Mancala

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Games

Mancala is a family of board games played around the world, sometimes called sowing games or count and capture games, which comes from the general gameplay. The games of this family best known in the Western world are Oware, Kalah, Sungka and Omweso, and Bao. Mancala games play a role in many African and some Asian societies comparable to that of chess in the West.

Names

People unfamiliar with mancala games commonly assume there is a particular game with the name Mancala. This perception is helped by marketing which often fails to differentiate variations or gives names like "Ethiopian" or "Nigerian". Although these countries traditionally play the game, there exist several different ways of playing it even within those cultures. As such, these names are not wholly descriptive. Even names which are rightly associated with certain games, such as "Awari", are frequently lifted and applied to different games.

In fact, the name mancala is the Arab name commonly given to some games of this type; the word comes from the Arabic word naqala (literally "to move"). This word is used at least in Syria, Lebanon and Egypt, but is not consistently applied to any one game. In the Western world, "mancala" is often seen used as a generic name for the game "kalah". Research in English refers to "games in the mancala family" or "mancala games", rather than "mancala variants" which would imply there is one main mancala game on which the others are based.

Adding to the confusion, widespread mancala games may go by different names in different regions, often with slight rules variations. Then, there are groups that give multiple games the same name; sometimes one is intended to be played by men, another by women. Historically, researchers have had difficulty separating the rules for games apart from strategic implications or favored setups, which has caused additional confusion over which games are distinct, or which names refer to the same game. Because of these considerations, and the fact that mancala games have reached the West from these multiple cultures, it is difficult to establish what names and rules, if any, are the "proper" ones.

The names of individual games often come from the equipment used; for instance, bao is the Swahili word meaning "board".

A variant called pallanguzhi is played in Tamil Nadu. The Yoruba people of West Africa call it "Ayo". In Ethiopia, where the game is thought to have originated, it is called "Gebeta" ( Ge'ez ገበጣ gebeṭā).

General gameplay

Mancala games share a general gameplay sequence of picking up all seeds from a hole (the strategy), then sowing seeds one at a time from a hole, and capturing based on the state of board. This leads to the English phrase "Count and Capture" sometimes used to describe the gameplay. Although the details differ greatly, this general sequence applies to all games.

Equipment

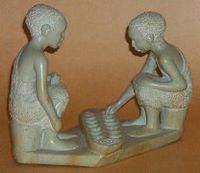

Equipment is typically a board, constructed of various materials, with a series of holes arranged in rows, usually two or four. Some games are more often played with holes dug in the earth, or carved in stone. The holes may be referred to as "depressions", "pits", or "houses". Sometimes, large holes on the ends of the board, called stores, are used for holding captured pieces. Playing pieces are seeds, beans, stones, or other small undifferentiated counters that are placed in and transferred about the holes during play. Nickernuts are one common example of pieces used. Board configurations vary among different games but also within variations of a given game; for example Endodoi is played on boards from 2 × 6 to 2 × 10.

With a two-rank board, players usually are considered to control their respective sides of the board, although moves often are made into the opponent's side. With a four-rank board, players control an inner row and an outer row, and a player's seeds will remain in these closest two rows unless the opponent captures them.

These games are good for getting children interacting and used to counting. Children can even be encouraged to make the game themselves as follows: Take two half dozen egg cartons, tear the tops off them both, and arrange them in a long line (lid, base, base, lid). You can staple or tape them together if you wish, and you can use pebbles or beads as seeds.

Object

The object of mancala games is usually to capture more seeds than the opponent; sometimes, one seeks to leave the opponent with no legal move in order to win.

Sowing

At the beginning of a player's turn, they select a hole with seeds that will be sown around the board. This selection is often limited to holes on the current player's side of the board, as well as holes with a certain minimum number of seeds.

In a process known as sowing, all the seeds from a hole are dropped one-by-one into subsequent holes in a motion wrapping around the board. Sowing is an apt name for this activity, since not only are many games traditionally played with seeds, but placing seeds one at a time in different holes reflects the physical act of sowing. If the sowing action stops after dropping the last seed, the game is considered a single lap game.

Multiple laps or relay sowing is a frequent feature of mancala games, although not universal. When relay sowing, if the last seed during sowing lands in an occupied hole, all the contents of that hole, including the last sown seed, are immediately resown from the hole. The process usually continues until sowing ends in an empty hole.

Many games from the Indian subcontinent use pussa-kanawa laps. These are like standard multilaps, but instead of continuing the movement with the contents of the last hole filled, a player continues with the next hole. A pussa-kanawa lap move will then end when a lap ends just prior to an empty hole.

Capturing

Depending on the last hole sown in a lap, a player may capture seeds from the board. The exact requirements for capture, as well as what is done with captured seeds, vary considerably among games. Typically, a capture requires sowing to end in a hole with a certain number of seeds, or ending across the board from seeds in specific configurations.

Another common way of capturing is to capture the contents of the holes that reach a certain number of seeds at any moment.

Also, several games include the notion of capturing holes, and thus all seeds sown on a captured hole belong at the end of the game to the player who captured it.

History

The history of mancala is unclear. The first evidence of the game is the fragment of a pottery board and several rock cuts found in Aksumite Ethiopia in Matara (now in Eritrea) and Yeha (in Ethiopia), which are dated by archaeologists to between the 6th and 7th century AD; the game may have been mentioned in the 14th century Ge'ez text "Mysteries of Heaven and Earth." The similarity of some aspects of the game to agricultural activity and the absence of a need for specialized equipment present the intriguing possibility that it could date to the beginnings of civilization itself; however, there is little verifiable evidence that the game is older than about 1300 years. Some purported evidence comes from the Kurna temple graffiti in Egypt, as reported by Parker in 1909 and Murray in his "Board games other than chess". However, accurate dating of this graffiti seems to be unavailable, and what designs have been found by modern scholars generally resemble games common to the Roman world, rather than anything like Mancala.

Although the games existed in pockets in Europe -- it is recorded as being played as early as the 17th century by merchants in England -- it has never gained much popularity in most regions, except in the Baltic area, where once it was a very popular game ("Bohnenspiel") and Bosnia, where it is called Ban-Ban and still played today. Mancala has also been found in Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece ("Mandoli", Cyclades) and in a remote castle in southern Germany (Schloss Weikersheim).

The USA has a larger mancala playing population, although many of these players are descendants of enslaved Africans. A traditional mancala game called Warra was still played in Louisiana in the early 20th century. Perhaps the unfamiliarity with mancala games in the West is in part due to historic prejudice against primitives; the assumption being that these games could not require any serious mental skill. The 1961 edition of Goren's Hoyle, which itself ascribes an Arab origin to the games, perhaps expresses a common sentiment upon discovery of the games' depth:

- The anthropologists have not undertaken to explain how it happens that the universal game of primitive peoples is one of pure intellectual skill. Mancala is wholly mathematical, akin to the game of drawing pebbles from a pile in an endeavor to win the last, but so complex as to remain a real contest.

Analysis

Sowing games can be analyzed using combinatorial game theory: see Jeff Erickson's article "Sowing Games". Even on slow hardware, computer programs can easily defeat strong human players.