Momentum

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: General Physics

In classical mechanics, momentum ( pl. momenta; SI unit kg m/s) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. For more accurate measures of momentum, see the section "modern definitions of momentum" on this page.

In general, the momentum of an object can be conceptually thought of as how difficult it is to stop the object, as determined by multiplying two factors: its inertia (the resistance of an object to being accelerated) and its velocity. As such, it is a natural consequence of Newton's first and second laws of motion. Having a lower speed or having less mass (how we measure inertia) results in having less momentum.

Momentum is a conserved quantity, meaning that the total momentum of any closed system (one not affected by external forces, and whose internal forces are not dissipative in nature) cannot be changed.

The concept of momentum in classical mechanics was originated by a number of great thinkers and experimentalists. René Descartes referred to mass times velocity as the fundamental force of motion. Galileo in his Two New Sciences used the term "impeto" (Italian), while Newton's Laws of Motion uses motus (Latin), which has been interpreted by subsequent scholars to mean momentum.

Momentum in Newtonian mechanics

If an object is moving in any reference frame, then it has momentum in that frame. It is important to note that momentum is frame dependent. That is, the same object may have a certain momentum in one frame of reference, but a different amount in another frame.

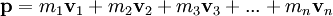

The amount of momentum that an object has depends on two physical quantities: the mass and the velocity of the moving object in the frame of reference. In physics, the symbol for momentum is usually denoted by a small bold p (bold because it is a vector); so this can be written:

where:

- p is the momentum

- m is the mass

- v the velocity

- m is the mass

(using bold text for vectors).

The origin of the use of p for momentum is unclear. It has been suggested that, since m had already been used for "mass", the p may be derived from the Latin petere ("to go") or from "progress" (a term used by Leibniz).

The velocity of an object at a particular instant is given by its speed and the direction of its motion at that instant. Because momentum depends on and includes the physical quantity of velocity, it too has a magnitude and a direction and is a vector quantity. For example the momentum of a 5-kg bowling ball would have to be described by the statement that it was moving westward at 2 m/s. It is insufficient to say that the ball has 10 kg m/s of momentum because momentum is not fully described unless its direction is given.

Momentum for a system

Relating to mass and velocity

The momentum of a system of objects is the vector sum of the momenta of all the individual objects in the system.

where

is the momentum

is the momentum- mi is the mass of object i

the velocity of object i

the velocity of object i is the number of objects in the system

is the number of objects in the system- mi is the mass of object i

Relating to force

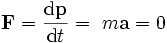

Force is equal to the rate of change of momentum:

.

.

In the case of constant mass, and velocities much less than the speed of light, this definition results in the equation  , commonly known as Newton's second law.

, commonly known as Newton's second law.

If a system is in equilibrium, then the change in momentum with respect to time is equal to 0:

Conservation of momentum

The principle of conservation of momentum states that the total momentum of a closed system of objects (which has no interactions with external agents) is constant. One of the consequences of this is that the centre of mass of any system of objects will always continue with the same velocity unless acted on by a force outside the system.

Conservation of momentum is a consequence of the homogeneity (shift symmetry) of space.

In an isolated system (one where external forces are absent) the total momentum will be constant: this is implied by Newton's first law of motion. Newton's third law of motion, the law of reciprocal actions, which dictates that the forces acting between systems are equal in magnitude, but opposite in sign, is due to the conservation of momentum.

Since momentum is a vector quantity it has direction. Thus, when a gun is fired, although overall movement has increased compared to before the shot was fired, the momentum of the bullet in one direction is equal in magnitude, but opposite in sign, to the momentum of the gun in the other direction. These then sum to zero which is equal to the zero momentum that was present before either the gun or the bullet was moving.

Conservation of momentum and collisions

Momentum has the special property that, in a closed system, it is always conserved, even in collisions. Kinetic energy, on the other hand, is not conserved in collisions if they are inelastic. Since momentum is conserved it can be used to calculate unknown velocities following a collision.

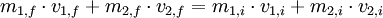

A common problem in physics that requires the use of this fact is the collision of two particles. Since momentum is always conserved, the sum of the momenta before the collision must equal the sum of the momenta after the collision:

where:

- u signifies vector velocity before the collision

- v signifies vector velocity after the collision.

Usually, we either only know the velocities before or after a collision and would like to also find out the opposite. Correctly solving this problem means you have to know what kind of collision took place. There are two basic kinds of collisions, both of which conserve momentum:

- Elastic collisions conserve kinetic energy as well as total momentum before and after collision.

- Inelastic collisions don't conserve kinetic energy, but total momentum before and after collision is conserved.

Elastic collisions

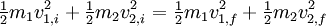

A collision between two pool or snooker balls is a good example of an almost totally elastic collision. In addition to momentum being conserved when the two balls collide, the sum of kinetic energy before a collision must equal the sum of kinetic energy after:

Since the 1/2 factor is common to all the terms, it can be taken out right away.

Head-on collision (1 dimensional)

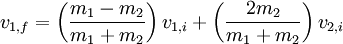

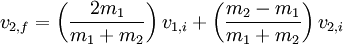

In the case of two objects colliding head on we find that the final velocity

which can then easily be rearranged to

Now consider if mass of one body say m1 is far more than m2 (m1>>m2). In that case m1+m2 is approximately equal to m1. And m1-m2 is approximately equal to m1.

Put these values in the above equation to calculate the value of v2 after collsion. The expression changes to v2 final is 2*v1-v2. Its physical interpretation is in case of collison between two body one of which is very heavy, the lighter body moves with twice the velocity of the heavier body less its actual velocity but in opposite direction.

Multi-dimensional collisions

In the case of objects colliding in more than one dimension, as in oblique collisions, the velocity is resolved into orthogonal components with one component perpendicular to the plane of collision and the other component or components in the plane of collision. The velocity components in the plane of collision remain unchanged, while the velocity perpendicular to the plane of collision is calculated in the same way as the one-dimensional case.

For example, in a two-dimensional collision, the momenta can be resolved into x and y components. We can then calculate each component separately, and combine them to produce a vector result. The magnitude of this vector is the final momentum of the isolated system.

See the elastic collision page for more details.

Inelastic collisions

A common example of a perfectly inelastic collision is when two snowballs collide and then stick together afterwards. This equation describes the conservation of momentum:

It can be shown that a perfectly inelastic collision is one in which the maximum amount of kinetic energy is converted into other forms. For instance, if both objects stick together after the collision and move with a final common velocity, one can always find a reference frame in which the objects are brought to rest by the collision and 100% of the kinetic energy is converted. This is true even in the relativistic case and utilized in particle accelerators to efficiently convert kinetic energy into new forms of mass-energy (i.e. to create massive particles).

See the inelastic collision page for more details.

Modern definitions of momentum

Momentum in relativistic mechanics

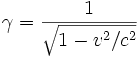

In relativistic mechanics, momentum is defined as:

where

- m is the invariant mass of the object moving,

is the Lorentz factor

is the Lorentz factor- v is the relative velocity between an object and an observer

- c is the speed of light.

Relativistic momentum becomes Newtonian momentum:  at low speed (v/c -> 0).

at low speed (v/c -> 0).

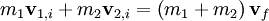

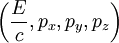

Relativistic four-momentum as proposed by Albert Einstein arises from the invariance of four-vectors under Lorentzian translation. The four-momentum is defined as:

where

- px is the x component of the relativistic momentum,

- E is the total energy of the system:

- E is the total energy of the system:

The "length" of the vector is the mass times the speed of light, which is invariant across all reference frames:

- (E / c)2 − p2 = (mc)2

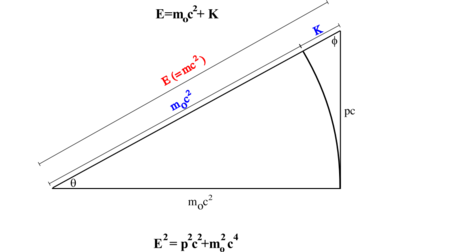

The diagram given alongside can serve as a useful mnemonic for remembering the above relations involving relativistic energy(E), invariant mass (m0), and relativistic momentum(p).

(Please note that in the notation used by the diagram's creator, the invariant mass m is subscripted with a zero, m0.)

Momentum of massless objects

Massless objects such as photons also carry momentum. The formula is:

where

- h is Planck's constant,

- λ is the wavelength of the photon,

- E is the energy the photon carries and

- c is the speed of light.

- λ is the wavelength of the photon,

Generalization of momentum

Momentum is the Noether charge of translational invariance. As such, even fields as well as other things can have momentum, not just particles. However, in curved space-time which is not asymptotically Minkowski, momentum isn't defined at all.

Momentum in quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics, momentum is defined as an operator on the wave function. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle defines limits on how accurately the momentum and position of a single observable system can be known at once. In quantum mechanics, position and momentum are conjugate variables.

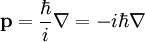

For a single particle with no electric charge and no spin, the momentum operator can be written in the position basis as

where:

is the gradient operator

is the gradient operator is the reduced Planck constant.

is the reduced Planck constant.

This is a commonly encountered form of the momentum operator, though not the most general one.

Momentum in electromagnetism

When electric and/or magnetic fields move, they carry momenta. Light (visible, UV, radio) is an electromagnetic wave and also has momentum. Even though photons (the particle aspect of light) have no mass, they still carry momentum. This leads to applications such as the solar sail.

Momentum is conserved in an electrodynamic system (it may change from momentum in the fields to mechanical momentum of moving parts). The treatment of the momentum of a field is usually accomplished by considering the so-called energy-momentum tensor and the change in time of the Poynting vector integrated over some volume. This is a tensor field which has components related to the energy density and the momentum density.

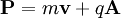

The definition canonical momentum corresponding to the momentum operator of quantum mechanics when it interacts with the electromagnetic field is, using the principle of least coupling:

,

,

instead of the customary

,

,

where:

is the electromagnetic vector potential

is the electromagnetic vector potential- m the charged particle's invariant mass

its velocity

its velocity- q its charge.

- m the charged particle's invariant mass

Figurative use

A process may be said to gain momentum. The terminology implies that it requires effort to start such a process, but that it is relatively easy to keep it going. Alternatively, the expression can be seen to reflect that the process is adding adherents, or general acceptance, and thus has more mass at the same velocity; hence, it gained momentum.