The Origin of Species

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Evolution and reproduction

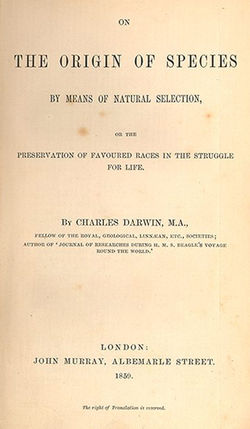

The Origin of Species (full title: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life) by British naturalist Charles Darwin, first published on 24 November 1859, is one of the pivotal works in scientific history and arguably the pre-eminent work in biology.

In it, Darwin makes "one long argument", with copious empirical examples as support, for his theory that organisms gradually evolve not individually but in "groups" (now called populations) through the process of natural selection, a mechanism the book effectively introduced to the public. The work presents detailed scientific evidence that Darwin had accumulated on the Voyage of the Beagle in the 1830s and since his return, painstakingly laying out his theory and refuting the doctrine of " Created kinds", which underlay the then widely accepted theories of Creation biology.

The book is quite readable even for the non-specialist and attracted widespread interest on publication. Although its ideas are supported by an overwhelming body of scientific evidence and are widely accepted by scientists today, they are still highly controversial in some parts of the world, particularly among American non-scientists who perceive them to contradict various religious texts (see Creation-evolution controversy).

Background

Before The Origin

The idea of biological evolution was supported in Classical times by the Greek and Roman atomists, notably Lucretius. With the rise of Christianity came belief in the Biblical idea of creation according to Genesis, with the doctrine that God had directly " Created kinds" of organisms which were immutable. Other ideas resurfaced, and in 17th century English the word evolution (from the Latin word "evolutio", meaning "unroll like a scroll") began to be used to refer to an orderly sequence of events, particularly one in which the outcome was somehow contained within it from the start.

Natural history, aiming to investigate and catalogue the wonders of God's works, developed greatly in the 18th century. Discoveries showing the extinction of species were explained by catastrophism, the belief that animals and plants were periodically annihilated as a result of natural catastrophes and that their places were taken by new species created ex nihilo (out of nothing). Countering this, James Hutton's uniformitarian theory of 1785 envisioned gradual development over aeons of time. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Charles Bonnet, Lord Monboddo and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck played roles in the foreshadowing of evolutionary thought in the mid 18th and early 19th centuries.

By 1796 Charles Darwin's grandfather Erasmus Darwin had put forward ideas of common descent with organisms "acquiring new parts" in response to stimuli then passing these changes to their offspring, and in 1802 he hinted at natural selection. In 1809 Jean-Baptiste Lamarck developed a similar theory, with "needed" traits being acquired then passed on. These theories of Transmutation were developed by Radicals in Britain like Robert Edmund Grant. At this time the work of Thomas Malthus showing that human populations increased to exceed resources influenced liberal thinking, resulting in the Whig Poor Law of the 1830s.

Various ideas were developed to reconcile Creation biology with scientific findings, including Charles Lyell's uniformitarian idea that each species had its "centre of creation" and was designed for the habitat, but would go extinct when the habitat changed. Charles Babbage believed God set up laws that operated to produce species, as a divine programmer, and Richard Owen followed Johannes Peter Müller in thinking that living matter had an "organising energy", a life-force that directed the growth of tissues and also determined the lifespan of the individual and of the species.

The publication of the anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation ( 1844) then paved the way for the acceptance of Origin.

Inception of Darwin's theory

Charles Darwin's education at the University of Edinburgh gave him direct involvement in Robert Edmund Grant's evolutionist developments of the ideas of Erasmus Darwin and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Then at Cambridge University his theology studies convinced him of William Paley's argument of "design" by a Creator while his interest in natural history was increased by the botanist John Stevens Henslow and the geologist Adam Sedgwick, both of whom believed strongly in divine creation and in a uniformitarian ancient earth. During the Voyage of the Beagle Charles Darwin became convinced by Charles Lyell's uniformitarianism, and puzzled over how various theories of creation fitted the evidence he saw. On his return Richard Owen showed that fossils Darwin had found were of extinct species related to current species in the same locality, and John Gould startlingly revealed that completely different birds from the Galápagos Islands were species of finches distinct to each island.

By early 1837 Darwin was speculating on transmutation in a series of secret notebooks. He investigated the breeding of domestic animals, consulting William Yarrell and reading a pamphlet by Yarrell's friend Sir John Sebright which commented that "A severe winter, or a scarcity of food, by destroying the weak and the unhealthy, has all the good effects of the most skilful selection." At the zoo in 1838 he had his first sight of an ape, and the orang-utan's antics impressed him as being "just like a naughty child" which from his experience of the natives of Tierra del Fuego made him think that there was little gulf between man and animals despite the theological doctrine that only mankind possessed a soul.

In late September 1838 he began reading the 6th edition of Malthus's Essay on the Principle of Population which reminded him of Malthus's statistical proof that human populations breed beyond their means and compete to survive, at a time when he was primed to apply these ideas to animal species. Darwin applied to his search for the Creator's laws the Whig social thinking of struggle for survival with no hand-outs. By December 1838 he was seeing a similarity between breeders selecting traits and a Malthusian Nature selecting from variants thrown up by chance so that "every part of newly acquired structure is fully practised and perfected", thinking this "the most beautiful part of my theory".

First writings on the theory

Darwin was well aware of the implication the theory had for the origin of humanity and the real danger to his career and reputation as an eminent geologist of being convicted of blasphemy. He worked in secret to consider all objections and prepare overwhelming evidence supporting his theory. He increasingly wanted to discuss his ideas with his colleagues, and in January 1842 sent a tentative description of his ideas in a letter to Lyell, who was then touring America. Lyell, dismayed that his erstwhile ally had become a Transmutationist, noted that Darwin "denies seeing a beginning to each crop of species".

Despite problems with illness, Darwin formulated a 35 page "Pencil Sketch" of his theory in June 1842 then worked it up into a larger " essay". The botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker became Darwin's mainstay, and late in 1845 Darwin offered his "rough Sketch" for comments without immediate success, but in January 1847 when Darwin was particularly ill Hooker took away a copy of the "Sketch". After some delays he sent a page of notes, giving Darwin the calm critical feedback that he needed. Darwin made a huge study of barnacles which established his credentials as a biologist and provided more evidence supporting his theory.

Publication

In the spring of 1856 Lyell drew Darwin's attention to a paper on the "introduction" of species written by Alfred Russel Wallace, a naturalist working in Borneo, and urged Darwin to publish to establish priority. Darwin was now torn between the desire to set out a full and convincing account and the pressure to quickly produce a short paper. He ruled out exposing himself to an editor or counsel which would have been required to publish in an academic journal. On 14 May 1856 he began a "sketch" account and, by July, had decided to produce a full technical treatise on species.

Darwin pressed on, overworking, and was throwing himself into his work with his book on Natural Selection well under way, when on 18 June 1858 he received a parcel from Wallace enclosing about twenty pages describing an evolutionary mechanism, an unexpected response to Darwin's recent encouragement, with a request to send it on to Lyell. Darwin wrote to Lyell that "your words have come true with a vengeance,... forestalled" and he would, "of course, at once write and offer to send [it] to any journal" that Wallace chose, adding that "all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed". Lyell and Hooker agreed that a joint paper should be presented at the Linnean Society, and on 1 July 1858 the Wallace and Darwin papers entitled respectively On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection were read out, to surprisingly little reaction.

Darwin now worked hard on an "abstract" trimmed from his Natural Selection, writing much of it from memory. Lyell made arrangements with the publisher John Murray, who agreed to publish the manuscript sight unseen, and to pay Darwin two-thirds of the net proceeds. Darwin had decided to call his book An Abstract of an Essay on the Origin of Species and Varieties through Natural Selection, but with Murray's persuasion it was eventually reduced to the snappier On the Origin of Species through Natural Selection.

Publication of The Origin

The Origin was first published on 24 November 1859, price fifteen shillings, and was oversubscribed, so that all 1250 copies were claimed by booksellers that day. The second edition came out on 7 January 1860, and added "by the Creator" into the closing sentence, so that from then on it read "There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved."

During Darwin's lifetime the book went through six editions, with cumulative changes and revisions to deal with counter-arguments raised. The third edition came out in 1861, and the fourth in 1866, each with an increasing number of sentences rewritten or added. The fifth edition published on 10 February 1869 incorporated more changes again, and for the first time included Herbert Spencer's phrase " survival of the fittest".

In January 1871 Mivart published On the Genesis of Species, the cleverest and most devastating critique of natural selection in Darwin's lifetime. Darwin took it personally and from April to the end of the year made extensive revisions to the Origin, using the word "evolution" for the first time and adding a new chapter to refute Mivart. He told Murray of working men in Lancashire clubbing together to buy the 5th edition at fifteen shillings, and he wanted a new cheap edition to make it more widely available.

The sixth edition was published by Murray on 19 February 1872 with "On" dropped from the title, at a price halved to 7s. 6d. by using minute print. Sales increased from 60 to 250 a month.

Darwin's theory, as presented

Darwin opened his argument by pointing to the results of domestication, mostly through artificial selection (though environmental changes, such as more food and protection from predators, were also factors). Comparing domesticated and wild varieties, Darwin showed that the nineteenth-century definition of species was chiefly a matter of opinion, since the discovery of new linking forms often degraded species to varieties.

Basic theory

Darwin's theory is based on five key observations and inferences drawn from them, as summarized by the biologist Ernst Mayr:

- Species have great fertility. They make more offspring than can grow to adulthood.

- Populations remain roughly the same size, with modest fluctuations.

- Food resources are limited, but are relatively constant most of the time. From these three observations it may be inferred that in such an environment there will be a struggle for survival among individuals.

- In sexually reproducing species, generally no two individuals are identical. Variation is rampant.

- Much of this variation is inheritable.

From this Darwin infers: In a world of stable populations where each individual must struggle to survive, those with the "best" characteristics will be more likely to survive, and those desirable traits will be passed to their offspring; and that these advantageous characteristics are inherited by following generations, becoming dominant among the population through time. This is natural selection.

Darwin did not suggest that every variation and every character must have a selection value. However, he pointed out that, because of our ignorance of animal physiology and its relationship with the environment, it was extremely rash to set down any characters as valueless to their owners. It is even more important to notice that he did not suggest that every individual with a favorable variation must be selected, or that the selected or favored animals were better or higher, but merely that they were more adapted to their surroundings.

Darwin further infers that natural selection, if carried far enough, makes changes in a population, eventually leading to new species. He puts forward myriad observations as demonstrations of this, and also claims that the fossil record can be interpreted as supporting these observations. Darwin imagined it might be possible that all life is descended from an original species from ancient times. Modern DNA evidence is consistent with this idea.

In later editions of his book, starting in the fifth edition, in some instances where Darwin used the wording, Natural Selection, this was modified to "Natural Selection, or the Survival of the Fittest" in varying ways, borrowing the term survival of the fittest from Herbert Spencer.

Variation and heredity

One of the chief difficulties for Darwin and other naturalists in his time was that there was no agreed-upon model of heredity — in fact, the idea of heredity had not been completely separated conceptually from the idea of the development of the organism. Darwin himself saw variation and heredity as two essentially antagonistic forces, with most heredity working to preserve the fixity of a type rather than acting as the agent of species variability. Darwin's own model of heredity worked out in later works, which he dubbed " Pangenesis", was a mixture of a number of different ideas about heredity at the time. It contained what are now considered to be essentially Lamarckian aspects, whereby the effects of use and dis-use of different parts of the body in the parent could be transmitted to the child. Beyond this, it was essentially a model of "blended" heredity, by which the contributions of two parents (in the form of particles he called "gemmules") were roughly equal. Darwin was confident that even in this model, over long periods of time species would still be able to evolve.

It was not until the early twentieth century that a model of heredity would become completely integrated with a model of variation, with the advent of the modern evolutionary synthesis known as neo-Darwinism. It is a common trope in the history of evolution and genetics written by scientists, rather than historians, to claim that Darwin's lack of an adequate model of heredity was the source of suspicion about his theory, but later historians of science have adequately documented the fact that this was not the source of most objections to Darwin, and that later scientists, such as Karl Pearson and the biometric school, could develop compelling models of evolution by natural selection with even a relatively simple "blending" model of heredity such as that used by Darwin. (Bowler 1989)

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Compatibility with Lamarckian inheritance

Contrarily to a common opinion, Darwin did not rule out at first the possibility of inherited acquired traits, and even mentions it explicitly in chapter 7 :

"When the first tendency was once displayed, methodical selection and the inherited effects of compulsory training in each successive generation would soon complete the work; and unconscious selection is still at work, as each man tries to procure, without intending to improve the breed, dogs which will stand and hunt best. On the other hand, habit alone in some cases has sufficed; no animal is more difficult to tame than the young of the wild rabbit; scarcely any animal is tamer than the young of the tame rabbit; but I do not suppose that domestic rabbits have ever been selected for tameness; and I presume that we must attribute the whole of the inherited change from extreme wildness to extreme tameness, simply to habit and long-continued close confinement".

Nevertheless, there is a quantum leap between Lamarck's theory and Darwin's one: while Darwin's theory stays valid whether acquired traits are transmitted or not, Lamarck's theory becomes inoperative if acquired traits cannot be transmitted.

Public reaction

After the publication of Darwin's book, evolution was widely discussed and debated. As well as attracting attention from naturalists and learned religious people, Huxley's "working-men's lectures" proved very popular and the 6th edition was halved in price, successfully increasing sales to meet this demand.

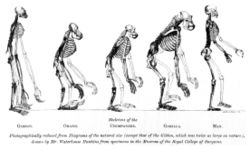

The book was highly controversial when first published, as it contradicted the then-prevailing theory of establishment scientists, of immediate, divine design in nature, and conflicted with a literal reading of the biblical creation stories in the Book of Genesis. Most of the debates did not centre around Darwin's specifically proposed mechanism for evolution — natural selection — but rather on the concept of evolution in general, which Darwin was credited for having given compelling scientific support. Though Darwin himself was too sickly to defend his work in public, four of his close scientific friends took up the cause of promoting Darwin's work and defending it against critics. Chief among these were Thomas Henry Huxley, who argued for the evidence of evolution in anatomical morphology, and Joseph Dalton Hooker, the Royal botanist at Kew Gardens. In the United States, Asa Gray worked in close correspondence with Darwin to assure the theory's spread despite the opposition of one of the most prominent scientists in the country at the time, Louis Agassiz, and helped to facilitate American publication of the book. Darwin himself worked over the years with translators who published his work in both French and German as well.

Scientific reaction to Darwin's theory was mixed. Many well-respected members of the scientific community, such as the aforementioned Agassiz and the anatomist Richard Owen, came out strongly against Darwin's work. On the whole, though, Darwin was successful in convincing many scientists, especially of the younger generations, that evolution had happened in one form or another. Over the course of the next two decades, most scientists and educated lay-people would come to believe that evolution had occurred. Natural selection, though, did not find wide support, and was actively attacked and relatively unpopular until its revival during the creation of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1920 and 1930s. Similarly, Darwin's notion that evolution occurred gradually was also often attacked, and many of the evolutionary theories which flourished during what Peter J. Bowler has called the "eclipse of Darwinism" were forms of " saltationism", in which new species arose through "jumps" rather than gradual adaptation.

In 1874, the theologian Charles Hodge accused Darwin of denying the existence of God by defining humans to be a result of a natural process rather than a creation designed by God. This is an argument that had been made by many almost immediately after Darwin's first publication. Evolution is in complete contradiction with literal readings of many of the legendary or religious stories of how the world's life originated; therefore, those who accepted the theory grew more skeptical of the Bible or other religious sources. As Hodge pointed out, evolution does not seem to originate from a divine source, and some viewed God as a less powerful force in the universe.

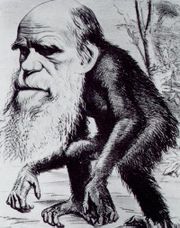

Darwin's theory changed the way humans saw themselves and their world. If one accepted that humans were descended from animals, it became clear that humans also are animals. The natural world took on a darker tinge in the minds of many, as animals in the wild are understood to be in a constant state of deadly competition with one another. The world was also seen in a less permanent fashion; since the world was apparently much different millions of years ago, it dawned on many that the impact of human beings would lessen and perhaps disappear altogether over time.

From the 1860s up until the 1930s, Darwinian "selectionist" evolution was not universally accepted by scientists, while evolution of some form generally was (a variety of evolutionary theories competed for scientific approval, including neo-Darwinism, neo-Lamarckism, orthogenesis, and mutation theory). In the 1930s, the work of a number of biologists and statisticians (especially R. A. Fisher) created the modern synthesis of evolution, which merged Darwinian selection theory with sophisticated statistical understandings of Mendelian genetics.

Today, whilst the overwhelming majority of scientists in the fields of earth and life sciences (over 99.9%) consider Darwin's theory correct , a significant proportion of non-scientists in the United States and a few other countries disagree mainly on religious grounds (see creation-evolution controversy).

Misconceptions, and comparison to Wallace's theory

Like many great scientists, Darwin did not invent his theory from the ground up, rather, he seized upon earlier research to create a comprehensive and defendable theory. Darwin did not "discover" evolution as is clear from the history of evolutionary thought. Even in his own day it was a well-known concept, although not one defended by the scientific community. As he subsequently acknowledged, others before him published brief statements outlining the principle of natural selection, but he was not aware of these little known statements until after publication of the Origin. Instead, he and Wallace put forth the first convincing and coherent mechanism of evolution: natural selection. Darwin's work, through its long list of facts and its support by prominent naturalists, established for most that evolution of some form did occur—that there was no fixity of species—even if there was considerable disagreement on the mechanism. Also contrary to a common understanding, Darwin did not invent the phrase " survival of the fittest", but added this in the 5th edition of The Origin of Species, giving due credit to the philosopher Herbert Spencer (who had introduced the phrase in his Principles of Biology of 1864) and usually using the phrase "Natural Selection, or the Survival of the Fittest". Other aspects of Darwin's overall theory which themselves evolved over time were: common descent, sexual selection, gradualism, and pangenesis.

Darwin's explanation of natural selection was slightly different from that given by Wallace. Darwin used comparison to selective breeding and artificial selection as a means for understanding natural selection. No such connection between selective breeding and natural selection was made by Wallace; he expressed it simply as a basic process of nature and did not think the phenomena were in any way related. On Wallace's own first edition of The Origin of Species, he crossed out every instance of the phrase "natural selection" and replaced with it Spencer's "survival of the fittest." He also ruled out much of the ideas of Lamarckian inheritance present in Darwin's work, calling it "quite unnecessary." Darwin and Wallace would disagree on many substantive issues later in their lives especially, most bitterly on the question of whether human consciousness had itself evolved (to Darwin's horror, Wallace eventually turned against this and towards spiritualism).

Philosophical implications

According to Ernst Mayr, Darwin's evolutionary thinking rests on a rejection of essentialism, which assumes the existence of some perfect, essential form for any particular class of existent, and treats differences between individuals as imperfections or deviations away from the perfect essential form. Darwin embraced instead what Mayr calls " population thinking", which denies the existence of any essential form and holds that a class is the conceptualization of the numerous unique individuals. Individuals, in short, are real in an objective sense, while the class is an abstraction, an artifact of epistemology. This emphasis on the importance of individual differences is necessary if one believes that the mechanism of evolution, natural selection, operates on individual differences.

Mayr claims essentialism had dominated Western thinking for two thousand years, and that Darwin's theories thus represent an important and radical break from traditional Western philosophy. Ripples of Darwin's thought can now be seen in fields such as economics and complexity theory, suggesting that Darwin's influence extends well beyond the field of biology.

The historian of science Peter J. Bowler has suggested that many of the "implications" attributed to Darwinism had little to do with Darwin's theories themselves. Many of the so-called "Darwinists" of the late-nineteenth century, such as Herbert Spencer and Ernst Haeckel, were actually very non-Darwinian in many aspects of their thought and theory, and even the biggest supporters of Darwin, such as Thomas Henry Huxley, were suspicious as to whether natural selection was really what caused evolution. Nevertheless, Darwin became quickly identified with evolution in general and hailed as the figurehead of many conceptual changes in both science and society, whether or not all of these ideas were stated explicitly or at all in Darwin's work itself. (Bowler 1989)

The philosopher Daniel Dennett recapitulated those philosophical implications in his book Darwin's Dangerous Idea.