the Transbay Tube, to San Francisco International Airport, or through San Mateo County, which is not a BART member. Historically and up to this day, passengers have used non-refillable paper tickets, on which fares are stored via a magnetic strip, to enter and exit the system. The exit faregate prints the remaining balance on the ticket each time the passenger exits the station. Even though a given card is not refillable, the remaining balance on any ticket can be applied towards the purchase of a new one. A trial program using thin refillable plastic farecards valid for many rides, called the TransLink smart card, is currently in progress, with systemwide rollout expected to be completed by mid-2007. The program was launched to the general public in fall 2006 with rollout on AC Transit, Dumbarton Express, and Golden Gate Transit lines. The cards are not expected to be fully implemented on BART until sometime in 2007.

The minimum fare is $1.40, charged for trips under six miles (9.6 km), and the maximum fare is $7.65 for the 51-mile (82 km) journey between Pittsburg/Bay Point and San Francisco International Airport, consisting of the regular fare and all possible surcharges. Passengers without enough fare to complete their journey must use an AddFare machine to pay the remaining balance in order to exit the station. Because of the amount of the base fare, traveling between BART stations in downtown San Francisco on BART is slightly cheaper than the city's own light rail system, the MUNI Metro, which is also generally slower covering the same distance and costs $1.50. However, MUNI permits around two full hours of riding, including transfers to other MUNI vehicles, whereas BART charges $1.40 for a single journey. There are various quirks in the fare system due to a subsidy being provided to riders traveling between some outlying stations. For example, for a trip from Dublin/Pleasanton to Fremont, it is less expensive to exit the station at the transfer point, Bay Fair, and re-enter the station, instead of staying on the platform, because you would get charged two $1.40 base fares instead of a $3.90 fare from end to end.

BART uses a system of five different colour-coded tickets for regular fare, special fare, and discount fare to select groups as follows:

- Blue tickets – General: the most common type, includes high-value discount tickets

- Red tickets – Disabled Persons and children aged 4 to 12: 62.5% discount, special ID required (children under the age of 4 ride free)

- Green tickets – Seniors age 65 or over: 62.5% discount, proof of age required for purchase

- Orange tickets – Student: special, restricted-use 50% discount ticket for students age 13-18 currently enrolled in high or middle school

- BART Plus – special high-value ticket with 'flash-pass' privileges with regional transit agencies, including MUNI's buses.

Unlike most transit systems in the United States, but like the MRT in Singapore, BART does not have an unlimited ride pass available and riders must pay for each ride they take. The only discount provided to the general public is a 6.25% discount when "high value tickets" are purchased with fare values of $48 and $64. Capitol Corridor trains sell $10 BART tickets on-board in the café cars for only $8, resulting in a 20% discount. A 62.5% discount is provided to seniors, the disabled, and children age 5 to 12. Middle and high school students 13 to 18 may obtain a 50% discount if their school participates in the BART program; however, these tickets are intended to be used only between the students' home station and the school's station and for transportation to and from school events. However, these intended limitations are not enforced in any way and students are expected to behave on the honour system. Also, the tickets may only be used on weekdays, a restriction that is actually enforced by the faregates. BART Plus tickets enjoy a last-ride bonus where if the remaining value is greater than 5 cents, the ticket can be used one last time for a trip of any distance. The special tickets must be purchased at selected vendors and not at ticket machines. In particular, the middle and high school tickets are usually sold at the schools themselves.

Family members of BART employees, however, receive special BART passes and can ride free-of-charge upon showing their pass and photo identification to the BART station attendant.

Fares are enforced by the station agent, who monitors activity at the fare gates adjacent to the window and at other fare gates through closed circuit television and faregate status screens located in the agent's booth. All stations are staffed with at least one agent at all times. Despite this, fare fraud occasionally occurs, usually as a result of people entering and exiting through the emergency exit gate.

There is little fare coordination between BART and surrounding agencies. Some agencies accept the BART Plus pass, which at a fee of between $42 and $46 per month, permits pass holders to use BART and connecting buses. Most notably, AC Transit dropped out of the program due to the small amount of reimbursement they received from BART. Aside from that, there is only a token discount (25 to 50 cents) provided to passengers transferring to and from trains to other transit modes. One fare coordination program permits adult monthly pass holders of the San Francisco Municipal Railway to ride BART trains within the City of San Francisco for free (with no credit applied to trips outside the City). The City pays BART 87 cents for each trip taken under this arrangement.

Automation

BART was one of the first US systems of any size to have substantial automated operations. The trains are computer-controlled via BART's Operations Control Centre (OCC) and headquarters at Lake Merritt and generally arrive with regular punctuality. Train operators are present to make announcements, close doors, and operate the train in case of unforeseen difficulties.

As a first generation system, BART's automation system was plagued with numerous operational problems during its first years of service. Shortly before revenue service began, an on-board electronics failure caused one empty 2-car test train, dubbed the "Fremont Flyer", to run off the end of the platform at its namesake station into a parking lot, though there were no injuries. When revenue service began, "ghost trains", trains that show up on the computer system as being in a specific place but don't physically exist, were common, and real trains could at times disappear from the system, as a result of dew on the tracks and too low of a voltage being passed through the rails for detecting trains. Under such circumstances, trains had to be operated manually and were restricted to a speed of 25 mph (about 40 km/h). In addition, the fare card system was easily hackable with equipment commonly found in universities, although most of these flaws have been fixed.

During this initial shakedown period, there were several episodes where trains had to be manually run and signaled via station agents communicating by phone. This caused a great outcry in the press and led to a flurry of litigation among Westinghouse, the original controls contractor, and BART, as well as public battles between the state government (advised by University of California professor Dr. Bill Wattenburg), federal government, and the district, but in time these problems were resolved and BART became a reliable service. Ghost trains apparently still persist on the system to this day and are usually cleared quickly enough to avoid significant delay, but occasionally some can cause an extended backup of manually operated trains in the system. BART does not operate two-car trains per PUC requirements, even though it is operationally feasible.

Connecting rail and bus transit services

BART has direct connections to two regional rail services – Caltrain, which provides service between San Francisco, San Jose, and Gilroy, at the Millbrae Station, and Amtrak's Capitol Corridor, which runs from Sacramento to San Jose, at the Richmond and Coliseum/Oakland Airport stations. A third Capitol Corridor connection at the Union City station is planned as part of a larger Dumbarton Rail Corridor Project to connect Union City, Fremont, and Newark to various Peninsula destinations via the Dumbarton rail bridge. BART is also the managing agency for the Capital Corridor until 2010.

In addition, BART connects to San Francisco's local light rail system, the Muni Metro. The upper track level of BART's Market Street subway, originally designed for the lines to Marin County, was turned over to Muni and both agencies share the Embarcadero, Montgomery Street, Powell and Civic Centre stations. In addition, some Muni Metro lines connect with (or pass by) the BART system at the Balboa Park and Glen Park stations.

A number of bus services connect to BART, which, while managed by separate agencies, are integral to the successful functioning of the system. The primary providers include the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni), Alameda-Contra Costa Transit (AC Transit), San Mateo County Transit District (SamTrans), Central Contra Costa Transit Authority (County Connection), and the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District ( Golden Gate Transit). Until 1997, BART ran its own "BART Express" connector buses, which ran to eastern Alameda County and far eastern and western areas of Contra Costa County; these routes were later devolved to subregional transit agencies such as Tri-Delta Transit and the Livermore Amador Valley Transit Authority ( WHEELS) or, in the case of Dublin/Pleasanton service, replaced by a full BART extension.

BART is connected to Oakland International Airport via AirBART shuttle buses, which bring travelers to and from the Coliseum/Oakland Airport BART station. These buses are operated by BART and accept exact-change BART fare cards as fare in addition to exact change. BART also connects to the San Francisco International Airport, though in this case the train actually enters the airport directly and no shuttle is necessary.

Smaller services connect to BART as well and include the Emery Go Round ( Emeryville), WestCat (northwestern Contra Costa County), Benicia Transit ( Benicia), Union City Transit ( Union City), and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA, in Silicon Valley).

The bus service connecting the University of California, Berkeley to the Berkeley BART station was once called Humphrey Go-BART, a spoonerism of the famous actor and director Humphrey Bogart. It has since been replaced by a number of regular AC Transit bus routes.

Other connecting services

BART hosts Car Sharing locations at a number of stations, a program pioneered by City CarShare. Riders can transfer from BART, and complete their journeys by car.

Casual Car Pools have formed at several stations.

History of BART

Origins and planning

A rapid transit system in the San Francisco Bay Area was first proposed in 1946 by Bay Area business leaders concerned with increased post-war migration and congestion in the region. An Army-Navy task force concluded that another trans-bay crossing would soon be needed to relieve congestion on the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. The idea of an underwater electric rail tube, first proposed in the early 1900s by Francis "Borax" Smith of the Key System, was deemed the best solution in conjunction with a multiple-county rapid transit rail system.

In fact, much of BART's current territory was earlier covered by the Key System, an electrified streetcar and suburban train network that had its origins in the 1900s and ran across the lower deck of the Bay Bridge when it first opened; however, this system was removed in the 1950s due to the combined pressures of declining ridership, the automotive industry, and highway planners.

However, it was not until the 1950s that the actual planning for a rapid transit system would begin. In 1951, California's legislature created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission to study the Bay Area's long term transportation needs. The commission's 1957 final report recommended that the cheapest solution to reduce traffic tie-ups would be to form a rapid transit district that would build and operate a high-speed rapid rail system linking the cities with the suburbs. Nine counties in the region were involved in planning.

Acting on the recommendations, the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District was formed by the state legislature in 1957, comprising the counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo. Santa Clara County was left out of the initial stage of building, though both the proposed Palo Alto and Fremont lines could have provided service, and opted to build the Santa Clara County Expressway System instead.

By 1961, a final plan for the new system was sent to the supervisors of the five counties within the BART district for approval. The system was supposed to consist of lines to Concord, Richmond, Fremont, Arastradero Road in Palo Alto, and Novato. Each county approved the system except for San Mateo County. Instead, the San Mateo County supervisors voted to opt out of the district, citing high costs and existing service provided by Southern Pacific commuter trains. San Mateo county was also supposedly concerned about shoppers leaving the county's stores for those in San Francisco, and was of the opinion that a San Mateo line would mostly carry Santa Clara County commuters. A year later, Marin County was also forced to withdraw because the engineering feasibility of carrying trains across the Golden Gate Bridge was under dispute. Plus, Marin County's tax base could not adequately pay for its share of BART's projected cost, which had grown considerably after the departure of San Mateo County. The plans for BART were finally approved by the voters of each participating county in 1962.

Construction of the initial system

BART construction officially began on June 19, 1964. President Lyndon Johnson presided over the ground-breaking ceremonies at a 4.4 mile (7.1 km) test track between Concord and Walnut Creek in Contra Costa County.

Enormous construction tasks were at hand, including underground rail sections in downtown Oakland, Market Street in San Francisco, and Berkeley; a 3.5-mile (5.6 km) tunnel through the Berkeley Hills; and the 3.6 mile (5.8 km) Transbay Tube between Oakland and San Francisco beneath the San Francisco Bay. The tube is the world's longest and deepest immersed tunnel and was constructed in 57 sections. It was completed in August 1969 at a cost of $180 million.

Operation

BART began regular passenger service on September 11, 1972. President Richard Nixon rode the system on September 27, 1972. The Transbay Tube opened nearly two years later on September 16, 1974, completing the original system, which had four branches extending to Daly City, Concord, Richmond, and Fremont.

In January 1979, an electrical fire broke out on a train traveling in the Transbay Tube, killing one firefighter. Service was halted for over two months. The trains were more flammable than permitted by current codes. Since then, BART holds regular fire drills and has used fire-resistant seating in its trains.

In the aftermath of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, most of the major San Francisco freeways were too damaged for car travel, but the BART system was specially designed to withstand earthquakes. Six hours after the quake, the trains were operational, and BART became the sole form of transportation for much of the Bay Area, including the shipment of relief supplies to the more damaged areas of San Francisco and Oakland. Nonetheless, the trains are routinely halted for several hours following minor earthquakes while maintenance crews inspect tracks, over- and under-crossings, and tunnels for damage before service is restored.

Extensions to the original system were made possible by a regional agreement under which San Mateo County contributed $200M to East Bay extensions as a way of buying into the BART system without actually joining the BART district. The North-of-Concord extension opened in two phases, with service to North Concord/Martinez beginning on December 16, 1995 and service to Pittsburg/Bay Point beginning just under a year later on December 7, 1996. The first service south of Daly City Station began on February 24, 1996, to Colma Station. Over a year later, the Dublin/Pleasanton extension was finally completed, and service to Castro Valley and Dublin/Pleasanton began on May 10, 1997.

BART has a unionized work force that went on strike for six days in 1997, causing great inconvenience to the public. In its 2001 negotiations, BART unions won 24 percent wage increases over four years and continuing generous benefits for employees and retirees. Another threatened strike on July 6, 2005 was averted by a last-minute agreement between management and the unions.

In October 2004, BART received the American Public Transportation Association 2004 Outstanding Public Transportation System award for transit systems with 30 million or more annual passenger trips. BART issued announcements and began a promotional campaign declaring that it had been named #1 Transit System in America by APTA, but no such award or title is currently given by the organization.

San Francisco International Airport extension

A $1.5 billion extension of BART southward to San Francisco International Airport's (SFO) Garage G, next to the International Terminal, was completed in June 2003. Ground was broken in November 1997, and the extension added three new stations in addition to the SFO station – South San Francisco, San Bruno, Millbrae, the last of which had a cross-platform connection to Caltrain, the first of its kind west of the Mississippi River. The project encompassed 8.7 miles (14 km) of new rail track, of which 6.1 miles (9.8 km) is subway, 1.2 miles (1.9 km) is aerial, and 1.4 miles (2.2 km) is at-grade. The precursor project for the airport extension was the Daly City Tailtrack project, which allowed track to be laid considerably south of its then existing terminus in San Francisco; this precursor work was carried out in the 1980s.

However, problems have plagued this extension since it opened. To date, it has drawn far fewer riders than anticipated, forcing BART to cease claiming that it remained on track on its target of 50,000 average weekday riders. Many commuters find it faster to take Caltrain from Millbrae to downtown San Francisco instead because that system has a more direct express route, albeit with a slightly higher fare. Secondly, since San Mateo County is not part of the BART district and does not pay taxes directly to the district, the San Mateo County Transit District is responsible for the extension's operating costs. The extension had been projected to be financially self-sufficient, but this expectation has turned out to be unrealistic. Thus, service along the extension has been changed four times. Service has been reduced from eight trains per hour to four trains per hour on the extension. Critics contend that the SFO Airport Extension was merely a cover for the goal of BART around the bay, which would most likely result in the elimination of Caltrain.

Future expansion and extension

Warm Springs & San Jose extensions

A 5.4-mile extension of BART southward past Fremont to the Warm Springs District in southern Fremont, with an optional station at Irvington between the Fremont and Warm Springs stations, is in the planning and engineering stage by BART planning staff. This extension received a green light from the federal government when the Federal Transit Administration issued a Record of Decision on October 24, 2006. The action allows BART to begin purchasing the necessary right-of-way for the project and receive state-administered federal funding to finance the project. A further, more controversial extension towards San Jose is also proposed by the transit district south of BART, the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA), but preliminary engineering remains to be completed and funding to be acquired. The VTA has allocated funds for constructing BART from a 2000 sales tax, but does not have enough money to pay for all of the other projects it promised to its residents. In addition, the San Jose extension project received a "not recommended" rating from the Federal Transit Administration due to the VTA's financial problems, potentially putting its future in jeopardy.

Oakland Airport Connector

Procurement is currently underway for a people mover that would directly connect the Coliseum station to the terminal buildings at Oakland International Airport. This connection would physically resemble the AirTrain connection to New York City's JFK Airport, in that passengers would leave standard subway cars at a nearby station and enter a specialized people mover to reach the airport itself. However, unlike the AirTrain, the Oakland Airport Connector will be operated by BART, and integrated into the BART fare system, with standard BART ticket gates located at the entrance to the station at the Airport end of the people mover. Construction of this extension is expected to start in 2007, with revenue service expected by 2011.

eBART

eBART calls for diesel multiple unit train service to be implemented from the existing Pittsburg/Bay Point station with a cross-platform transfer east along the Highway 4 corridor to the town of Byron, with the future possibility of service to Tracy in the San Joaquin Valley. New stations would be located in Pittsburg, Antioch, Oakley, Brentwood, and Byron. Another option would be a Caltrain-like service on the existing Union Pacific right-of-way from North Concord to Brentwood and beyond to Tracy and Stockton, though such a project would be subject to problems associated with using non-dedicated rights of way. Service is expected to start in 2010.

I-580/Tri-Valley Corridor

This extension of either conventional BART or diesel multiple unit BART service would go from Dublin/Pleasanton station east to Livermore and over the Altamont Pass into Tracy and the Central Valley along I-580. It could possibly also go north through Dublin, San Ramon, Danville, and Alamo to the existing Walnut Creek station via the I-680 corridor.

Currently, a petition to extend BART to Livermore is being circulated by Linda Jeffery Sailors, the former mayor of Dublin, California.

The extension of conventional BART rail to Tracy is considered unlikely, as San Joaquin County, in which Tracy is located, is not part of the nine district counties and does not pay into the regional BART tax. Additionally, an extension of third-rail BART over such a distance would be prohibitively expensive.

I-80/West Contra Costa Corridor

A corridor study of extending the service north from the Richmond Station is underway with numerous options being studied. One would create commuter rail service utilizing lightweight diesel multiple units (DMU) to operate on existing or new rail trackage. In order to operate on existing tracks with freight service, however, heavier-weight DMU vehicles adhering to Federal Railroad Administration regulations would need to be used. This option is also known as wBART. A second option would create a commuter rail service running from the BART terminus along the Amtrak line to Hercules and possibly Fairfield in Solano County, similar to the Caltrain or ACE services. Yet another option would extend convetional BART to a North Richmond station near the Richmond Trainyard at 13th Street/Rumrill Avenue and Market Street, then continue along the existing Southern Pacific rail line and the Richmond Parkway expressway to Interstate 80. The service would have a Hilltop station and then continue along I-80 to Highway 4 in Hercules, near Hercules Transit Centre. Service would continue along I-80 through Vallejo until Peabody Road in Fairfield.

Infill stations

BART has either planned, or studied the idea of, infill stations for three locations within the system. Infill stations are stations constructed on existing line segments between two existing stations. The 30th Street Mission station was planned for San Francisco between 24th Street Mission and Glen Park stations and was estimated to cost approximately $500 million to construct. The Jack London Square station in Oakland was studied and rejected as being incompatible with existing track geometry. A one-station stub line to Jack London Square at the foot of Broadway and the utilization of other transit modes was also studied. The West Dublin/Pleasanton station will be located in the median of I-580 just west of I-680 between Castro Valley and Dublin/Pleasanton stations. This station is expected to cost $71.5 million, with funding coming from a unique public-private partnership and the proceeds of planned transit-oriented development (TOD) on adjacent BART-owned property. Originally planned as a third station on the Dublin-Pleasanton extension, the station's foundation, along with some communication and train control facilities, already exist on-site. Construction on the station is scheduled to begin 29 October 2006, and is slated to be complete in 2009.

Recent news

| 2005 statistics | |

|---|---|

| Number of vehicles | 670 |

| Initial system cost | $1.6 billion |

| Equivalent cost in 2004 dollars | $15 billion |

| Hourly passenger capacity | 15,000 |

| Maximum daily capacity | 360,000 |

| Average weekday ridership | 310,717 |

| Annual gross fare income | $233.65 million |

| Annual expenses | $581.81 million |

| Annual profits (losses) | ($300 million) |

| Rail cost/passenger mile | 32.3 cents |

A recent study shows that along with some Bay Area freeways, some of BART's overhead structures would collapse in the event of a major earthquake, which is predicted as highly likely to happen in the Bay Area within the next 30 years. Extensive seismic retrofit will be necessary to address many of these deficiencies, although one in particular, the penetration of the Hayward Fault Zone by the Berkeley Hills Tunnel, will be left for correction after any disabling earthquake at that point, with the consequenses for in-transit trains, their operators, and their passengers left to chance.

On March 28 and 29, 2006, BART experienced a computer glitch in its system during rush hour, which left about 35,000 commuters stranded inside trains or stations while the problem was being resolved. The following month, BART's on-time performance hit a 16-month high. However, starting with a small fire that caused chaos on March 9, 2006, BART has experienced seven major delays, including the one above, which is claimed by some to point to a BART meltdown. Faulty equipment was the cause of three of the delays, including the latest on July 12. In two of the delays, the fire of March 9 and the debris incident on June 20, passengers were so scared and frustrated, respectively, that they self-evacuated, causing further delays and hassles for BART.

By November 2005, BART had become the first transit system in the nation to offer cellular communication to passengers of all wireless carriers on its trains underground. As of summer 2006, service is available for customers of Verizon Wireless, Sprint/Nextel, Cingular Wireless, and T-Mobile in and between the four San Francisco Market Street stations from Civic Centre to Embarcadero. This is in contrast to other systems in US, which, while having some cellular service, do not provide it for passengers of all the major cell phone carriers. Coverage is eventually planned for the entire system, with coverage for the segment between Balboa Park and 16th St. Mission by the middle of 2007 and between Lake Merritt and 19th St./Oakland at some time after that.

Since the mid 1990s, BART has been trying to modernize its aging 30-year-old system. The aforementioned fleet rehabilitation is part of this modernization; presently, fire alarms, water-sprinkling systems, yellow tactile platform edge domes, and cemented-mat rubber tiles are being installed. The rough black tiles on the platform edge mark the location of the doorway of approaching trains, allowing passengers to wait at the appropriate locations for the train, instead of waiting until the train arrives to figure out where to board. All faregates and ticket vending machines have also been completely replaced.