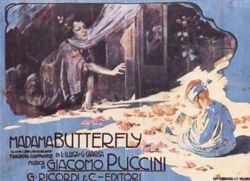

Madama Butterfly

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Poetry & Opera

Madama Butterfly (Madame Butterfly) is an opera in three acts (originally two acts) by Giacomo Puccini, with an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. The opera was based partly on a short story by John Luther Long, which was turned into a play by David Belasco; it was also based on the novel, Madame Chrysanthème (1887), by Pierre Loti.

The first version of the opera premiered February 17, 1904 at La Scala in Milan. It consisted of two acts and was very poorly received. On May 28 of that year, a revised version was released in Brescia. The revision split the disproportionately long second act in two, and included some other minor changes. In its new form Puccini's opera was a huge success; it crossed the Atlantic to the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1907. Today, the opera is enjoyed in two acts in Italy, while in America the three-act version is more popular. In fact, according to Opera America, Madama Butterfly is the most often-performed opera in North America.

The opera belongs essentially to the city of Nagasaki, and according to American scholar Arthur Groos was based on events that actually occurred there in the early 1890s. Japan's best-known opera singer Miura Tamaki won international fame for her perfomances as Cio-Cio-san and her statue, together with that of Puccini, can be found in Nagasaki's Glover Garden.

Roles

| Prima, February 17, 1904 ( Cleofonte Campanini) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Cio-Cio-San (Madame Butterfly) | soprano | Rosina Storchio |

| Suzuki, her maid | mezzo-soprano | Giuseppina Giaconia |

| B. F. Pinkerton, Lieutenant in the United States Navy | tenor | Giovanni Zenatello |

| Sharpless, United States consul at Nagasaki | baritone | Giuseppe de Luca |

| Goro, a marriage broker | tenor | |

| Prince Yamadori | baritone | |

| The Bonze, Cio-Cio-San's uncle | bass | |

| Yakuside, Cio-Cio-San's uncle | bass | |

| The Imperial Commissioner | bass | |

| The Official Registrar | bass | |

| Cio-Cio-San's mother | mezzo-soprano | |

| The aunt | soprano | |

| The cousin | soprano | |

| Kate Pinkerton | mezzo-soprano | |

| Dolore ('Sorrow'), Cio-Cio-San's child | silent | |

| Cio-Cio-San's relations and friends and servants | ||

Synopsis (final version)

:Time: 1904.

- Place: Nagasaki, Japan.

Act I

In the first act Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton, a sailor with the USS Abraham Lincoln in the port of Nagasaki marries Cio-Cio-San [tʃotʃosan], or what her friends call her "Butterfly," a 15-year-old Japanese geisha. The Matchmaker Goro has arranged the wedding contract and rented a little hillside house for the newlyweds. The American consul Sharpless, a kind man, begs Pinkerton to forego this plan, when he learns that Butterfly innocently believes the marriage to be binding. (In fact, Pinkerton may revoke the contract whenever he tires of the "marriage.") The lieutenant laughs at Sharpless's concern, and the bride appears with her geisha friends, joyous and smiling. Sharpless learns that, to show her trust in Pinkerton, she has renounced the faith of her ancestors and so she can never return to her own people. (Butterfly: "Hear what I would tell you.") Pinkerton also learns that she is the daughter of a disgraced samurai who committed seppuku, and so the little girl was sold to be trained as a geisha. The marriage contract is signed and the guests are drinking a toast to the young couple when the bonze, a Buddhist monk, (uncle of Cio-Cio-San, and presumably having entered the monastery in disgrace after the father's seppuku) enters, uttering imprecations against her for having taken to the foreign faith, and induces her friends and relatives to abandon her. Pinkerton, annoyed, hurries the guests off, and they depart in anger. With loving words he consoles the weeping bride, and the two begin their new life happily. (Duet, Pinkerton, Butterfly: "Just like a little squirrel"; Butterfly: "But now, beloved, you are the world"; "Ah! Night of rapture.")

Act II

Pinkerton's tour of duty is over, and he has returned to the United States, after promising Butterfly to return "When the robins nest again." Three years have passed. Butterfly's faithful servant Suzuki rightly suspects that he has abandoned them, but is upbraided for want of faith by her trusting mistress. (Butterfly: "Weeping? and why?") Meanwhile, Sharpless has been sent by Pinkerton with a letter telling Butterfly that he has married an American wife. Butterfly (who cannot read English) is enraptured by the sight of her lover's letter and cannot conceive that it contains anything but an expression of his love. Seeing Butterfly's joy, Sharpless cannot bear to hurt her with the truth. When Goro brings Prince Yamadori, a rich suitor, to meet Butterfly, she refuses to consider his suit, telling them with great offense that she is already married to Pinkerton. Goro explains that a wife abandoned is a wife divorced, but Butterfly declares defiantly, "That may be Japanese custom, but I am now an American woman." Sharpless cannot move her, and at last, as if to settle all doubt, Butterfly proudly presents her fair-haired child. "Can my husband forget this?" she challenges. Butterfly explains that the boy's name is "Trouble," but when when his father returns, his name will be "Joy." The consul departs sadly. But Butterfly has long been a subject of gossip, and Suzuki catches the duplicitous Goro spreading more. Just as things cannot seem worse, distant guns salute the new arrival of a man-of-war, the Abraham Lincoln, Pinkerton's ship. Butterfly and Suzuki, in great excitement, deck the house with flowers, and array themselves and the child in gala dress. All three peer through shoji doors to watch for Pinkerton's coming. As night falls, a long orchestral passage with choral humming (the "humming chorus") plays. Suzuki and the child gradually fall asleep - but Butterfly, alert and sleepless, never stirs.

Act III

Act three opens at dawn with Butterfly still intently watching. Suzuki awakens and brings the baby to her. (Butterfly: "Sweet, thou art sleeping.") Suzuki persuades the exhausted Butterfly to rest. Pinkerton and Sharpless arrive and tell Suzuki the terrible truth: Pinkerton has abandoned Butterfly for an American wife named Kate. The lieutenant is stricken with guilt and shame (Pinkerton: "Oh, the bitter fragrance of these flowers!"), but is too much of a coward to tell Butterfly himself. He has assigned this awful task to his wife, Kate. Suzuki, at first violently angry, is finally persuaded to listen as Sharpless assures her that Mrs. Pinkerton will care for the child if Butterfly will give him up. Pinkerton departs. Suzuki brings Butterfly into the room. She is radiant, expecting to find her husband, but is confronted instead by Pinkerton's new wife. As Sharpless watches silently, Kate begs Butterfly's forgiveness and promises to care for her child if she will surrender him to Pinkerton. Butterfly receives the truth with apathetic calmness, politely congratulates her replacement, and asks Kate to tell her husband that in he must come in half an hour, and then he may have Trouble, whoes name will then be changed to Joy. She herself will "find peace." She bows her visitors out, and is left alone with young Trouble. She bids a pathetic farewell to her child (Finale, Butterfly: "You, O beloved idol!"), blindfolds him, and puts a doll and small American flag in his hands. She takes her father's dagger--the weapon with which he made his suicide--and reads its inscription: "To die with honour, when one can no longer live with honour." She takes the sword and a white scarf behind a screen, and emerges a moment later with the scarf wrapped round her throat. She embraces her child for the last time and sinks to the floor. Pinkerton and Sharpless rush in and discover the dying girl. The lieutant cries out Butterfly's name in anguish as the curtain falls.

Noted arias and duets

- Quanto cielo! Quanto mar! (Entrance of Butterfly; (sung by Butterfly and the chorus)

- Viene la sera (Evening is falling; (sung by Butterfly and Pinkerton)

- Un bel dì vedremo (One fine day we shall see; (sung by Butterfly)

- Addio, fiorito asil (Adieu, flowered refuge; (sung by Pinkerton)

- Con onor muore (Death of Butterfly - She dies with honour) (sung by Butterfly)

Adaptations

- 1915: The opera was made into a film. It was directed by Sidney Olcott and starred Mary Pickford.

- 1922: Another film, The Toll of the Sea, based on the opera/play was released. This movie, which starred Anna May Wong, moved the story to China. It was also the first two-strip Technicolor motion picture ever released.

- 1984: British Pop impresario Malcolm McLaren wrote and performed a UK hit single, 'Madame Butterfly (Un Bel Di Vedremo)', produced by Stephen Hague, based on the opera and featuring the famous aria.

- 1988: In David Henry Hwang's play M. Butterfly, about a story of a French diplomat and a Chinese opera singer, Butterfly is denounced as a western stereotype of a timid, submissive Asian.

- 1989: The Broadway and West End musical Miss Saigon was, in part, based on Madama Butterfly. The story was moved to Vietnam and Thailand and set against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and the Fall of Saigon.

- 1995: Frédéric Mitterrand directed a film version of the opera in Tunisia, North Africa, starring Chinese opera singer Ying Huang.

- 1996: The Album Pinkerton by the rock band Weezer was based loosely on the opera.

- 2001: Aria by Pjotr Sapegin, an animated short inspired by the opera, awarded as best animated short by Tickleboots best online videos 2006 and Best short film Norway 2002, won Grand Prix in Odense International Film Festival 2002 and won the audience award in Århus Film Festival 2002.

- 2004: On the 100th anniversary of Madama Butterfly, Shigeaki Saegusa composed Jr. Butterfly to a libretto by Masahiko Shimada.

Criticisms

Since the 1990s, many have criticized or analyzed Madama Butterfly as part of a colonialist project of creating images of Asia. These critics posit that it presents a "feminized" view of Asia in the form of Cio-Cio, and one that in the end of the play is discarded and inferior. One example of this critique is the postmodernist version M. Butterfly, by David Henry Hwang. Many Asians and Asian-Americans resent the passive and tragic stereotyping of Asians, and view it as part of a larger racist/colonialist mentality prevalent when the opera was written.

Other critiques centre on the supposedly anti-American tone of the play, written by an Italian and presented mostly for European audiences. These critics claim that the historical basis for the American character was likely a French doctor or Scottish engineer, and that the intention of making him an "arrogant" American had more to do with Europe's anti-U.S. sentiment in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish-American War in 1898. Furthermore, Japan in 1904 was not a colony of any country, including the U.S., and, on the contrary, had defeated Russia in the same year in the Russo-Japanese War. Therefore the image of a colonialist America and a weak, passive Japan was possibly a projection of other Western/Asian relationships (e.g., Britain in China) on two third parties. Additionally, anti-American sentiment in Europe at the time was radically different from the more modern flavours: America was still seen as an extension of Europe proper, but in a junior sense, as the imperialist actions of the United States back then were minor when compared with the large-scale conquest and exploitation of Asia and Africa by European nations.

Both of these critiques fit into the larger view that the play presents ignorant stereotypes of foreign lands, and has more to do with idealized and romanticized images than with reality. The play also categorizes the world into polarities, Occidental and Oriental. Following these interpretations, the coincidence of the play and the rise of European colonialism were not unrelated.

In contrast, one may consider that in 1904 the general opinion of Europeans was that both the United States and Japan were upstart powers with colonial aspirations.