Kīlauea

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Central & South American Geography

| Kīlauea | |

|---|---|

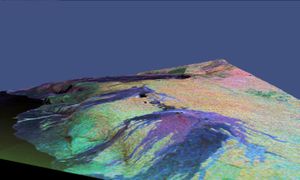

3D false-colour satellite image of Kīlauea |

|

| Elevation | 4,091 ft (1,247 m) |

| Location | Hawaiʻi, USA |

| Range | Hawaiian Islands |

| Coordinates | |

| Type | Shield volcano |

| Age of rock | < 23000 yrs |

| Last eruption | 2006 (continuing) |

Kīlauea is an active volcano in the Hawaiian Islands, one of five shield volcanoes that together form the Island of Hawaiʻi. In Hawaiian, the word kīlauea means "spewing" or "much spreading", in reference to the mountain's frequent outpouring of lava. It is presently the most active volcano and one of the most visited active volcanoes on the planet. Kīlauea is just the most recent of a long series of volcanoes that created the Hawaiian Archipelago, as the Pacific Plate moves over a more or less fixed hotspot in the Earth's mantle (see, however, Lōʻihi).

Description

Kīlauea's absolute location is 19.452 North, 155.292 West. It lies against the southeast flank of much larger Mauna Loa volcano. Mauna Loa's massive size and elevation (13,677 feet or 4,169 m) is a stark contrast to Kīlauea, which rises only 4,091 feet (1,247 m) above sea level, and thus from the summit caldera appears as a broad shelf of uplands well beneath the long profile of occasionally snow-capped Mauna Loa, 15 miles (24 km) distant.

First-time visitors to Kīlauea, not familiar with how different the profile of a shield volcano can be compared with stratovolcanoes like Mt. Fuji, Mount Hood, and Mount St. Helens, are usually unaware they are approaching the summit of an active volcano as they make the drive up through the cloud forest on State Rte. 11 to Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park from Hilo—or coming from Kailua-Kona via South Point across the Kaʻū Desert. From Hilo, the highway heads south to Keaʻau, then turns abruptly westward to begin the climb to the Kīlauea caldera. For some 20 miles (32 km) the road runs relatively straight, making a 4,000 ft (1,200 m) ascent. However, most of this climb is actually on the heavily vegetated flank of Mauna Loa; the crossing onto lava flows issued from Kīlauea is about 1 mile west of Glenwood, 18 miles (29 km) from Hilo. The Mauna Loa flows are several thousand years old; the lightly vegetated Kīlauea flows are only 350 to 500 years old.

Driving from the Kona Coast, the immense size of the Big Island becomes apparent: from Kailua-Kona it is 98 miles (158 km) on the Māmalahoa Highway (State Rte. 11) to Kīlauea. After passing around the southern end of Mauna Loa, the highway turns northeastward towards Kīlauea once past the town of Nāʻālehu. Yet, as from the Hilo side, the long climb from near sea level to the summit is all on the flank of Mauna Loa. Not until the Sulfur Bank scarp (the northwestern edge of Kīlauea Caldera), near the intersection of Crater Rim Drive in Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, does the road cross over onto Kīlauea. However, the highway parallels the line of contact between the two volcanoes—always less than 1 mile to the southeast—from the vicinity of Punaluʻu at the coast to the caldera at the summit.

Kaʻū

The highway route from the west (State Rte. 11) is vastly different from that seen when coming from Hilo. The highway approaches Kīlauea through a desert on the leeward slope called Kaʻū. Kīlauea's height of 4000 ft is sufficient to force most of the moisture out of the impinging Northeast Trades, leaving Kaʻū in the rain shadow of the "low" mountain. This area is also the very active southwest rift zone of Kīlauea, a prolific ash producer. Winds redistribute the ash, causing dust storms and forming dunes across a landscape barren of most vegetation.

Kīlauea Caldera and Halemaʻumaʻu Crater

Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park encompasses a portion of Kīlauea, and the park visitor centre is located near the margin of the summit caldera, overlooking a large pit crater called Halemaʻumaʻu. The roughly circular caldera measures 3x5 km (or 6x6 km, including the outermost ring faults).

Kīlauea eruptions

Eruptions at Kīlauea occur primarily either from the summit caldera or along either of the lengthy East and Southwest rift zones that extend from the caldera to the sea. In recent decades, eruptions have been continuous, with many of the lava flows reaching to the Pacific Ocean shore. About 90% of the surface of Kīlauea is lava flows less than 1,100 years old; 70% of the surface is younger than 600 years.

There were forty-five separate eruptions of Kīlauea in the twentieth century. The Mauna Ulu eruption of Kīlauea began on May 24, 1969 and ended on July 22, 1974. At the time, Mauna Ulu was the longest flank eruption of any Hawaiian volcano in recorded history. The eruption created a new vent, covered massive amounts of land with lava, and added new land to the island.

The Mauna Ulu eruption first started as a fissure between two pit craters, ʻĀloʻi and ʻAlae, where the Mauna Ulu shield would eventually form. Both pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā lava erupted from the volcano. Early on, fountains of lava burst out as much as 540 meters high. In early 1973, an earthquake occurred that caused Kīlauea to stop erupting near the original Mauna Ulu site and instead erupt near the craters Pauahi and Hiʻiaka. However, the eruption site soon returned to normal.

The current Kīlauea eruption began in January 1983 along the East rift zone from Puʻu ʻŌʻō-Kūpaʻianahā and continues to produce lava flows that travel 11 to 12 km from these vents to the sea. This eruption has covered over 104 km² of land on the southern flank of Kīlauea and has built out into the sea 2 km² of new land. Since 1983 more than 1.9 km³ of lava has been erupted, making the 1983-to-present eruption the largest historically known for Kīlauea. In fact in the early to middle 1980s Kīlauea was known as "The Drive-by Volcano" because anyone could ride by and see the lava fountains (some as much as 1000 feet in the air) from their car. The lava fountains are a great backdrop in the movie "Black Widow" made in 1985.

The 1990 lava flow in particular was notable for being destructive of property. In the 1990 lava flow the towns of Kalapana and Kaimū were totally destroyed, as were Kaimū Bay, Kalapana Black Sand Beach, and a large section of State Rte. 130, which now abruptly dead-ends at the lava flow.

While Kīlauea is justly known for its largely non-explosive eruptions, it has a darker side to it: it has had large explosive eruptions in the past . The most recent of such explosive eruptions occurred in 1924, when magma interacted with groundwater as the long-standing lava lake in Halemaʻumaʻu Crater drained. Even larger ones have occurred, including one in 1790, which killed at least several dozen people. Eruption columns are inferred to have gone at least as high as 9 km (5.6 miles) and even up to 15-20 km (9-12 miles) in altitude — much higher than the cruising altitude of airliners.

Eruptions from Kīlauea also are known for creating vog, or volcanic smog, which affects many areas of the Hawaiian Islands, including Oʻahu and Honolulu whenever winds come out of the south or southeast.

Pele

Kīlauea is considered to be the present home of Pele, the volcano goddess of ancient Hawaiian legend. Several special lava formations are named after her, including Pele's Tears (small droplets of lava that cool in the air and retain their teardrop shapes) and Pele's Hair (thin, brittle strands of volcanic glass that often form during the explosions that accompany a lava flow as it enters the ocean).

In Hawaiian mythology, Kīlauea is the location around where most of the conflict between Pele and the rain god Kamapuaʻa took place. Halemaʻumaʻu, "House of the ʻamaʻumaʻu fern", derives its name from the final struggle between the two gods: being the favorite residence of Pele, Kamapuaʻa, hard-pressed by Pele's ability to make lava spout from the ground at will, covered it with the fronds of the fern. Choking from the smoke which could not escape anymore, Pele emerged. Realizing that each could threaten the other with destruction, the gods had to call their fight a draw and divided the island among them: Kamapuaʻa received the windward northeastern side, and Pele ruled over the drier Kona (" leeward") side. The rusty, singed appearance of the young fronds of the ʻamaʻumaʻu was said to be a product of the legendary struggle.