Jonathan Wild

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Historical figures

Jonathan Wild (c. 1683– May 24, 1725) was perhaps the most famous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them. He invented a scheme which allowed him to run one of the most successful gangs of thieves of the era, all the while appearing to be the nation's leading policeman. He manipulated the press and the nation's fears to become the most loved public figure of the 1720s; this love turned to hatred when his villainy was exposed. After his death, he became a symbol of corruption and hypocrisy.

Life

Wild was born in Wolverhampton in 1683 to a poor family. After serving as an apprentice to a buckle-maker, he worked as a servant and came to London in 1704. After being dismissed by his master, he returned to Wolverhampton, where he was arrested for debt. During this time in debtor's prison, he became popular and received "the liberty of the gate" (meaning being allowed out at night to aid in the arrest of thieves). There, he met one Mary Milliner (or Mary Mollineaux), a prostitute who began to teach Wild criminal ways and, according to Daniel Defoe, "brought him into her own gang, whether of thieves or whores, or of both, is not much material." With these new methods of raising money, Wild was able to pay his way out of prison.

Upon release, Wild began to live with Mary Milliner as her husband, despite both of them having prior marriages and — in Wild's case — a child. Wild apparently served as Milliner's tough when she went night-walking. Soon Wild was thoroughly acquainted with the underworld, both with its methods and its inhabitants, and he parted with Milliner. At some point during this period, Milliner had begun to act as something of a madam to other prostitutes, and Wild as a fence, or receiver of stolen goods.

Wild began, slowly at first, to dispose of stolen goods and to pay bribes to get thieves out of jail.

Wild's public career

Wild's method of illegally amassing riches while appearing to be on the side of the law was ingenious. He ran a gang of thieves, kept the stolen goods, and waited for the crime and theft to be announced in the newspapers. At this point, he would claim that his "thief taking agents" (police) had "found" the stolen merchandise, and he would return it to its rightful owners for a reward (to cover the expenses of running his agents). In some cases, if the stolen items or circumstances allowed for blackmail, he did not wait for the theft to be announced. As well as "recovering" these stolen goods, he would offer the police aid in finding the thieves. The thieves that Wild would help to "discover", however, were rivals or members of his own gang who had refused to cooperate with his taking the majority of the money.

Crime had risen dramatically in London between 1680 and 1720, and in 1712 Charles Hitchen, Wild's forerunner and future rival as thief-taker, said that he personally knew 2,000 people in London who made their living solely by theft. Hitchen, the City's top policeman, would himself end at the pillory, as it appeared later that he accepted bribes to let thieves out of jail and to selectively arrest criminals and coerce sexual services from molly houses; his testimony was in connection with his criminal conspiracy investigation by the London Board of Aldermen. (Hitchen's downfall would occur when he was arrested for sodomy, rather than corruption.)

The advent of daily newspapers had led to a rising interest in crime and criminals. As the papers reported notable crimes and ingenious attacks, the public worried more and more about property crime and grew more and more interested in the issues of criminals and policing. London depended entirely upon localized policing and had no city-wide police force. Unease with crime was at a feverish high. The public was eager to embrace both colourful criminals (e.g. Jack Sheppard and the entirely upper-class gang called the " Mohocks" in 1712) and valiant crime-fighters. The city's population had more than doubled, and there was no effective means of controlling crime. London saw a rise not only in thievery, but in organized crime during the period.

"Thief-Taker General"

Wild would be recognizable today as the prototype of a "media don", courting the public while simultaneously ruthlessly administering a crime empire like John Gotti.

Wild's ability to hold his gang together, and indeed the majority of his scheme, relied upon the fear of theft and the nation's reaction to theft. The crime of selling stolen goods became increasingly dangerous in the period from 1700 to 1720. Low-level thieves ran a great risk in fencing their goods. Wild avoided this danger and exploited it simultaneously by having his gang steal (either through pick-pocketing or, more often, mugging) and then by "recovering" the goods. He never sold the goods back, explicitly, nor ever pretended that they were not stolen. He claimed at all times that he found the goods by policing and avowed hatred of thieves. That very penalty for selling stolen goods, however, allowed Wild to control his gang very effectively, for he could turn in any of his thieves to the authorities at any time. By giving the goods to him for a cut of the profits, Wild's thieves were selling stolen goods. If they did not give their take to him, Wild would simply apprehend them as thieves. However, what Wild chiefly did was use his thieves and ruffians to "apprehend" rival gangs.

Jonathan Wild was not the first thief-taker who was actually a thief himself. Charles Hitchen had used his position as City Marshal to practice extortion. He had pressured brothels and pickpockets to pay him off or give him the stolen goods for return to their owners since purchasing the position in 1712. When Hitchen was suspended from his duties for corruption in that year, he engaged Jonathan Wild to keep his business of extortion going in his absence. Hitchen was re-instated in 1714 and found that Wild was now a rival, and one of Wild's first bits of gang warfare was to eliminate as many of the thieves in Hitchen's control as he could. In 1718, Hitchen attempted to expose Wild with his A True Discovery of the Conduct of Receivers and Thief-Takers in and about the City of London. There he named Wild as a manager and source of crime. Wild replied with An Answer to a Late Insolent Libel and there explained that Hitchen was a homosexual who visited " molly houses." Hitchen attempted to further combat Wild with a pamphlet entitled The Regulator, which was his characterization of Wild, but Hitchen's prior suspensions from duties and the shocking charge of homosexuality virtually eliminated him as a threat to Wild.

Wild held a virtual monopoly on crime in London. He kept records of all thieves in his employ, and when they had outlived their usefulness, Wild sold them to the gallows for the £40 reward. Wild's system inspired a fake or folk etymology of the phrase " double cross". He kept the names of the thieves in his employ in a ledger. It is alleged that, when a thief vexed Wild in some way, he put a cross by the thief's name; a second cross condemned the man to be sold to the Crown for hanging. Note that the noun "double cross" did not enter English usage until 1834.

In public, Wild presented a heroic face. He was the man who returned stolen goods. He was the man who caught criminals. In 1718, Wild called himself "Thief Taker General of Great Britain and Ireland". By his testimony, over sixty thieves were sent to the gallows. His "finding" of lost merchandise was private, but his efforts at finding thieves were public. Wild's office in the Old Bailey was a busy spot. Victims of crime would come by, even before announcing their losses, and discover that Wild's agents had "found" the missing items, and Wild would offer to help find the criminals for an extra fee. However, while fictional treatments made use of the device, it is not known whether or not Wild ever actually turned in one of his own gang for a private fee.

In 1720, Wild's fame was such that the Privy Council consulted with him on methods of controlling crime. Wild's recommendation was, unsurprisingly, that the rewards for evidence against thieves be raised. Indeed, the reward for capturing a thief went from forty pounds to one hundred and forty pounds within the year. This amounted to a significant pay increase for Wild.

There is some evidence that Wild was favoured, or at least ignored, by the Whig politicians and opposed by the Tory politicians. In 1718, a Tory group had succeeded in having the laws against receiving stolen property tightened, primarily with Wild's activities in mind. Ironically, this strengthened Wild's hand, rather than weakening it, for it made it more difficult for thieves to fence their goods except through Wild.

Wild's battles with thieves made excellent press. Wild himself would approach the papers with accounts of his derring-do, and the papers passed these on to a concerned public. Thus, in July to August of 1724, the papers carried accounts of Wild's heroic efforts in collecting twenty-one members of the Carrick Gang (with an £800 reward - approximately £25,000 in the year 2000). When one of the members of the gang was released, Wild pursued him and had him arrested on "further information". To the public, this seemed like a relentless defense of order. In reality, it was a gang warfare disguised as national service.

When Wild solicited for a finder's fee, he usually held all the power in the transaction. For example, David Nokes quotes (based on Howson) the following advertisement from the Daily Post in 1724 in his edition of Henry Fielding's Jonathan Wild:

- "Lost, the 1st of October, a black shagreen Pocket-Book, edged with

- Silver, with some Notes of Hand. The said Book was lost in the

- Strand, near Fountain Tavern, about 7 or 8 o'clock at Night. If

- any Person will bring aforementioned Book to Mr Jonathan Wild,

- in the Old Bailey, he shall have a Guinea reward."

- Silver, with some Notes of Hand. The said Book was lost in the

The advert is extortion. The "notes of hand" (agreements of debt) mean signatures, so Wild already knows the name of the book's owner. Furthermore, Wild tells the owner through the ad that he knows what its owner was doing at the time, since the Fountain Tavern was a brothel. The real purpose of the ad is to threaten the notebook's owner with announcing his visit to a bordello, either to the debtors or the public, and it even names a price for silence (a guinea, or one pound and one shilling).

The Jack Sheppard struggle and downfall

By 1724, London political life was experiencing a crisis of public confidence. In 1720, the South Sea Bubble had burst, and the public was growing restive about corruption. Authority figures were beginning to be viewed with scepticism.

In February 1724, the most famous housebreaker of the era, Jack Sheppard, was apprehended by Wild. Sheppard had worked with Wild in the past, though he had struck out on his own. Consequently, as with other arrests, Wild's interests in saving the public from Sheppard were personal.

Sheppard was imprisoned in St Giles' Roundhouse and immediately escaped. In May, Wild again had Sheppard arrested, and this time he was put in the New Prison. Sheppard escaped in less than a week. In July, Wild had Sheppard arrested for a third time. He was tried, convicted, and put in the condemned hold of Newgate Prison. On the night that the death warrant arrived, August 30, Sheppard escaped. By this point, Sheppard was a working class hero (being a cockney, non-violent, and handsome). On September 11, Wild's men caught him for a fourth time, and Sheppard was placed in the most secure room of Newgate. Further, Sheppard was put in shackles and chained to the floor. On September 16, Sheppard escaped yet again. Sheppard had broken the chains, padlocks, and six iron-barred doors. This escape astonished everyone, and Daniel Defoe, working as a journalist, wrote an account. In late October, Wild found Sheppard for a fifth and final time and had him arrested. This time, Sheppard was placed in the centre of Newgate, where he could be observed at all times, and loaded with three hundred pounds of iron weights. He was so celebrated that the gaolers charged high society visitors to see him, and James Thornhill painted his portrait.

Sheppard was hanged at Tyburn on November 16, 1724.

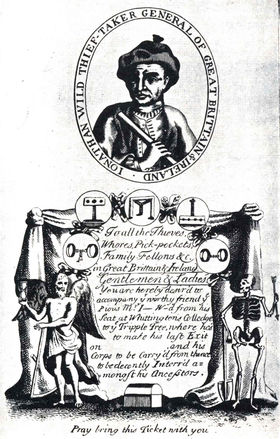

During the pursuit of Sheppard, Wild appeared as much to disadvantage in the press as Sheppard did to advantage. Wild was now despised. When, in February 1725, Wild used violence to perform a jail break for one of his gang members, he was arrested. He was placed in Newgate, where he continued to attempt to run his business. In the illustration from the True Effigy, above, Wild is pictured in Newgate, still with notebook in hand to account for goods coming in and going out of his office. Evidence was presented against Wild for the violent jailbreak and for having stolen jewels during the previous August's installation of Knights of the Garter.

The public's mood had shifted; they supported the average man and resented authority figures. Wild's trial occurred at the same time as that of the Lord Chancellor, Lord Thomas Parker, Earl of Macclesfield, for taking £100,000 in bribes. With the changing tide, it appeared at last to Wild's gang that their leader would not escape, and they began to come forward. Slowly, gang members began to turn evidence on him, until all of his activities, including his grand scheme of running and then hanging thieves, became known. Additionally, evidence was offered as to Wild's frequent bribery of public officers.

When Wild went to the gallows at Tyburn on May 24, 1725, Daniel Defoe said that the crowd was far larger than any they had seen before and that, instead of any celebration or commiseration with the condemned,

- "wherever he came, there was nothing but hollowing and huzzas,

- as if it had been upon a triumph."

- as if it had been upon a triumph."

Wild's hanging was a great event, and tickets were sold in advance for the best vantage points (see the reproduction of the gallows ticket). Even in a year with a great many macabre spectacles, Wild drew an especially large and boisterous crowd. In the 18th century, autopsies and dissections were performed on the most notorious criminals, and consequently Wild's body was sold to the Royal College of Surgeons for dissection. His skeleton remains on public display in the Royal College's Hunterian Museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields.

Literary treatments

Jonathan Wild is famous today not so much for setting the example for organized crime as for the uses satirists made of his story.

When Wild was hanged, the papers were filled with accounts of his life, collections of his sayings, farewell speeches, and the like. Daniel Defoe wrote one narrative for Applebee's Journal in May and then had published True and Genuine Account of the Life and Actions of the Late Jonathan Wild in June 1725. This work competed with another that claimed to have excerpts from Wild's diaries. The illustration above is from the frontispiece to the "True Effigy of Mr. Jonathan Wild," a companion piece to one of the pamphlets purporting to offer the thief-taker's biography.

Criminal biography was already an existing genre. These works were popular then, as now, because they could offer a touching account of need, a fall from innocence, sex, violence, and then repentance or a tearful end. Public fascination with the dark side of human nature, and with the causes of evil, has never waned, and the market for mass produced accounts was large.

By 1701 there had been a Lives of the Gamesters (often appended to Charles Cotton's The Compleat Gamester), about notorious gamblers. In 1714 Captain Alexander Smith had written the best-selling Complete Lives of the Most Notorious Highwaymen. Defoe himself was no stranger to this market: his Moll Flanders was published in 1722. Further, he had, by 1725, written both a History and a Narrative of the life of Jack Sheppard (see above). Moll Flanders may be based on the life of one Moll King, who lived with Mary Mollineaux/Milliner, Wild's first mistress.

What differs about the case of Jonathan Wild is that it was not simply a crime story. Parallels between Wild and Robert Walpole were instantly drawn, especially by the Tory authors of the day. Mist's Weekly Journal (one of the more rough-speaking Tory journals) drew a parallel between the figures in May 1725, when the hanging was still in the news.

The parallel is most important for John Gay's The Beggar's Opera in 1728. The main story of the Beggar's Opera focuses on the episodes between Wild and Sheppard. In the opera, the character of Peachum stands in for Wild (who stands in for Walpole), while the figure of Macheath stands in for Sheppard (who stands in for Wild and/or the chief officers of the South Sea Company). Robert Walpole himself saw and enjoyed Beggar's Opera without realizing that he was its intended target. Once he did realize it, he banned the sequel opera, Polly, without staging. This prompted Gay to write to a friend, "For writing in the cause of virtue and against the fashionable vices, I have become the most hated man in England almost."

In 1742, Robert Walpole lost his position of power in the House of Commons. He was created a peer and moved to the House of Lords, from where he still directed the Whig majority in Commons for years. In 1743, Henry Fielding's The History of the Life of the Late Mr Jonathan Wild the Great appeared in the third volume of Miscellanies.

Fielding is merciless in his attack on Walpole. In his work, Wild stands in for Walpole directly, and, in particular, he invokes the Walpolean language of the "Great Man". Walpole had come to be described by both the Whig and then, satirically, by the Tory political writers as the "Great Man", and Fielding has his Wild constantly striving, with stupid violence, to be "Great". "Greatness," according to Fielding, is only attained by mounting to the top stair (of the gallows). Fielding's satire also consistently attacks the Whig party by having Wild choose, among all the thieves cant terms (several lexicons of which were printed with the Lives of Wild in 1725), " prig" to refer to the profession of burglary. Fielding suggests that Wild becoming a Great Prig was the same as Walpole becoming a Great Whig: theft and the Whig party were never so directly linked.

The figures of Peachum and Macheath were picked up by Bertolt Brecht for his updating of Gay's opera as The Threepenny Opera. The Sheppard character, Macheath, is the "hero" of the song Mack the Knife.

More recently, Jonathan Wild appeared as a character in the David Liss novel A Conspiracy of Paper, ISBN 0-8041-1912-0. Jonathan Wild is also the title character in the 2005–2006 Phantom stories "Jonathan Wild: King of Thieves" and "Jonathan Wild: Double Cross".