Richard O'Connor

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: World War II

| Sir Richard O'Connor | |

|---|---|

| August 21, 1889 to June 17, 1981 | |

|

|

| Place of birth | Srinagar, India |

| Place of death | London, United Kingdom |

| Allegiance | British Army |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | Western Desert Force XIII Corps VIII Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War I Operation Compass Operation Epsom Operation Jupiter Operation Goodwood Operation Bluecoat Operation Market Garden |

| Awards | KT, GCB, DSO, MC |

| Other work | Commandant of the Army Cadet Force, Scotland Colonel of the Cameronians Lord Lieutenant of Ross and Cromarty Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland |

General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, KT, GCB, DSO, MC, ADC ( 21 August 1889 - 17 June 1981) was a British Army general who commanded the Western Desert Force in the early years of World War II. He was the field commander for Operation Compass, in which his forces completely destroyed a much larger Italian army - a victory which nearly drove the Axis from Africa entirely, and in turn, led Adolf Hitler to send the Deutsches Afrikakorps under Erwin Rommel to try and reverse the situation. O'Connor was later captured and spent over two years in an Italian prisoner of war camp, but escaped and in 1944 commanded VIII Corps in Normandy and later during Operation Market Garden. In 1945 he was general officer in command of the Eastern Command in India, and then headed the North Western Army in the closing days of British rule in the subcontinent.

Though arguably one of the finest generals of WWII, O'Connor's modest, unassuming manner has caused historians to overlook him in favour of more flamboyant figures. His imprisonment during the conflict's truly decisive phases robbed him of many prime opportunities to prove his abilities further, and several of his peers and subordinates were promoted over him. Yet for demonstrating a dignity, courage and character which extended well beyond the battlefield, O'Connor was recognized with the highest level of knighthood in two different orders of chivalry. He was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, French Croix de guerre and Legion of Honour and served as Aide-de-camp to King George VI.

Early life and the First World War

O'Connor was born in Srinagar, Kashmir, India, on 21 August 1889. The son of a major in the Royal Irish Fusiliers, and the maternal grandson of a former Governor of India's central provinces, he was destined for an army career. Young Richard attended Tonbridge Castle School in 1899 and The Towers School in Crowthorne in 1902. In 1903, after his father's death in an accident, he transferred to Wellington School in Somerset. He attended the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in 1908.

In October of the following year he was billeted to the 2nd Battalion of the Cameronians. O'Connor would maintain close ties with the Regiment for the rest of his life. In January 1910, the battalion was posted to Colchester, where he received signals and rifle training. It was then stationed in Malta from 1911 to 1912 where O'Connor served as Regimental Signals Officer.

During World War I, O'Connor served as Signals Officer of 22 Brigade in the 7th Division and captain, in command of 7th Division's Signals Company and brevet brigade major in 91 Brigade, 7th Division. He was awarded the Military Cross in February 1915. In March of that year he saw action at Arras and Bullecourt. O'Connor was awarded the DSO and appointed brevet lieutenant-colonel in command of 1st Infantry Battalion of the Honourable Artillery Company, part of the 7th Division, in June 1917.

In November, the division was transferred to the Italian Front at the River Piave to assist the Italians against Austro-Hungarian forces. In late October 1918, O'Connor was directed to capture the island of Grave di Papadopoli on the Piave River. This mission was successfully accomplished by 2nd Battalion, and O'Connor was awarded the Italian Silver Medal of Honour along with a bar to add to his DSO.

Inter-War years

From 1920 to 1921 he attended the Staff College, Camberley. O'Connor's other service in the years between the world wars included an appointment (from 1921 to 1924) as brigade major of the Experimental Brigade (or 5 Brigade), which was formed to test methods and procedures for using tanks and aircraft in co-ordination with infantry and artillery. Many of the theories of mechanised, combined arms manoeuvre warfare put forth by J.F.C. Fuller (the brigade's commander), Liddell Hart, Heinz Guderian, and others at the time were being practiced by 5 Brigade.

He returned to his old unit, The Cameronians, as adjutant from 1924 to 1925. From 1925 to 1927 he served as a company commander at Sandhurst. He returned to the Staff College at Camberley as an instructor from 1927 to 1929. In 1930 O'Connor again served with the 1st Battalion of The Cameronians in Egypt and from 1931 to 1932 in Lucknow, India. From 1932 to 1934 he was a general staff officer, grade 2 at the War Office. He attended the Imperial Defence College, London in 1935. In October of that year, O'Connor, having been promoted brigadier, assumed command of the Peshawar Brigade in northwest India. He would later say the lessons he learned in mobility during this time would serve him well later in Libya. In September 1938, O'Connor was promoted to major-general and appointed Commander of the 7th Division in Palestine, along with the additional responsibility as Military Governor of Jerusalem. It was here he worked alongside Major-General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the 8th Division, to try to quell unrest between the Jewish and Arab communities. In August 1939, 7th Division was transferred to the fortress at Mersa Matruh, Egypt, where O'Connor was concerned with defending the area against a potential attack from the massed forces of the Italian Tenth Army over the border in Libya.

The Italian Offensive and Operation Compass

Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940. O'Connor was appointed Commander of the Western Desert Force, and tasked by General Wilson, commander of the Army of the Nile, to protect Egypt and the Suez Canal from Italian attack. To accomplish this, Wilson and O'Connor planned to use a screen of light tanks and armoured cars, supported by artillery, to delay the Italians led by Marshal Rodolfo Graziani. In command of this delaying force was Brigadier-General Gott. Meanwhile, the main force was to retreat towards Mersa Matruh and the Baggush Box where strong fixed defences had been prepared. These would stop the Italians long enough for reinforcements to arrive, bolster the defence and, eventually, launch a counteroffensive.

On 13 September, Graziani struck: his leading divisions advanced sixty miles into Egypt where they reached the town of Sidi Barrani and, short of supplies, began to dig in. O'Connor then began to prepare for a counterattack. He had the 7th Armoured Division and the Indian 4th Infantry Division, the two finest remaining divisions in the British Army following the Battle of Dunkirk, along with two brigades. In total he had around 36,000 men. The Italians had nearly five times as many troops along with hundreds more tanks and artillery pieces and supported by a much larger air force. The British, however, were better trained, better led, had (for the most part) better weapons and equipment and greater mobility. O'Connor intended to use all these advantages to the utmost. The preparations continued: a convoy was sent from Britain through the Mediterranean, risking attack from Axis forces, carrying valuable matériel to Egypt. Among the cargo were over 150 tanks, 100 artillery pieces and nearly 1,000 machine guns and anti-tank guns. Meanwhile, small raiding columns were sent out from the 7th Armoured and newly formed Long Range Desert Group to probe, harass, and disrupt the Italians (this marked the start of what became the SAS). The Royal Navy and Royal Air Force bombarded enemy strongpoints, airfields and rear areas. As a result, O'Connor, his adviser Brigadier Eric Dorman-Smith, and his men began to realise just how poorly led and ill-prepared their foes were, despite having a huge numerical advantage.

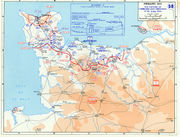

The counteroffensive, Operation Compass, began on 8 December 1940. What followed was a masterpiece of manoeuvre, concentration of forces, firepower, and combined arms.

O'Connor's relatively small force of 31,000 men, 275 tanks and 120 artillery pieces, ably supported by an RAF wing and the Royal Navy, ripped through a gap in the Italian defences at Sidi Barrani near the coast. The Desert Force cut a swath through the Italian rear areas, stitching its way between the desert and the coast, gobbling up strongpoint after strongpoint by cutting off and isolating each one. The Italian guns proved to be no match for the heavy British Matilda tanks and their shells bounced off the armour. By mid-December the Italians had been thrown completely out of Egypt, leaving behind 38,000 prisoners and large stores of equipment.

The Desert Force paused to rest briefly before continuing the assault into Italian Libya against the remainder of Graziani's disorganised army. At that point, the Commander-in-Chief Middle East General Sir Archibald Wavell ordered the 4th Indian Division withdrawn to spearhead the invasion of Italian East Africa. This veteran division was to be replaced by the inexperienced 6th Australian Division, which was unprepared for desert warfare. Despite this setback, the offensive continued with minimum delay, and by the end of December the 6th Australian besieged and took Bardia, which fell along with 40,000 more prisoners and 400 guns.

In January 1941, the Western Desert Force was redesignated XIII Corps directly answerable to General Wavell. O'Connor not only approved of this change but had suggested it earlier. On 9 January, the offensive resumed. By the 12th, the strategic fortress port of Tobruk was invested. On the 22nd it fell and another 25,000 Italian POWs were taken, as well as valuable supplies, food, and weapons. On January 26, the remaining Italian divisions in eastern Libya began to retreat to the northwest along the coast. O'Connor promptly moved to pursue and cut them off, sending the armour southwest through the desert in a wide flanking movement, while the infantry gave chase along the coast to the north. His armour caught up with the fleeing Italians at Beda Fomm on 5 February, blocking the main coast road and their route of escape. Two days later, after a costly and failed attempt to break through the blockade, and with the main British infantry force fast bearing down on them from Bengazi to the north, the demoralised, exhausted Italians unconditionally capitulated. O'Connor cabled back to Wavell, "Fox killed in the open..."

In two months, the XIII Corps/Western Desert Force had advanced over 800 miles (1,300 km), destroyed an entire Italian army of ten divisions, taken over 130,000 prisoners, 400 tanks and 1,292 guns at the cost of 500 killed and 1,373 wounded - a remarkable military achievement and a true British blitzkrieg. In recognition of this, O'Connor was made a Knight Commander of the Order of Bath, the first of his two knighthoods. When Wavell and others congratulated O'Connor on his impressive feat, he responded in his usual modest, unassuming manner, "I suppose one could characterise it as a complete victory."

The tide turns and capture

In a grand strategic sense, however, the victory of Operation Compass was not yet complete. O'Connor was fully aware of this and urged Wavell to allow him to push on to Tripoli with all due haste to finish off the Italians in North Africa. Wavell concurred, and XIII Corps resumed its advance. But O'Connor's new offensive would prove short-lived. When the Corps reached El Agheila, just to the southwest of Beda Fomm, Churchill ordered the advance to halt there. The Axis had invaded Greece and Wavell was ordered to send all available forces there as soon as possible to oppose this. Wavell had to take the 6th Australian Division, along with part of 7th Armoured Division and most of the supplies and air support, for this ultimately doomed operation. O'Connor was now forced to hold the line at El Agheila with a single understrength division, negligible air cover and over-extended supply lines.

But matters were soon to become much worse for the British. By March 1941, Hitler had dispatched General Erwin Rommel along with the Deutsches Afrikakorps to bolster the all but defeated Italians. Wavell and O'Connor now faced a formidable foe under a commander whose brilliance, resourcefulness, and daring would prove a worthy match. Rommel wasted little time in launching his own offensive and, by the end of March, had driven what was left of XIII Corps back from the El Agheila line, retaking Bengazi along with most of western Cyrenaica.

Justly alarmed by this sudden turn of events and with command responsibilities now stretching across the eastern Mediterranean, Wavell appointed Lieutenant-General Sir Philip Neame commander of British and Commonwealth troops in Egypt. Neame and O'Connor quickly formed a friendship, both preferring to command from the front lines rather than from a distant headquarters. The two while returning to safety after a night reconnaissance mission were captured by a German patrol on 7 April 1941, mostly due to Neame driving the wrong way.

O'Connor would spend the next two and a half years as a prisoner of war, mainly at the Castello di Vincigliata near Florence, Italy (a virtual Club Med for senior allied prisoners). Here he and Neame were in the distinguished and impressive company of such figures as Major-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart and Air Vice Marshal O.T. Boyd. Although the conditions of their imprisonment were not unpleasant, the officers soon formed an escape club and began planning a breakout. Their first attempt, a simple attempt to climb over the castle walls, resulted in a month's solitary confinement. The second attempt, by an escape tunnel built between October 1942 and March 1943, was initially successful. Boyd made it to Como near the Swiss border, but O'Connor and de Wiart were captured near Bologna in the Po Valley. It was only after the Italian surrender in September 1943 that the final, successful, escape was made with help from the Italian resistance movement while O'Connor was being transferred from Vincigliati. After a failed rendezvous with a submarine, he arrived by boat at Termoli, then went on to Bari where he was welcomed as a guest by General Alexander on 21 December 1943. In later life, he would remain in touch with his fellow prisoners from the Vincigliati escape club and with the members of the Italian resistance, who had aided him during his escape. Upon his return to Britain, O'Connor was presented with the knighthood he had been awarded in 1941 and promoted to lieutenant-general. Montgomery suggested that O'Connor be his successor as Eighth Army commander but that post was instead given to Oliver Leese and O'Connor was given a corps to command.

VIII Corps and Normandy

On 21 January 1944 O'Connor became commander of VIII Corps. It consisted of the Guards Armoured Division, 11th Armoured Division, 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division along with 6 Guards Tank Brigade, 8 Group Royal Artillery and 2 Household Cavalry Regiment. A powerful force, but one still in need of much training and preparation for the upcoming Operation Overlord. O'Connor proved more than up to the task, and over the following months the Corps would conduct many training operations in Yorkshire, including ones involving the new Sherman "Crab" mine-clearing flail tanks and testing of novel tank modifications (see Hobart's Funnies). During an inspection of the Guards division by Prime Minister Churchill in April, O'Connor raised concerns about armour protection and escape hatches on the Cromwell and Sherman tanks. These concerns would later prove to be well-founded. Churchill was impressed by O'Connor and the two would continue a correspondence.

On 11 June 1944, O'Connor and the leading elements of VIII Corps arrived in Normandy in the sector around Caen. Their first mission was to break out from the bridgehead established by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, cross the Odon and Orne rivers, then secure the high-ground positions northeast of Bretteville-sur-Laize and cut Caen off from the south. The breakout and river crossings were accomplished promptly. O'Connor's commanding officer (and friend from his days in Palestine) Montgomery, congratulated him and his Corps on their success. But cutting off Caen would prove much harder (see Operation Epsom). O'Connor raised concerns that the Germans might launch a counterattack, and strongly recommended the ground gained by VIII Corps be consolidated before continuing on further against Caen. This was ignored, however, and the Germans did exactly as O'Connor had feared. VIII Corps was pushed back over the Orne. O'Connor tried to re-establish a bridgehead ( Operation Jupiter), but met with little success.

The next major action for VIII Corps would be Operation Goodwood. The attack began on 18 July with a massive aerial bombardment by the 9th USAAF, and was ended on 20 July with a successful three-pronged drive to capture Bras and Hubert-Folie on the right, Fontenay on the left and Bourguebus Ridge in the centre. This was followed by Operation Bluecoat, formulated by O'Connor himself. 15th (Scottish) Division attacked towards Vire to the east and west of Bois du Homme in order to facilitate the American advance in Operation Cobra. A swift drive was followed by fierce fighting to the south during the first two days of the advance, with both sides taking heavy losses.

As the allies prepared to pursue the Germans from France, O'Connor learned that VIII Corps would not take part in this phase of the campaign. VIII Corps was placed in reserve, replaced by XII Corps under Lieutenant-General Neil Ritchie. His command was reduced in mid-August, with the transfer of 11th Armoured Division to XXX Corps and 15th (Scottish) Division to XII Corps. While in reserve, O'Connor maintained an active correspondence with Churchill, Montgomery and others, making suggestions for improvements for armoured vehicles and addressing various other problems such as combat fatigue. Some of his recommendations were followed up (such as for mounting "rams" on armoured vehicles in order to cope with the difficult hedgerow country), but most were ignored.

Operation Market Garden, India and afterwards

O'Connor remained in command of VIII Corps, for the time being, and was given the task of supporting Horrocks' XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden (the plan by Montgomery to establish a bridgehead in the Netherlands across the Rhine). In spite of having reduced forces and a largely thankless task, his Corps advanced and captured the Dutch towns of Deurne and Helmond. O'Connor suggested a possible string of operations in the following days, including the construction of bridges over the Escaut and the Meuse canal, and the capture of Soerendonk and Weert. Such actions, if taken, might have bypassed the main German defences which had bogged down XXX Corps, and could have salvaged Market Garden, saved thousands of lives and shortened the war in Europe by weeks or months. VIII Corps next took part in the advance to take Venray and Venlo beginning on 12 October.

In early September 1944, O'Connor heard rumours that he might be transferred to India. When he wrote to Montgomery about this, he was assured this was unlikely. On 27 November he received orders to take over from Lieutenant-General Sir Moseley Mayne as GOC-in-C, Eastern Army in India. This marked the end of a long and distinguished combat career. As was O'Connor's habit, he stayed in touch with members of VIII Corps after his transfer to India, and received with pride accounts of their advances.

In November 1945, O'Connor was promoted to full General and appointed GOC-in-C, North Western Army. In July 1946 he took over as Adjutant-General to the Forces and Aide De Camp General to the King. He spent much of this time visiting British troops stationed throughout India and the Far East. His career as Adjutant General was to be short-lived, however. After a disagreement over a cancelled demobilisation for troops stationed in the Far East, O'Connor offered his resignation in August 1947, which was accepted. Not long after this he was installed a Knight Grand Cross of the Bath.

O'Connor retired in 1948 at the age of fifty-eight. Despite this, he maintained his links with the Army and took on other responsibilities.

He was Commandant of the Army Cadet Force, Scotland from 1948 to 1959; Colonel of the Cameronians, 1951 to 1954; Lord Lieutenant of Ross and Cromarty from 1955 to 1964 and served as Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1964. His first wife, Jean, died in 1959. In 1963 he married Dorothy Russell. In July 1971 he was created Knight of the Thistle. He died in London on 17 June 1981.