Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Recent History

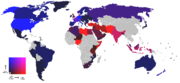

The Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy began after twelve editorial cartoons, most of which depicted the Islamic prophet Muhammad, were published in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten on 2005- 09-30. The newspaper explained that this publication was a contribution to debate regarding criticism of Islam and self-censorship. In response, Danish Muslim organizations held public protests and spread knowledge of Jyllands-Posten's publication. As the controversy grew, examples of the cartoons were reprinted in newspapers in more than fifty other countries, which led to violent as well as peaceful protests, including rioting particularly in the Muslim world.

Critics of the cartoons describe them as Islamophobic and/or argue that they are blasphemous to people of the Muslim faith, intended to humiliate a marginalized Danish minority, and that they are a manifestation of ignorance about the history of western imperialism, from colonialism to the current conflicts in the Middle East.

Supporters of the cartoons claim they illustrate an important issue in a period of Islamic extremist terrorism and that their publication is a legitimate exercise of the right of free speech. They also claim that similar cartoons about other religions are frequently printed, arguing that the followers of Islam were not targeted in a discriminatory way.

Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen described the controversy as Denmark's worst international crisis since World War II.

Descriptions of the drawings

Some of the cartoons can be difficult to fully understand for those without knowledge of certain Danish language metaphors or awareness of individuals of note to the Danish public. Furthermore, certain cartoons have captions written in Danish and one in Persian. Detailed descriptions of the cartoons and translations of the captions as well as explanations concerning Danish cultural references are provided here.

Timeline

| Jyllands-Posten cartoons controversy |

|

Events and reactions

Primary parties involved

|

Debate about self-censorship

On September 17, 2005, the Danish newspaper Politiken ran an article under the headline "Dyb angst for kritik af islam" ("Profound fear of criticism of Islam"). The article discussed the difficulty encountered by the writer Kåre Bluitgen, who was initially unable to find an illustrator who was prepared to work with Bluitgen on his children's book Koranen og profeten Muhammeds liv (English: The Qur'an and the life of the Prophet Muhammad ISBN 87-638-0049-7). Three artists declined Bluitgen's proposal before an artist agreed to assist anonymously. According to Bluitgen:

One [artist declined], with reference to the murder in Amsterdam of the film director Theo van Gogh, while another [declined, citing the attack on] the lecturer at the Carsten Niebuhr Institute in Copenhagen.

In October 2004, a lecturer at the Niebuhr institute at the University of Copenhagen was assaulted by five assailants who opposed his reading the Qur'an to non-Muslims during a lecture.

The refusal of the first three artists to participate was seen as evidence of self-censorship and led to much debate in Denmark, with other examples for similar reasons soon emerging. Comedian Frank Hvam declared that he would (hypothetically) dare urinating on the Bible on television, but not on the Qur'an while the translators of an essay collection critical of Islam also wished to remain anonymous due to concerns about violent reprisals.

Publication of the cartoons

On September 30, 2005, the daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten ("The Jutland Post") published an article entitled "Muhammeds ansigt" ("The face of Muhammad"). The article consisted of twelve cartoons (of which only some depicted Muhammad) and an explanatory text, in which Flemming Rose, Jyllands-Posten's culture editor, commented:

The modern, secular society is rejected by some Muslims. They demand a special position, insisting on special consideration of their own religious feelings. It is incompatible with contemporary democracy and freedom of speech, where you must be ready to put up with insults, mockery and ridicule. It is certainly not always attractive and nice to look at, and it does not mean that religious feelings should be made fun of at any price, but that is of minor importance in the present context. [...] we are on our way to a slippery slope where no-one can tell how the self-censorship will end. That is why Morgenavisen Jyllands-Posten has invited members of the Danish editorial cartoonists union to draw Muhammad as they see him. [...]

After the invitation from Jyllands-Posten to around forty different artists to give their interpretation of Muhammad, twelve caricaturists chose to respond with a drawing each. Many also commented on the surrounding self-censorship debate. Three of these twelve cartoons were illustrated by Jyllands-Posten's own staff, including the "bomb" and "niqaab" cartoons.

On February 19, Rose explained his intent further In the Washington Post:

The cartoonists treated Islam the same way they treat Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and other religions. And by treating Muslims in Denmark as equals they made a point: We are integrating you into the Danish tradition of satire because you are part of our society, not strangers. The cartoons are including, rather than excluding, Muslims.

In October 2005, the Danish daily Politiken polled thirty-one of the forty-three members of the Danish cartoonist association. Twenty-three said they would be willing to draw Muhammad. One had doubts, one refused because of fear of possible reprisals and six cartoonists refused to make the drawings because they respected the Muslim ban on depicting the prophet. Fifteen of the thirty-one cartoonists rejected Jyllands-Posten's project.

Danish Prime Minister's meeting refusal

Having received petitions from Danish imams, eleven ambassadors from Muslim-majority counties asked for a meeting with Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen in 12 October 2005, in order to discuss what they perceived as an "on-going smearing campaign in Danish public circles and media against Islam and Muslims". In a letter the ambassadors mentioned not only the issue of the Muhammad cartoons, but also a recent indictment against Radio Holger, and statements by MP Louise Frevert and the Minister of Culture Brian Mikkelsen. It concluded:

We deplore these statements and publications and urge Your Excellency’s government to take all those responsible to task under law of the land in the interest of inter-faith harmony, better integration and Denmark's overall relations with the Muslim world.

The government answered the ambassadors' request for a meeting with Rasmussen with a letter only: "The freedom of expression has a wide scope and the Danish government has no means of influencing the press. However, Danish legislation prohibits acts or expressions of blasphemous or discriminatory nature. The offended party may bring such acts or expressions to court, and it is for the courts to decide in individual cases."

The ambassadors maintained that they had never asked for Jyllands-Posten to be prosecuted; possibly, the non-technical phrase of the letter, "to take NN to task under law", meant something like "to hold NN responsible within the limits of the law". Rasmussen replied: "Even a non-judicial intervention against Jyllands-Posten would be impossible within our system".

The Egypt Minister of Foreign Affairs, Aboul Gheit, wrote several letters to the Prime Minister of Denmark and to the United Nations Secretary-General explaining that they did not want the Prime Minister to prosecute Jyllands-Posten; they only wanted "an official Danish statement underlining the need for and the obligation of respecting all religions and desisting from offending their devotees to prevent an escalation which would have serious and far-reaching consequences". Subsequently, the Egyptian government played a leading role in defusing the issue in the Middle East.

The refusal to meet the ambassadors has been criticized by the opposition, twenty-two Danish ex-ambassadors, and ex-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Uffe Ellemann-Jensen.

Judicial investigation of Jyllands-Posten

On October 27, 2005, a number of Muslim organizations filed a complaint with the Danish police claiming that Jyllands-Posten had committed an offence under section 140 and 266b of the Danish Criminal Code.

- Section 140 of the Criminal Code, known as the blasphemy law, prohibits disturbing public order by publicly ridiculing or insulting the dogmas of worship of any lawfully existing religious community in Denmark. Only one case has ever resulted in a sentence, a 1938 case involving an anti-Semitic group. The most recent case was in 1971 when a program director of Danmarks Radio was charged, but found not guilty.

- Section 266b criminalises insult, threat or degradation of natural persons, by publicly and with malice attacking their race, colour of skin, national or ethnical roots, faith or sexual orientation.

On 6 January 2006, the Regional Public Prosecutor in Viborg discontinued the investigation as he found no basis for concluding that the cartoons constituted a criminal offence. His reason is based on his finding that the article concerns a subject of public interest and, further, on Danish case law which extends editorial freedom to journalists when it comes to a subject of public interest. He stated that, in assessing what constitutes an offence, the right to freedom of speech must be taken into consideration. He stated that the right to freedom of speech must be exercised with the necessary respect for other human rights, including the right to protection against discrimination, insult and degradation, but no apparent violation of the law had occurred. In a new hearing, the Director of Public Prosecutors in Denmark agreed.

Danish Imams tour the Middle East

A group of Danish imams, dissatisfied with the reaction of the Danish Government and Jyllands-Posten created a forty-three-page document entitled, "Dossier about championing the prophet Muhammad peace be upon him."

The dossier consists of several letters from Muslim organisations explaining their case, citing the Jyllands-Posten cartoons but also the following causes of "pain and torment" for the authors:

- Pictures from another Danish newspaper, Weekendavisen, which they called "even more offending" (than the original twelve cartoons);

- Hate-mail pictures and letters that the dossier's authors alleged were sent to Muslims in Denmark, said to be indicative of the rejection of Muslims by the Danish;

- A televised interview discussing Islam with Dutch member of parliament and Islam critic Hirsi Ali, who had received the Freedom Prize "for her work to further freedom of speech and the rights of women" from the Danish Liberal Party represented by Anders Fogh Rasmussen.

Appended to the dossier are multiple clippings from Jyllands-Posten, multiple clippings from Weekendavisen, some clippings from Arabic-language papers, and three additional images.

The group of imams said that the three additional images were sent anonymously by mail to Muslims who were participating in an online debate on Jyllands-Posten, and were circulated to illustrate the atmosphere of Islamophobia in which they lived. On February 1 BBC World incorrectly reported that one of them had been published in Jyllands-Posten. This image was later found to be a wire-service photo of a contestant at a French pig-squealing contest. One of the other two additional images (a photo) portrayed a Muslim being mounted by a dog while praying, and the other (a cartoon) portrayed Muhammad as a demonic pedophile.

The group of imams set out for a tour of the Middle East to present their case to many influential religious and political leaders, and to ask for support. The dossier contains such statements as the following:

- We urge you [recipient of the letter or dossier] to — on the behalf of thousands of believing Muslims — to give us the opportunity of having a constructive contact with the press and particularly with the relevant decision makers, not briefly, but with a scientific methodology and a planned and long-term programme seeking to make views approach each other and remove misunderstandings between the two parties involved. Since we do not wish for Muslims to be accused of being backward and narrow, likewise we do not wish for Danes to be accused of ideological arrogance either. When this relationship is back on its track, the result will bring satisfaction, an underpinning of security and the stable relations, and a flourishing Denmark for all that live here.

- The faithful in their religion (Muslims) suffer under a number of circumstances, first and foremost the lack of official recognition of the Islamic faith. This has led to a lot of problems, especially the lack of right to build mosques [...]

- Even though they [the Danes] belong to the Christian faith, the secularizations have overcome them, and if you say that they are all infidels, then you are not wrong.

- We [Muslims] do not need lessons in democracy, but it is actually us, who through our deeds and speeches educate the whole world in democracy.

- This [Europe's] dictatorial way of using democracy is completely unacceptable.

The inclusion in the dossier of the cartoons from Weekendavisen was possibly a misunderstanding, as these were more likely intended as parodies of the pompousness of Jyllands-Posten's cartoons than as comments on the prophet in their own right. They consist of reproductions of works such as the Mona Lisa (caption: For centuries, a previously unknown society has known that this is a painting of the Prophet, and guarded this secret. The back page's anonymous artist is doing everything he can to reveal this secret in his contribution. He has since then been forced to go underground, fearing for the wrath of a crazy albino imam). This is an obvious parody of the Da Vinci Code.

At a 6 December 2005 summit of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, with many heads of state in attendance, the dossier was handed around on the sidelines first, and eventually an official communiqué was issued, demanding that the United Nations impose international sanctions upon Denmark.

Jyllands-Posten response

In response to protests from Muslim groups, Jyllands-Posten published two open letters on its website, each of them in a Danish and an Arabic version. The second letter, dated 30 January 2006, also has an English version:

In our opinion, the 12 drawings were sober. They were not intended to be offensive, nor were they at variance with Danish law, but they have indisputably offended many Muslims for which we apologize.

On February 26, the cartoonist who had drawn the bomb in turban picture, the most controversial of the twelve, explained:

There are interpretations of it [the drawing] that are incorrect. The general impression among Muslims is that it is about Islam as a whole. It is not. It is about certain fundamentalist aspects, that of course are not shared by everyone. But the fuel for the terrorists’ acts stem from interpretations of Islam. [...] if parts of a religion develop in a totalitarian and aggressive direction, then I think you have to protest. We did so under the other 'isms.

Reprinting in other newspapers

In 2005, the Muhammad cartoons controversy received only minor media attention outside of Denmark. Six of the cartoons were first reprinted by the Egyptian newspaper El Fagr on October 17, 2005, along with an article strongly denouncing them, but publication did not provoke any condemnations or other reactions from religious or government authorities. Between October 2005 and the end of January 2006, examples of the cartoons were reprinted in major European newspapers from the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia, Belgium and France. Very soon after, as protests grew, there were further re-publications around the globe, but primarily in continental Europe.

Notable for a lack of republication of the cartoons were major newspapers in the USA and the United Kingdom, where editorials covered the story without including them. Several newspapers were closed and editors fired or arrested for their decision or intention to re-publish the cartoons, including the shutting down of a 60 years old Malaysian newspaper permanently.

Economic and human costs

A consumer boycott was organised in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other Middle East countries. For weeks, numerous notable demonstrations and other protests against the cartoons took place worldwide. Rumours spread via SMS and word-of-mouth.On February 4, 2006, the Danish and Norwegian embassies in Syria were set ablaze, though with no injuries. In Beirut, the Danish Embassy was set on fire, leaving one protester dead. Altogether, at least 139 people were killed in protests, mainly in Nigeria, Libya, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Several death threats and reward offers for killing those responsible for the cartoons have been made, resulting in the cartoonists going into hiding.. Four ministers have resigned amidst the controversy, among them Roberto Calderoli and Laila Freivalds. In India, Haji Yaqoob Qureishi, a minister in Uttar Pradesh state government announced in February 2006 a cash reward of Rs 51 crore (roughly about US$11 million) for anyone who beheads the Danish cartoonist who caricatured Prophet Mohammad.

On September 9, 2006, it was announced that the Muslim boycott of Danish goods had reduced exports to the Muslim world by 15.5%, costing about €134 million. However, the Guardian newspaper in the UK also reported, "While Danish milk products were dumped in the Middle East, fervent rightwing [sic] Americans started buying Bang & Olufsen stereos and Lego. In the first quarter of this year Denmark’s exports to the US soared 17%."

Further police investigations

- The French/Algerian journalist Mohammed Sifaoui secretly filmed Ahmed Akkari, spokesman for the group of Danish Imams that toured the Middle East, in conversation with Sheikh Raed Hlayhel (head of the 2nd delegation), threatening to have MP Naser Khader bombed. Ahmad Abu Laban was also filmed, talking about a man who wants "to wreak absolute havoc" and "wants to join the fray and turn it into a Martyr operation right now." Akkari initially denied the remarks, then explained he was only joking. Both men were investigated, but no charges were brought.

- Police in Berlin overwhelm Amer Cheema, a student from Pakistan, as he enters the office building of Die Welt newspaper, armed with a large knife. Cheema admitted to trying to kill editor Roger Köppel for reprinting the Mohammad cartoons in the newspaper. On May 1, 2006, Cheema committed suicide in his prison cell. Cheema's family and Pakistani media claim he was tortured to death. 50,000 people attended Cheema's funeral near Lahore.

- Two suitcase bombs are discovered in trains near the German towns of Dortmund and Koblenz, undetonated due to an assembly error. Video footage from Cologne train station, where the bombs were put on the trains, led to the arrest of two Lebanese students in Germany, Youssef el-Hajdib and Jihad Hamad, and subsequently of three suspected co-conspirators in Lebanon. On 1 September 2006, Jörg Ziercke, head of the Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Police), reports that the suspects saw the Muhammad cartoons as an "assault by the West on Islam" and the "initial spark" for the attack, originally planned to coincide with the 2006 Football World Cup in Germany. One of the suspects, Youssef el-Hajdib, was arrested heading to Denmark. Police found the phone number of Abu Bashar, the leader of the Danish Imams' first cartoon-related delegation to the Middle East, in Hadjib's pockets.. Abu Bashar denies knowing al-Hajdib.

Anniversary flare-up

One year after the publication of the original cartoons, a video surfaced showing members of the Danish People's Party's youth wing engaged in a contest of drawing pictures that insult Muhammad, leading to renewed tension between the Islamic world and Denmark, with the OIC and many countries weighing in. The Danish government condemned the youths. Youths who were depicted on the video went into hiding after receiving death threats.

Two weeks into this episode, a Danish artists' group, " Defending Denmark", claimed responsibility for the video and said it had infiltrated the Danish People's Party Youth for 18 months "to document (their) extreme right wing associations".

Opinions and issues

Danish journalistic tradition

Freedom of speech was obtained in a new constitution in 1849, and defended vigorously ever since. It was suspended for the duration of the German occupation of Denmark in World War II. Freedom of expression is also protected by the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Newspapers are privately owned and independent from the government. Danish freedom of expression is quite far-reaching, even by Western standards, drawing official German protests about printing neo-nazi propaganda, and from Russia for "solidarity with terrorists." The organization Reporters Without Borders ranks Denmark at the top of its Worldwide Press Freedom Index for 2005.

Religion is often portrayed in ways that other societies consider illegal blasphemy. While Jyllands-Posten has published satirical cartoons depicting Christian figures, it did, in 2003, reject unsolicited surreal cartoons depicting Jesus, opening them to accusations of a double standard. In February 2006, Jyllands-Posten also refused to publish Holocaust denial cartoons offered by an Iranian newspaper. Six of the less controversial entries were later published by Dagbladet Information, after the editors consulted the main rabbi in Copenhagen, and three cartoons were in fact later reprinted in Jyllands-Posten. After the competition had finished, Jyllands-Posten also reprinted the winning and runner-up cartoons.

Muslim tradition

Aniconism

Owing to the traditions of aniconism in Islam, the majority of art concerning Muhammad is calligraphic in nature. The Qur'an condemns idolatry, but has no direct prohibitions of pictorial art as such. These are found in hadiths: " Ibn ‘Umar reported Allah’s Messenger ( pbuh) having said: Those who paint pictures would be punished on the Day of Resurrection and it would be said to them: Breathe soul into what you have created."

Views regarding pictorial representations within Muslim communities have varied. Shi'a Islam has been generally tolerant of pictorial representations of human figures, including Muhammad. Contemporary Sunni Islam generally forbids any pictorial representation of Muhammad, but has had periods allowing depictions of Muhammad's face covered with a veil or as a featureless void emanating light. A few contemporary interpretations of Islam, such as some adherents of Wahhabism and Salafism, are aniconistic and condemn pictorial representations of any kind. The Taliban, while in power in Afghanistan, banned television, photographs and images in newspapers and destroyed paintings including frescoes in the vicinity of the Buddhas of Bamyan.

Prohibition to insult Muhammad

In Muslim societies, to insult the Islamic prophet Muhammad is one of the most serious crimes anyone could commit. Some interpretations of the Shariah, in particular the relatively fringe Salafi group, state that any insult to Muhammad warrants death.

The Organization of the Islamic Conference has on the other hand denounced calls for the death of the Danish cartoonist. OIC's Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu told journalists in Islamabad:

This is not a joke to go and say kill this and that. This is a very serious matter and nobody has the authority to issue a ruling to kill people.

Associating Islam with terrorism

Many Muslims have explained their anti-cartoon stance as against insulting pictures and not so much as against pictures in general. According to the BBC:

It is the satirical intent of the cartoonists and the association of the Prophet with terrorism, that is so offensive to the vast majority of Muslims.

Why is the insult so deeply felt by some Muslims? Of course, there is the prohibition on images of Muhammad. But one cartoon, showing the Prophet wearing a turban shaped as a bomb with a burning fuse, extends the caricature of Muslims as terrorists to Muhammad. In this image, Muslims see a depiction of Islam, its prophet and Muslims in general as terrorists. This will certainly play into a widespread perception among Muslims across the world that many in the West harbour a hostility towards – or fear of – Islam and Muslims.

According to some interpretations, the bomb in turban cartoon is also violent - soon the bomb will explode the head of the prophet, and this is presented as humorous.

Islamism and xenophobia

Fundamentalist Islam is now seen to be a problem in Europe recently, while disillusionment with multiculturalism is on the rise in Denmark. This is further fuelled by Mullah Krekar stating that "the number of Muslims is expanding like mosquitoes." The UNCHR Special Rapporteur, on the other hand, saw xenophobia and racism in Europe as the root of the crisis. Denmark has been singled out in this regard.

Allegations of "agendas"

The West's or Zionist agendas

Some commentators see the publications of the cartoons and the riots that took place in response, as part of a coordinated effort to show Muslims and Islam in a bad light, thus influencing public opinion in the West to support further military intervention in the Middle East.

Among others, Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei blamed a "Zionist conspiracy" for the row over the cartoons. The Palestinian envoy to Washington said the Likud party concocted distribution of Muhammad caricatures worldwide in a bid to create a clash between the West and the Muslim world. The criminalization of denial of the Holocaust in parts of Europe received renewed interest, raising concerns over freedom of speech being asserted selectively.

Islamist or Mideast regime agendas

Other commentators see Islamists jockeying for influence both in Europe and the Islamic Ummah, who tried (unsuccessfully) to widen the split between the USA and Europe, and simultaneously bridge the split between the Sunnis and the Shia.

Regimes in the Middle East have been accused of taking advantage of the crisis, and adding to it, in order to demonstrate their Islamic credentials, distracting from their failures by setting up an external enemy, and "(using) the cartoons [...] as a way of showing that the expansion of freedom and democracy in their countries would lead inevitably to the denigration of Islam." Mahmoud Ahmadinejad announced a Holocaust Conference, supported by the OIC, to uncover what he called the "myth" used to justify the creation of Israel. Ahmadinejad started voicing doubt about the veracity of the holocaust at the same OIC conference in Mecca that served to spread the Akkari-Laban dossier to leaders of the Muslim world.

Political correctness

What started with the problem of a Danish author trying to find an illustrator for his book, became an international crisis. Many governments and international organizations have issued statements.

Critics of political correctness see the cartoon crisis as a sign that attempts at judicial codification of such concepts as respect, tolerance and offense have backfired on their advocates, "leaving them without a leg to stand on" and in retreat again:

The issue will almost certainly lead to a revisiting of the lamentable laws against "hate speech" in Europe, and with any luck to a debate on whether these laws are more likely to destroy public harmony than encourage it. Muslim activists are finding out why getting into a negative-publicity fight is as inadvisable as wrestling with a pig: You get dirty and the pig enjoys it.